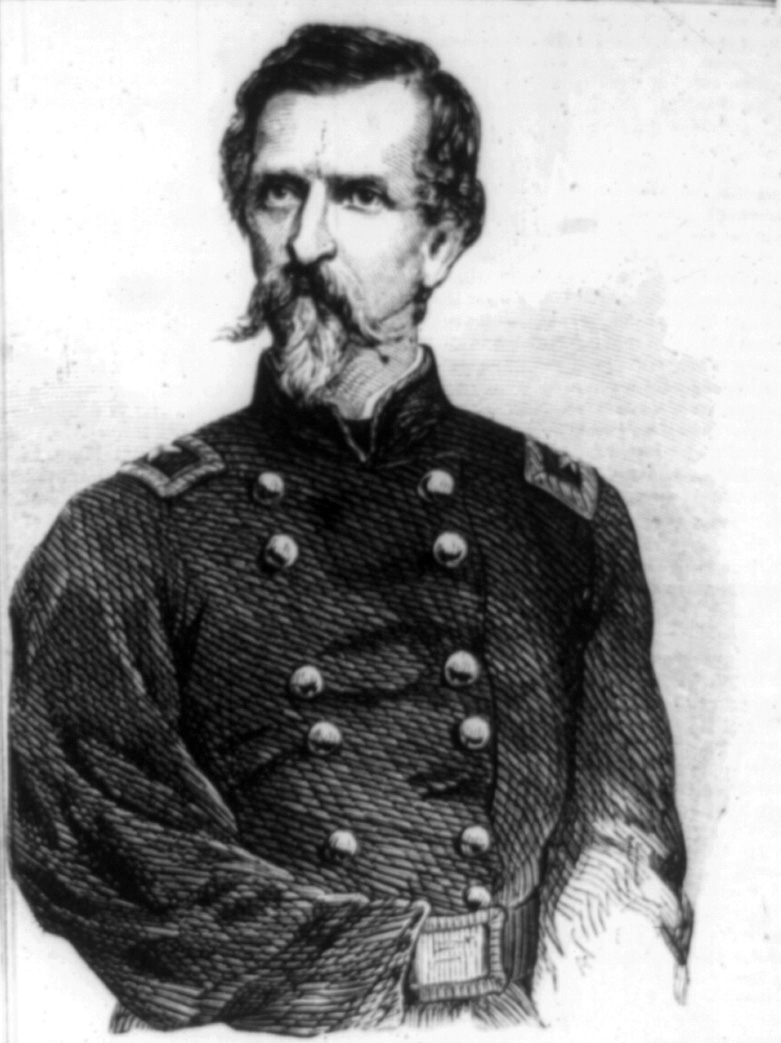

Symposium Spotlight: Phil Kearny

Welcome back to another installment of our 2020 Emerging Civil War Spotlight series. Each we have introduced you to another of our outstanding topics that will be presented at the Seventh Annual Emerging Civil War Symposium August 7-9, 2020. Today we have Kris White preview his talk on fallen leader Phil Kearny:

When Chris Mackowski first told me about the theme for the 2020 ECW Symposium, I was intrigued by the topic. The theme, as he explained, was meant to explore more than commanders who fell in battle and what immediate impact their demise may have led to on the battlefield. Mackowski wanted us to think outside of the box and look at the term fallen in less conventional terms. To me, the traditional tales of the wounding of Stonewall Jackson or Albert Sidney Johnston were off of the table, as was the death of John Sedgwick or James McPherson (the general and not the very-much-alive historian).

In the course of the conversation, I was drawn to a figure who I was introduced to by William Styple in 1994. Bill was signing his latest book covering the life and letters of Holman S. Melcher, an officer in the 20th Maine at the Horse Soldier in Gettysburg. For half an hour, Bill told me about Melcher and his role with the 20th Maine, and then he switched gears and brought up Major General Philip Kearny, Jr. Styple explained that his Belle Grove Publishing Company was named after the general’s former mansion in what was is today, Kearny, NJ. I found Kearny’s story so fascinating that I spent the next three years of my life researching this larger than life man. Thus, when Mackowski called for ideas, I could think of no better candidate for the “fallen leaders” theme than Phil Kearny.

Philip Kearny, Jr., is a “fallen leader” in nearly every sense of the term. During the Mexican War, at Churubusco, Kearny lost his left arm to grapeshot from a Mexican cannon. In the antebellum years, Kearny fell from the graces of high society by filing for divorce from his first wife Diana, then engaging in a public affair with the woman who would become his second wife, Agnes Maxwell. Finally, Kearny was felled by a Confederate bullet at the Battle of Chantilly on September 1, 1862. In the end, the death of Phil Keany, and that of Union general Issac Stevens led to something larger, some 125 years later—the birth of the modern battlefield preservation movement.

Born into New York City’s high society, Phil Kearny was the only child of Susanna Watts Kearny and Philip Kearny, Sr. The elder Kearny was a Havard grad and one of the founders of the New York Stock Exchange. His maternal grandfather was John Watts, the last Recorder of the New York City under the English Crown, and later Speaker of the New York State Assembly— among other titles.

Young Philip’s upbringing in New York society left him wanting for nothing when it came to physical comforts and connections in high society, yet the young man yearned for more than what New York City had to offer him. Like many young men, Philip dreamed of martial glory on the battlefield. His uncle, Lt. George Watts served in the United States Dragoons and on the staff of General Winfield Scott, during the War of 1812. Another uncle, Stephen Kearny, served in the War of 1812 and on the western frontier and was becoming a legend in his own time. The family even had ties to Major General William Alexander, better known as “Lord Stirling,” from the Revolutionary War.

For all of the family’s military service, neither Philip’s father or grandfather approved of him joining the military. Rather, these men wanted Philip to attend college, which he did. Kearny graduated from Columbia College (today Columbia University) and pursued a career in law after graduation.

In 1836, when Kearny was only 21 years old, his grandfather died. Through his inheritance, young Philip instantly became a millionaire. Utilizing his newly found financial independence, Kearny did the complete opposite of most men in his position and joined the army, rather than living the life of luxury.

Through his family connections, Kearny obtained a commission as a lieutenant in the 1st United States Dragoons. This unit also happened to be commanded by his uncle Stephen. Nepotism and connections aside, Phil Kearny was a natural and fearless leader, an outstanding horseman, and a natural cavalry officer.

Two years later, the Secretary of War sent Kearny to France’s Loire Valley, where he attended the prestigious École Royale de Cavalerie at Saumur. The training in France benefited Keanry greatly, as he lacked a West Point commission. Kearny stayed on in France, serving in Algeria with the 1st Chasseurs d’Afrique. In the finest Chausseur (hunter-light cavalry) style, Kearny charged into battle with the reins of the horse in his teeth, and with a pistol in his left hand and a saber in his right. For his battlefield actions, his French comrades dubbed him “Kearny le Magnifique.”

Returning to the United States, Kearny served on the staff of Winfield Scott, married, and resigned from the army. The outbreak of the Mexican War drew Kearny back to the army a few weeks after his resignation.

Commanding Company F, 1st United States Dragoons, Capt. Kearny spent his own money to outfit the entire company with 120 matched dapple grey mounts. Kearny and his unit saw action at Contreras and Churubusco. During an ill-fated charge at Churubusco, Kearny dashed headlong into the Mexican works with one other man, as the rest of his regiment was ordered to call off the attack. The French-trained Kearny took the credo of the Chasseur’s to heart, never retreat. According to one account, Kearny leaped his horse over the Mexican works and reins in his mouth, and pistol and saber in either hand. A Mexican cannon discharged, shattering Captain Kearny’s left arm. Escorted back to American lines, his left arm was amputated as General Franklin Pierce held Kearny’s head still. Future Union General Fitz John Porter recalled, “I remember after Churubusco, going into the hospital and finding Gen. Kearny there wounded. He had lost his arm…I tried to encourage him although I did not think he would recover. He said, ‘Oh, I will be alright; I am going to get well.’”

Ending the war as a major, Kearny stuck to soldiering until 1851. World travels, a bitter divorce, the construction of a new mansion, and new love carried Kearny through much of the 1850s. Ever the soldier, the one-armed officer traveled to France in the late 1850s to offer his services to Emperor Napoleon III at the outbreak of the Franco-Austrian War. While denied a commission, the capable American was allowed to serve as a volunteer on the staff of General Louis-Michel Morris, his former commander from his time in the Algerian Campaign.

Kearny’s second tour of French service carried him to Italy, where he took part in the battles of Magenta, Montebello, and Solferino. During the latter battle, Kearny claimed to be in the thick of battle and in the saddle for some eleven hours. For his actions and service to France, Kearny was awarded the French Légion d’honneur, becoming the first U.S. citizen to be thus honored.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Kearny offered his service to his home state of New York. Unfortunately for the proud officer, his divorce and affair made him a pariah in New York society. And as men like Daniel Sickles received commissions from the state, Kearny— with battle honors spanning four wars and three continents—was turned away.

The artist James Kelly stated:

At the beginning of the war through his political connections he [Sickles] received command of a regiment, and later a Corps, while the distinguished soldier Phil Kearny with his brilliant service in the Mexican War, Algiers and Italy, although a native of New York City, could not get a commission [because of a scandalous divorce] but was compelled to go to New Jersey for a command.

New York’s loss was New Jersey’s gain. The state stepped in and offered Kearny command of their newly formed New Jersey Brigade. The men lacked discipline, apparently. When the general entered their camp for the first time, he was dressed as a civilian, wearing a cap and carrying a cane. When he came upon the guardhouse, he found the men drinking whiskey. The general promptly smashed the bottle with his cane, and in the following weeks, whipped the New Jersey men into excellent fighting shape.

By the time of the 1862 Peninsula Campaign, Kearny was in command of the Army of the Potomac’s 3rd Division, 3rd Corps. Along with fellow 3rd Corps division commander Joseph Hooker, the 3rd Corps boasted the two most aggressive division commanders in the army. At Williamsburg, Glendale, and Second Manassas, the 3rd Corps fought with determination and distinction.

Kearny exposed himself to enemy fire time and again in battle. He looked after the care and comfort of his men. “He inspired an unbounded confidence in all those who had once been under fire with him,” said the Comte de Paris. And proved to be the most capable combat leader at division level in the Army of the Potomac. The general even created the forerunner of the modern divisional patch—a red diamond—to identify his men on the field of battle.

In the midst of a driving thunderstorm, Kearny was killed by a member of the 49th Georgia at the Battle of Chantilly (Ox Hill). Told by one aide to stay away from an exposed part of the battlefield, the impetuous general rode to the exposed section of the line. “What troops are here?” Bellowed the one-armed general. “[T]he 49th Georgia.” Wheeling his horse away, Kearny claimed: “They [the Confederates] can’t hit a barn!” Gunfire mixed with the sound of thunder and Kearny fell from his horse, dead. The ball entered the base of his spine and exited the shoulder, according to one account. Confederate General A.P. Hill ran up to the Kearny’s body and exclaimed, “You’ve killed Phil Kearny, he deserved a better fate than to die in the mud.”

On September 2, Kearny’s body was taken to Union lines under a flag of truce. His body was transported to New Jersey, where his body lay in state in his mansion, Belle Grove. The funeral procession carried Kearny remains through Newark and Jersey City, and he was finally laid to rest in Trinty Churchyard in New York. In 1912, Kearny’s body was exhumed and interred in Arlington National Cemetery. Two years later, an elegant equestrian statue was dedicated to mark the grave of Phil Kearny.

Major General Philip Kearny made an indelible impact on the men of the 3rd Corps. The officers who served under Kearny created the Kearny Medal, denoting their service under the general. Each medal was adorned with the phrase “Dulce ed decorum est pro partria mori,” (It is sweet and proper to die for one’s country). Enlisted soldiers and NCO’s could earn the “Kearny Cross,” a medal for valor in combat. Among the recipients of the Kearny Cross were Anna Etheridge and Marie “French Mary” Tepe, who served as vivandière’s in the 3rd Corps.

It would seem that despite his social setbacks of the 1850s, Kearny was destined for bigger and better things in the Civil War, before his life was cut short at Chantilly. But Kearny had other strikes against him in the Army of the Potomac. Kearny was an outspoken critic of superior officers including George McClellan and John Pope. And in the McClellan’s circles, this would not do.

He also lacked a West Point education. In reality, the education meant much less than did the West Point brotherhood, which dominated the high command of both the Army of the Potomac and its Confederate counterpart, the Army of Northern Virginia. While some historians feel that Kearny could seriously have been considered as the leader of Lincoln’s principal army, I do not share this sentiment. Kearny’s name in high society was tarnished, while the West Point cadre would never allow him fully into their inner circles either. The dearth of non-West Point division and corps leaders illustrates this point alone. Phil Kearny may have had the opportunity to command a lesser army—the James, Gulf, or Shenandoah—-there would be little hope that this outspoken, aggressive, non-West Point, social pariah would ever have a shot at commanding the most famous and political army in the Union.

Yet, for all of his experience and his shortcomings, Kearny brought an aggression that was sorely lacking in the Army of the Potomac. A fighting spirit and frontline leadership that carried on in his former division. A division that saw some of the worst fighting after his death, and sustained some of the highest casualties at Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg.

That same fighting spirit carried into the 20th century when the Chantilly battlefield was threatened by developers. A group of historians banded together in an attempt to save the battlefield where Kearny and Stevens fell. Although much of the battlefield is now developed, their fighting spirit, much like Phil Kearny’s, carried on. And that spirit ushered in the modern age of battlefield preservation.

Had it not been for the fall of the man that General Winfield Scott dubbed “the bravest man I ever knew,” some 50,000 acres of battlefield land may have gone unprotected, and lost to eternity.

You can find out more information about the 2020 Emerging Civil War Symposium by clicking here.

Enjoyable read!

Fascinating… thanks for reintroducing me to this guy. What a life he lead. I’m not one much for biographies but I would consider reading one on him.

There is a new bio due out sometime this year.

Thank you, I’ll check it out.

Visiting Arlington two years ago with my daughter, we found his grave most impressive.

This is a great article; I thoroughly enjoyed it.

https://www.nj.com/hudson/2020/02/bill-to-replace-kearny-statue-at-us-capitol-passes-nj-senate-angering-residents.html

First thing I thought of when I saw this post. Terrible decision.

I was about to post this same article on Kearny’s statue in the US Capitol Building.