Battle of Bristoe Station: A New Era in the Army of the Potomac

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Michael Shaara wrote in Killer Angels of the Army of the Potomac on the eve of the Battle of Gettysburg: it was the “last of the great volunteer armies, for the draft is beginning that summer in the North.” When that same Union army fought at Bristoe Station on October 14, 1863, it was a mixture of volunteers and conscripts.

The Confederate States of America resorted to conscription beginning in April 1862. Such measures were not enacted by the United States until March 1863. This later act stipulated that if districts did not meet their quotas by July, the Federal government would fill those quotas through a draft.

In the wake of the Union victory at the Battle of Gettysburg, several draft riots occurred in various Northern cities. The largest and most infamous of these disturbances took place in New York City in mid-July. Union soldiers fresh from the Gettysburg battlefield helped quell the uprising.

By the time of the Bristoe Station Campaign, some of the men drafted into the Federal army were beginning to appear in the Army of the Potomac’s ranks. Most of the newly arrived draftees meshed well with the volunteer veterans but in Alexander Webb’s 2nd Corps division, “the conduct of some few required on [Webb’s] part that measures should be taken to prevent misconduct and desertion.” Colonel James Mallon, a brigade commander in Webb’s division, appealed for help to deal with the new soldiers: “the conscripts recently sent to the Regiment [42nd New York Infantry] [are] suffering from want of [a] good drill master.”

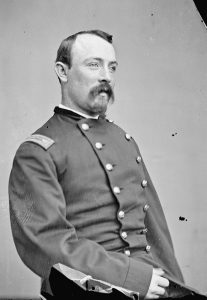

During the Battle of Bristoe Station, conscripts filled the ranks of much of the 19th and 20th Massachusetts and 42nd New York infantry regiments, among others. These three regiments were brigaded together under the command of Colonel Mallon. Confederate troops charged the Union position behind the railroad embankment of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad. Mallon’s 42nd New York held the part of the line where the Brentsville Road, today’s Bristow Road (Route 619), crossed the railroad, thus depriving the Empire Staters of the embankment’s protection. Charging Confederates temporarily broke the line and scattered the mostly conscripted New Yorkers. James Mallon leaped into this deteriorating situation to rally his soldiers until a Confederate bullet struck him in the upper body; he died within the hour. Mallon’s death was not for naught. Within minutes of the enemy breakthrough, the 42nd New York sealed the breach.

Farther to Mallon’s left, the 1st Delaware Infantry had 123 draftees in its ranks. As the Delaware soldiers charged towards the cover of the railroad embankment, one new soldier yelled to his comrades, “Gentlemen, they say substitutes won’t fight, but come on and we will show you!”

Despite this being their first battle, the Army of the Potomac’s draftees acquitted themselves well. Alexander Webb praised their efforts and relaxed his previous disciplinary measures against them. Mallon’s successor, Ansel Wass of the 19th Massachusetts, praised their conduct as “all that could be desired, and they showed themselves worthy to rank with the veterans of [their] regiments.” Nationally, newspapers applauded the conscripts. “I am here compelled to say a word of truth for the conscripts,” one correspondent told his readers. “Gen. Webb, who had a large number in his division, speaks of them in terms of wonder and admiration. They stood in their places and fought. No more can be said of the bravest modern warrior. They did more. They cursed—but it was because they could not load and fire as rapidly as our veterans.”

Bristoe Station marked a new era for the Army of the Potomac and the United States Army. No longer did jubilant volunteers or men with pockets full of bounty money entirely make up the ranks. The “last of the great volunteer armies” was now an army of both volunteers and conscripts.

I always thought that the number of actual draftees remained rather small, that the AOP still was largely composed of volunteers and substitutes, even in the Overland Campaign months later. Certainly the Bristle Station action shouldn’t be overblown as anything more than an appalling failure of Confederate reconnaissance, much like Iverson at Gettysburg.

It’s interesting how different conscription worked in States more solidly Union or Confederate, versus my home State of Missouri. I believe Mo was exempted from Federal conscription law, but had a compulsory State Militia edict in 1862. It forced loyal men between 18 & 45 to take an oath & enroll. Those who refused to take an oath were suspect, and many joined local guerrillas or went south to the regular CSA Army. Union authorities experimented in NW MO with unsworn militia to keep out Kansas Jayhawkers, but the so-called “Paw-Paw Militia” didn’t turn out well for the Unionists.

On his 1864 Raid, Price forcibly conscripted a few hundred men for Rebel service, many of them Germans. They mostly deserted or surrendered at first opportunity. Compulsory military service in contested areas might be a good & largely unexplored topic for a blog article!

Excellent follow up!