New Articles Will Help You Rethink McClellan

Probably the most notable thing about George McClellan’s final month and a half in command of the Army of the Potomac are the zingers Lincoln tosses at the general for the army’s inactivity. By that point in their relationship, even Lincoln’s seemingly bottomless reserves of patience had become noticeably frayed. When Lincoln expressed concerns about McClellan’s “overcautiousness,” McClellan replied that it was his intention “to advance the moment my men are shod & my cavalry are sufficiently remounted to be serviceable.”

Probably the most notable thing about George McClellan’s final month and a half in command of the Army of the Potomac are the zingers Lincoln tosses at the general for the army’s inactivity. By that point in their relationship, even Lincoln’s seemingly bottomless reserves of patience had become noticeably frayed. When Lincoln expressed concerns about McClellan’s “overcautiousness,” McClellan replied that it was his intention “to advance the moment my men are shod & my cavalry are sufficiently remounted to be serviceable.”

Lincoln replied with a zinger that has since attained a fame of its own: “Will you pardon me for asking what the horses of your army have done since the battle of Antietam that fatigues anything?”

“I am just as anxious as anyone, but am crippled by want of horses,” McClellan told his wife, complaining that Lincoln’s snarky note “was one of those dirty little flings that I can’t get used to when they are not merited.” Lincoln later apologized, but the strain between the two men was so great by then they were no longer really listening to each other.

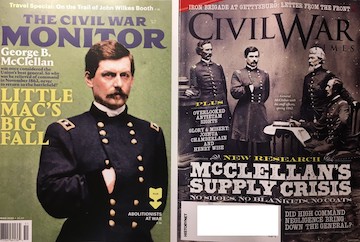

McClellan was hampered during this period by legitimate supply issues, and a pair of coincidental cover articles in the most recent Civil War Monitor and Civil War Times explore this time in interesting detail. Both articles are worth a look.

In Civil War Monitor, my friend George Rable wrote an article titled “Little Mac’s Big Fall: An Inside Look at the Decision to Remove George B. McClellan from Command of the Army of the Potomac.” George’s article breaks down the tension between Lincoln and McClellan and the very real supply issues McClellan faced—as well as McClellan’s very real doubts—and covers the aftermath and fallout of the decision to remove McClellan from command.

Meanwhile, in the latest Civil War Times, which just showed up in my mailbox today, historian Steven R. Stotelmyer penned an article titled “McClellan’s Supply Crisis: Were Supplies Deliberately Withheld from the Army of the Potomac After Antietam?” The cover story, which touts new research, provocatively asks, “Did high command negligence bring down the general?”

As it happens, I’ve spent a lot of time in this post-Antietam period myself lately. I recently turned in the manuscript for my latest book to the University of Tennessee Press for their Command Decisions in the Civil War Series. The book looks at the critical decisions that shaped the battle of Fredericksburg, and it examines McClellan’s replacement with Burnside as the first critical decision of the campaign.

Even just reading the Official Records from this period, particularly the correspondence of McClellan, Herman Haupt, Montgomery Miegs, and (with a careful eye) the slippery Henry Halleck, one can see that the army suffered from severe supply shortages for a variety of reasons. Add to that the journals of George Gordon Meade, Charles Wainwright, and other officers—all of whom complained about shortages—and it’s clear that McClellan wasn’t just making up phantom excuses.

But equally apparent by reading Lincoln’s side of the argument is that McClellan seemed completely oblivious of time—“the question of time, which can not, and must not be ignored,” as Lincoln put it on October 13. Tuned in to military matters, McClellan was tone-deaf and blind to political matters. The fall elections were in full swing, and with them, huge implications for the Union war effort. Lincoln felt the pressure intensely, and he tried (unsuccessfully) exerting that pressure on McClellan.

Lincoln even made an example of Don Carols Buell, whom he fired for inactivity once the western states were done voting. Little Mac got the hint, but only barely.

Kevin Pawlak and I discussed this period in an ECW podcast back in November, for the anniversary of McClellan’s sacking (check out more info here and additional resources here). I’d also recommend a great essay by Brooks Simpson on the subject, “General McClellan’s Bodyguard: The Army of the Potomac After Antietam” which appears in the Gary Gallagher-edited The Antietam Campaign (UNC Press, 1999).

But as a first stop, check out the most current issues of Civil War Monitor and Civil War Times for some solid writing and research. These magazines (and CWT’s sister publication, America’s Civil War) have both been doing some exceptionally thought-provoking work over the last few years, raising the bar for all of us who are writing history for public audiences.

If you thought you knew McClellan, and you enjoy him as the butt of jokes, there’s reason to reconsider him—at least a little.

Thanks for another interesting post. Looking forward to your book.

Thanks!

Excellent points, Chris. I’ve read Stotelmyer’s article, which clearly explained that McClellan faced real problems. But I also came away thinking that the general himself could have been more proactive in resolving the problems (such as moving all or part of the army closer to Washington and/or a railroad to speed resupply) and moving forward. As on the Peninsula and Second Manassas, McClellan waited for the situation to fit him, rather than the other way round. Even without the political differences, I can understand Washington getting fed up with him and that attitude over time.

McClellan’s problems were real, for sure. But it’s also true that he was probably the greatest logistics person the army had at the time, particularly after building the army practically from scratch in the fall of 61/winter of 62. It’s what I would call a Truman Moment: where does the buck stop? Had McClellan taken ownership of that question, he might very well have been able to solve his own problems, but he was ready to pass the buck instead.

There’s only so much being good at organizing logistics can do if those supplies don’t exist in the first place.

Chris:

The “at least a little” caveat at the end of your interesting post says it all. McClellan probably wasn’t as bad as most Civil War fans think. However, he was still pretty bad. His performance during the Seven Days campaign was inexcusable.Grant probably hit it on the button when he diplomatically said McClellan’s rise was too fast and came too early in the war.

In McClellan’s defense: In the early weeks of the CW, he was a strong advocate of building a formidable inland navy made up of timberclads and ironclads. At the time, the creation of warships that could operate on rivers, lakes, bayous, etc;. was still being debated;

McClellan was always his own worst enemy. He had legit issues in the fall of 62, but he also stood in his own way of getting many of them solved. He doesn’t deserve all the fault, although he does deserve a lot of it.

Poor McClellan, whenever I think of him missed opportunities come to mind. I will check out the mentioned articles to see if they can sway me some though.

If missed opportunities intrigue you, read Alan Taylor’s, The Civil War of 1812. It’s an excellent book on that War, the best in my opinion by far. Canada could have been ours by God, at least parts of it, if it hadn’t been for gross incompetence and blundering.

I found the Civil War Times article interesting. When considering the state of the Union Army, I think it is also important to consider the state of the Confederate army as well. Stotelmyer cites diaries and other sources that provide insight into the the poor state of the Federals, but I would not expect the average Confederate was writing home at that time about an abundance of supplies, food, shoes, etc. I also look at the inability of McClellan to maintain a positive relationship with the administration. Ultimately an Army commander in war is in a difficult position where he has to manage the activities of his direct military subordinates, but also has to manage a relationship with his boss, who is very likely an elected official, monarch, dictator, etc. McClellan simply failed here. A question we of course cannot answer is if McClellan had been able to maintain a positive relationship with the administration, would it have made a difference in his ability to obtain supplies? I also wonder if McClellan’s army was well supplied, would he have had another reason for not engaging? Would he have been “severely outnumbered” and unable to advance? I certainly do not claim to know but I find it interesting to consider.

McClellan was a Democrat trying to win a war for a Republican administration. That explains 80% of the conflict between the two groups. The heart of the matter is if McClellan had won the war (he came close until Johnston G.W. Smith was replaced with Lee) he would have been elected president. It worked for Jackson, Taylor, Washington, and after the war for Grant and Eisenhower.

McClellan was a difficult man, but so were a variety of other generals. Being a Democrat ensured that his personal shortcomings would be that much worse. As for Halleck, if a general was not his friend he would actively undermine them, as he did to McClellan, Burnside, Hooker, and Meade. This explains a lot of the problems the Union faced in Virginia.

I haven’t read Stotlemeyer’s article cause I can’t find it, however Micheal T. Griffith’s article “Answering Some Criticism of General George B. McClelland” is very interesting! He also recommends Steven Stotlemeyer’s book “Too Useful to Sacrifice.” I must say Griffith’s article has caused me to begin to look at Little Mac, along with article, from a different perspective!

Thanks

Chris

I am also impressed that a retired General Lee named McClelland as the most effective opposing general he ever met. Lee is not known as a man to harbor ill feelings so I think it says something that he didn’tname Grant, Sheridan or Sherman before McClelland; and Lee’s first major defeat did come w/McClelland.

Time: the age-old difference in perspective between the trained military professional and the civilian politician. To the politician time controls the bellwether of public opinion, while it is the bane of the military professional. What commander would not like adequate time to train, equip, and plan. Food for thought: the politician fired his slow general 2 days after the last of the mid-term elections. The day before he was sacked that same general was moving army corps 20 miles a day.

Steven

How much of a choice do you think Lincoln had of Not removing him?

For political reasons probably very little choice. It has been my experience that popular history doesn’t want to deal with that because it might portray the martyred Lincoln in an unfavorable light. The military realm is another matter. He was not a bad general. It was an aggressive McClellan that pursued Lee thru Maryland. McClellan accomplished his campaign objectives and in the process inflicted upon Lee the greatest casualties ever suffered by the Army of Northern Virginia in the bloodiest day’s combat in our nation’s entire history. In the post Antietam period the supply crisis was genuine and it was crippling. It was made worse by political machinations behind McClellan’s back. He did not have the slows as much as Lincoln had the fasts. The CWT article is a condensed part of the last chapter of my book “Too Useful To Sacrifice: Reconsidering George B. McClellan’s Generalship in the Maryland Campaign from South Mountain to Antietam.” If you find the article interesting I think you may find book interesting as well. But beware, it may cause you to rethink some things you thought you knew regarding George B. McClellan.

Thanks, I didn’t realize the political pressures on Lincoln

Steve

Is this a precursor to McCarthy and Truman,

You mean MacArthur? I don’t know. I have a saying I live by: if it didn’t happen in September 1862, it didn’t happen. Like Dirty Harry said, “A man just has to realize his limitations.”

Yes, I meant MacArthur, thanks. I know there was tension between Mac & Roosevelt. What is it about military people that makes become so arrogant?

Steven

Just finished reading your Civil War article on McClellan, thank you, you seem to agree with Micheal Griffith. If Thomas Scott brought the supply situation to Stanton’s attention, shoes and clothes arriving at the wrong places, why wasn’t the situation corrected? One would think regardless if one where political or professional, the condition of soldiers would come first. It’s quite evident from sources Lincoln was aware of the truth.

The supplies began showing up after Scott’s visit in late October, almost too late to be of any use. I agree, one would think the condition of the soldiers would come first. Yes, Lincoln was aware of the true situation when he visited Antietam in early October (he witnessed a food riot- it’s in my book). As I have asserted it was not so much McClellan having the slows as it was Lincoln having a bad case of the fasts. Because of his Secretary of War’s intense hatred of McClellan thousands of soldiers suffered in the autumn chill of 1862. Was Stanton acting on his own or with Lincoln’s knowledge? It’s not entirely clear. Either way it cast the martyred president in an unfavorable light. As constitutional historian John W. Burgess wrote, “it is very nearly certain that there were some who would have preferred defeat to…victory with McClellan in command. It was a dark, mysterious, uncanny thing, which the historian does not need to touch and prefers not to touch.”

Is the desire for historians not to touch to mysterious to ever figure out or to personally

Painful, fearful for one might find, or just too insignificant?