Forgetting Nashville

Among the twenty-five bloodiest battles of the American Civil War, Nashville—fought December 15-16, 1864—stands as among the most “forgotten.” Only two major works, by Stanley F. Horn and James Lee McDonough, have chronicled the engagement. The reasons for this are multi-faceted, and do much to explain the complications of Civil War memory and historiography.

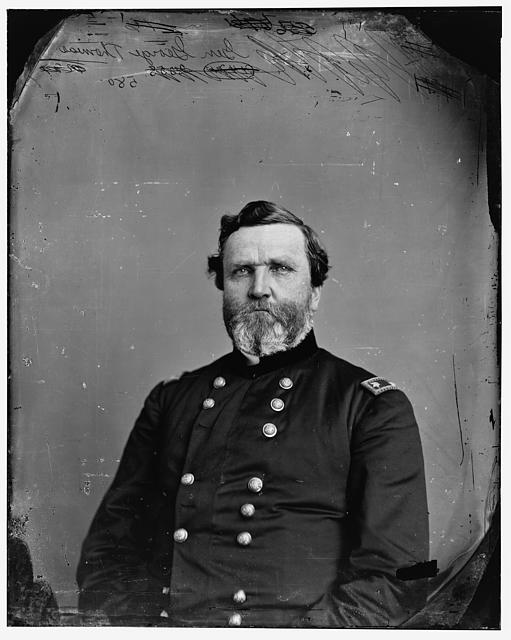

On the surface it seems clear enough why Nashville is forgotten. John Bell Hood’s Army of Tennessee lost the Tennessee campaign at Spring Hill, while the carnage at Franklin ended his last slim chances of victory. Nashville comes off as a kind of bloody afterthought, a ludicrous attempt to save a cause that was long lost. The battle itself was not close. In two days Hood’s men were pounded by a polyglot army led by George Thomas, the best tactician in either army. Although two Federal attacks failed, the other two were a stunning success. Few Confederates would want to remember or celebrate that day. Franklin was a defeat, but the attempt was an example of valor. Of Nashville, Hood once wrote “I beheld for the first and only time a Confederate army abandon the field in confusion.”

Nashville also came after Abraham Lincoln had been reelected, William Tecumseh Sherman was at the gates of Savannah, and Philip Sheridan had burned the Shenandoah Valley. The war was decided, and Nashville seemed like an afterthought. A tragic afterthought, but an afterthought all the same.

Lastly, there is no park at Nashville, and preservation there has been limited. The people of Nashville were lukewarm about a 1910 move to create such a park. Some of it was due to the quality of the land, which is today mostly dotted by suburban housing. They also had no desire to see markers of a hopeless battle, particularly when the battlefields of Shiloh and Chickamauga were covered in monuments to a side they saw as conquerors. With no park to draw in veterans and their descendants and tourists, the battle eroded into the mists of time, known only by a few markers and the impressive Battle of Nashville Monument Park. Nashville, today a magnet for out of town millennials entranced by its music scene, hardly recalls or cares that thousands fought and died over much of the current city. Given the current animus towards Civil War history not in line with the Just Cause mythology, there is no hope this will reverse course. At this point, the Battlefield Trust had better get serious about taking over Nashville sites maintained by the Sons of Confederate Veterans, an organization that appears to be in terminal decline.

The above reasons have some merit, but they do not explain just how thoroughly the battle has been forgotten. To understand that one has to consider how both sides viewed the war and the competing mythologies they crafted. Neither the Lost Cause nor the Just Cause had any major reasons to recall the fighting.

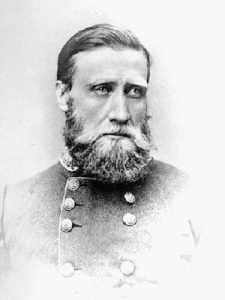

The Lost Cause was obsessed with Southern valor and the generalship of Virginia’s “holy trinity” of Robert E. Lee, James “Jeb” Stuart, and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. None of those three men were present. Hood made for an imperfect Lost Cause hero. He was portrayed as something of a tragic figure, but one tainted by his bitter memoirs, machinations against Joseph E. Johnston, and hopeless battles where he was unfairly cast as an unfeeling monster. He also took a neutral stance during Reconstruction, ignoring politics to concentrate on family, business, and aid to crippled veterans. Other Lost Cause fixtures were absent. Nathan Bedford Forrest was away raiding and Patrick Cleburne was dead. The only comparable popular figure at the battle was Benjamin Cheatham, but he was celebrated in Tennessee but not elsewhere.

The Confederates ended up fleeing from Nashville in disorder. Sam Watkins of the 1st Tennessee wrote that attempts to rally the men “was like trying to stop the current of Duck river with a fish net.” If one wanted to play up Southern fortitude, Nashville certainly was not it outside of few moments such as the stand by William Shy on Compton’s Hill. Where the Rebels did well was in repelling attacks made by the USCT on the right, but the racial aspect of this fighting and its bitterness was something Lost Cause peddlers tried to downplay in order to gain more sympathy in the North, particularly among Union veterans.

The Just Cause, which is the current ascendant memory of the war, would seem to have much to be proud of. The battle featured USCT regiments at their best on December 16. A Rebel army was routed, with Union troops showing great pluck. In Minnesota the battle was recalled with a magnificent painting and two future governors, Lucius F. Hubbard and William R. Marshall, led brigades in the attack up Compton’s Hill. The battle was crucial in determining the fall of the Confederacy, for in the words of Colonel Henry Stone of Thomas’ staff “…the whole structure of the rebellion in the Southwest, with all its possibilities, was utterly overthrown.”

Yet, the battle did feature two inconvenient aspects that complicate the Just Cause narrative. The USCT performance, at least on December 15, was poor. Although their attack was over rough and poorly scouted ground, they melted away fast under fire, as did nearby white troops. Their actions did not impress anyone. The popular and repeated narrative of black soldiers fighting an impossible battle but winning respect from white soldiers does not apply to their December 15 efforts. However, it does apply to December 16, so it could be argued the two cancel each out. Either way, it is not the main reason the battle was forgotten in the North.

The Just Cause’s holy trinity, at least as far as the army goes, is Sherman, Sheridan, and most of all Ulysses S. Grant. None of them were at Nashville. To make it worse, Thomas was there, he was victorious, and Grant did not like him. One should not however say that Grant despised Thomas. Grant reserved that for William Rosecrans and Gordon Granger.

The Grant of the Just Cause mythology is a military genius of modest manners, and commendable politics. None of these hold up fully under scrutiny. While Grant was talented, particularly at logistics, strategy, and operational maneuver, he was an average tactician who lacked battlefield charisma and could be a very sloppy administrator. He lost a lot of battles, and he nearly cost Lincoln the 1864 election. He was a talented commander, but not a genius on par with Marlborough, Frederick II, or Maurice de Saxe. His politics were marred by corruption and the sad fact that by 1875 he was abandoning the Freedmen while preparing for a land grab aimed at the Sioux. I do not bring up the above to say he was incompetent, evil, or “the butcher” of Lost Cause mythology, only that he was complicated. I personally find hero worship, whether it is directed at Grant, Lincoln, Lee, or even Horatio Nelson and Harriet Tubman, abhorrent since it strips away the humanity to create a symbol that always withers under a careful microscope.

Grant did some good as a politician and he was a talented general, but on one point I do find him reprehensible. He was man who favored friends and punished enemies, and he did the later with palatable malice. That itself is not new. Just read about how Ernest J. King ran the navy during World War II. However, King was blunt, while Grant was more indirect and hid behind a false modesty. Nothing shows this more than Nashville. He wanted Thomas to attack right away despite bad weather and his cavalry not being ready. Unwilling to remove a beloved officer, he wanted Henry Halleck to do it, until he resolved on the act. To his favorites, Grant showed consideration. He did not rush Sheridan into the Shenandoah Valley, and he gave Sherman latitude in 1864. With Thomas, who was a proven battle commander, he barraged him with impossible orders and plotted his fall. After the victory, Grant falsely claimed that Thomas was slow in his pursuit and he opposed Thomas’ promotion to major general, relenting only when it was clear that Lincoln and Edwin Stanton were intent on it. To study Nashville is to see the less savory aspects of Grant’s personality and military thinking (he somehow thought Hood was getting stronger), just as studying Vicksburg or Appomattox shows Grant at his best. Yet, one must reckon honestly with both to avoid the current vogue of Grant hagiography.

If Grant, Sherman, or Sheridan had been in command at Nashville, I have no doubt it would have been covered in at least ten books in the last sixty years, each discussing the Union victory as a work of genius by a military commander who set the template for “modern war.” To avoid the tropes of Civil War history, and the traps of causes Lost and Just, we must consider things we do not like about the people we cover, study battles that do not feature the cast of Ken Burns’ The Civil War, and most of all place the Civil War in the wider context of its era of warfare.

At least Cheatham got a county named after him.

As did Hood!

Interesting article. Thank you. I suppose Nashville was/is anticlimactic to many after the disaster at Franklin. I feel Rosecrans deserves some share of the blame in the running 20-year animosity between him and Grant. Evan Jones did a good job on the subject in the Gateway to the Confederacy collection of essays. I understand a new biography on Rosecrans is in the works, which we sorely need so perhaps we will gain some further insight there.

I think Rosecrans suffered from being hard to work with, at least for his superiors. Like Beauregard, he saw himself as the smartest man in the room, and to be fair he usually was. He never forgave Grant for Iuka.

I think Grant was jealous of Rosecrans winning personality, intelligence, battlefield charisma, and likely because while he was fumbling in front of Vicksburg, Rosecrans was winning Stones River. Grant was never man to forget a slight, real or imagined. He put up with Halleck when it was to his benefit, but when he was strong enough, he cast him aside.

The USCT attacked Peach Tree Hill, not Shy’s Hill.

Nor at any point did I say they attacked Compton’s Hill (the 1864 name for what is today for Shy’s Hill).

“… a ludicrous attempt to save a cause that was long lost,” a worthy quote serving as an allegory for both JBH’s leadership of an army group (Army of Tennessee), but his Peter’s Principle-like career as a general officer.