The Unending War for Ten Union Generals

In a blog post published last July about Brigadier General Thomas W. Egan, I stressed how countless disabled Civil War veterans endured decades of chronic pain and emotional distress long after the guns of the Civil War fell silent. In her groundbreaking book Bodies in Blue: Disability in the Civil War North (2019), Dr. Sarah Handley-Cousins used Union Major General Joshua L. Chamberlain – among many others – as an example of a high-ranking officer who suffered non-visible disabilities (not easy to spot with the naked eye, like amputees) that physically and emotionally tormented him for years after the Civil War. An infection ultimately took his life 50 years after being wounded.[1]

This got me to thinking: What other Union generals experienced what Chamberlain did as a result of their wartime service? About one-fifth of Union generals experienced accidents leading to injuries and a half or more suffered one or more non-fatal wounds. (This number doesn’t include brevet brigadier generals.) I’ve identified 10 generals whose war continued long after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. Some of these men endured years of agony from their wounds or injuries. These disabilities robbed them of the ability to perform even simple tasks and certainly left them feeling emasculated and disheartened. For the unlucky ones – depending on how you want to look at it – wounds or injuries cut years off their lives. These are their stories.[2]

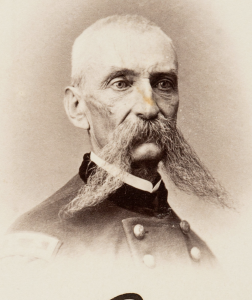

1. Brigadier General James Barnes (1801-1869)

Barnes graduated from West Point fifth in the Class of 1829, four spots behind Robert E. Lee and eight spots ahead of Joseph E. Johnston. He resigned from the army in 1836 to become a civil engineer but returned to fight in the Civil War. On July 2, 1863, while leading a division at Gettysburg, the 61-year-old general suffered a wound to the left leg from a shell as he sat mounted next to Colonel William S. Tilton. The wound forced Barnes to turn over command of his division two days later. By 1864, Barnes was still suffering from his Gettysburg wound, further complicated by malaria. He never returned to the field. In 1869, Barnes reportedly died from liver congestion, but his tombstone tells another story: “A graduate of the West Point Military Academy, he was actively engaged throughout the late war and died of disease contracted in the service of his country.”[3]

2. Major General Alexander Asboth (1811-1868)

Asboth suffered his first wound at Pea Ridge when a Confederate musket ball penetrated his right arm, fracturing it. He suffered another two wounds during a charge at the Battle of Marianna, Florida, on September 14, 1864. The first fractured his left arm in two places and the second shattered his left cheekbone. Surgeons could not locate the ball, so it remained embedded in his cheek. The wound impaired his sense of smell, sight, and hearing. When doctors finally discovered the ball in 1866, the stubborn general chose to delay the surgery to sail to Argentina to accept the position of U.S. minister there. This decision would cost him his life. “He has long been an invalid and a great sufferer,” a correspondent from Buenos Aires reported before his death in January 1868.[4]

3. Brigadier General Egbert B. Brown (1816-1902)

The nephew of Major General Jacob Brown, Egbert Brown sailed the Pacific Ocean for four years on a whaling ship before the war. While commanding a garrison of troops at Springfield, Missouri, during General John S. Marmaduke’s invasion of Missouri, Brown was struck in the left arm by a musket ball, fracturing it and severing his bicep. Major General Samuel R. Curtis feared that he would lose the arm or perish from the effects of its amputation. Surgeons saved Brown’s arm, but the wound continued to afflict the general until he resigned in 1865. A year later, he reported his arm was useless. Brown regained limited mobility by 1870, but three years later, he lost mobility, leaving him crippled for the rest of his life.[5]

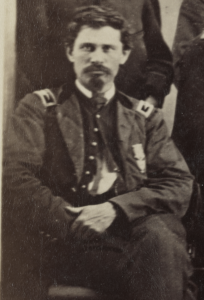

4. Brigadier General Robert F. Catterson (1835-1914)

Bob Catterson made an impressive ascension from sergeant to brigadier general by the end of the Civil War. While serving as a captain at Antietam, he suffered four wounds in a single day. One pierced his buttocks and lacerated his sphincter. The second damaged his left thumb. The third struck his left foot and lodged in the middle of his heel bone. The fourth and last struck him in the right kneecap. Despite his desperate condition, Catterson reported that his wounds were not dressed for days. After the war, a doctor found that when his first wound healed it had formed a pouch of coagulated blood near his rectum. This interfered with his ability to defecate, limiting his ability to perform this basic bodily function.[6]

5. Brigadier General Morgan H. Chrysler (1822-1890)

Prospect Hill Cemetery

Valatie, New York. (Find A Grave)

Chrysler served in most of the Army of the Potomac’s major battles until his regiment was mustered out in 1863. After reenlisting, he led a cavalry regiment and brigade in the Department of the Gulf. On July 28, 1864, during a skirmish at Morgan’s Ferry Road, he was severely wounded when a ball struck him in the sternum and exited his right shoulder. A farmer before the war, Chrysler was unable to return to work because of the wound. By 1870, he could hardly extend his right arm above his shoulder without pain. Likewise, any pressure placed on the scar caused him to cough and his laryngeal and pharyngeal muscles to contract. Chrysler suffered from spasms if he spoke loudly or if he swallowed large pieces of food. At night, he experienced dyspnea and the sensation that the lower part of his trachea was being restricted. By 1879, his right shoulder drooped, his right eye acted independently of the left, and he experienced numbness to his left side.[7]

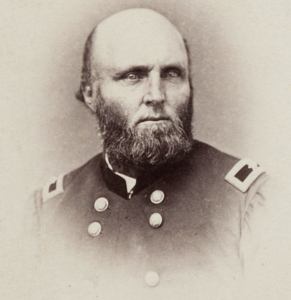

6. Brigadier General Lysander Cutler (1807-1866)

Cutler spent most of his army career in the famed Iron Brigade and rose to division command. On August 28, 1862, at the Battle of Brawner’s Farm, he was wounded when a ball smashed into his right thigh. Nearly two years to the exact day of this wound, he was hit in the face by a shell at Weldon Railroad, causing disfiguration. Broken in health, Cutler resigned and returned home an invalid. He continued to grow weaker as a result of his wounds. On July 19, 1866, Cutler suffered his first stroke. The second occurred six days later, leading to total paralysis of the right side of his body. He died five days later. Cutler’s war comrade and the governor of Wisconsin, Lucius Fairchild, declared, “Distinguished for his services, covered with honorable scars, filled with years and glory, he goes to his grave deeply mourned by the entire people of a sorrowing State.”[8]

7. Brigadier General Samuel Beatty (1820-1885)

A farmer and sheriff of Stark County, Ohio, before the war, Sam Beatty served in most of the major battles of the Western Theater without suffering a wound, but not without injury. On September 19, 1863, during the Battle of Chickamauga, his horse slipped and fell on him. He dislocated his left shoulder and suffered a small wound near his upper shoulder. Beatty suffered his second serious injury in March 1865, near Stevenson, Alabama, when he jumped from a stationary train and accidentally collapsed onto a railroad tie. He damaged his left hip and suffered an inguinal hernia to his right side. The farmer’s left arm and shoulder were nearly useless after the war. In 1877, he was still suffering from the hernia sustained during the train accident. His hip was lame and he usually wore a sling around his arm. He continued to suffer from his injuries for the remainder of his life until his death on his Massillon farm at the age of 64.[9]

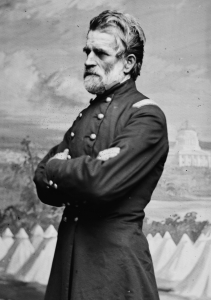

8. Brigadier General Manning F. Force (1824-1899)

On July 22, 1864, during the Battle of Atlanta, a Confederate ball punctured General Force’s face below his left eye and exited near his right jawbone. The bones in his mouth were shattered and he could not speak. After the war, he served on the Superior Court of Cincinnati as a judge until 1888, when poor health and fatigue forced him to step down. A year later, Dr. J.T. Hayes of Erie County, Ohio, reported Force was experiencing neurological changes – disturbed speech, twitching muscles in his face and neck, and the loss of sensation in arms, hands, and upper body – which he attributed to the general’s Atlanta wound. Force also lost control of his bladder and rectum and suffered from erectile dysfunction. Hayes concluded that his death in 1899 was “undoubtedly due to destructive change of nervous structure and its complications, such as organic disease of heart, disturbance digestive tract, etc.”[10]

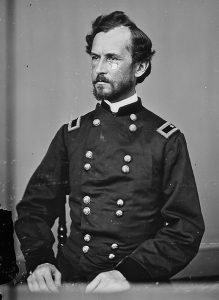

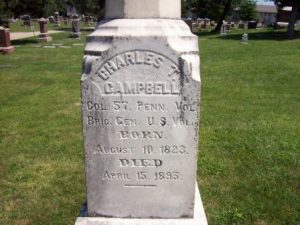

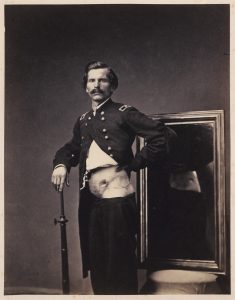

9. Brigadier General Charles T. Campbell (1823-1895)

Yankton City Cemetery,

Yankton, South Dakota. (Find A Grave)

A Mexican War veteran, Campbell matched Joshua Chamberlain’s six wounds during his service in the war. He suffered three wounds at the Battle of Fair Oaks on May 31, 1862. Campbell was shot in the right wrist, groin and pelvic bone, and left leg. Less than seven months later with his arm still in a sling, Campbell was severely wounded in three places at Fredericksburg. One ball passed through his body, cutting into his liver, and two through his arm, shattering it from the wrist to elbow. His colleague Brigadier General Alexander Hays teased that Charlie Campbell “does not know the different between minie-balls and Brandreth’s pills.” Sarah E. Campbell’s pension claim reported that “he came out of the war completely disabled.” By 1880, Campbell’s right hand was nearly useless and he suffered from ankylosis in his right elbow. He needed the assistance of another person to put on or to remove his clothing, bath, and to get in or out of a vehicle. A lame back and rheumatism in his left arm and shoulder further complicated his condition. In 1895, Campbell fainted and fell down a flight of stairs at his hotel in Scotland, South Dakota, causing him to break two ribs and an arm. He ultimately succumbed as a result of internal injuries.[11]

10. Brevet Brigadier General Cassius Fairchild (1829-1868)

The older brother of Brigadier General Lucius Fairchild (who lost his left arm during the war), Cassius Fairchild was seriously wounded in the thigh at Shiloh. One account stated that the wound was so close to his hip-joint that surgeons couldn’t amputate his leg. After the war, the wound reopened while he acted as a pallbearer during a friend’s funeral. On his deathbed at his father-in-law’s home, Fairchild chose to marry his fiancée, Mary C. Haney. An obituary published by the Society of the Army of the Tennessee gave a heartrending account of this event. It stated that the “two hearts which had loved so tenderly, and had looked forward to so much happiness on earth, were united. It was not the happy bridal scene which had been hoped for, and there were tears instead of smiles, but the hearts which had loved so well, were united.” Fairchild died days after his marriage. His tombstone at Forest Hill Cemetery in Madison, Wisconsin, notes that he perished due to his Shiloh wound.[12]

Dozens of other generals not included here experienced lingering injuries or wounds (physical or psychological) once they transitioned back to civilian life. It impacted their jobs, affected their relationships with family members, and diminished their self-worth. Some got on with their lives, while others died as a result of these injuries or wounds. Most fell somewhere in between the two, functioning as best as they could as they lived out their final years in pain and disabled. For them, a longer second war commenced once they returned home from the American Civil War.

Endnotes

[1] Sarah Handley-Cousins, Bodies in Blue: Disability in the Civil War North (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 2019), 73-75; Brian Matthew Jordan, Marching Home: Union Veterans and Their Unending Civil War (New York: W.W. Norton, 2014), 3-4, 7.

[2] Jack D. Welsh, Medical Histories of Union Generals (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1996), xv.

[3] Welsh, Medical Histories of Union Generals, 17; “Obituary: Major-General James R. Barnes,” The Evening Telegraph (Philadelphia, PA), February 13, 1869.

[4] Welsh, Medical Histories of Union Generals, 7-8; The Evansville Journal (Evansville, IN), February 28, 1868; Joseph K. Barnes, The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion (1861-65) (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1875), 389; The Army & Navy Official Gazette, Vol. 2, 1864-65 (Washington: Printed at the Office of F. & J. Rives, 1865), 274-75.

[5] Welsh, Medical Histories of Union Generals, 40-41; Index to the Miscellaneous Documents of the House of the Representatives for the First Session of the Fiftieth Congress, 1887-88 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1889), 179; James G. Wilson and John Fiske, eds., Appletons’ Cyclopædia of American Biography. Vol. 1 (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1891), 398.

[6] Welsh, Medical Histories of Union Generals, 62-63; Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, IN), April 12, 1914.

[7] Welsh, Medical Histories of Union Generals, 68-69; Edward A. Collier, A History of Old Kinderhook (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1914), 476-77; The Miscellaneous Documents of the House of the Representatives for the Second Session of the Fifty-Second Congress, 1892-93 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1893), 450.

[8] Welsh, Medical Histories of Union Generals, 88-89; “Death of General Cutler,” Dodgeville Chronicle (Dodgeville, WI), August 2, 1866; “The Late Major-General Lysander Cutler,” The Evening Telegraph (Philadelphia, PA), August 6, 1866; Frank A. Flower, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin (Chicago: The Western Historical Company, 1881), 792.

[9] Welsh, Medical Histories of Union Generals, 24-25; Society of the Army of the Cumberland, Seventh Reunion. Grand Rapids, Michigan. 1885 (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co., 1886), 229-232; William H. Perrin, ed., History of Stark County, With an Outline Sketch of Ohio (Chicago: Baskin & Battey, Historical Publishers, 1881), 977-78.

[10] Welsh, Medical Histories of Union Generals, 117; Military Essays and Recollections: Papers Read Before the Commandery of the State of Illinois, Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States. Vol 1 (Chicago: A.C. McClurg and Co., 1891), 306; Glenn W. LaFantasie, “Unknown Soldier: Manning Ferguson Force, the Hero of Atlanta,” HistoryNet (Accessed March 13, 2019), https://www.historynet.com/unknown-soldier-manning-ferguson-force-the-hero-of-atlanta.htm; Frances Horton Force Pension Report, May 17, 1900, 56th Congress, 1st Session, House of Representatives, Report No. 1567.

[11] Welsh, Medical Histories of Union Generals, 52-53; “Brig. Gen. Charles T. Campbell, a Veteran of Three Wars,” The Indianapolis Journal (Indianapolis, IN), April 21, 1895; “Mexican War Veteran Dead,” The Weiser Signal (Weiser, ID), April 25, 1895; Sarah E. Campbell Pension Report, April 12, 1898, 55th Congress, 2d Session, Senate, Report No. 860; George O. Seilhamer, “Memoirs of Men of Mark: Gen. Charles T. Campbell,” in The Kittochtinny Historical Society, Papers Read Before the Society, February, 1915 to April, 1922. Vol. 9 (Chambersburg, PA: Franklin Repository Press, 1923), 201-203; George T. Fleming, ed., Life and Letters of Alexander Hays: Brevet Colonel United States Army Brigadier General and Brevet Major General United States Volunteers. Complied by Gilbert Adams Hays (Pittsburgh, 1919), 288, 590.

[12] Watertown Republican (Watertown, WI), October 28, 1868; “Death of Cassius Fairchild,” Mineral Point Weekly Tribune (Mineral Point, WI), October 28, 1868; “Death of General Cassius Fairchild – Brief Biography of the Deceased – Drowning Case,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), October 26, 1868; “Critical Condition of General Cassius Fairchild,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), October 16, 1868; Report of the Proceedings of the Society of the Army of the Tennessee at the First Annual Meeting, Held at Cincinnati, Ohio. November 14th and 15th, 1866 (Cincinnati: Published by the Society, 1877), 166-67; Consul W. Butterfield, ed., History of Dane County, Wisconsin (Chicago: Western Historical Company, 1880), 535-36.

I have recently published ”I am a Soldier, First and Always: The Distinguished Career of Winfield Scott Hancock” as a historical fiction. The events and actions are based on factual information including his severe wounding on the third day at Gettysburg — a wound that would plague him for the remainder of his war, eventually take him from command during the overland campaign, and bring on a disease that would eventually claim his life. The book offers insight into the General’s character. Interested folks can find the two volume set — Rebellion and Turning Point — on Amazon.

Well stated, Frank.

Interesting reading; thanks for posting this.

Too often histories of the War stop with Lee’s and Johnston’s surrenders, or the Grand Review of the Union Armies. And Reconstruction had been viewed solely through the lens of racial injustices or transformation. But the Reconstruction was also of the ruined physical and economic landscape of the South, and of the broken bodies, minds and hearts of the participants, Union and Confederate. It is one of the keys in understanding why what happened in post war America occurred. I always read advocacy histories in this light, to better understand both the anger and the romanticize view of the War.

One of the other generals, was Brigadier General Jasper A. Maltby, who suffered horrendous wounds on June 25, 1863, during the Forty-fifth Illinois’ attack in the Vicksburg crater (3rd Louisiana Redan/Fort Hill). He died in late 1867, in Vicksburg. Originally a sickness/disease was blamed but later it was concluded his wounds from June 25, 1863 caused his early demise.

A morbid, but fascinating post. Thanks for sharing!

Looks like you mentioned the wrong Springfield on the Egbert Brown story. That’s a fascinating battle, Second Springfield (Missouri), January 8, 1863. It and the Battle of Hartville, MO three days later – my hometown.

Thanks for correcting. The point of the Confederates’ furthest advance in the Battle of Springfield, MO was about where my uncle’s auto body shop was on Walnut St south of Park Central Square. I believe some historic markers were placed a few years ago. The Battle area is in the middle of a large city, today.