William McLain: On the Subject of Surrendering

ECW welcomes guest author Dan Masters.

By August 1864, William Mosby McLain of Co. B, 32nd Ohio Infantry had become an expert on the ins and outs of surrendering. Having taken part in two of the largest mass surrenders of the Civil War and narrowly escaping individual capture in battle, he experienced the “art” of surrendering from both sides of the equation.

His first brush came in September 1862 when his regiment, as part of the Harper’s Ferry garrison, was surrendered by Colonel Dixon Miles. It was a bitter experience for McLain, made doubly so by the significance of the date for the 32nd Ohio. “We surrendered on Monday September 15, 1862,” he wrote. “It was a day pregnant with memories to our regiment. Just one year previous we had left Ohio and gone into Virginia. Just one year of campaign, one year of toil and peril, of marches and camps, in the bitter cold or the enervating heat, one year of absence from home, from everything civilizing, everything refined, one year spent in unused hardships and all for what? To be at last sold, betrayed, disgraced, captured?”[1]

McLain, his father an anti-slavery minister from Ohio and his mother a Virginia relative of noted Confederate cavalryman John Singleton Mosby, was living in Richmond, Virginia finishing up his college studies in civil engineering when Virginia seceded in April 1861. His sympathies lay with the North, and he returned to his father’s native state where he soon enlisted in the 32nd Ohio. To be surrendered at Harper’s Ferry to former neighbors and kin was a mortifying experience. The experience was made worse by the ragged appearance of his captors. “An army will look ragged and weather-beaten after such marches as they have lately had, but I never dreamed that God’s images could become so defaced: ragged, dirty, lousy, lean, haggard, hatless, shoeless, blanket-less, often bootless and shirtless for many of them had a strip torn from some old tent to serve in place of coat and shirt in the day and blanket at night. I don’t believe there were a hundred good pairs of socks in the whole corps nor many more of shoes or boots. Their uniform- p’shaw, they had none! Their clothes were of all sorts, sizes, shapes, kinds, colors, and cuts. From the old short-waisted long-tailed blue dress coat of the Revolution to the still more short-waisted jacket; so short, indeed, that it generally exposed a zone of dirty shirt between wind and water giving one the idea that pants and coat where bound in different directions,” he commented acidly.[2]

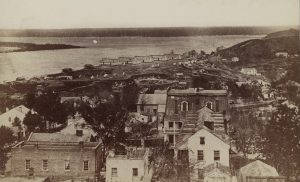

McLain’s second encounter with the art of surrendering came under happier circumstances than the first. In January 1863, the 32nd Ohio was paroled and sent to join General Ulysses S. Grant’s Army of the Tennessee in its drive to capture Vicksburg, Mississippi. The regiment was hardly welcomed upon their arrival: Grant’s veterans dubbed the Ohioans the “Harper’s Ferry cowards” and generally made life miserable for them. That is until the regiment proved its mettle by charging on and capturing a Confederate battery at the Battle of Champion’s Hill. McLain and his regiment took part of the siege of Vicksburg and witnessed first-hand the surrender of the Confederate garrison. “Vicksburg fell into our hands and to make it complete all of this is done in celebration of the 4th of July,” he wrote joyously the day of the surrender. “I’ll guarantee that not one heart among you throbbed more joyously than mine when I saw the little white flags stuck on all the forts and the graybacks crawling out to stack arms. I had seen such a sight once before, but then they surrounded me, and their significance included me. Now I surrounded them, and their significance pointed me to a rift in the war clouds. I seemed to see in them the beginning of the end, and I felt proud. This is the biggest 4th of July that I have ever spent.”[3]

A year later, the 32nd Ohio had joined William Tecumseh Sherman’s army in Georgia on its drive to capture Atlanta. McLain, his health ruined by three years’ hard service in the field, had been placed on special duty with the regiment. Utilizing his education in civil engineering, Colonel Benjamin Potts appointed him engineer in charge of directing the construction of fortifications. McLain’s new position was no sinecure; he was at the front constantly with his comrades and shared in their dangers. At the Battle of Atlanta fought July 22, 1864, the 32nd Ohio was nearly surrounded and he narrowly escaped capture. McLain was left behind when the regiment retreated and he had to employ some clever strategy to avoid capture. He gave some more insight into the circumstances of this battle in the following letter penned August 8, 1864:

“For nearly an hour we fought without change of position until the word was brought that the Iowa brigade (inside the works) had fallen back from our alignment and the Rebels were now completely between us and the rest of our forces. I looked at [Lt.] St. Duncan, assistant adjutant general of the brigade, and saw that he thought it a bad position of affairs, but he didn’t despair, so I concluded I wouldn’t. He ordered us to fall back to the woods in our rear a company at a time, and they began with Company A on the right. We kept up a steady fire from our flank to protect the maneuver and soon our turn came. I was starting when one of my comrades on my right was shot through the chest, turned his face, and said, Oh, Will!” I thought he wanted water, but I knew we couldn’t carry him off and stopped to give him my canteen, but he didn’t want water and caught me by the hand. He tried to say something but could not and while he held me his gasped his last.

“I rose up from my knees and looked around. The company was out of sight in the timber but the Rebs were in sight and plenty of them. I saw it was too late to run and as there was nothing larger than a cornstalk to hide behind, I had to come up with a strategy. I lay down on my face and lay stark and stiff as if I were as dead as poor Mitchell beside whom I lay. On came the rush. I expected every moment to feel a bayonet thrust through my ribs or a musket butt on my head. But they passed and I was safe! Still the balls were falling around me from our own men and the battle raged fiercely on top of the hill about 100 yards off, but it was in the woods and there was only one line of Rebels and I felt confident that our regiment was good for them, so I began looking for a hiding place to bide my time. I had no desire to be captured having tried that twice during my three years. But here came the Rebels flying back, their line broken and mangled; while our boys raised such a shout as I never heard a regiment give before. Oh, I wanted to add to it to the top of my lungs, but I didn’t dare as I had to play dead man again. I tell you it was a terrible moment. I wouldn’t take a thousand dollars to pass another such moment. Still the good God was overseeing all and he preserved me. Never did I utter a more fervent prayer of thanks than I did that night.

“They passed, and I took a gun and drew my revolver to be ready for any straggling or wounded Johnny that might be between me and the regiment for I was determined to get to it or die, so off I started. But there were only dead and badly wounded along my route and they let me alone, so I didn’t bother them, and I regained the regiment. We numbered 102 less men than we had an hour previous and Company B was short by 11 files, 22 good men and true.” [4]

The Atlanta campaign was McLain’s last as he was mustered out of service August 19, 1864 at Chattanooga, Tennessee. He returned to Ohio until the close of the war then ventured west to help build railroads. McLain’s last job was with Texas & Pacific Railroad and there he died of heart disease September 8, 1873 in Gladewater, Texas at the age of 35. His remains were shipped back to Washington, D.C. and he is buried with his parents at Oak Hill Cemetery. [5]

[1] Masters, Daniel A., editor. The Seneachie Letters: A Virginia Yankee with the 32nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry. Perrysburg: Columbian Arsenal Press, 2020, pg. 105

[2] Masters, op. cit., pgs. 105-106

[3] Masters, op. cit., pg. 160

[4] Masters, op. cit., pgs. 221-222

[5] Masters, op. cit., pg. 229

Dan Masters holds a bachelor’s degree from the University of Toledo and has been actively engaged in Civil War research for more than twenty years. Dan lives in Perrysburg, Ohio with his wife and five children, while his oldest son is currently serving in the U.S. Air Force. His work has been featured in America’s Civil War, Maryland Historical Magazine, The Western Tennessee Historical Society Papers, and Northwest Ohio History. Dan is the author of six books about the Civil War, the latest being The Seneachie Letters: A Virginia Yankee in the 32nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry published by Columbian Arsenal Press. He also frequently posts articles to his blog: https://dan-masters-civil-war.blogspot.com/

I have McLain ancestors in the Civil War from NW Ohio, but they served in MI regiments.

i wonder if they were not only paroled, but also exchanged, in order to join grant’s forces ?