Unintentional Reconciliation – Memorializing the Cavalry Fight at Gettysburg

Though not far from the Civil War’s memorial epicenter, the cavalry battlefield at Gettysburg National Military Park sits relatively undisturbed by the crowds of tourists who come to see the site of the largest ever battle in the Western Hemisphere. Nearly every automobile, bicycle tire, and hiking boot that sets foot on the present-day battlefield eventually finds its way to the copse of trees and the monument to the High Water Mark of the Rebellion. There they find several artillery pieces, a small grove of trees, and an open bronze book—a monument that has guided thousands of visitors to the mistaken impression that the defeat of George Pickett and his Virginians (and J. Johnston Pettigrew and Isaac Trimble and their North Carolinians) meant the defeat of the Confederacy and that Gettysburg was the war’s great turning point.

The high water mark is an example of a monument that pays tribute to both of the armies that fought in Adams Country, Pennsylvania, for three days in early July, 1863. It is a monument to a memorial tradition that Civil War historians have termed reconciliation: the efforts of the wartime generation and their descendants to “let bygones be bygones” and work toward the reunification of the country in the aftermath of the war (the open bronze book devotes a page each to “the assaulting column” and “the repulse of the assault”). Many historians have understood this phenomenon as an effort on the part of white veterans, both Union and Confederate, to erase African American participation in the war and its memory (see especially David Blight, Race and Reunion [Harvard: 2001] and Gaines M. Foster, Ghosts of the Confederacy [Oxford: 1985]). Others have questioned the degree to which the wartime generation truly invested in reconciliation, notably Caroline E. Janney, whose Remembering the Civil War [UNC Press: 2013] argues that reconciliation was never the favored memorial tradition of veterans—who embraced reunion as a more limited goal and strove to effect the political reunification of the nation, rather than a social or cultural reunification with their former foes.

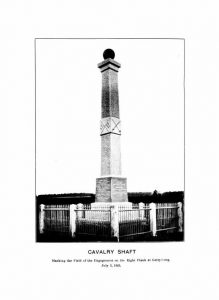

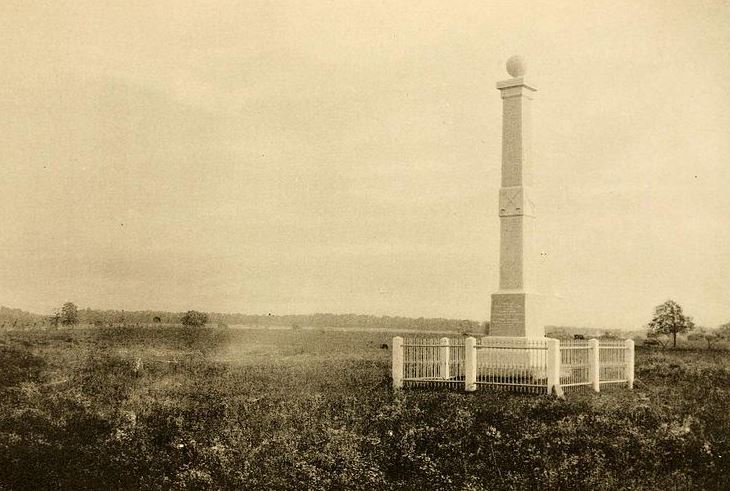

The high water mark received its monument in 1892—an early monument to reconciliation, to be sure, but it was not the earliest to appear on the battlefield. Rather than celebrating one of the battle’s most famous actions, the first reconciliation monument at Gettysburg recalled the service of the Union cavalrymen who fought under Brig. Gen. David McMurtrie Gregg against the late-arriving Confederate cavalry commanded by Maj. Gen. James E. B. “Jeb” Stuart on July 3, 1863. Erected on October 15, 1884, the Gregg monument does not receive the thousands of visitors who clamber to Hancock Avenue to imagine the Confederate charge from Seminary Ridge toward the Angle. In order to view the obelisk, visitors must find their way due east from Gettysburg, almost to the point where the modern Gregg Avenue meets the wartime Low Dutch Road. Once there, they must avoid the temptation of the monument to George A. Custer and his Michigan Wolverines, park their vehicles, and walk some 150 yards back from the road, where they will encounter a twenty-nine foot tall shaft of New Hampshire granite, surrounded by a modest wrought iron fence.

The high water mark received its monument in 1892—an early monument to reconciliation, to be sure, but it was not the earliest to appear on the battlefield. Rather than celebrating one of the battle’s most famous actions, the first reconciliation monument at Gettysburg recalled the service of the Union cavalrymen who fought under Brig. Gen. David McMurtrie Gregg against the late-arriving Confederate cavalry commanded by Maj. Gen. James E. B. “Jeb” Stuart on July 3, 1863. Erected on October 15, 1884, the Gregg monument does not receive the thousands of visitors who clamber to Hancock Avenue to imagine the Confederate charge from Seminary Ridge toward the Angle. In order to view the obelisk, visitors must find their way due east from Gettysburg, almost to the point where the modern Gregg Avenue meets the wartime Low Dutch Road. Once there, they must avoid the temptation of the monument to George A. Custer and his Michigan Wolverines, park their vehicles, and walk some 150 yards back from the road, where they will encounter a twenty-nine foot tall shaft of New Hampshire granite, surrounded by a modest wrought iron fence.

The “Gregg Cavalry Shaft,” was erected with money raised by the survivors of the Third Pennsylvania Cavalry. In the proposal that the Union veterans made to the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association in April 1864, the survivors of the cavalry fight expressed their wish to place a monument “with suitable inscriptions” on the cavalry field.[1] Within sixth months, the veterans had settled on their inscription—and created the first monument on the battlefield that listed both the Union and Confederate units that met in battle–and in particular, on the fields surrounding John and Sarah Rummel’s farm. For this reason the monument has often been noted as the first at Gettysburg to feature “reconciliation” as a central theme.[2] The text below is featured on the four panels at the monument’s square base.

This shaft

marks the field of the engagement

between the

Union Cavalry

commanded by Brig. Gen. D. McM. Gregg

and the

Confederate Cavalry

commanded by Maj. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart.

July 3d, 1863.Union Forces

1st Brigade, 2d Cavalry Division, Col. J. B. McIntosh;

3d Penna. Cavalry, Lt. Col. E. S. Jones.

1st New Jersey Cavalry, Maj. M. H. Beumont.

1st Maryland Cavalry, Lt. Col. J. M. Deems.3d Brigade, 2d Cavalry Division, Col. J. Irvin Gregg;

16th Penna. Cavalry, Lt. Col. J. K. Robison

4th Penna. Cavalry, Lt. Col. W. E. Doster

1st Maine Cavalry, Lt. Col. C. H. Smith

10th New York Cavalry, Maj. M. H Avery.1st Mass. Cavalry, Lt. Col. C. S. Curtis;

Purnell Troop A, Md. Cavalry.

Co. A. 1st Ohio2d Brigade, 3d Cavalry Division, Brig. Gen. G. A. Custer;

1st Mich. Cavalry, Col. C. H. Town

5th Mich. Cavalry, Col. R. A. Alger.

6th Mich. Cavalry, Col. Geo. Gray

7th Mich. Cavalry, Col. W. D. Mann.Union Artillery

Randol’s Light Battery E, 1st U.S. Artillery.

Pennigton’s Light Battery M, 2nd U. S. Artillery

2nd Sec. Light Battery H, 3d Penna.Confederate Forces. Cavalry.

Hampton’s Brigade, Brig. Gen. Wade Hampton

Fitz Lee’s Brigade, Brig. Gen. Fitz Hugh Lee

Jenkin’s Brigade, Col. M. L. Ferguson

W.H.F. Lee’s Brig., Col. J. R. Chambliss.Artillery.

McGregor’s Virginia Battery

Breathed’s Maryland Battery

Griffin’s 2d

While the monument certainly appears to promote the idea of reconciliation to modern visitors—and holds the distinction of being the first to include both Union and Confederate commands—it is more difficult to determine whether the veterans who promoted the memorial intended their monument to reach out a hand to their former foes. My view of the Gregg Monument is that its history very much supports the arguments made by Caroline Janney—it was not a purposeful paean to reconciliation, it has simply been read in that spirit in the decades since its appearance on the battlefield, especially by subsequent generations eager to create a narrative of the Civil War that suits their contemporary moment. The Union veterans who oversaw the monument’s erection seem to have only inscribed Confederate names in order to give an accurate history of the oft-ignored cavalry fight. The speeches given at the monument’s dedication underscore this attitude, along with later reflections in regimental histories of the Union units who participated in the fight.

In his dedicatory address on October 15, 1884, Col. William Brooke Rawle was explicit about who the cavalry shaft was designed to celebrate. Rawle began his speech by asking the assembled veterans to recall their “sacrifices made in defense of the Nation’s cause.” He then recounted the reasons for the Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania, the first two days of the fight at Gettysburg, and, finally, the Union cavalry’s defense of the army’s right flank against Jeb Stuart’s Confederate troopers on the final day of the battle. Rawle then explained that Stuart claimed to have driven the Union cavalry from the field “thus insinuating that he was the victor of the fight,” and added, with some sharpness, “other Confederates are now doing likewise.” Rawle had little patience for this attitude, which he believed perverted the results of the Union cavalry’s defense of a critical part of the battlefield. Rawle made clear that there was no love lost between the disingenuous Confederate veterans and the “brave men, our companions in arms, who here poured forth the full measure of their lives’ devotion for the Cause they loved.” Rawle delivered a speech that was firmly rooted in the Union memory of the war, and which adopted no visible tone of reconciliation. If anything, the former cavalrymen still harbored animosity toward former Confederates, who were, he believed, propagating a false narrative of the battle.[3]

In the regimental history of the Third Pennsylvania Cavalry, published in 1905, Rawle maintained his pro-Union perspective. Reflecting with a clear sense of pride on the existence of the Gregg monument, Rawle wrote “the shaft can be distinctly seen from East Cemetery Hill from which point the greater part of the entire battlefield is visible. From that position the relative importance of the cavalry fight can best be judged.” Rawle’s reminiscence indicates that he and his fellow veterans hoped their monument would work to bring attention to the cavalry battle, which had long been overshadowed by the infantry fighting on the Union center on July 3.[4] Rawle gave no indication is his unit history that anyone involved with the monument’s creation intended to give attention to the Confederates in equal measure with the Union troops.

While Rawle’s lifetime of advocacy for the Union cavalry’s importance to the victory at Gettysburg offers only one perspective on the monument, there was no single individual more involved with the creation and erection of the Gregg Cavalry Shaft. Rawle left a clear account of the monument’s history across a period of three decades that made no mention of reconciliation—and, in fact, did little to promote reconciliation among his contemporaries and the survivors of the cavalry fight. While the monument stands today as a record of the participation of both Union and Confederate cavalrymen in the battle of Gettysburg, it is important to look at the history behind the inscriptions and consider monuments from the perspective of those who designed them. Doing so allows us to see how history and meaning are layered onto the landscape—and offer a reminder of the value of monuments for understanding how history and memory overlap and clash—an important lesson for the current moment, as we reflect on the 157th anniversary of the battle of Gettysburg.

ECW contributor Daniel Davis has also written about the cavalry fight here.

________________________________

[1] John M. Vanderslice, Gettysburg Then and Now (New York: G. W. Dillingham Co., 1897), 371.

[2] See, for example, Carol Readon and Tom Vossler, A Field Guide to Gettysburg (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 392.

[3] William Brooke Rawle, “Gregg’s Cavalry Fight at Gettysburg,” Journal of the U. S. Cavalry Association 4 (September 1891): 257-75.

[4] William Brooke Rawle, History of the Third Pennsylvania Cavalry, Sixth Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers in the American Civil War, 1861-1865 (Philadelphia: Franklin Printing Company, 1905), 556.

A lot of wind with very little sail. Reflected much more of the author’s viewpoints filtered through the ponderous Mr Blight than anything the soldiers actually were thinking. Most soldiers were too busy getting on with their lives after the war to do much profound thinking about reconciliation save as a very peripheral sidebar.

Hi John! Thanks so much for reading my piece. I just wanted to note that I hold with Dr. Janney and not Dr. Blight, and my point is that veterans were not thinking about reconciliation — as you suggest!

“In order to view the obelisk, visitors must find their way due west from Gettysburg”…Small typo here, East Cavalry field and the obelisk would be east of Gettysburg.

I urge everyone to read the actual speech referenced in the article. Google “Journal of the U. S. Cavalry Association 4”. It will take you about 15 minutes to read. The spin the author puts on the speech, and what was actually said by Col. Rawles, have little in common.

As far as the unit history, I have not read it. Did Col. Rawles write that the history would be about reconciliation, either for or against? Was that intended to be the theme of the unit history of the 3rd Pa. Cavalry Regiment? If not, then how can he be criticized for not discussing it? That would be like reading a book on the Battle of the Marne and then criticizing the author for not discussing the ramifications of the Treaty of Versailles.

Hi Bolts,

Thanks for reading my piece!

I’m not condemning Rawle for not talking about reconciliation. My point is that the Cavalry monument is often designated a reconciliation monument (especially in modern battlefield literature) and when we look in the sources (like the speech and the regimental history) the men who designed and dedicated the monument did not intend for it to be about reconciliation. I’m relying on Rawle to point out that as a Union veteran he cared about Union victory and wanted the veterans who he served with to get some recognition for their efforts during the battle. That’s how I read his speeches and writing.

I appreciate the comment, however, and will work on refining how I present my argument.

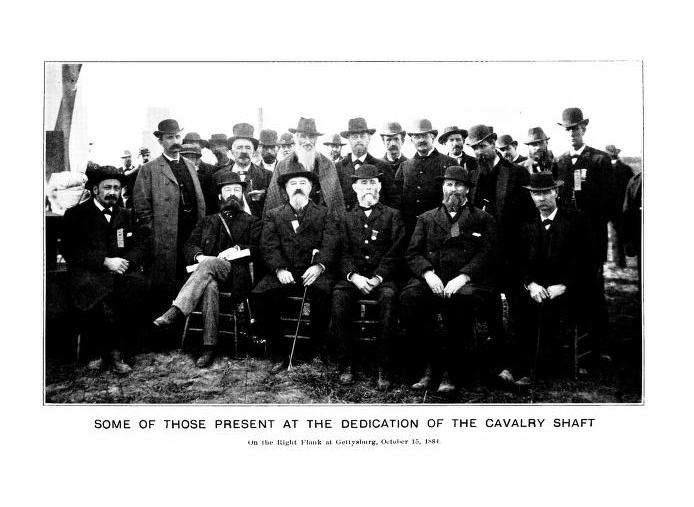

The officer sitting on the far left is William E. Miller of the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry, not William F. As you know, Captain Miller led his squadron in the famous charge into the flank of the enemy. Brooke-Rawle served under Miller in the regiment and after the war lobbied for Miller to receive the Medal of Honor, which was awarded to Miller in 1896.