Surprise at Shiloh

The western battles of 1862 included three surprise attacks, although only one was planned as such. The opening Confederate attacks at Fort Donelson and Stones River caught the Union forces unprepared. Yet, neither caused a scandal, likely because both battles ended in decisive victories. Shiloh by contrast did lead to controversy because the Union forces had ample opportunity to know what was coming.

Tactically speaking, Shiloh was not a complete surprise. Everett Peabody’s morning scout had already engaged the 3rd Mississippi Battalion, and the Union had a picket line. When the battle began in earnest, the Rebels found fully formed battle lines waiting to receive them. That said, the Union rear forces were out of position and took time to form for battle.

However, Shiloh was clearly a strategic surprise. The day before the battle, Ulysses S. Grant informed Henry Halleck “I have scarcely the faintest idea of an attack (general one) being made upon us.” William Nelson’s division, part of Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio, had arrived and could have been sent over. Nelson even requested it, saying he was surprised the Confederates had not attacked Grant. Regardless of Nelson’s concerns, he would remain at Savannah across the Tennessee River.

In the Union camps, there were those who suspected something was afoot at Pittsburg Landing, but mostly they were regiment commanders and junior officers. Although two division commanders, John McClernand and Stephen Hurlbut, were concerned they were not on the front lines. Instead, William Tecumseh Sherman and Benjamin Prentiss commanded the foremost camps. Both men ignored the warning signs. Sherman told a nervous Jesse Appler, commander of the 53rd Ohio, “Take your damned regiment back to Ohio. There is no enemy closer than Corinth.” Prentiss refused to even speak with junior officers who had seen Rebel cavalry. In contrast to Grant, Sherman, and Prentiss, Private Jacob Fawcett of 16th Wisconsin felt certain a battle would happen on Sunday April. On the night of April 5 his friends gathered and one started to sing “with one accord…the songs of home and bygone days. Our last song was ‘Brave Boys are They.’”

The Confedrate plan was predicated on Grant failing to monitor the approaches to his camp, and the attack was conceived as a surprise. P.G.T. Beauregard advised Albert Sidney Johnston to retreat. Beauregard argued that the army had run out of rations, the attack had been delayed, and the Union had to know they were nearby. Beauregard thought Grant’s men would “be entrenched up to their eyes.” Johnston ended the debate with a flourish: “Gentlemen, we shall attack at daylight tomorrow.” As he left, he told his son, William Preston Johnston, “I would fight them if they were a million.” The battle was fought on April 6. Johnston died that day and Grant, bolstered by Buell’s men, was able to defeat Beauregard on April 7.

William Carroll, a member of Grant’s staff and reporter for the New York Herald, rushed to Fort Henry after the battle and submitted a fantastical report, in which Grant was not surprised and in fact led a heroic charge on April 7 that won the battle. Carroll wrote that Grant “brandished his sword and waved them on to the crowning victory, while cannon balls were falling like hail around him.”

Grant had been shrewd to court Carroll, and he was adept at exploiting the press. However, Whitelaw Reid’s report to the Cincinnati Gazette was more accurate and damning. Rumors of drunkenness soon followed and politicians called for Grant’s head, particular Governor David Tod of Ohio as well as Senator Benjamin Wade of Ohio. Tod said Grant and Sherman were guilty of “criminal negligence.”

Grant’s management of the army after Shiloh was poor. Hundreds deserted by stowing on steamers, spreading news of a near disaster. When a rumor spread of another Rebel attack, there was a wave of panic followed by more desertions. As at Fort Donelson, Grant had yet to learn how to manage an army after a battle. Morale was also low, with the soldiers generally blaming Grant for the near debacle at Shiloh.

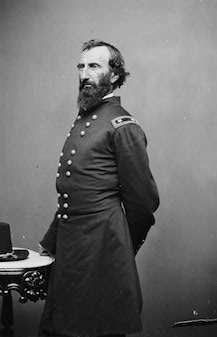

Grant survived Shiloh for a number of reasons. Abraham Lincoln did not want to remove him, supposedly saying “I cannot spare this man; he fights.” Yet, it is telling that Lincoln wrote him no letter of encouragement, and would not write him anything until after the fall of Vicksburg. After the fall of Corinth, he made the Army of the Tennessee a tertiary supply consideration; most of the new supplies and troops were sent to the Army of the Ohio and the Army of the Potomac. Lincoln toyed with replacing Grant with McClernand, and after the Holly Springs fiasco, he offered Grant’s command to Benjamin Butler. Although Halleck retained Grant, also seeing him as a good fighter, he considered Grant a terrible administrator. To be fair Grant’s staff was poor in 1862, something he even admitted to Simon Buckner after Fort Donelson fell. Halleck made little use of Grant in the siege of Corinth. When he went to Washington he brought John Pope, his favorite general at that time. When Pope failed, Halleck continued to bolster and promote his favorites in the west (Grant, Sherman, Ord, McPherson, Schofield, Sheridan) but no one achieved enough notoriety to be brought east until 1864. In the meantime, Halleck actively undermined McClellan, Burnside, Hooker, and Meade, and therefore the ability of those commanders to deal with Robert E. Lee. Such is the nature of command politics.

Every major battle of the Civil War generated controversy, but none quite like Shiloh. Debates have fluctuated over the years, but two things are clear. The Union army was not surprised in so far as they had battle lines formed. However, given the actions of Grant, Sherman, and Prentiss, the army was out of position and the high command was surprised. They were also lucky. Nelson had arrived on April 5, and on April 7 Buell would provide a total of four divisions of fresh infantry. If the attack had occurred on April 4, as Johnston and Beauregard had planned, the likelihood of a Union victory would have been much diminished with Buell’s men absent and surprise being likely; April 5 is really when Sherman’s and Prentiss’ men became alarmed. Grant, won Shiloh but barely remained in command. Had he lost he would then likely be remembered as a general who got lucky at Paducah, Belmont, and Fort Donelson. Such are the contingencies of history and memory.

There are several questionable opinions in this article:

-That Grant was “adept at exploiting the press.”

-That Whitelaw Reids report was accurate.

-That Grant’s management of the army after the battle was poor.

-That the date of Buell’s arrival had any significant effect on the chances of victory.

-That Grant was “lucky” rather than skilled.

The confederates failed to complete the job on the first day, and Grant had Lew Wallace’s un-bloodied division by the end of the first day. The confederate defeat was sealed at that point.

Grant had members of the press on his staff and befriended them. By the time of Vicksburg and Chattanooga he was adept at using the press to his advantage, unlike Buell and Meade, with Meade even humiliating one reporter right after Cold Harbor. At Shiloh Grant was still learning the ropes of press manipulation, but showing early promise. For example, while he was plotting to remove Thomas at Nashville, in front of the press he beamed with confidence.

Whitelaw Reid’s report was more accurate than Carroll’s report, which was pure fantasy. Thatsaid, Reid’s report had problems as well. To be fair, that is not clear in the text.

That Grant’s management of the army after both Fort Donelson and Shiloh was poor. In the case of Shiloh he failed to contain desertions or noticeably improve morale, organization, and even defensive positions. Supplies were also not quickly forwarded; soldiers letters go on and on about the encampment being misrable after April 7. That said, by 1863 Grant’s staff and army management had improved quite a bit.

Buell’s arrival meant Grant could deflect any attack Beauregard might have made and more importantly allowed both him and Buell to attack on April 7. The most important factors in Union victory were terrain, Buell’s 15,000 troops, and the Confederate’s inability to attack on April 4 or 5, before the bulk of the Army of the Ohio had arrived. Without Buell, the battle would have been much closer, and given the number of deserters both during and even after the battle, I give the edge to the Confederates. Their morale on April 6 and even until roughly noon on April 7 was sky high. Buell was not a good general allaround, but Shiloh was his moment.

Grant had skill which allows one to make the best of fortune when it comes your way and to handle misfortune. That said, I have never read of a successful commander who did not have some luck go their way. My point is if Grant had lost Shiloh or even died, he would not be remembered the way that he is remembered today by his fan club, which is as the preeminent military genius of the war and possibly all of American history. Instead, he would be seen as lucky for barely escaping Belmont and for having Confederate commanders at Fort Donelson who squandered a victory gained.

For the record, I think Grant’s finest hour was Fort Donelson once he returned from his meeting with Foote. At Shiloh he was good during the battle, less so before and after.

I disagree, but have seen similarly skewed arguments in the recent anti-Grant books. In my opinion, no modern author has done a better job writing about Shiloh than Timothy B Smith. Very well written books and no overt bias. I’ll stick with his scholarship.

Sean, you stated that “Grant had members of the press on his staff and befriended them.” I knew Rosecrans had a Cincinnati journalist on his staff but I had not heard that Grant had a journalist on his staff. Can you give a name or names? Thanks.

Grant had at least two reporters serve on his staff: Willliam C. Carroll at the Battle of Shiloh as a voluntary aide and Sylvanus Cadwallader served for a much longer period as a de facto aide.

I don’t remember seeing any evidence that Bickham was on Rosecrans staff, although he was certainly around Rosecrans’ headquarters.

Among the Grant fans, Smith is the best because he is more honest about his failings, such as his poor staff work at Fort Donelson, mistreatment of McClernand, and how Carroll’s report damaged Grant’s standing after Shiloh.

Smith is helping me a bit with Maps of Shiloh for Savas Beatie. We agree and disagree on some points, particularly Buell’s contribution to the victory. Its the nature of the work.

The problem with Grant is that people seem to fall into anti and pro factions, and both sides are convinced the other is biased. I fall mostly between the two, so I draw fire from both, but mostly from those who have made Grant the new “marble man.” I think it is because I will point out his failings, which is far more than most of his fans are willing to do.

I don’t agree that Grant is considered the new “Marble Man” except by those with a bias against him. Grant’s biographers include just criticism of him. Read Simpson or Chernow.

I heard a story about Eric Wittenburg, where he was asked if he would write a biography of Phil Sheridan. Wittenburg said no, that because of his personal dislike of Sheridan, he would not be able to be fair.

It would be nice if the anti-Grant writers would follow his example, and write about history they can approach with a certain degree of objectivity and positive interest.

I have read Simpson and Chernow. Simpson is far better in my opinion, and along with Smith, the best of the Grant fan club. I like The Civil War in the East

Biographies almost always fall into either hagiography or hatchet job. Its the nature of the best. If you write about a single person, it is usually due to attraction or repulsion. Wittenburg did not write a full scale biography of Sheridan, but he did write about him in Glory Enough For All and extensively in Little Phil, which is a kind of Civil War biography. Can these books be trusted due to bias? Perhaps it is best to read them since most other books are unreserved in their praise of Sheridan.

The issue with the pro vs. anti factions is that certain people in each are unwilling to answer the arguments of the other side, and sometimes ad hominem attacks are deployed.

Being in neither faction, I have no stake in the deification or vilification of Grant, and I have argued with members of each faction. I do wish though that certain elements of the pro faction would not take every criticism of Grant as an excuse to denigrate contrary scholarship and opinion. Grant and Lincoln though are the “heroes” of the war, and so criticism of them is treated with more derision than it is of Lee or Sherman. Of Lee, there are historians of the last 30 years who treat him as semi-incompetent. It is as ridiculous as the old “Grant the butcher” myth, and each is used to advance certain partisan narratives about the war.

Brooks Simpson, on his old blog, once stated that Grant was a survivor (this implies some good fortune and timing) in contrast to Rosecrans. Sean’s basically making the same point here. I agree with both of them. Grant’s career could have been snuffed out on any number of occasions.

Good point about being a “survivor”. After Belmont; after Shiloh; summer-early fall 1862; during the initial series of attempts at Vicksburg. The same “trait” may have served him well in battle.

I’m not sure I’d include Tim in a “fan club” – as opposed, perhaps, to some others you name. One can debate Grant’s accomplishments or failings without necessarily being pigeon-holed as a “fan” or “anti-Grant”.

I have no problem with criticism of Grant or Lee if it is accurate. Unfortunately, much of the “contrary scholarship” is so affected by bias as to be more fiction than fact.

You represent yourself as without bias, but I think your terminology “Grant fan club” in relating to Grant biographers illustrates your own bias. Grant writers are really not in diametrically-opposed camps. Some Grant writers have approached their subject with more objectivity and professionalism than other writers. They include criticism as well as praise, when applicable.

I’m no scholar of Grant or Lincoln, but I’m hard pressed to not label Grant a butcher after Cold Harbor. In the name of saving the Union, Lincoln played fast and loose with the Constitution. They are viewed more favorably because the Union won the war. Had it not, Grant would have probably been court-martialed, and Lincoln would have been impeached.

Being a Southerner, that’s my biased viewpoint!

I think in the club so to speak, Smith, Simpson, and to a lesser degree Laver have been the most honest about failings, although each is very much an admirer of Grant’s generalship and personality. Unfortunately, Bonekemper, Woodworth, Chernow, Waugh, White, and Flood are less honest about those failings. I do credit Chernow for taking the alcoholism seriously. It makes Grant more impressive. He was a success in spite of his weakness.

In the anti-Grant club, McFeely also has good things to say, even if he is not wholly positive, so I like him best in that faction. Leigh reads like he has a snarl and Rose goes overboard, although he is a good man to debate and is helpful.

I do have a bias because we all do, I am just not in either club in terms of Grant. I likely fall between Smith and McFeely. I just find certain members of the “fan club” are too willing to defend every Grant error and sadly too willing to dismiss other scholars out of hand.

These are fair points regarding how a lot of authors line up on Grant. I’m not sure I’d list some as being properly included in the “club” (as opposed to others). As for Rose in particular, the research is prodigious but at some point his work went from objective historical analysis to a legal brief in the case of Rose v. Grant. After reading his book one cannot imagine how the Union managed a win with this bumbling, drunken, petty, vindictive, tactically inept failure at the top. As you suggest, much of it is good for debate/discussion but it almost makes Nolan’s book on Lee look bias-blind. At least Nolan was a lawyer so there’s that.

I’ve never understood why Grant – who conceded in his Memoirs that Cold Harbor was a mistake – could never admit to being surprised on April 6. He clearly was. That’s easily demonstrated by how he aligned his divisions – especially the locations of the raw troops under Sherman and Prentiss; keeping Lew Wallace up at Crump’s; staying downstream himself at Savannah rather than at Pittsburg Landing; and the complete absence of any minimal defensive precautions in his camps. As for Shiloh being Buell’s “moment”, he really didn’t do much beyond contributing his additional troops (which did play a key role on April 7). That’s positive but hardly required any sort of brilliant generalship. And he falsely claimed the concept of establishing Webster’s final line at PL. Shiloh was probably the best moment in his mediocre Civil War career – certainly compared to his ineptitude at Perryville – but that’s a low bar.

I have spoken to Rose about some of the above, and his answer was it was meant as an expose, hence the subtitle. So it is a case of throw everything at it and see if it sticks on the wall.

“After reading his book one cannot imagine how the Union managed a win with this bumbling, drunken, petty, vindictive, tactically inept failure at the top.” – This ties into Rose’s larger point about Grant. The North could have won without him, given their material superiority, willpower, and the relative quality of its commanders. On the latter point I certainly agree. Thomas, Rosecrans, Sherman, Hooker, Meade, and Sheridan were all capable and successful. I doubt America could have beaten Britain without Washington or Mexico without Scott, but on Grant I am not so certain. Lincoln seems the more indispensable man.

I agree with Rose that Grant was petty and vindictive, but I admire him as a strategist and master of operational maneuver. Rose thinks his ability to cultivate the press and play army politics was a weakness. I see it as a strength, even if it had a darker side in relation to men such as McClernand and Rosecrans.

I won’t use “club” anymore as it is inaccurate. Perhaps, consensus is better? Certainly Grant’s current reputation has not been this high since the 1880s-1910s.

I think that’s a fair substitution for “club”. My problem with Rose is that i’ve never seen him concede the bias element – not just in the book but on his blog site. The research – again, “prodigious” – actually creates the impression of objective analysis. Yet one can find inevitable “choices” or “interpretations” at the micro level which go in one direction. The treatment of certain Grant “victims” – McClernand and Rosecrans come to mind – is far from even-handed. As for your broader point, we’ll never know how the options would have worked out. I’m extremely skeptical of Hooker, who allowed himself to be defeated by an enemy he vastly outnumbered and whose weaker forces were also split. Meade did a nice job of defending with little notice at Gettysburg but the pursuit, Bristoe, and Mine Run were hardly advertisements for success. Sheridan? Maybe, although that would be based on one campaign. Rosecrans did well in Tullahoma but Stones River was no gem and Chickamauga was a debacle. Sherman and Thomas? Maybe. For all of his mistakes, Grant did pull off Henry/Donelson; did at least respond well at Shiloh; did figure out a way to maneuver and take Vicksburg; and ultimately did lead the Federals to victory. Personally, I try to evaluate this by looking at the Wilderness after Day 2. For whatever reason Grant’s decision to keep trying to turn Lee after suffering what could be labeled a tactical defeat – or something close – is not something I can readily see from the others. Getting up off the floor for another punch is not necessarily a sign of “generalship” but it played a significant role in the success of a general who caused three armies to surrender. And I for one can recognize Grant’s not unimportant deficiencies but it’s hard to minimze what he ended up accomplishing.

Hooker and Meade had a major problem in Henry Halleck, who actively undermined both of them. I think Sears is right that Hooker lost Chancellorsville because of a concussion. In pretty much every battle he was first rate. He certainly did not “lose faith in Joe Hooker” as Doubleday averred.

Meade’s post-Gettysburg pursuit is understandable. His army was shot up, with very high officer losses, including his two most trusted corps commanders. Lee’s defensive position at Falling Waters was nigh impregnable. After Gettysburg Meade was stripped of troops and ordered by Halleck, Stanton, and Lincoln to carry out a faulty strategy. The true line of operations was the James River. Meade, Grant, McClellan, and nearly everyone in the army knew it and it was the line where Lee was ultimately defeated, even if it took a very long time with a very high body count.

Mind you, Hooker and Meade made mistakes, but they had political disadvantages and were undermined in ways Grant rarely was, which goes back to my praise of his political shrewdness. Grant could keep going because he had the full backing of the Lincoln administration. He could and did call on reinforcements, something that was denied to McClellan, Hooker, and Meade when they asked for it. I will concede that McClellan would not have kept going on after a defeat like Wilderness; his strengths were strategy, logistics, charismatic leadership, and engineering, but he was not a fighter.

Of Rosecrans, I do consider Stones River an impressive victory, but I do think the Grant “haters” are too quick to excuse him. I guess it is human nature. At any rate, Kiper’s McClernand biography is about as fair a book as I have ever read in a genre known for hagiography and hatchet jobs.

No question that Halleck was a negative factor overall. But Chancellorsville cannot be laid entirely on the concussion/inept subordinates/bad communications luck, etc (as Sears does). For one thing Hooker had brilliantly gotten a large jump on Lee and then dropped the initiative beginning on April 30, dictating that his end of the fighting would take place in, and not beyond, the Wilderness area. As for Sears’ excuses, at some point the list just becomes too long. The buck stops at HQ. By the time he was concussed Hooker’s plans were already in the waste basket. Regarding Rosey, we probably can agree to disagree about how well he fought Stones River (even aside from the cost he expended to get there). Things were in dire straits on the first day. I do, however, agree on the Kiper bio. At bottom McClernand was a self-aggrandizing politician but Kiper’s book is the sort of balanced analysis we need.

Rose is a devoted fan of General Thomas and the Army of the Cumberland, and apparently let it fuel an obsessive resentment of Grant. I have his book and it is truly bad. It’s more spin than an accurate attempt at writing history.

I don’t think any of the generals you mentioned were capable of doing what Grant did. Particularly not Thomas, who preferred being a subordinate. McClernand and Rosecrans were not innocent victims. They did their own conniving and playing politics and courting the press.

That Grant’s reputation has risen is not a good or bad thing. Getting the history right is the important thing, and I think John Simon’s massive effort with the Grant papers helped the modern authors significantly.

I think Thomas, Rosecrans, and the Army of the Cumberland were underrated for so long that some recent scholars have over-compensated, which is also the case with Grant too. I can say from talking to Rose his work did not start from a love of the Army of the Cumberland, but rather by noting inconsistencies in Grant’s memoirs and how certain scholars were using the sources. He then went about collecting a lot of information; few scholars have done as most archive hunting as Rose.

The way I use Rose in my work is to read his arguments and then try to answer yes of no to what he is arguing. On Shiloh we disagree on Grant’s battlefield actions once he landed, his role in setting up the last line, and on whether Grant had to use crutches. Rose does not understand that tactically Grant was not a micromanager, and that is not a bad thing either.

Thomas wanted his own army command, he was just not comfortable with politicking. Considering Thomas’ use of combined arms at Nashville and his pursuit through horrible weather, he could have done what Grant did, at least in purely military terms. He was certainly the better pure tactician. However, his political skills remain a question mark. He also maintained his friendship with Rosecrans, which made him suspect to Grant, Stanton, and Halleck, although after Nashville Stanton became Thomas’ biggest supporter along with Sherman.

Grant did not do right by McClernand and to a lesser degree Rosecrans. McClernand publicly and privately supported Grant until the siege of Corinth, even after Grant started to detest him. Once McClernand could see that he was not able to win over Grant or Halleck, he understandably turned against them; what else was he to do? Grant downplayed McClernand’s success at Fort Hindman, his role in taking Vicksburg, and fired him in the most humiliating fashion. Of Rosecrans, Grant took credit for Iuka and thought his victories at Corinth and Stones River were not important, even telling that to Lincoln, during their last meeting. He also fired Rosecrans in a humiliating fashion. That said, Rosecrans did little to repair their relationship after Iuka, and he could be a difficult subordinate. I will say, in terms of Grant’s feud with Prentiss, I side with Grant generally.

As for “Getting the history right” it will never happen. Attitudes, perceptions, and concerns change, and history is so complicated that one can draw different conclusions. My overriding issue with many scholars is that they pick their favorites and the ones they detest and go from there. In the case of Grant, a lot of personal and professional failings are ignored or downplayed. Yet, because they are there, I can see his reputation declining again at some point. John Simon’s papers alone provide a lot of ammunition. Just take Belmont. Grant lied about why he went there, argued that his force was not routed, and then had Rawlins write an error ridden report in 1864 that was back dated to November 17, 1861. The original report is gone. Simon confirmed all of that in his work.

That Grant was a talented commander is clear, but he was not the humble and honest man that he is so often portrayed as. He was a good family man, and loyal to friends (maybe too loyal), but he was spiteful to those he saw as rivals, both real and imagined.

How Grant is viewed in 50 years will be different and it is the name of the game.

Where on earth did you come up with this nonsense that Thomas wanted to be subordinate? He came back to life and told you? You read it in his papers? LOL It’s simply a trope trotted out to excuse Grant from his nepotism in putting Sherman (who at that point had little to his credit and had botched his big moment at Chattanooga bigly from start to finish) in charge in the west over the Rock of Chickamauga (who had done nothing but excel at virtually every point in the war). I suggest that you drop that silly line of argument, there’s not a shred of evidence to support it.

On the matter of Shiloh, most generals are proud men who wish to improve their reputations. Grant and Buell were not modest men, and they had tension going back to the capture of Nashville. One has to read them with that in mind. Certainly Buell did not set up Webester’s line, while I do not believe Grant’s contention that Buell ever intended to retreat. His actions on April 6 do not suggest a man willing to back down.

I just read about Belmont, and Grant argued that his force was not routed. The evidence to the contrary is massive. On the Confederate side Pillow made it seem like he grabbed victory out of the jaws of defeat. While Pillow was not a coward at Belmont, he certainly lost control of things and placed his men in a poor position. However, each man had a reputation to maintain.

I think that two distinct issues tend to get commingled: (1) the accuracy of Grant’s memoirs; and (2) Grant’s actual performance and that of others he was on the ‘outs” with. Buell is a good example. On April 7 there is little doubt that the additon of most of Buell’s forces (ironically without his best division commander) were essential to driving the Confederates. On the other hand from a tactical standpoint they did not turn in an A-1 performance. Ironically the key tactical achievements were probably from one of Grant’s divisions – ironically, that of Lew Wallace (twice). So any suggestion that Buell’s Army of the Ohio was extraneous to what happened on April 7 is fallacious. So is any notion that Buell turned in some sort of masterful performance. I also strongly question whether the Confederates would have broken Grant at the PL line with or without Buell or that Buell “saved” Grant – which are completely different from whether Buell was essential to the next day.

I would not call Buell masterful as Shiloh. He failed to coordinate with Grant and tactically his forces did not smash the Confederate flank. However, it is his moment because he brought in the men that made Union victory a near certainty and he launched the main attack on April 7. As noted, I also do not think Buell advocated a retreat.

Of all of his services to the Union, Shiloh must rank as his best, not through any act of genius, but simply by being present with 15,000 men and the will to fight.

That’s fair. I think we agree. If anybody deserves accolades in the Army of the Ohio, maybe it’s Bull.

“How Grant is viewed in 50 years will be different and it is the name of the game.”

Some historians and biographers stand the test of time better than others. Bruce Catton, for example.

But you’re right that the view of the Civil War, and the assessments of its commanders will continue to evolve. I have my own predictions of which reputations will decline.

There is a lot here for discussion.

Strategically speaking, as Sean noted, Shiloh was a complete surprise. This occurred because Grant (and Sherman) failed to use spies, scouts, patrols, vedettes, or prisoner interrogation to determine the location and designs of the enemy army. They ignored the obvious signs of imminent attack.

Tactically speaking, it still was a surprise, although lessened because of Peabody’s proactive advance, even if there were “fully formed battle lines.” The camp’s tents were still up and the regiments’ sick were still in them; ammunition for the battle had not been distributed; some soldiers had not breakfasted, artillery was not emplaced; large gaps existed; the men and officers were not psycholgically ready; there was no overall commander until Grant arrived at 9:30; etc. My exposé details all of these failures. Try to find a proper discussion of these criticisms in Dr. Smith’s Shiloh: Conquer or Perish. At one point, he goes so far as to conclude that, if there was a tactical surprise at Shiloh, it wasn’t the Confederate attack on the morning of April 6th, but McClernand and Sherman’s counterattack around 12:30 pm. That is absurd.

Dr. Smith, who should have a fine knowledge of Shiloh, is so pro-Grant he erroneously writes that Grant’s morning messages from Savannah told Buell “to send his arriving troops on up the river as quickly as possible” and told Wood and Thomas “to hurry forward.” At Crump’s, Grant supposedly told Lew Wallace to ready the 3rd Division to march southward. No, it was in any direction. Smith even argued that “the attack caught even the Army of the Ohio by surprise,” which is a misuse of the concept.

Others who denied surprise include Grant’s and Sherman’s supporters: Adam Badeau, S.H.M. Byers, Henry Halleck, William S. Hillyer, George P. Ihrie, Mortimer Leggett, Basil Henry Liddell Hart, Thomas Livermore, James B. McPherson, Charles Moulton, John A. Rawlins, Albert D. Richardson, William Rowley, Israel Rumsey, William Sherman, Joseph Ware, James Harrison Wilson, and Grant himself.

In my opinion, those who deny the enormity of this surprise can be termed “pro-Grant.” As to Bruce Catton, I state in Grant Under Fire that: “He replaced the perfectly correct conclusion in Mr. Lincoln’s Army, that ‘Grant fought the battle of Shiloh—fought it inexpertly, suffering a shameful surprise, losing many men who need not have been lost,’ with a tortured defense in Grant Moves South, which admitted little more than that Grant and Sherman erred in responding to accusations of a complete surprise.”

I’ll stack my research against the typical pro-Grant position that denies or minimizes the Shiloh surprise.

With all due respect this demonstrates the problem with affixing simplistic labels. You fail to acknowledge that Tim Smith also stated that Shiloh was a strategic/operational surprise and the notion of Grant being “surprised” appears elsewhere in his book (as it does in his many other publications on the battle). Smith does assert that it was not truly a tactical surprise, which is at least fairly arguable. Front-line units did respond and Johnston’s attack did not proceed unimpeded as did Jackson’s at Chancellorsville. Smith does not attribute this to Grant’s efforts but to those at the front. Smith also states quite clearly that Grant did not “manage” the battle on April 6 but confined himself to rallying attempts. As for the meeting at Crump’s Smith has Grant telling Wallace to hold himself in readiness to move south (the direction from which both could hear the firing) but to await orders and to watch his own front. It may be inconvenient that an author doesn’t neatly fit a pejorative label but that’s the role of nuance and good analysis.

Mr. Foskett,

Transcriptions of his book from CivilWarTalk, assuming that they’re accurate, show a repeated pattern of Dr. Smith’s denying or minimizing the surprise. He wrote: “Thus, the Federals had several minutes in some cases and hours in others to sound the long roll, form their lines, and take positions to defend their encampment….” making it seem as if this were sufficient to negate the effects of the surprise.

Similarly, he apparently wrote: “As a result, when the slow and plodding Confederate advance began to approach the Union camps around 7:00 a.m., they did not find sleeping and surprised Federals who offered little resistance. Rather, they found regiment after regiment with artillery batteries in line, ready and waiting to meet them.” The Confederates, however, did find “surprised Federals” and several regiments “offered little resistance.” Again, Smith’s writing hides the lack of Federal preparedness.

And akin to Smith’s absurd suggestion that “if there was a tactical surprise at Shiloh, it wasn’t the Confederate attack on the morning of April 6th, but McClernand and Sherman’s counterattack,” Dr. Smith argued, “In that sense, Shiloh was no surprise, except perhaps to the Confederates who expected no such reception.”

It is not “fairly arguable” to assert that Shiloh “was not truly a tactical surprise.” The reason an army attempts to surprise the enemy’s forces is to catch them unprepared. Grant’s forces were seriously unprepared for battle and nearly lost it as a consequence. Dr. Smith does not discuss this in any substantive way.

Yes, Smith stated that Grant did not “manage” the battle on April 6 but confined himself to rallying attempts. He further told me that Grant stayed behind the lines for most of April 7, as well. But he still concludes that Grant deserved great credit for the victory. Grant’s generalship during the battle, in my opinion, did not make up for his failures to prepare or to prevent surprise.

At Crump’s, Grant told Wallace to be ready to move in any direction, so Smith is wrong in asserting that Grant told Wallace to hold himself in readiness to move south. Forget about Grant’s failure to have Wallace move south around 9:00 a.m. or to have the steamer, John Warner, keep descending to Crump’s to order Wallace to do so, once Grant had been informed that the battle was upstream.

Any good analysis of Smith’s books (and I can provide many more examples of his prejudice) shows that he makes many factual mistakes and frequently uses rather tortured reasoning, both almost always in Grant’s favor or neutral, at best. Have you found any instances where Smith was too hard on Grant? How could he have written that Grant’s morning message told Buell “to send his arriving troops on up the river as quickly as possible,” when we have the text of this message and it says no such thing?

P.S. It is not incumbent upon me to “acknowledge that Tim Smith also stated that Shiloh was a strategic/operational surprise.” He certainly got much correct in his history of the battle.

Mr. Rose: I’d read the book before pinning a label on the author. As i pointed out, there are multiple references to Grant being caught by “surprise” in the book.

Regarding what he told Wallace at Crump’s, you appear to be relying on Wallace’s 1896 account as the authentic, verbatim version. As I’m sure you are aware (or should be), Wallace’s various renderings of Shiloh after Grant’s death are suspect in several instances and demonstrably false in others (for example, his assertion that on April 4 he transmitted to Grant a scout’s warning that Johnston was marching on Pittsburg Landing. If needed, I can give you the multiple layers of evidence establishing that it’s a fabrication.) In addition, the Smith account of the directive is not materially different. The sounds of battle were coming from the south. In fact Wallace apparently expected an order to head that way. According to Smith Grant told him to hold off, to be ready to head that way, but to also watch his front in the direction of Stony Lonesome. Attacking Smith because he didn’t literally adopt Wallace’s version (three decades later) verbatim snacks of looking for an angle. Rather than spending further and excessive bandwidth, I hardly find Smith’s multiple references to surprise and his statement that Grant did not “manage” a battle in which his army was in desperate straits to be indicia of membership in a fan club.

P.S. Frankly, I think it is incumbent on an author who is being objective and who values credibility to point out that Smith clearly acknowledged strategic surprise. You raised the subject in a post directed at labeling an author as part of the Grant fan club. Carefully referring to Sean’s point and ignoring the fact that Smith did the same is disingenuous.

I’ll address your other observations shortly.

My style of research is to gather as much significant information as possible and, after weighing the reliability of the various sources, try to determine what actually happened. As to what Grant told Lew Wallace at Crump’s Landing while ascending the Tennessee on the morning of April 6th, I do not have to rely on Wallace’s 1896 version.

Grant wrote McLean on 4/9/62 (in OR 10:1:109) that, “General Lewis Wallace, at Crump’s Landing, 6 miles below, was ordered at an early hour in the morning to hold his division in readiness to be moved in any direction to which it might be ordered.” He reiterated this on April 25, 1862 (in PUSG 5:68): “I directed this Division at about 8 O’Clock a. m. to be held in readiness to move at a moments warning in any direction it might be ordered.”

As both participants in the conversation agreed on this point, I can assert that Dr. Smith was wrong in claiming that Grant told Lew Wallace to ready the 3rd Division to march southward.

In the same message, Grant then claimed that, “At about 11 o’clock the order was delivered to move it up to Pittsburg, but owing to its being led by a circuitous route did not arrive in time to take part in Sunday’s action.” Although on one page, Dr. Smith wrote that the orders going from Grant to Rawlins to Baxter to Wallace “could have said anything,” he somehow knew (on another page) that Grant’s message to Lew Wallace ordered him to march to Pittsburg. Now, here is where my research provides better history than merely taking Grant’s word on an issue.

My book, Grant Under Fire, details the consensus on the desired destination in Grant’s order:

• After being passed around, the unsigned note was subsequently lost by one of Wallace’s staff. That mattered little concerning the Third Division’s destination, as it was assuredly Sherman’s right flank. Lew Wallace and four of his subordinates identified the orders’ stated objective as the right of the army, denoting Sherman’s right. Baxter remembered giving Wallace instructions “to march his command at once by the river road to Pittsburg Landing, and join the army on the right.” As the writer and deliverer of the message and its recipients all agreed, additional corroboration was redundant. But on the first day of battle, Grant informed McPherson, according to the engineer, that Baxter’s orders referred to “a position on our right.” Sherman’s autobiography related how Grant told him, during their first meeting around 10:00 a.m., that he ordered Lew Wallace’s division “to come up on my right,” which at that time was near the Owl Creek bridge on the Hamburg-Purdy Road. Rowley, shortly after noon, rode to Wallace with Grant’s instructions to “form his division on the extreme right.” [Paragraph] Whitelaw Reid reported the general understanding that in an attack, Lew Wallace’s Third Division “was to come in on our right and flank the rebels by marching across from Crumps’s Landing below.” In 1868, Grant stated that his orders “were substantially as given by” biographer Badeau, who had written, “Lewis Wallace was directed to come up and connect with Sherman’s right.” Of the two participants who suggested a different destination, Rawlins remembered it being “in rear of Smith’s divisional camp,” but still described it as “on the right of our lines.” Except for one unsubmitted report written after the battle that coincided with Rawlins, and was probably drafted by him, Grant stubbornly insisted that his verbal orders were for “Pittsburg Landing.”

By taking Grant’s unsupported claim, in the face of overwhelming evidence, Dr. Smith shows himself to be a pro-Grant partisan.

Until now we were focused solely on what Smith said the order was at Crump’s at 9 AM. The two versions are a “distinction without a difference”. Ready to move in “any direction” would include south and west (Stony Lonesome, where Wallace’s division was). In Smith’s interpretation Grant covered both (I doubt that even Wallace thought he might have meant north or east – the latter would have required boats). The whole point – right or wrong – was to wait for an order until Grant sorted out what was going on. Smith has never said – anywhere – that Wallace was ordered to head south before the 11-11:30 AM time frame when the entire Baxter/Rowley/McPherson controversy started.

You’ve now expanded the question and you’re commingling the two different sets of orders, which is misleading. Regarding the Wallace controversy, in the book Smith refers to Grant’s staff as a “public relations department” which got the entire controversy wrong as to Wallace. I’m puzzled as to how that puts him in some sort of blind fan club.

In short, you still haven’t justified the label you affix to Smith. That might be acceptable in an opinion-driven blog site but not as a matter of objective analysis.

By the way, as I’ve said many times, your research is undeniably extensive although I disagree with some of the conclusions. One thing that has always puzzled me are your qualifications. I can find them nowhere and I know that this may have been a factor in an erroneous review of you book a few years back. It’s not customary for an author – especially a new one – to publish a book without providing some credentials. No requirement to do so, of course, but it might prove enlightening.

Another element of Grant’s orders to Lew Wallace (which were likely relayed verbally through Captain John Rawlins to Baxter to Lew Wallace in an early form of the game Telephone Line) is that after receiving them Major General Wallace asked Baxter about “the state of the battle,” and Captain Baxter replied, “We are driving them.” Not holding on; or falling back towards the Landing. But pushing the enemy away.

Also it must be considered that in the weeks leading up to Shiloh, while Smith’s (afterwards Grant’s) Army was accumulating at Pittsburg Landing, Savannah and Crump’s that a major threat was posed by the north-south line of the Mobile & Ohio Railroad, just a few miles away to the west. Confederates had ability to quickly transport a sizeable force north from Corinth and launch an attack from that railroad (which until 6 April 1862 was considered most likely against Crump’s Landing.) In period writings, William Tecumseh Sherman records his position three miles west from Pittsburg Landing as facing West, towards that railroad threat. In other reports, Sherman indicates his division, sited at Camp Shiloh, faced south towards Corinth. But regardless, the Right of Sherman’s Division remained three miles away from the steamboat landing at Pittsburg (and could only have been sited AT Pittsburg Landing if Sherman’s Division faced North, which Sherman never claimed.)

In effect, the circuitous march of Lew Wallace took place because of the orders themselves, issued by Major General Grant to Major General Wallace. Grant assumed he included elements in those initial orders that he did not. And he afterwards asserted that those elements (in particular, for Lew Wallace “to march to Pittsburg Landing”) were specified in the orders, when they were not.

Mike Maxwell

The phrase “come up on my right” does not necessarily mean come from the direction of 90 degrees to my right. And seriously, Whitelaw Reid as a source?

If it is problematic for Smith to assume he knows Grants exact words to Wallace, then it’s equally problematic for the Grant haters to assume they know the exact wording of the order to Wallace.

I’ll stick with Timothy Smith, thanks. His books are very well regarded. If he has any bias, it’s at least not a crazy bias like the anti-Grant crowd.

There are many assertions in the Shiloh section of the Rose book that are simply wrong.

Rose describes Wallaces orders for the advance on the second day as “scanty and maladroit” and then proceeds to write a fictional account of Wallace changing directions on his own and Grant showing up to correct his course by directing him toward the “swamps.”

In fact, Wallace admits in his autobiography that he himself had drifted off course and the direction that Grant re-set for him in the afternoon led him to arrive in Shermans camps of the prior morning, not the “swamps.”

Also, Rose claims that in the memoirs, Grant “went so far as to claim that the Army of the Ohio only arrived after the shooting stopped.” This is false. There are references in the memoirs to the shooting that was still occurring after Army of the Ohio arrived.

Rose criticizes Sherman for personal statements about Shiloh that conflicted with his account in his official report, but Rose includes a very negative Hurlbut letter to his wife about Shiloh without noting that Hurlbut’s official report sounded completely different.

Rose claims that Shiloh “represented a major strategic defeat” for the Union. This view fails to understand Hallecks stated strategy objectives.

The Timothy Smith book is far and away more credible and authoritative on Shiloh.

Yep – major strategic defeat? Johnston was dead; his army failed in its mission; Buell successfully joined up with Grant and then Pope came on board; and ultimately the Confederates had to give up the rail hub of Corinth (which they desperately tried to retake, without success, in October).

General Grant in his Memoirs on page 278 states: “I never could see, and do not now see, why any order was necessary further than to direct him to come to Pittsburg Landing, without specifying by what route.”

However, something unexpected happened, even before General Grant commenced writing his Memoirs, the fruit of which ended up in Grant’s lap after he had written the above statement. A former Confederate soldier living in Georgia (M. R. Tunno) had been organizing his wartime papers sixteen years after Shiloh and ran across a document he’d forgotten he had: a brief memo he’d found on April 6th 1862 in a dying man’s pocket from Major General Lew Wallace to Brigadier General WHL Wallace, acting commander of Smith’s Second Division. In the memo, Lew Wallace directed that: “I will tomorrow order Major Hayes of the 5th Ohio Cav to report to you at your quarters; and if you are so disposed, probably, you had better send a company to return with him, that they may familiarize themselves with the road, to act, in case of emergency, as guides to and from our camps.”

Finding the above memo, and realizing its potential significance, Tunno wrote a Letter dated 9 June 1878 to the Governor of Illinois requesting that “the package of effects [enclosed] be delivered into the hands of the Family of General Wallace” [details contained in Life & Letters of General WHL Wallace pp.215 – 218 and 188 (Memo).]

On June 28th 1878 Judge Lyle Dickey wrote his daughter, Ann Wallace, of the receipt of her husband’s effects via the Governor of Illinois. And Mrs. WHL Wallace subsequently took possession of those effects. And in 1885 while General Grant was in process of completing his Memoirs, Mrs. Wallace sent a copy of the 1862 Memo from Lew Wallace to WHL Wallace, believing it may be of some use to General Grant.

Upon review, General Grant wrote the following (Memoirs p.289 Note): “Since writing this chapter I have received from Mrs. WHL Wallace… a letter from General Lew Wallace… At the date of this letter it was well known that the Confederates had troops out along the Mobile & Ohio Railroad west of Crump’s Landing and Pittsburg Landing, and were also collecting near Shiloh. This letter shows that at that time General Lew Wallace was making preparations for the emergency that might happen for the passing of reinforcements between Shiloh and his position, extending from Crump’s Landing westward; and he sends it over the road running from Adamsville to the Pittsburg Landing and Purdy Road. These two roads intersect nearly a mile west of the crossing of the latter over Owl Creek, where our right rested… This [Letter and its contents] modifies very materially what I have said, and what has been said by others, of the conduct of Lew Wallace at the Battle of Shiloh…”

[Full history and contents of this exchange contained in references sited.]

Mike Maxwell

Excerpts of Dan’s original comments are in brackets

[Rose describes Wallaces orders for the advance on the second day as “scanty and maladroit” and then proceeds to write a fictional account of Wallace changing directions on his own and Grant showing up to correct his course by directing him toward the “swamps.”]

As to the orders to and movements of Wallace’s division on April 7th, Grant provided Wallace with no maps or guides, but left him severely on his own, apart from two terse orders. There is no doubt that in post-battle accounts Wallace repeatedly described Grant as providing almost no information. Both orders had Wallace advancing in a westerly direction toward the swamps of the stream.

From Wallace’s testimony to the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War 1863 Report Part 3 [Pg. 342] “He gave me the simple direction to march forward with my command, in a direction that was directly at right angles with the river. That was about all the order I received. … if I persisted in going forward in the direction I was then going, I should find myself and my whole command in this almost impassable bottom of Snake creek. I was not disposed to go there. I saw a chance, as I thought, of turning the enemy’s left flank. I accordingly changed the direction of my command by a left half wheel, and we pushed forward.”

From Lew Wallace’s Autobiography, Volume 2, published in 1906: [Pg. 544] “He studied the view for a moment, then turned his horse, facing to the west, and said, waving his hand, “Move out that way.” “That is west,” I remarked. “Yes,” he returned. … [Pg. 544] “Pardon me, general,” I said, “but is there any special formation you would like me to take in attacking?” He replied, “No, I leave that to your discretion.” … [Pg. 549] “All the project required was to swing the Second and Third brigades to the left, pivoted on the First.” … [Pg. 566] “Much I doubt if anything of the kind could have been more laconic than the interview that then took place between us.”

[In fact, Wallace admits in his autobiography that he himself had drifted off course and the direction that Grant re-set for him in the afternoon led him to arrive in Shermans camps of the prior morning, not the “swamps.”]

From Wallace’s testimony to the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War 1863 Report Part 3 [Pg. 342] “I was left entirely to my own direction, except the simple direction which I had received at first. … About 4 o’clock in the afternoon General Grant came down to where I was—I had driven the enemy back then—and told me to change my direction again. As from the original position I was marching in a left oblique direction. The new change of position would take me back almost in the original direction I started from. I obeyed his order, of course, and marched on. About that time the enemy broke, and after that I understand it became a rout.”

From Lew Wallace’s Autobiography, Volume 2, published in 1906: [Pg. 566] Wallace had Grant saying, “You are getting along very well ; but you have swung round too far to the left, and are likely to get in the way of the general advance. To avoid that make a halfwheel to the right here, and then move on.” With that he turned and trotted hastily back the way he came.” … [Pg. 567] “The half-swing to the right was promptly made, giving me a bearing slightly north of west.” [Pg. 568] “We swept down a slope beyond the camp to a boggy brook. … In my haste to get rid of it, I plunged inadvertently into a swamp that tried all John’s great strength.”

Grant was worried that his freshest division “likely to get in the way of the general advance”? His second order basically took the 3rd Division out of the action by pointing it westward. It was the only division of his army that was in condition to conduct an extended pursuit that day, yet it was not directed south toward the enemy. It wasn’t even used the following day, as Grant gave Sherman and his beaten-up division the starring role in the pursuit. As stated before, Grant’s orders were both scanty and maladroit.

[Also, Rose claims that in the memoirs, Grant “went so far as to claim that the Army of the Ohio only arrived after the shooting stopped.” This is false.]

You’re wrong, Grant had written: “I do not remember that there was the whistle of a single musket-ball heard.”

[Rose criticizes Sherman for personal statements about Shiloh that conflicted with his account in his official report, but Rose includes a very negative Hurlbut letter to his wife about Shiloh without noting that Hurlbut’s official report sounded completely different.]

This is absurd criticism. Sherman told a plethora of lies about Shiloh after the battle and this should be taken into account. What Hurlbut told his wife immediately after the battle (“This battle was a blunder, one of the largest ever made. We were completely surprised, and for two days I got no order from Grant, but was left in this terrible fight to act on my own judgment. I could fight as far as I could see, but there was no general plan whatever.” … “Grant is an accident with few brains.”) is not something one would expect to find in an official report to his commander, and it corresponds with what is known.

Rose claims that Shiloh “represented a major strategic defeat” for the Union. This view fails to understand Hallecks stated strategy objectives.

I don’t care about Halleck’s stated strategy objectives; this was a strategic defeat, in that the move upon Corinth, instead of starting soon after Buell’s arrival, had to wait for the armies to refit. Worse, however, was that Pope’s advance down the Mississippi was reversed just as it was getting nearer to Memphis.

I’ll put my writing up against Dr. Smith, who made many mistakes in his book, writing that Grant’s morning messages from Savannah told Buell “to send his arriving troops on up the river as quickly as possible” and told Wood and Thomas “to hurry forward.” Smith has Grant supposedly telling Lew Wallace to ready the 3rd Division to march southward. He wrongly asserted that Sherman “openly argued that the war in the west would take hundreds of thousands of lives and years to complete ….” He incorrectly referred to Grant as commander of the Department of West Tennessee. He states that Grant went to Pittsburg Landing “every day.” Smith argued that “No one was looking for a Confederate attack.” Concerning the Battle of Belmont, Smith claimed that Grant “stabilized his own forces, and then eventually counterattacked to win the battle.” Smith had Grant arriving at Pittsburg Landing before 9 am, probably by 8:15-8:30. Worst of all is a pro-Grant perspective that minimizes the surprise of Grant’s unprepared troops and Grant’s responsibilites for both the surprise and the lack of preparedness.

Your heavy reliance on Wallace’s autobiography is concerning. If you think that Grant was a master of deceit, he could still have learned a few tricks from the author of Ben Hur. For one example only, did Wallace send. warning to Grant on “Thursday, April 4” that Johnston was headed to Pittsburg Landing?

How on earth is it a “strategic defeat” when the Confederates had to abandon Corinth after failing to prevent the juncture of the Union armies at PL? “Delay” does not equal “defeat”. (By the way, if I recall correctly Memphis fell within a few months)

These sorts of problems again raise a credentials question. Locating primary sources is always an essential starting point but then the challenge is analysis. You attack others for (allegedly) accepting Grant’s recollections as gospel. So you then rely on the recollections of another which in multiple instances are provably false.

By the way, speaking of Gail Stephens (see below(), she has Grant getting to PL by 8:30 and therefore at Crump’s by 8:00. And she uses a source other than Grant. As I know you know, time-keeping during the Civil War was not only not a science – it was barely an art.

Naval timekeeping was probably the gold standard when discussing the American Civil War. Using that, Tigress came up to Pittsburg Landing at 9:30. A.M.

Well, we have a conundrum. Wallace in his autobiography (Vol. 1 at 461) says the meeting with Grant at Crump’s took place at “about” 8:30. It looks like the time of certain events is all over the place – consistent with the relatively primitive time-keeping practices of the period. How far is Crump’s from Pittsburg Landing (and remember – the Tigress already had steam up)?. The inconsistencies cannot be conveniently attributed to Grant and his co-conspirators. Out of curiosity, by the way, what timepiece was the Tigress using?

It turns out that I was too kind to General Grant, regarding the time of his arrival at Pittsburg Landing. I and several historians had determined that around 9 a.m was a realistic estimate. But the logbook for the woodenclad gunboat USS Tyler, which Chief Ranger Stacey Allen commendably acquired, shows almost conclusively that Grant arrived even later than that. The beginning of the logbook’s relevant entry states …

Under the heading:

Pittsburgh

April 6th. 62

Came the entry for:

From 8 to 12

“Clear + Warm

heavy firing heard back of Pittsburgh. John Warner started down at 9. o’clk. Tigress Came up at 9.30 Evansville at 9.45 We got underway at 9.55 . . .”

With a typical estimate of an hour for Tigress’ trip upriver, Grant only left Savannah around an hour and a half after the first artillery fire at the army’s camp up the Tennessee. His arrival was an hour or more later than Tim Smith’s best guess.

And so now you have changed your own analysis. There’s nothing wrong with that but this discussion started with your attack on Tim Smith for accepting one of the multiple time frames we’ve been given by numerous participants. And before we decide that the Tigress was infallible (using a marine chronometer? something else?) and if we assume that Grant and Wallace briefly met at 8:15 (yours – “between” 8 and 8:30), it appears that it took the boat more than an hour to travel the short distance to PL when it had steam up and could move at 20 mph. Here’s another one. Brig. Gen. John McArthur and some others were under arrest on April 6. When Grant and his staff arrived at PL he ordered McArthur’s release. The commander of a regiment in his brigade (12th Illinois) confirmed that McArthur was back in command at the front at 9 AM. Do the math.

You can disagree about timing and you can even change your mind about timing. But you ought not go after somebody else for opting for another version presented by other witnesses just because it doesn’t fit your agenda.

Mr. Foskett: I do not know how to nicely reply when someone accuses me of a “heavy reliance on Wallace’s autobiography” when each of my two references to that work was preceded by my citing Wallace’s testimony to the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. In preparing my response, I also referred to Wallace’s after-battle report and comments he made in 1872.

All right – “reliance”. Is that better? And the point stands. Even Gail Stephens – hardly a member of the Grant “fan club” – pointed out that Wallace could be “fast and loose with the truth.” You seem to be rather selective as to whose accounts you choose to reject for lack of credibility. Wallace’s accounts on many events – especially Shiloh – frequently varied in material respects over the post-war years. And it became more exacerbated starting in 1886. Note the year. Good research will establish that conclusively if you care to do the work.

So, Wallace’s testimony to the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, which I have utilized unlike many other Grant biographers and even historians of the battle, should be considered a very good source of information. And it happens to generally corroborate Wallace’s autobiography in this matter.

If Wallace was a guy who (as Stephens concedes) played “fast and loose” with the truth, why is his testimony not subject to scrutiny just as his autobiography (justifiably) is?

All evidence should undergo scrutiny, of course. Unlike his or Grant’s autobiographies, Wallace’s testimony was only three months after the battle. It was probably done under oath or, at least, in a similar setting.

By the way, Wallace testified in Grant’s favor that, “As near as I can now recollect, about 8 o’clock, or 8.15 in the morning, General Grant passed up the river on a boat.”

Wallace was also good to Grant by testifying, “I only know from the remarks of others there is a great dispute as to whether General Grant was surprised or not. I do not undertake to say that the general was surprised. But from the statements of soldiers of some of the regiments, I am satisfied that some of his regiments were surprised. But on that point I will endeavor to do justice to General Grant, My opinion is that if there was a surprise, the responsibility does not properly attach to him.”

So, it seems quite believable when he made such statements as:

“The order directed me to move up with my division and take position on the extreme right of our lines, as they were on Sunday morning; and upon arriving at that point to form in line of battle at right angles with the river.”

“I asked for a diagram showing me the enemy’s lines and our own lines. It was promised me, but I never got it. I had to take a soldier and go myself in the night and ascertain as well as I could the position of the enemy relatively to my own position. … [Grant] gave me the simple direction to march forward with my command, in a direction that was directly at right angles with the river. That was about all the order I received.”

“I did not see General Grant until about 4 o’clock that afternoon. I was left entirely to my own direction, except the simple direction which I had received at first. … About 4 o’clock in the afternoon General Grant came down to where I was—I had driven the enemy back then—and told me to change my direction again. As from the original position I was marching in a left oblique direction. The new change of position would take me back almost in the original direction I started from.”

Here is the largest and freshest force under Grant’s control on the second day of battle and he hardly even watched Wallace’s division fight, much less give it any instructions.

Going back to the idea of scrutinizing sources, why is it that pro-Grant sources are so often accepted without scrutiny, even when the information is dubious, at best?

Rose: “[Pg. 568] “We swept down a slope beyond the camp to a boggy brook. … In my haste to get rid of it, I plunged inadvertently into a swamp that tried all John’s great strength.”

At this point in his narrative, the fighting is almost over, he considers himself advancing further than the rest of the army, he has already passed through the camps which he’s told are Shermans, and right after he crosses the brook he emerges into “parklike forest.” You take a little piece of a source, and spin it, and misrepresent what the source actually wrote.

Rose: “I do not remember that there was the whistle of a single musket-ball heard.”

Yes, and he ALSO wrote, “Before any of Buell’s troops had reached the west bank of the Tennessee, firing had almost entirely ceased.” The word “almost” implies there is still some shooting.

And he also wrote, “There was some artillery firing from an unseen enemy, some of his shells passing beyond us.” Artillery is shooting.

And he also wrote, “As his troops arrived in the dusk General Buell marched several of his regiments part way down the face of the hill where they fired briskly for some minutes.” Firing is shooting.

So not only is your statement wrong, but your phrase that Grant “went so far as to claim” is both judgmental and false.

Dan: Look at a map. Both times Grant gave orders to Wallace he sent him west or a little north of west. As we know exactly where Wallace started in the morning, we can be quite sure that Grant directed Wallace into the “almost impassable” bottomlands. Wallace had to make a half-wheel to the left.

Do you agree?

At 4:00 pm, when Wallace stated that Grant gave him the second order, the Confederate retreat was well underway, by most accounts. Grant sent Wallace westward through a swamp (if that’s how you wish it phrased), instead of having Wallace pursue.

Do you think that Grant’s orders, one or both, can be considered “maladroit”?

At one point, Wallace had move his force “by the flank” because his northern-most troops were crowded by the creek. But he then continued in the direction Grant had sent him. Wallace made other troop movements in order to align and face enemy troops. But he was still attempting to go in the direction that Grant sent him. And the course correction that Grant gave him at 4:00, was again to get him going in that direction.

No, Grant’s orders were not maladroit. He expected Wallace to handle his division like any other division officer.

Was Grant even There?

In the years following the Battle of Shiloh, the claims specifying the General’s time of arrival at Pittsburg Landing progressively moved that time backwards, with some claiming that General Grant arrived on the battlefield before 8 a.m. Why is this an issue? U. S. Grant was embarrassed at Fort Donelson by being miles away to the north when the Confederate breakout was attempted early in the morning of February 15th and did not meet with McClernand’s affected division until early afternoon… And Shiloh erupted in the pre-dawn of April 6th and General Grant was miles away to the north, out of contact with his Army at Pittsburg Landing. If it could be claimed that the General arrived on the Shiloh battlefield “shortly after the contest erupted,” then credit for the subsequent victory could be directly attributed to Grant; and his delinquency for being detached from his Army diminished.

But, there are problems regarding the Time. First, U.S. Grant had sent his keepsake timepiece home a day or two prior to Battle of Shiloh, and did not have a timepiece on his person during April 6th 1862. Second, there is evidence that “the eruption of artillery” involving Munch and Hickenlooper, in response to Swett’s Mississippi Battery just after 7 a.m. is the signal event that alerted General Grant and others at Savannah Tennessee; the booming artillery clearly heard, announcing that a major engagement was occurring somewhere towards the south. Third, Grant’s Flagship, the Tigress, could manage twelve knots. But it had to steam upstream against the 3-knot current of the Tennessee River; and the voyage of ten miles required about an hour. Fourth, the Tigress paused at Crump’s Landing. This delay could have been as little as five minutes; or as long as ten minutes. But there was time enough for Grant and Lew Wallace to engage in a brief discussion (and there was no decision reached by General Grant where was the point of attack: Crump’s or Pittsburg.) But Whitelaw Reid decided to clamber aboard the Tigress at Crump’s Landing and completed the voyage to the battlefield. Fifth, General Grant had injured his leg severely through a horse fall evening of April 4th and may have required assistance mounting his horse at Pittsburg Landing. Sixth, the United States Navy is the only organization that maintained precise time on the Tennessee River (accurate to the nearest minute.) And the USS Tyler recorded the time of arrival of the Tigress at Pittsburg Landing as 9:30 a.m.

What does it matter? I can believe Grant arrived at 8:30 a.m. And I can claim that General Grant arrived at Pittsburg even sooner, in time to make crucial early decisions. But it is difficult to dispute Facts, such as the accurate records maintained by the U.S. Navy.

[Access to Logbook of USS Tyler provided by a friend.]

“U. S. Grant was embarrassed at Fort Donelson by being miles away to the north when the Confederate breakout was attempted early in the morning of February 15th”

He was embarrassed? Source?

Autobiography of Lew Wallace vol.1 pp.399 – 400: “Nobody at headquarters felt authorized to act on my behalf.” [One of the tenets of command : “Someone is always in charge. Grant neglected this requirement during the operation against Fort Donelson when he departed the field to consult with Flag-Officer Foote, some miles away to the north.]

Mike Maxwell

Grant indicated that he arrived back on the battlefield somewhat after 10 AM, much earlier than he actually did. If he wasn’t embarrassed about the fact that he was away from his army at such a delicate point, there would be little reason to lie about the timing of his return.

“If it could be claimed that the General arrived on the Shiloh battlefield “shortly after the contest erupted,” then credit for the subsequent victory could be directly attributed to Grant; and his delinquency for being detached from his Army diminished.”

Delinquency? Either credit or blame, as may be applicable, belongs to the commander. Did either you or Rose serve in the military?

“Personal attack is the only refuge of too many angry but misguided critics” [Seattle Post-Intelligencer of 8 July 2004.]

Grant’s defenders often pick times far in advance of his actual arrival. Grant indicated that it was 8:30 AM early on, but then moved it back to about 8 AM in his Memoirs. Belknap, Putnam, Emerson, JH Wilson, Logan, and Rawlins all indicated it was around 8 AM. Rowley said it was about 7:30 and British historian Fuller even claimed that Grant arrived at the impossibly early hour of 6 AM.

They can lead other writers and historians astray.

So when do you say Grant arrived at PL? Is it now 9:30 based on the use of some unidentified time piece by the Tigress? Your own book pegs the meeting at Crump’s “between” 8 and 8:30. The meeting was extremely short, such that Wallace didn’t even board the Tigress. The 8:30 arrival time at Pittsburg Landing used by Stephens comes from the same Hillyer you cite regarding the Warner. And it was in an April 11, 1862 letter to his wife, not from some memoir put together after the Wallace delay controversy arose. You’ve proven one thing – there was a vast amount of uncertainty during the Civil War when it came to noting precise times. If there were 30 different time pieces in a unit you could easily get at least 5 different results.

If Grant was “embarrassed” by anything at Donelson, it was having two amateur division officers who weren’t sure what to do when the boss was gone.

It was the professional army officer, division commander Smith, who didn’t do anything significant in response to the Confederate attack at Fort Donelson until very late in the battle.

Perhaps because he had already sent McClernand a brigade the night before, and that brigade (McArthur’s) held off the confederates for three hours, which should have been enough time for McClernand and Wallace to get their act together.

The Donelson section of your book is as biased as the Shiloh section, selectively using bits of Wallace’s account but leaving out the parts that make McClernand look bad. Timothy Smith (again) is the gold standard among recent authors on Henry/Donelson.

Apparently it’s a “personal attack” to ask someone if they served in the military.