Questions of Secession (part one)

As a Richmond National Battlefield Park Volunteer, I have spent many Saturdays talking about the legality of secession with Nathan Hall, a historian and park ranger at Richmond. Nathan has been studying the topic deeply for many years. Over the next few days, I’m going to share some of my questions and, more importantly, some of Nathan’s answers.

Nathan earned his Bachelor’s at VCU and received a Master’s Degree from LSU, where he specialized in the legal and cultural history of the early republic. He studied secession in undergraduate school and did Masters-level research projects about Virginia’s path to ratifying secession. I recently asked Nathan to speak at the Richmond Round Table, and people really enjoyed his presentation. I think you’ll enjoy his thoughts, too.

Doug: In the context of American history, what is the difference between “secession” and “revolution”?

Nathan: First, it’s important to clarify that secession and revolution are not the same thing, though they can produce similar results—namely the change of one form of government to another.

Nathan: First, it’s important to clarify that secession and revolution are not the same thing, though they can produce similar results—namely the change of one form of government to another.

Simply defined, “secession” refers to a process of formally withdrawing from any organization. In the context of American history, secession is the assertion that individual states could, if they desired, opt to rescind their political ties to the federal government of the United States that were established upon the ratification of the U.S. Constitution in 1788.

Revolution, on the other hand, encompasses a much broader definition. The dictionary definition calls it any “a sudden, radical, or complete change” with the optional, more narrow definition of “a fundamental change in political organization.” In American history, revolution usually refers to the independence movement of the 1760s-1783. Notably, the separation of the colonies from the British government was not referred to as “secession” by its participants. The revolutionaries of 1776 were under no illusion that their independence would be accepted as legal, in the sense of its being sanctioned by British law. Instead, the Declaration of Independence claimed its authority as drawn from inherent, natural rights that all people possessed (“inalienable” in Thomas Jefferson’s parlance), meaning they did not need to look to the authority of the English king or of British law to justify their right to self-govern according to their preferred method. Thus, their action was not “secession,” because it was not understood to be a legally sanctioned withdrawal process, and was universally referred to by its participants as “revolution.” Herein lies the difference, for the purposes of American history, between secession and revolution. From the republic’s beginnings, revolution was stated to be a universal human right, and secession a formal procedure of law.

When tensions between federal and state governments escalated in 1833, James Madison offered a clear distinction of his view of how secession differed from revolution. He wrote to Daniel Webster, praising a speech that the latter had given in the Senate arguing against South Carolina’s assertion that they could nullify federal law or potentially withdraw from the union. Of the speech, Madison congratulated Webster that “It crushes ‘nullification’ and must hasten the abandonment of ‘Secession.’ But,” Madison cautioned Webster, “this dodges the blow by confounding the claim to secede at will, with the right of seceding from intolerable oppression. The former answers itself, being a violation, without cause, of a faith solemnly pledged. The latter is another name only for revolution, about which there is no theoretic controversy.”

To be continued….

The legality of Southern Secession was determined with completely settled finality when the North left Jefferson Davis untried, unconvicted, and unhung for treason.

Albert Taylor Bledsoe closed the case for us all.

But we should welcome attempts at re-opening it, because each new generation must face those hardest of truths that just won’t go away.

I think the North’s rationale for NOT trying him was precisely to leave the issue ambiguous rather than risk having it settled once and for all in a way that would turn out negatively for the North. Sure, the optics look bad on that, but it leaves the legal issues unsettled.

Nathan has some interesting background on that subject later in the series. I’ll be interested to hear your take on it!

Did the Northern veterans who lost limbs and suffered always in debilitating pain, and did the young widowed mothers in Illinois, vote upon that Ambiguity?

Are the National Cemeteries across the South that are filled with the Yankee dead who never made it back home up North, decorated with “Here Lie the Union’s Martyrs to an Ambiguity”?

Would they agree that their losses were worth the politicians’ ambiguous perspective on Davis’s treason against the unconditionally perpetual Union?

What is a Union that won’t hang its traitors?

There was no rationale to leave it ambiguous. There was no doubt in the minds of anyone in the US Government that unilateral secession was illegal. The Supreme Court ruled such and that settled the legal issues. The concern regarding Davis was he would have to be tried in Virginia, and there was a very big concern about jury nullification, where a jury of Virginians would refuse to convict him for treason no matter what the evidence.

Rev AE, there was more than just the legal reasons for not prosecuting and hanging these traitors. Many in the Johnson cabinet believed in a national reconciliation, one that was in the spirit of President Lincoln’s wishes and one that promised no more retribution. Additionally, it was believed that the 14th Amendment (Section 3) adopted in 1868 would be sufficient to ensure that former Confederate leaders would not hold State or Federal positions. Unfortunately, this provision ceased to be enforced after 1877.

“Unfortunately,” for whom?

It seems like you are insinuating the Federal government’s inability to enforce the 14th and 15th Amendements and the subsequent adoption of Jim Crow laws were somehow positive developments for the former Confederate States.

That’s where history becomes propaganda.

The Confederate Union was defeated by the United North, ostensibly so that all Southerners could become good citizens in the redeemed nation, made new.

But former Rebs weren’t allowed full citizenship rights. (They did have full citizenship rights in their own country before the Lee-Johnston surrenders.)

Suggesting that they as once-again American Citizens should not have taken their own side of the argument post bellum brings more into question than should be asked.

Or if asked, the morality of saving the Union just to punish those who had made their own, suited to the risks, needs putting on the Scale.

Agreed Rev. However, you, I and anyone else that doesn’t tow the victors history are derisively referred to as the lost causers. The legalities and constitution were just a hindrance to be ignored by Lincoln and the northern states and those that came after them, some disguised as historians.

The legality of secession is obviously still a subject of debate. Of less debate was its primary motive, spelled out plainly by its advocates in 1860-61 – the preservation of slavery. Was secession wise, prudent, or necessary? Hindsight would indicate no, to all three. Secession was instead the fevered, hasty overreaction to a presidential election. Secession’s disaffected opponents were in the minority in its early days – at least in the 11 states, they were majorities in MO, KY, MD, and DE. One segment, the mountaineers of western VA, seceded from secession. Others rebelled against secession – Appalachian & Ozark Unionists, thousands of former slaves, etc. By 1865, secession’s vocal proponents were decidedly less vocal. As years passed, more & different justifications for secession were manufactured, including the somewhat justifiable argument that it was legally right. As if a legal right absolves a person of a moral, natural wrong.

Tony, agreed. The Rev and Mr. Rainey conveniently leave out the great irony of the CSA. The Confederate government became an authoritarian regime led by an increasingly autocratic Jefferson Davis who frequently overruled his governors and enacted draconian laws. For all the criticisms of Lincoln’s overreach during the war, including habeas corpus, the draft, appointments, etc, the Confederacy generally introduced these same measures earlier in the war and to a greater extreme compared to the Lincoln administration.

Secession removed the risk of slaves into the U.S. territories, and ruined the Democratic Party’s chances in federal government.

Congress was finally liberated from the Slaveocracy.

The Secesh gave to Lincoln exactly what he had said he wanted.

Confederates tried to forcibly introduce slavery into US Territories – see Sibley, Baylor, and the short-lived Confederate Territory of Arizona. So much for “we just want to be left alone.”

Others who just wanted to be left alone were the people of East TN, western VA & NC, northern AL & AR, etc. Guess that whole “self determination” thing only went so far with Richmond authorities.

Doug Crenshaw: Great topic, and one that needs to be revisited. Because for too long we have been led to believe that secession was a spontaneous reaction to the election of Abraham Lincoln; and that the South was rightly concerned about abuse of Northern power as “potentially interfering with their established way of life.” The core to this discussion you mentioned in the first sentence: “the legality of secession.” Because what ignited the war was the Southern attack at Charleston Harbor… the second time (after the January 1861 attack on U.S. Flagged “Star of the West” was allowed to be explained away.) Disunion did not require war. Legal wrong required legal remedy. A truly offended section of the nation should have pursued legal redress through the Courts (the peculiar institution was protected in the U.S. Constitution.) And if permanent separation was determined to be the best remedy, that course should have been attempted through legal channels… first.

Mike Maxwell

The fact that the Johnson administration didn’t try Davis for treason was, to be sure, due to uncertainty about how a trial would come out. That, in turn, was because the question of secession’s legality was unclear in 1860. The Constitution is vague on the subject – no doubt deliberately so – and scholars had been arguing the issue for many years.

Pro-secesh folks cited the 10th amendment as proof of their view (and still do). Anti-secesh folks say that the spirit of the Constitution, with it’s desire for a “more perfect Union,” proves theirs. But the simple fact is that, in 1860, there was no settled law on the subject; no case law or court decisions. Opinions are fine but they’re just opinions.

In any case, the legality or illegality of secession didn’t require that Jefferson Davis be tried for anything. The question was settled in blood.

Nathan will get into a lot of this as the series continues.

While the Supreme Court had yet to rule specifically on secession in 1860, there was enough case law regarding the relation of states to the nation that it was obvious a unilateral secession [without consent of the other states] would be an unconstitutional act. Additionally, by March of 1861 three sitting presidents [Lincoln being the third] had made official declarations regarding secession, and all three said a unilateral secession [without consent of the other states] was an illegal act. Two sitting attorneys general had published their official statements saying a unilateral secession [without consent of the other states] was an illegal act. The story of Jefferson Davis’s is a complicated one, but the prosecution team had no doubt unilateral secession was illegal. Their concern was that since Davis would have to be tried in Virginia a jury of Virginians would not convict him no matter what the law or the evidence said.

No it was not that clear. Doesn’t matter what “sitting presidents” or attorneys general opined about. There was NO settled law. Secession was stupid but it was not, according to existing law, illegal.

A few other points, if I may. It is precisely because the legality of secession was unclear in 1860 that we should be very careful about calling southerners “traitors.” There was no consensus at the time as to whether a man’s primary loyalty belonged to the Union or to his state. There simply was none.

I once read a statement by a Pennsylvania officer (alas, it was many years ago and I don’t remember who he was or where I read it) to the effect that he was fighting for Pennsylvania. Had his state seceded, he would have worn gray and he still would have been fighting for Pennsylvania.

The point is that, if secession were legal (and, remember, there was no settled law saying it wasn’t), then southerners who went with their states could not have been traitors to the Union because they were not citizens of the Union, especially after acts of secession were passed. Calling southerners “traitors” in that case is like saying that Frenchmen who fought against Germany were traitors to Germany. It is absurd.

US Army officers who resigned their commissions to go South were no longer bound by their oaths once they were out of the army so they weren’t traitors eithers.

An argument might be made that someone like Longstreet, who accepted a Confederate commission BEFORE resigning his US commission could legitimately be called a traitor. One might also say that men from states which didn’t secede but who fought for the Confederacy also were traitors. Other than those arguable examples, however, the question of treason isn’t remotely clear.

Personally, I believe that secession was a boneheaded idea. And it was self-destructive. Had the Confederacy won, then any state at any time could have seceded for any reason. There would have been no stability at all.

And, let’s face it, South Carolina would fairly quickly have found some reason to grouse about the central government in Richmond. Texas, which actually had been an independent nation, might very well have realized how little it had in common with the eastern states of the Confederacy. The southern Mississippi River states had more common with the northern Mississippi River states and might well have seceded and formed a Mississippi River Republic with them. California and Oregon would have no reason to remain in the Union. New England might well have made common cause with Canada. All sort of issues would have arisen and secession would have then been the first, not the last, resort. Secession meant the balkanization of North America. That’s why it was such a boneheaded idea.

But boneheaded doesn’t mean illegal. As I said above, the legality of the issue was decided in blood.

Good points

Jim Morgan summarizes secession very well, describing it as “boneheaded.” There were many diverse factors that contributed to this issue, however. The United States was not truly melded as one nation until about the time of the Spanish-American War. Previous to that, and especially during the run-up to and the waging of the Civil War, individual loyalties were first-most to their respective state and secondarily to the nation. Further, the seceding states were largely led by wealthy planters and other citizens whose wealth would eventually be destroyed if the institution of human (black) bondage were totally abolished. In slave state Missouri a substantial majority of Missourians were moderates on the issues of slavery and secession. In the election of 1860, Lincoln received only ten percent of the Missouri vote, most of that in the Saint Louis area. Missouri voters had given over seventy percent of their votes to the moderate candidates, Northern Democrat Stephen Douglas of Illinois and Constitutional Union nominee John Bell of Tennessee. The state convention in early 1861, called by the legislature to consider the relations of the State of Missouri to the United States, did not include a single secessionist among the 99 elected delegates. Resolutions voted by the convention clearly reflected the political middle ground. Although a substantial majority of Missourians were moderates on the issues of slavery and secession, factions at each end of the political spectrum in Saint Louis began to organize and arm. Concern about the security of the federal Saint Louis Arsenal prompted the transfer of a company of U.S. Infantry, commanded by Captain Nathaniel Lyon, from Fort Riley, Kansas in early February to protect arsenal stores. A series of blunders by the impetuous hot-head Lyon, newly promoted to brigadier general of U.S. Volunteers, prompted a meeting between Lyon and Frank Blair with the Governor of Missouri Claiborne Jackson and former governor Sterling Price, commander of the Missouri State Guard militia, in Saint Louis on June 11. The meeting became contentious very quickly and Lyon egregiously declared war on the State of Missouri, a still-loyal state. He began to immediately conduct military action against the state. This polarized the State of Missouri; few remained in the political middle ground. The Missouri State Guard was now a force of the rebellion, not by choice but by survival reaction to aggressive, punitive action of the intemperate federal authorities. The Blair family was complicit in this tragedy. Missouri was subsequently voted into the Confederate States of America.

Sixth-Gen Missourian here, with ancestors in Blue and Gray. Ol’ Claib was complicit in this tragedy too. Pro-secession Missourians were a minority throughout the War. About 40k served the CSA, while about 120k wore the Blue suit. Kentucky saw a similar breakdown. Maryland also was Union-majority. And of course, western Va became West Virginia.

The Border States contributed about a quarter-million white men to the Union Army. The vast majority of them Southerners in culture & heritage. The 11 officially-seceded States contributed another 100k men to Union service – 30k of them from East TN. About another 150k Black Southerners served the Union Army. Combined, that’s a half-million Southerners in Blue. An impressive rebuke to secession.

With respect, Jim, that analysis is fundamentally flawed. The majority of the nation believed individuals owed allegiance to the nation first. The Constitution enshrined this with the Supremacy Clause and with the Treason Clause. There was no hesitation at the time in saying the rebels were traitors. As Ulysses S. Grant wrote to his father in April of 1861, “We are now in the midst of trying times when every one must be for or against his country, and show his colors too, by his every act. Having been educated for such an emergency, at the expense of the Government, I feel that it has upon me superior claims, such claims as no ordinary motives of self-interest can surmount. I do not wish to act hastily or unadvisedly in the matter, and as there are more than enough to respond to the first call of the President, I have not yet offered myself. I have promised, and am giving all the assistance I can in organizing the company whose services have been accepted from this place. I have promised further to go with them to the State capital, and if I can be of service to the Governor in organizing his state troops to do so. What I ask now is your approval of the course I am taking, or advice in the matter. A letter written this week will reach me in Springfield. I have not time to write to you but a hasty line, for, though Sunday as it is, we are all busy here. In a few minutes I shall be engaged in directing tailors in the style and trim of uniform for our men.

Whatever may have been my political opinions before, I have but one sentiment now. That is, we have a Government, and laws and a flag, and they must all be sustained. There are but two parties now, traitors and patriots and I want hereafter to be ranked with the latter, and I trust, the stronger party. I do not know but you may be placed in an awkward position, and a dangerous one pecuniarily, but costs cannot now be counted. My advice would be to leave where you are if you are not safe with the views you entertain. I would never stultify my opinion for the sake of a little security.”

Secession didn’t come before the courts until the Civil War, so they couldn’t rule until the war. Once that happened, though, courts ruled several times on secession and on the status of the rebels. In each and every case, with no exceptions, the courts ruled unilateral secession was illegal and didn’t hesitate to call the rebels traitors, from the Prize Cases onward. In Shortridge v. Macon, for example, Chief Justice Chase ruled that a state’s action in declaring it had seceded did not excuse an individual from being a traitor. Congressional acts during the war specified the rebels were traitors. For example, the Confiscation Acts were officially titled acts to “Punish Treason.” After the war, Andrew Johnson pardoned all the rebels for the crime of treason. Had they not committed treason there would be no need to pardon them for treason. During the war there had been rebels who were convicted of treason.

I can understand the reconciliationist urge that motivates one to defend brave men from the charge of treason, but we do no one any favors by whitewashing their actions. No one today is arguing we should dig up their bodies to hang them for treason. There is a consensus that not prosecuting them was the right decision as it facilitated the reunion of the sections. The argument today concerns monuments and whether the United States should be honoring men who committed treason against the United States.

The oaths officers took at the time was that they would support the United States “against all opposers whatsoever.” That was the oath R. E. Lee, for example, took in late March of 1861 when he accepted promotion to colonel from Abraham Lincoln. But when the United States was faced with an opposer who had fired on the flag, instead of supporting the United States against that opposer, Lee resigned. It’s true the act of resignation released him from his obligations to the US Army, but in my opinion anyway, the act of resigning while the United States faced an enemy in the field was in and of itself a violation of his oath. In any event, violating the oath was not treason. Levying war against the United States was treason. It was every bit as much treason as it would have been had Lee resigned his commission in 1846 and then went on to fight for the Mexicans in the Mexican-American War. The oath isn’t the important thing–levying war against the United States was the important factor, and no one can deny the rebels levied war against the United States.

Al Mackey makes great points. US Army and Navy officers who swore an oath to the United States and then proceeded to join a secessionist rebel government and lead military forces against the armies of the United States is the very definition of a traitorous act. If you recall, the US government’s official designation for the conflict was the War of the Rebellion. Lets not split hairs between the terms rebels and traitors.

If Dwight Eisenhower resigned his commission in 1941 and joined Germany against the Allies, I think all would characterize this as a traitorous act. If David Petraeus resigned his commission and joined a secessionist movement in Idaho in an armed conflict against the US, I think all would characterize this as a traitorous act.

Yes, feelings of allegiance to one’s state were very strong and a deciding factor at the time. However, many Southern-born officers acknowledged their oath and loyalty to the United States (and to the Union) when they made their decision. Men such as Winfield Scott, George H. Thomas, and Montgomery Meigs, to name a few. Meigs is a good example of a staunch southern Unionist who happened to be close friends with RE Lee before the war. Meigs thought Lee should suffer for Lee’s decision to fight against the United States, hence the creation of Arlington National Cemetery.

.

Regarding the Arlington National Cemetery, after the war, the Federal government was forced to pay the Lees compensation for the illegal taking of same.

In 1861 there were six Virginians serving in the U.S. Army as full colonels on active duty. Lee was the only one who did not keep faith with the oath taken on promotion to colonel. Weren’t those other five colonels Virginians as well?

Samuel Phillips Lee, R. E. Lee’s cousin and fellow Virginian, said, “When I find the word Virginia in my commission I will join the Confederacy.” His brother, John Fitzgerald Lee, was a Union Army Judge Advocate.

Another cousin, Laurence Williams, served as an aide-de-camp to George McClellan.

Anne Lee Marshall, R. E. Lee’s sister, was a Lee, a Carter by her mother, and a Virginian. She was a Unionist during the Civil War, and her son Louis Marshall served in John Pope’s Army of Virginia against R. E. Lee.

John Pemberton, a Pennsylvanian, served in the confederacy. Maryland never seceded, nor did Kentucky, yet many men from both states served in the confederacy. State loyalty is overstated these days in an effort to excuse the actions of the confederates. State loyalty doesn’t explain the guerrilla warfare in Missouri.

Now that you mentioned Maryland, she never had the chance to leave because she was invaded, her legislature placed under arrest, thousands of Marylander’s were placed in prison, (including the grandson of Francis Scott Key), the free press shut down, property illegally confiscated and Union soldiers allowed to vote in Maryland’s elections. A notable book on Maryland during the secession crises is titled, “A Southern Star for Maryland: Maryland and the Secession Crises, 1860-1861 written by Lawrence Denton, a Johns Hopkins faculty member. There is no doubt that had MD not been invaded, she would have joined her sister states.

The nation, i.e. the People in the aggregate, per Story and Lincoln’s imaginative myth, did not write their Patriotic Dreams into the Federal Constitution.

All interpretations made, all answers attempted, must defer to the founding Ratifiers, who were representing ONLY the citizens of the separate States.

The States take priority for all orders of political-governmental-national allegiance, most especially for us when critically examining the most searing context of the One Nation at War against the South.

(Emerging Civil War should create some real excitement by openly encouraging and financially supporting young scholars in researching the Sumberged Civil War…)

Family first, then Kinsmen-Neighborhood-Zip Code-Town or City-County-Metropolis-STATE-Region-Section-COUNTRY-Continent-Hemisphere-Planet-Solar System.

(Wiser ones can insert Race and Religion, Language and Humanity, based upon their scientific methods and provable results.)

Attempts at enforcing any reordering of that Loyalty Continuum upon the attitudes and within the world-views of the State Citizens always require a reinforcing rhetoric of “values,” followed by brutality, and thus its virtuous abstractions are negated by its vile immorality

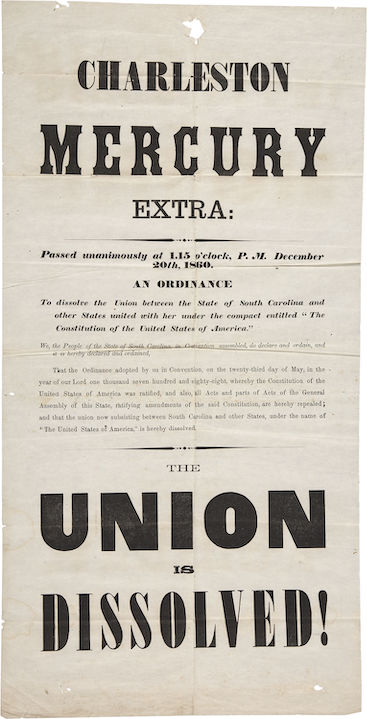

The posted Charleston Mercury broadside pronounces and fosters a dangerous falsehood, which is still believed today by some.

Who can spot it?

I guess it was only a matter of time before the ahistorical “tyrant Lincoln” myth reared its head.

McClellan arrested some members of the Maryland Legislature based on information he was given that they were part of a confederate plot, acting in conjunction with a raid by confederate military forces. Recall that Jackson was at Harpers Ferry, about 20 miles away from Frederick, where the legislature was meeting.

The Maryland Legislature, meeting in Frederick on 26 April 1861, voted that there was no constitutional authority for secession. General McClellan did not issue the order to arrest secessionist legislators until 12 Sep 1861 [OR Series II, Vol I, p. 563]

Nathaniel Banks did receive instructions, based on the information he obtained, from Simon Cameron to prevent a secession vote.

WAR DEPARTMENT, Washington, September 11, 1861.

Maj. Gen. N. P. BANKS,

Commanding, near Darnestown, Md.

GENERAL: The passage of any act of secession by the Legislature of Maryland must be prevented. If necessary all or any part of the members must be arrested. Exercise your own judgment as to the time and manner, but do the work effectively.

Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

SIMON CAMERON,

Secretary of War. [OR Series II, Vol 1, p. 67]

Governor Hicks of Maryland approved the action.

STATE OF MARYLAND, EXECUTIVE CHAMBER,

Annapolis, September 20, 1861.

DEAR SIR: We have some of the product of your order here in the persons of some eight or ten members of the State Legislature, soon, I learn, to depart for healthy quarters. We see the good fruit already produced by the arrests. We can no longer mince matters with these desperate people. I concur in all you have done.

With great respect, your obedient servant,

THO. H. HICKS.

Maj. Gen. N. P. BANKS.

[Ibid., Series I, Vol V p. 197]

EXECUTIVE CHAMBER, Annapolis, November 12, 1861.

Hon. W. H. SEWARD, Secretary of State.

DEAR SIR: Having heard last evening whilst in Baltimore that you had an idea of releasing from their confinement at Fort Warren, &c., such members of our former distinguished Legislature as have been superseded by the election of successors I trust, sir, you will excuse me for obtruding a word of admonition upon the subject. I beg that you be particular.

To liberate such men as Landing, of Worcester; Maxwell, of Cecil; Claggett, of Frederick, &c., will do us little injury in Maryland; but to release Teackle Wallis, T. Parkin Scott, H. M. Warfield, &c., will be to give us as much trouble here as would the liberation of Mayor Brown, George P. Kane, the police commissioners of Baltimore, and other like spirits to them. We are going on right in Maryland and I beg that nothing be done to prevent what I have long desired and labored for, viz, the identification of Maryland with the Government proper. Everything is working well here and although I have felt that I have not been treated in some instances as I had a right to expect I intend to do my duty and aid to save the Union. I close by saying be careful–do not be over liberal with these fellows.

Your obedient servant, &c.,

THOS. H. HICKS.

[Ibid., Series II, Vol I, pp. 704-705]

According to McClellan, “The total number of arrests made was about sixteen, and the result was thorough upsetting of whatever plans the secessionists of Maryland may have entertained. It is needless to say that the arrested parties were ultimately released, and were kindly treated while imprisoned. Their arrest was a military necessity, and they had no cause of complaint. In fact, they might with justice have received much more severe treatment than they did.” [George B. McClellan, McClellan’s Own Story: The War for the Union, pp. 146-7, quoted in Mark E. Neely, Jr., The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties, p. 16]

Regarding newspapers, James G. Randall tells us, “In seeking a just interpretation of the question of press control during the Civil War, one must balance the immediate and practical considerations, of which the executive branch must be ever watchful, with the constitutional and legal phases of the subject. When powerful papers were upsetting strategy by the revelation of military secrets, discrediting the Government, defaming the generals, weakening the morale of soldier and citizen, uttering disloyal sentiments, fomenting jealous antagonism among officers, and clamoring for a peace which would have meant the consummation of disunion, even the most patient administration charged with the preservation of the Union by war, would have been tempted to the use of vigorous measures of suppression.” [James G. Randall, Constitutional Problems Under Lincoln, p. 505]

Randall says, “A striking fact concerning the subject of journalistic activity during the Civil War was the lack of any real censorship.” [p. 481]

Lincoln’s policy on suppression was very clear. Here’s Lincoln’s stated policy:

“Under your recent order, which I have approved, you will only arrest individuals, and suppress assemblies, or newspapers, when they may be working palpable injury to the Military in your charge; and, in no other case will you interfere with the expression of opinion in any form, or allow it to be interfered with violently by others. In this, you have a discretion to exercise with great caution, calmness, and forbearance.” [Lincoln to John M. Schofield, 1 Oct 1863, _Collected Works,_ Vol 6, p. 492]

In the matter of arbitrary arrests, as amazing as it sounds, nobody had ever done a systematic study of this issue until Mark Neely undertook it in his 1991 book, The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties.

“In 1861, 166 of the 509 cases of known residence involved Marylanders, that is, 32.6 percent.” [Mark E. Neely, Jr., The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Rights, p. 75] Not “thousands.”

According to Neely, few of the arrests “involved questions of freedom of speech, press, or assembly. Most prisoners were rather ordinary characters arrested on suspicion of contraband-trading, desertion, or draft-dodging.” [p. 131] Add to that those arrested for spying, those arrested because they were confederate citizens, and those arrested for selling liquor to soldiers and other crimes, and the number of individuals arrested for political reasons shrinks even more.

As we can see here, the number of people arrested for political reasons was very small: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/j/jala/2629860.0005.103/–lincoln-administration-and-arbitrary-arrests?rgn=main;view=fulltext

And please don’t inflate Mr. Denton’s reputation. He wasn’t a faculty member, he was part of the administration, specifically Dean of Admissions. He’s wrong about Maryland.

Dentons stats are well documented, and Gov Hicks was somewhat of a coward once the state was invaded. He was only looking out for his own hide. Lincoln received what percentage of votes in the 1860 election from MD?

I’m sorry Al but I think you’re missing the point. Any court cases that happened after the war are irrelevant. Ex post facto law doesn’t count and is unconstitutional. And it doesn’t matter what Grant thought. I repeat: there was NO SETTLED LAW at the time the southern states seceded. That’s all that matters.

You said: “It’s true the act of resignation released him (Lee) from his obligations to the US Army, but in my opinion anyway, the act of resigning while the United States faced an enemy in the field was in and of itself a violation of his oath.”

Your opinion. Not law. If it released him from his oath, then it could not have been a violation of that oath and, therefore, could not have been treason.

The State of Maryland was likely split in two: Union-supporting citizens vs. those favoring Secession. Either path adopted, someone was going to be unhappy. And the outcome had potential to mirror what took place in Missouri. And there is more… No effort was made to “interfere with Maryland” until Fort Sumter was fired upon. As consequence of that aggression, State soldiers from Massachusetts were attacked in late April by a mob in Baltimore while on their way to defend the United States Capital. Once rebellion was initiated, subsequent actions had little to do with “giving them an opportunity to secede” and everything to do with “defending the United States” …which evolved into “winning the war.”

Just 85 years before, the 1776 DOI states “That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, –That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.” So “…the minutiae of the legality of succession” is actually a very important topic involved in the rise & fall of nations throughout civilized history (including ours). So – is the consensus that the “American Revolution” was ‘patriotic’ – but Southern secession was “boneheaded”? I’ll bet King George III would have disagreed! Just as an analogy, why is a divorce legal – and secession is not? The US Constitution was an agreement / legal contract (not an edict) between the 13 original states. And the legal understanding of an agreement / contract is that it can be amended or rescinded by the parties. Whether I’m filing for a divorce or returning a waffle iron to Best Buy, the right to rescind an agreement between parties is valid – just ask any divorce attorney. The problem comes in that if the South did have a legal right to rescind the original agreement and form a new government – then the North did not have the right to coerce (esp. militarily) the South to do otherwise. Gov. Ellis of NC responded appropriately when he received Lincoln’s demand for troops on April 15 – ” Your dispatch is recd. and if genuine which its extraordinary character leads me to doubt I have to say in reply that I regard the levy of troops made by the Administration for the purpose of subjugating the States of the South, as in violation of the Constitution and a gross usurpation of power. I can be no party to this wicked violation of the laws of the country, and to this war upon the liberties of a free people. You can get no troops from North Carolina.”

President Buchanan, prior to leaving office, stated, “the federal government does not have the constitutional authority to wage war on any state”. The majority of Americans, prior to hostilities, were for a peaceful separation. President Lincoln strung the peace commission along until he had all of his sinister pieces in order to goad the south into firing the first shot. There is not doubt that President Lincoln trashed the Constitution and Bill of Rights of not only southerners, but thousands in the north as well that opposed the war and/or spoke out against Lincoln.

Lost Causers love the debate the minutia of the legality of succession. It’s a sophists’ debate. Legality be damned.

Thank God the North won. Slavery was abolished and our dear United States of America remains the United States of America.

Mr. Ruth, the law matters. It’s not a question of being a Lost Causer. I’m glad the Union was preserved. I’m simply saying that the question of treason in 1860 was not as clear as it is now. Where a man’s primary loyalty belonged was an open question.

Mr. Berkoff says above, “If Dwight Eisenhower resigned his commission in 1941 and joined Germany against the Allies, I think all would characterize this as a traitorous act.”

That’s no doubt true but doesn’t matter in the context of 1861. The World War II context, and the general American view of loyalty was completely different.

I really don’t know how to make it any more clear that there was no settled law about the legality of secession in 1860. None. What else could possibly matter? The stupidity of secession is a question entirely different from it’s legality.

Washington and Lee (as of his January 1861 letter to his son) had their firm views on the issue. The secession acolytes conveniently ignore those.

Jim, as I mentioned earlier, men like Meigs and Thomas wrote extensively about loyalty to the Union and the United States despite their Southern birth.

Your argument that these men who lived 160 years ago had little appreciation for a “loyalty” to the Union or that the concept of a Federal government had not yet matured is false and disingenuous. Moreover, you will find the term “traitor” and “traitorous” used in letters and speeches by many Unionists during the war. This is not a modern development.

At the end of the day, there’s a limit on how far “legal process” can deal with these types of issues. If secession was legal, then would seem to follow that the recourse would be via the courts, not arms. Once you take up arms it pretty much ends any sort of legal aspect.

During the nullification crisis, Jackson sent VP Van Buren to NY state to draft an administration response. Van Buren used his influence/political power to push his writing through the legislature as a state resolution. Van Buren took the opportunity to opine beyond the question of nullification to the broader questions which nullification implied. His basic conclusion is you can’t secede without approval of the other states. It appears the states tried to finesse the issue by acting through “popular” conventions rather than the established state legal machinery. But it seems to me these conventions are extra-constitutional so their appeal is to the Jeffersonian higher authority.

The posted Charleston Mercury broadside pronounces and fosters a dangerous falsehood, which is still believed today by some.

Who can spot it?

I look forward to this series and all the hoopla that will follow in the comments.

LSU grad here too.

I am of a similar mind as Jim Morgan’s comments. It was a Civil War… who is a traitor in a Civil War?

It was the War of the Rebellion. Who were the Rebels?

Todd,

I am not convinced it’s true that rebellion is ipso facto treason. More power to you for thinking that, but it’s not what I think.

I think the Civil War was a civil war, and that both sides fought for what they believed in and went about it in as lawful a manner they thought was necessary. I think some of our Union forefathers recognized this a well and it’s the reason, in the end, they didn’t treat former Confederates as actual traitors.

In my mind it was the war for Southern Independence, they had no desire to conquer the US federal government. The common CSA soldier, when asked why they were fighting, answered for their independence and because you are here.

The question of Secession’s legality was engaged at the outset, with “opt to rescind.”

Opt means that rescinding was an option available to all states who had voluntarily opted for ratifying the Constitution, and who had thereby joined in union with others of these United States.

The question of legality was answered in the framing of the question.

The follow up question should have been about the legality of the War Against Rescinding.