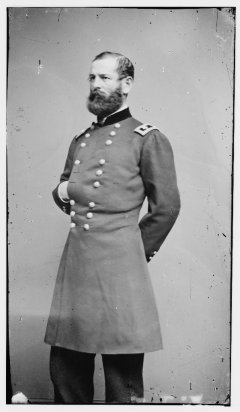

Symposium Spotlight: Fitz John Porter

Welcome back to another installment of our 2020 Emerging Civil War Spotlight series. Each week we have introduced you to another preview of our outstanding presentations that will be shared at the Seventh Annual Emerging Civil War Symposium August 7-9, 2020. Today we look at Kevin Pawlak’s topic in our Fallen Leaders theme, Fitz John Porter.

Welcome back to another installment of our 2020 Emerging Civil War Spotlight series. Each week we have introduced you to another preview of our outstanding presentations that will be shared at the Seventh Annual Emerging Civil War Symposium August 7-9, 2020. Today we look at Kevin Pawlak’s topic in our Fallen Leaders theme, Fitz John Porter.

“Take him for all in all, he was probably the best general officer I had under me.” So wrote George B. McClellan of Fitz John Porter.

At the beginning of the Civil War, Porter’s ascension to command rocketed upward. Porter’s prewar experience justified such a rise. He graduated eighth in the West Point Class of 1845, won brevet promotions in Mexico, served as a professor at West Point, and rode alongside Albert Sidney Johnston in the Utah Expedition.

Despite his climb, Porter’s career soon came crashing down. He ran afoul of the Lincoln Administration’s management of the war and was a public critic. In the Second Manassas Campaign, where he served under John Pope, Porter became Pope’s scapegoat for that disaster.

Porter’s associate and the man who gave him corps command in the Army of the Potomac, McClellan, tried to shield Porter from censure. However, McClellan’s removal from command on November 7, 1862, opened the door to Porter. Three days later, Porter lost his command and soon fell under arrest to be put on trial.

John Pope’s charges against Porter amounted to five counts of disobeying a “lawful command of his superior officer” and three counts of misconduct in the face of the enemy during the Second Bull Run campaign. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton personally approved the nine men presiding over the trial. In this highly politicized case, the stakes for Porter were high. A simple majority of judges was all that was required to convict Porter while a two-thirds majority might inflict the death penalty.

The court opened on December 3, 1862, and lasted until January 6, 1863. On January 21, the court declared Porter guilty of both charges. He lost his rank in the United States Army and was barred from ever holding a position in the Federal government.

Porter did not sit idly by and fought the decision for the next 24 years. The case remained politically charged. The 1878 Schofield Board suggested an exoneration of Porter. However, it was not until 1886 that a Democrat-controlled Congress returned Porter to the rank of colonel in the United States Army. He retired five days later.

Have you purchased your 2020 Emerging Civil War Symposium tickets yet? If not, you can by clicking here.

What a disgraceful episode. Pope clearly targeted Porter to take the blame for his ineptitude. Who knows how history might have been different if Pope didn’t have the political backing to destroy Porter’s career?

Porter is the definition of “overrated”.

I made no claims of Porter’s abilities, but Pope proved that he was incompetent. Surely Porter could have been used to some advantage, somewhere – rather than going through the trial process and losing his rank on trumped up charges originating from Pope to cover his blunders.

Ultimately Porter was no big loss to the Union military cause. Could he have been “used to some advantage”? Sure. Pope was actually used to some advantage, as well – in Minnesota. And the more time you spend reading Porter’s “injudicious” correspondence, the less offended you will be by his cashiering – even if it was for the wrong reasons.

Porter was guilty of using his New York press connections to publicly involve himself in what was an increasingly political debate. His arrogance, like McClellan’s, was his undoing.

This is “spot on”. Porter’s correspondence with an anti-administration publisher (Marble) about military affairs while on active duty was improper, to put it nicely, and may well have crossed the then-Articles of War. He was justly under suspicion based on those comments and similar comments to others, such as Kennedy. While the specific charges brought against him by Pope were not supportable, he was far from a “hero” or “martyr”. His overall performance at Second Bull Run has been labeled “mediocre” by no less an authority than John Hennessy and others – Spruill and Jermann- have pointed out how Porter flubbed opportunities at the battle. He has gotten too much credit for Gaines’ Mill and Malvern Hill (a West Point plebe could have chosen the ground in both of those fights – and GM resulted in his ultimately being routed from the field). His “victory” at Hanover Church involved poor tactics by Porter that paled next to the even worse tactical performance of Branch. Marvel is apparently working on a biography for UNC Press. I expect much objectivity given an observation by Marvel in an end note in his Stanton biography, which rips Eisenschimel’s book about the courts martial as hagiography.

I would like to hear some words from Porter’s viewpoint on not attacking in the afternoon at Antietam. Was it simply a matter of following orders, the end? Did he try to get his men into the battle. Was he at that time under a cloud, could he not get into that sanguine September battle and clear his name.

There is a chapter on this in Bradley’s “The Antietam Effect”, but essentially the whole thing was a hit piece put out by Thomas Anderson, one of Porter’s political enemies, to smear Porter after his court-martial had been overturned.

Porter himself pointed out, rightly, that he had maybe 4,000 troops in the centre. Warren’s little brigade had been sent to reinforce Burnside (who had them guard his HQ at the Rohrbach House, and kept them out of the action), and two of Morell’s brigades had been sent to reinforce Sumner on the right. This left Porter with the two brigades of regulars (about 2,500 men) and Barnes’ brigade (about 1,500 men of whom ca. 700 were the green 118th Pa whose muskets didn’t work).

The chances of success for less than 4,000 men advancing over an open field for a mile in the face of a large force of artillery and then making an uphill assault against the enemy infantry. William Powell, who was AAG of the regulars across the creek, answered that any attack would have been broken up by the rebel artillery and wouldn’t have reached the enemy position.