Bucklin’s In Hospital & Camp: “My Desired Sphere” (Part 2)

In Hospital and Camp, A Woman’s Record of Thrilling Incidents Among the Wounded in the Late War by Sophronia E. Bucklin

In Hospital and Camp, A Woman’s Record of Thrilling Incidents Among the Wounded in the Late War by Sophronia E. Bucklin

Continuing with the primary source read-along! You can find the free e-book and we’re on chapters three and four this weekend. (Find the notes for one and two here.)

Chapter 3

We find Miss Bucklin settling into a routine at Judiciary Square Hospital, but the medical staff refuse to let her assist with dressing wounds or operations. Not an uncommon situation for women arriving at these Civil War hospitals.

She mentions the hospital wards and wings. This was an innovation started during the Civil War as hospitals because an acceptable feature in mid-19th Century society. Medical authorities believed that hospitals had to be large and airy with good ventilation. In the newly built hospitals during the war, many were long buildings either in rows or extending out from a central point (like spokes of a wagon wheel). These buildings tended to be quite open inside. Hospitals organized by “ward,” often trying to separate the critically ill or injured from the others. It should be noted that these practices applied to “base hospitals” or the hospitals in the cities—not field hospitals or front line dressing stations.

“I dropped into my desired sphere at once, and my whole soul was in the work.” This sentiment is commonly found in the journals or writings of good Civil War nurses. They found a purpose and a passion in their work which helped them focus and overcome the difficulties. She also uses the word “sphere”, a common word used to separate the ideas of male and female work in the 19th Century. Women were supposed to control the “sphere of the home”. Interestingly, Bucklin uses the word to imply that she was still in a woman’s sphere of influence as dictated by society even though she was not within the walls of a home. She sees nurses as a woman’s skill set and a proper place in the national crisis.

When I first started studying Civil War medicine, I was fascinated to learn about the “sick diets” and the “dietary cooks” in these larger hospitals. In Confederate nurse Kate Cummings diary, she gives good examples of guys trying to cook in the hospitals; the common practice at the beginning was to have convalescent soldiers act as nurses, cooks, and help with the housekeeping. And that was a bit of a disaster…leading to a little more acceptance of women in the hospital setting. The attitudes tended toward, “Well, fine! Let them come do the housework and cook the meals.” Sick and injured needed specific, healthy food. Recommendations from medical professionals and plain common sense generally dictated the “special diets” for the ill and wounded. Typically—as Bucklin points out—it was plain, healthful, easy to digest food. The menu/diet changed if necessary depended on the individual patient’s needs.

Nurse Bucklin gets away with distributing care package food to her patients and saw it as a way to boost morale, but was it always a good idea? Nope. Confederate hospital matron Phoebe Pember had significant trouble with hospital visitors bringing unhealthy foods, sneaking it to the patients against doctor’s orders, and those patients suffering severe digestive pains. Sometimes, there was a reason for the special diet and doctor’s orders.

Chapter 4

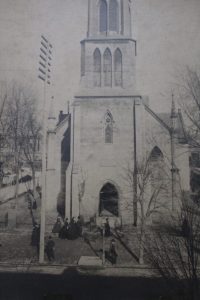

Epiphany General Hospital in Washington City was comprised of two religious buildings: Church of the Epiphany on G Street and the nearby Baptist Church on 13th Street. The church on 13th Street is no longer in existence, but Church of the Epiphany still stands and has an active congregation. As the Civil War began, that church experienced a split; attended by southern and northern politicians along with locals, the congregation went through its own secession crisis. For example, Jefferson Davis and his family left the church while Edwin Stanton quickly volunteered the church’s building for use as a hospital.

Women had skill sets that military doctors needed—whether they wanted to admit it or not. From organizing kitchens to overseeing the laundry or taking time to listen to the soldier-patients, years of learning and home-making had given these volunteer nurses their unique approaches and skills that transformed military hospitals into clean, more comfortable and effective facilities.

Miss Bucklin mentions “seven contraband women” who were helping with the laundry at this 13th Street hospital. Though not particularly complementary of their work, she does acknowledge that they had recently escaped slavery and may not have had the skills or domestic knowledge to perform their assigned tasks, a situation she quickly remedied by teaching, assigning, and working alongside the women. Many contraband—men and women—worked in the northern hospitals, doing their part to aid the Union.

And here’s an image of Hammond General Hospital, Point Lookout, Maryland. The prisoner of war camp is also in this illustration:

To be continued next weekend…

Thanks Saeah