A Lost Opportunity: Glendale

In late June 1862, Robert E. Lee Struck George McClellan’s right flank at Mechanicsville. This attack, plus reports that Stonewall Jackson’s valley army was approaching on his right, caused McClellan to change his base from White House Landing on the Pamunkey to the security of the James River. He needed time, and ordered Fitz John Porter to hold put another day north of the Chickahominy River. Following orders, Porter bought precious time for the Army of the Potomac. The most famous of the Seven Days’ Battles, Gaines’s Mill, was the result. Porter held out until nightfall, when he was finally driven across the river.

The next day, June 28th, Lee spent in determining where McClellan would go. Would he retreat down the Peninsula, would he attack Richmond, or would he move to the James? By nightfall he knew that McClellan had made the latter choice. His army retreated across the Peninsula, basically on one road, right across Lee’s lines. The Confederates had a series of roads, like the spokes of a wheel, pointing at the enemy retreat. Lee know that the South could not win a protracted war, as it simply didn’t have the population or manufacturing capacity enjoyed by the North. He needed to either crush the enemy’s army, or cause the North to abandon the war. Now Lee had the opportunity he needed, and it might not come again. He wanted to take advantage of McClellan’s vulnerable situation and strike a blow that would seriously damage, if not destroy the Army of the Potomac. What would come next was the most important, if not the most famous, of the Seven Days’ battles.

As McClellan retreated, his army moved south until it reached an intersection known locally as Riddell’s Shop (today called Glendale). Here it would turn, march over Malvern Hill, and then on to the safety of its gunboats on the James. The key was Glendale. Lee decided he would cut the enemy in half at that road juncture, then destroy it in detail.

Lee’s army was new to him. He had taken command only a month earlier, and was not familiar with most of his commanders His staff was small and newly formed, and the terrain could be challenging for communications. To make matters worse, and almost unbelievably, the Confederates did not have good maps of the area, only a few miles from their capital. Their advantage was that they had 72,000 men that they could launch at the enemy.

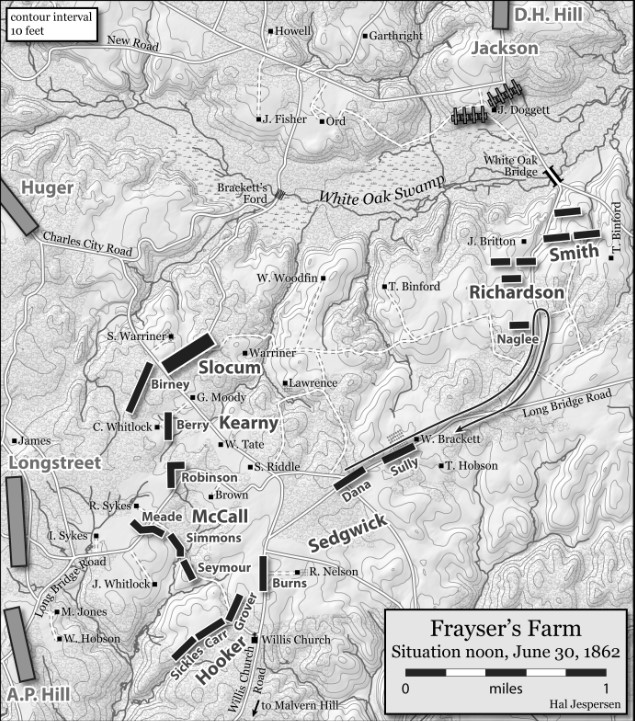

Lee would send Benjamin Huger, James Longstreet and A. P. Hill, with a combined 29,000 men, to strike at Glendale. Huger would move down Charles City Road. The others would come up Long Bridge Road. Theophilus Holmes and his small division would march down New Market Road (today’s Route 5). He would harass the enemy retreat across Malvern Hill, and possibly seize that point. The hammer would be Stonewall Jackson. He had his army, plus D. H. Hill’s division, some 25,000 men. They would attack the enemy’s rear at White Oak Swamp. Together with the force that moved against Glendale, their overwhelming power would crush any Yankees north of Glendale, at least half of the enemy army. As a bonus, McClellan would not be on the battlefield; he would be scouting for a new position on the river. No one was left in charge, and the Federal units set up a fishhook-type defense. Units were scattered… parts of divisions were mixed up with other units.

Lee’s plan began to unravel almost immediately. Huger moved down Charles City Road, but the Federals were cutting down trees to block his way. Rather than send a force to stop this, he spent his time cutting up and removing the trees, and considering building a new road. He was to start the attack, there was no time for road construction! His contribution for the day was an exchange of artillery fire with the enemy. 10,000 Confederates were now out of the fight.

Theophilus Holmes didn’t fare much better. He was slow to move, and the result was that

Union troops under Porter established a position with artillery on New Market Heights. Gouverneur Warren’s brigade blocked the New Market Road, and Federal gunboats fired on Holmes’ men from the river. Lee rode down and witnessed the lack of progress and ordered John Bankhead Magruder to bring his division as reinforcements. He arrived too late to do any good, and another 18,000 Confederates were out of the attack.

What of Jackson? With 25,000 men and his reputation for decisive action, things were still promising. Unfortunately, this would be Stonewall’s worst day. He never aggressively pursued an attack across White Oak Swamp. The enemy in his front was strong, but scouts found a few ways across and beyond the Federals’ flank. Wade Hampton even built a bridge. Jackson was not himself… modern historians suggest that he was exhausted. He fell asleep eating, arose, and then went to bed. His army would not attack that day. Lee was down another 25,000 men!

It was left to Longstreet and A. P. Hill. Longstreet was ordered to advance, and he did, but owing to the heavily wooded terrain near Glendale, his brigades attacked in a disjointed fashion. The Pennsylvania Reserves fought back doggedly. Lack of action by Huger and Jackson allowed the Federals to pull troops from those sectors, and they held off the Confederate assault. Lee’s last chance was A. P. Hill. His men moved forward, but could not reach Willis Church Road before darkness fell. That night the Federals pulled back to Malvern Hill, where disaster awaited Lee’s army the next day.

It seems almost unbelievable that the Confederate attack could have failed, but everything that could have gone wrong certainly did. Communications were poor, the terrain was difficult, and some of Lee’s commanders were simply not up to the job. Magruder, Huger and Holmes would soon be sent away. While Jackson’s performance was non-existent, Lee had observed the Valley campaign and knew his potential. The enemy was driven from Richmond, but the Confederates had missed an opportunity that might not come again. To Lee’s chagrin, the war would go on.

Thanks for this nice summary. The Battle of Glendale published by Arcadia Press is strongly recommended as the best modern monograph on this battle. A significant part of the battlefield has been saved by the Battlefield Trust. The ECW book on the Seven Days, Richmond Shall Not Be Given Up, also is recommended with its tour guide.

Any particular reason why the article focuses entirely from the CS perspective? I think the Yankees had something to do with Lee’s inability to cut off McClellan’s retreat at Glendale….Kudos to Sumner, Hooker, Sedgwick, Simmons, Meade, Robinson, Caldwell, to name a few, for showing initiative and their brave defense of the crossroads.

Read the title of the article Todd. It’s about what the Confederates did that day and not what Yankees did that day. Come on man.

I note that you didn’t mention a certain name on the Union side – I wonder where he was.

Lyle, exactly my point. It was a “lost opportunity” for the Confederates because in part of the Federal defense. Not because the Confederates were slightly less than perfect that day. Come on man!

The evidence from that day suggests otherwise Todd. We’ll never know how the Federals would have handled the attack that Lee envisioned, because of what the Confederates didn’t do and not what the Federal did, which is the whole point of the article.

SLIGHTLY less than perfect that day? Perhaps damned by faint praise.. The question abut the location and condition of “stonewal[ seems to be needing a more thorough medical review..l am trying to write something about this subject but information seems hard to come by. My big question for the experts is where, exactly, where was stonewall during Glendale.

Snoozing north of White Oak Swamp.

There would certainly be many, MANY, more ‘lost opportunities’ for both sides.

Yes, but some things don’t seem to add up. The Chickahominy Escarpment is variable in height and steepness from the RR bridgeto the white oak swamp Bridge at what would become Elko There is a triangle of roads connecting these points with Bottoms Bridge on the east Boar Swanp on the west and White oak swamp on the south (below Glendale.). The road from Bottoms Bridge to White Oak Bridge is very steep in places and would not be easy to move an army across it. The Old Williamsburg road met this road at a T just above Bottoms bridge, where you could go up and down the road by choice. The road connecting White Oak bridge to Boar swamp and Savages station was in use by the retreating Federals. The problem is that the actual “road“ from Bottoms bridge to White Oak is terribly steep, with washouts and an intermediate small bridge in it . Perhaps Stonewall got reports that the White Oak Road was very difficult and poor and decided he could mot squeeze his army thru it. At this point Geology was his enemy. I have driven this road many times and it is difficult even paved. Perhaps a thread worth following.

The idea that McClellan intended to continue from Glendale is wrong. McClellan intended to remain there, resupply his army from Carter’s and Haxall’s Landings, and counterattack once he’d resupplied. The quartermasters set up landing points and depots at those two places (which they wouldn’t do if the intent was Harrison’s), only for the Navy to state they couldn’t protect transports that far upriver. The Navy wanted for the army to retreat all the way to Dancing Point (i.e. the mouth of the Chickahominy).

Tactically, the reason for the withdrawal from the Glendale position is that Baldy Smith suffered a complete mental breakdown, and marched his division away from the White Oak towards Charles City without telling anyone, and Franklin followed him.

The rebels never intended to attack the crossroads, at least not on the 30th. Like the attacks at Malvern Hill the following day, it was an unco-ordinated snowballing attack. Jenkins’ unordered charge at about 1645 caused a shocked Longstreet to order a general attack at 1700. Since no-one expects to make an attack that day, the response is ragged; only Kemper advanced promptly. It was about 2 hours after Jenkins’ first charge that Pryor and Featherstone advanced.

The reason for the disruption was simple – no-one expected there to be a battle. Longstreet’s ill-considered order for a general attack failed to account for the fact that most of his men had gone into routine and were busy cooking their dinners. Hence he lost 3 casualties for every two inflicted (ca. 4,349 received vs ca. 2,813 inflicted) to gain 100 yards of ground. The guns were not in rebel possession at the end of the battle, but rather between the lines. Baldy Smith’s psychosis covers up Longstreet’s mistake, because Jackson crossed the White Oak in the dark, and unzipped the whole Federal position.