Hellmira’s most distinguished inmate—Anthony M. Keiley

If there is one thing I have learned from studying the Civil War for much of my adult life, it is that it is a period filled with colorful and eccentric figures. Researching my recently released book, Hellmira: The Union’s Most Infamous Civil War Prison Camp – Elmira, NY, I met just such a character: Anthony M. Keiley.

If there is one thing I have learned from studying the Civil War for much of my adult life, it is that it is a period filled with colorful and eccentric figures. Researching my recently released book, Hellmira: The Union’s Most Infamous Civil War Prison Camp – Elmira, NY, I met just such a character: Anthony M. Keiley.

A Confederate prisoner of war who found himself incarcerated in the Elmira POW camp in 1864, Anthony Keiley was far from your typical Rebel inmate. College-educated, urbane, well-spoken and a gifted writer, the Virginia prisoner was also a member of the Virginia House of Delegates. In contrast, the typical Confederate prisoner housed along the Chemung River was a farmer or mechanic possessing a grade-school education. Mostly foot-soldiers from Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, few prisoners in Elmira could make a claim to gentleman status as Keiley did.

A Yankee by birth, Keiley was born Sept. 12, 1833 in Paterson, New Jersey, to John and Margaret Keiley. Both parents were of Irish decent; Margaret was born there. John was a teacher by trade who worked variously as a tutor and at a seminary. After completing studies with tutors, Anthony attended the Randolph-Macon College in Ashland, Virginia.

Prior to the Civil War, Keiley worked as co-publisher of a small newspaper in Petersburg, The Southside Democrat, and later read the law and was admitted to the bar in 1859. The budding journalist and lawyer viewed the approach of war with much anxiety. With the cascade of Southern states seceding following the election of Lincoln, Keiley was “staunchly opposed to secession of Virginia from the Union.”[i]

Despite his misgivings over secession, once Virginia joined the Confederate cause, Keiley jumped to Virginia’s defense. Enlisting in Co. E, 12th Virginia Infantry, in April 1861, the idealistic young attorney would soon be a first sergeant and later ascend to lieutenant, leading his companions into the fraternal bloodbath of war.

During the Battle of Malvern Hill, part of the Seven Days Battles of 1862, Keiley was severely wounded and, in fact, reported as deceased. Later, after recovering from his wounds, Keiley joined Lee during the Gettysburg Campaign before resigning to join the Virginia House of Delegates.

Keiley was not an active soldier when he was captured by Union forces near Petersburg in June 1864. Called to defend the city when every able-bodied man hastened to repel a thrust by Union Gen. Benjamin Butler, Keiley was literally in the wrong place at the wrong time and was nabbed by Federal forces. Sent to the Union’s largest POW camp at Point Lookout, Maryland, the Virginia politician became a keen observer of prison life and an aspiring philosopher. Though his diary and later book about his days incarcerated, Keiley would make important contributions to the literature of the Civil War.[i]

Observing how incarceration influenced the character of men, Keiley observed,

men become reckless, because hopeless – brutalized, because broken-spirited, until from disregard of the formalities of life, they become indifferent to its duties, and pass with rapid though almost insensible steps from indecorum to vice – until a man will pick your pocket in a prison, who would sooner cut his own throat at home.[ii]

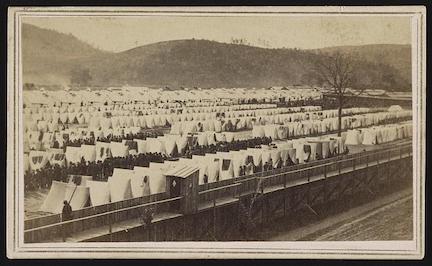

In July 1864, Keiley was transferred to a new Union prison camp along the banks of the Chemung River in New York’s Southern Tier. Erected shortly before his arrival, the Elmira POW camp was built to help alleviate the overcrowding at Point Lookout. A major railroad hub, connecting central and western New York to places South, and containing a former draft rendezvous with infrastructure already in place, Elmira made perfect sense to the Union high command as a place for a POW camp.

In July 1864, Keiley was transferred to a new Union prison camp along the banks of the Chemung River in New York’s Southern Tier. Erected shortly before his arrival, the Elmira POW camp was built to help alleviate the overcrowding at Point Lookout. A major railroad hub, connecting central and western New York to places South, and containing a former draft rendezvous with infrastructure already in place, Elmira made perfect sense to the Union high command as a place for a POW camp.

Early in his tenure in Elmira, Keiley was enchanted by the hills and the temperate climate. He was especially impressed with the water, “which was here pure, cool, and abundant; and the new comers luxuriated in the delicious beverage with the gusto of a lost traveler in Sahara, or a repentant legislator after a nocturnal spree.”[iii]

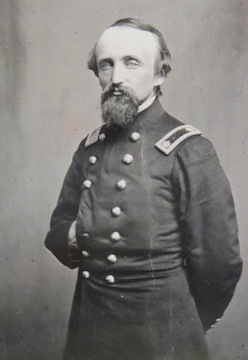

Just as Keiley was not your typical inmate of Elmira, his experience living in the camp was similarly atypical. Possessing both education and ability, the Virginian was soon given a job at the facility and special quarters. He also cultivated the friendship of the commandant Major Henry V. Colt. In his memoirs, Keiley praised Colt as “uniformly urbane and courteous in his demeanor.” And while Keiley could be savage in his condemnation of the Elmira camp in his memoir, he had nothing but admiration for Colt, who he said “discharges the…offices of his post with a degree of justice to his position and to the men under his charge, a patience, fidelity, and humanity that could not be surpassed…”[iv]

On August 21, 1864, Keiley learned there had been twenty-nine deaths the previous day and raged in his journal: “Air pure, location healthy, no epidemic,” he wrote in his diary, concluding darkly, “The men are being deliberately murdered by the surgeon.” Keiley added, “Especially by either the ignorance of the malice of the chief,” referring to Dr. Eugene Sanger, Elmira’s chief surgeon.[v]

On August 21, 1864, Keiley learned there had been twenty-nine deaths the previous day and raged in his journal: “Air pure, location healthy, no epidemic,” he wrote in his diary, concluding darkly, “The men are being deliberately murdered by the surgeon.” Keiley added, “Especially by either the ignorance of the malice of the chief,” referring to Dr. Eugene Sanger, Elmira’s chief surgeon.[v]

Keiley had a special hatred for Sanger, who he described as “a club-footed little gentleman, with an abnormal head and a snaky look in his eyes.” In the prisoner’s estimation, the chief surgeon was cold and callous with an abiding dislike of rebel soldiers.[vi]

Much of the illness in Elmira Keiley and Dr. Sanger both ascribed to the unhealthy conditions created by Fosters Pond – a body of still water inside the camp that quickly became contaminated with excrement and other pollution. “The miasma from the lagoon,” Keiley remembered, “sowed the seeds of febrile disease so widely, that eight or ten hospitals had to be built.”[vii]

On September 29, Col. Tracy, the post commander, received from Col. Hoffman, the Union commissary general of prisoners, orders stipulating that “invalid prisoners of war in your charge who will not be fit for service within sixty days will be in a few days sent South for delivery to the rebel authorities.” They would prepare careful duplicate rolls and take appropriate measures for the security and well-being of the prisoners. But, Hoffman warned, “None will be sent who wish to remain and take the oath of allegiance, and none who are too feeble to endure the journey. Have a careful inspection of the prisoners made by medical officers to select those who shall be transferred.”[viii]

Grant’s revival of the prisoner exchange at this stage is interesting. Just months earlier, he had been vehemently opposed to the exchange because Confederate authorities refused to exchange black soldiers and from a knowledge that men on parole would be right back in the ranks of the Southern armies. This last point helps to explain why only the sick unable to return to service in sixty days would be exchanged. Perhaps Grant, aware of the extent of suffering of prisoners in northern and southern camps, wanted to make a humanitarian gesture and relieve the unfortunates wasting away. Or, with Lincoln’s re-election in mind, the general-in-chief offered a political move.

Anthony Keiley, cynical as always, reacted strongly to the news of the renewal of exchange. Disappointed that he would not be among those going home, perhaps he vented his frustration as he reflected on the circumstances. “Having beat up England, Ireland, Scotland, France, German, Switzerland, Asia and Africa for recruits, these invincible twenty millions of Yanks admit that they still are not a match for five millions of Southerners, and they cling with the tenacity of death to every able bodied “reb” they can clutch, lest he may again enter the Southern army.” In the end, Keiley actually joined those sent South. As a parting reward from Maj. Colt, whom Keiley highly admired, the Virginian served as an escort and nurse for his ailing brethren on the journey.[ix]

One of the fortunate ones, Keiley left Elmira before winter set in. Snow came soon after and the hundreds of prisoners still housed in tents shivered on the frozen ground. Exchanged late that fall, Keiley returned to Petersburg to resume his life as the Confederacy lurched into its final winter.

Following the war, Keiley resumed both his journalism and political careers. The former would ultimately lead to his arrest. As editor of a newspaper simply titled “The News”, Keiley was unsparing in his condemnation of Union occupation in Virginia. “In its columns Keiley attacked the military authorities in power in Virginia with such vigor and bitterness that the paper…was suppressed” and he was incarcerated again in Castle Thunder, a former prisoner of war facility which the Confederacy used to house Union soldiers, in Richmond.[x]

Keiley’s political career accelerated in 1870 when he was elected mayor of Richmond, a post he retained until 1876. Later when Democrat Grover Cleveland was elected president, the Virginian was appointed to diplomatic posts in both Italy and Austria-Hungary. But when the New York Herald published statements Keiley had made critical of King Victor Emmanuel, in an effort to embarrass the Cleveland administration, both countries declined to host him and Keiley was forced to resign both posts. As a kind of consolation prize, Cleveland appointed Richmond’s former mayor to the International Court at Cairo. There the Virginian served for a number of years without incident.

Anthony Keiley died in 1905 in Paris, France, following an accident in which he was hit by a motor vehicle. He was 72.

For those interested in learning more about Anthony Keiley and the many other inmates of the Elmira POW camp, pick up a copy of Emerging Civil War’s newest title, Hellmira: The Union’s Most Infamous Civil War Prison Camp – Elmira, NY.

————

Portions of the text are from Hellmira: The Union’s Most Infamous Civil War Prison Camp – Elmira, NY. (Savas Beatie, 2020).

[i] James H. Bailey, “Anthony Keiley and the “Keiley Incident.’” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 67, no. 1 (January 1959) 65-81.

[i] Keiley first wrote Prisoner of War, or Five Months Among the Yankees. Being a narrative of the crosses, calamities, and consolations of a Petersburg militiaman during an enforced summer residence north – which he wrote as “A. Rifleman.” In 1866, Keiley revised this work and expanded it into In Vinculis; or, The Prisoner of War. Being, The Experience of a Rebel in Two Federal Pens, Interspersed With Reminiscences of the Late War; Anecdotes of Southern Generals, Ftc. 62.

[ii] Anthony M. Keiley, In Vinculis; or, The Prisoner of War. Being, The Experience of a Rebel in Two Federal Pens, Interspersed With Reminiscences of the Late War; Anecdotes of Southern Generals, Ftc. (New York: Blelock & Co., 1866) 62.

[iii] Keiley, In Vinculis, 131.

[iv] Ibid, 132.

[v] Ibid, 174.

[vi] Ibid, 138.

[vii] Ibid 131.

[viii] OR, series II, vol. VII: 894.

[ix] Keiley, In Vinculis, 180.

[x] Bailey, “Anthony Keiley”, 69.

Interesting article; thanks for posting.

Another 12th Virginia Infantry writer from Keiley’s company (E, the Petersburg Riflemen), was Sgt. Leroy Summerfield Edwards, whose letter collection is at Randolph-Macon College in Ashland, Virginia with a copy at University of Georgia, in Athens, Georgia. Edwards was educated at Randolph-Macon. During the winter of 1863-1864 he was in the same Bible study group as Pvt. George S. Bernard of the Riflemen, who later compiled and edited “War Talks of Confederate Veterans” (1892) and compiled a sequel that was ready for publication in 1896 but disappeared until 2004, when it was purchased in a flea market for $50, sold to a museum for $15,000 and edited into “Civil War Talks: Further Reminiscences of George S. Bernard & His Fellow Veterans” (2012) by Hampton Newsome, John Horn and John Selby. Keiley figures in “An Affair with Cavalry” in “Civil War Talks,” an account of Second Brandy Station (Aug. 1, 1863) by the 12th’s Adjutant, Capt. William Evelyn Cameron, after the war Governor of Virginia. It’s all in “The Petersburg Regiment in the Civil War: A History of the 12th Virginia Infantry from John Brown’s Hanging to Appomattox, 1859-1865” (Savas Beatie, 2019).

Great Article! I have to say though that I’m very concerned for the prison cemetery down there. I pray it doesn’t get vandalized and it’s sad to say but I could honestly see people wanting it dug up and the remains repatriated to their respective states.