Damned Green Yanks: The 171st Ohio at Keller’s Bridge, Kentucky

ECW welcomes back guest author Dan Masters

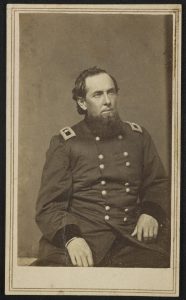

The morning of June 9, 1864 began like many mornings at the prisoner of war camp on Johnson’s Island near Sandusky, Ohio. Sea gulls flew over the camp as redwing blackbirds added their picturesque trills to the sounds of waves lapping against the shore. Surrounded by the placid waters of Sandusky Bay, the camp guards belonging to the 171st Ohio started their duty day with guard mounting, then morning drill. Colonel Joel F. Asper, a discharged wounded veteran of the 7th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, endeavored to ensure that his regiment of 100-days’ men was as well-drilled as any regiment in the service. The regiment was barely a month old, having been created by consolidating four understrength battalions of Ohio National Guardsmen from Trumbull, Portage, Lake, and Geauga Counties of northeast Ohio. Called into Federal service, eight companies of the regiment totaled 876 men were assigned to the duty, along with the 128th Ohio, of guarding the more than 1,000 Confederate prisoners of war housed within the stockade walls on Johnson’s Island. It was an enchanting location coupled with a dull assignment; a safe sinecure from the ravages of a war that was entering its fourth summer.

“A portion of the daily duties had already been performed when a rumor, vague at first and exciting no particular attention, was circulated to the effect that marching orders had been received,” recalled Sergeant George N. Hapgood of Co. A. “Soon an order was issued for all extra baggage to be packed for sending home and knapsacks packed for any emergency. About 9 o’clock, the regiment was ordered to be ready with four days’ cooked rations to move about 3 p.m. The men, under the impression that the island was to be their station during the 100 days, had surrounded themselves with many conveniences and many a hard day’s toil had contributed to beautify their camp. Packing had scarcely commenced when another order was received restricting their time to about one hour. The rations could not be cooked; many men had only time, after disposing of their baggage and dropping a few lines home, to provide themselves with a few hard tack and a little raw pork. About noon, the regiment was at the landing, waiting for a boat to take us across the bay.” [1]

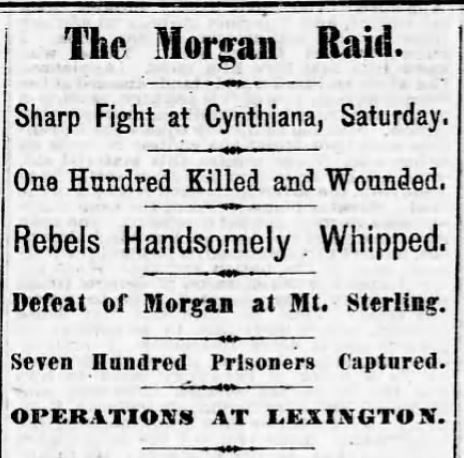

The cause of the 171st Ohio’s rapid departure was a familiar one to the Buckeyes: their old nemesis, Confederate cavalryman General John Hunt Morgan was raiding again in Kentucky. Major General Samuel P. Heintzelman commanded the Northern Department and was closely watching developments in Kentucky. It became clear that reinforcements were needed rapidly in northern Kentucky to safeguard various Union outposts and the 171st Ohio, being one of the few regiments within the Northern Department, drew the assignment.

“As our beautiful camp in the grove receded from our view, many eyes were cast toward it but not a murmur was heard,” wrote Sergeant Hapgood. “On reaching Sandusky, we found the 24th Ohio Battery, which had been stationed near that point, preparing to move with us. A good deal of time was consumed in making up the trains and about 4 o’clock we turned our faces southward. We were closely packed in freight cars with no ventilation, a defect which the butts of some of the muskets soon remedied. Our first night out passed anything but pleasantly. The sleeping arrangements were far from commodious or comfortable, and many a wish was uttered for the little tents of our camp. Indeed, but little sleep visited the eyes of the men. During the night, the battery left us for some point in Indiana, a fact we afterwards sincerely regretted.” [2]

“We reached Cincinnati about noon [June 10], unloaded, slung knapsacks, marched to the Ferry, and crossed to Covington,” Hapgood reported. “We stored everything there except our blankets, drew dog or shelter tents and painted [rubber] blankets, each man carrying his own outfit. At this point were a few of the 47th Kentucky, and some others, numbering altogether 200-300 men. For this latter force, fresh horses, new saddles, bridles, and accoutrements were drawn to enable them to act as cavalry. In loading the horses on the cars, a stampede occurred, and a number of the frightened animals rushed madly along the street in which the 171st had just been formed in line. It was so dark that they were not seen until just upon us, and it is a wonder that more were not injured.” [3]

Brigadier General Edward H. Hobson had command of the Federal forces at Covington and decided to send this scratch force further south along the railroad line in hopes of either trapping Morgan’s cavalry or securing the railroad from further damage. The latest intelligence reports had placed Morgan’s cavalry between Lexington and Georgetown and indicated that the Kentucky Central Railroad was clear of guerillas. Hobson ordered his force south on two trains: the first carried roughly 600 men from the 171st Ohio while the second train of twenty cars carried 200 Kentuckians (home guards and regular regiments) along with roughly 250 horses; as an attack was considered possible, sentinels were placed atop every car.[4]

“Our second night was not much of an improvement on the first. We were packed this time in cars designed for shipping horses, and although better ventilated than those occupied the preceding night, we were so closely packed that sleep, to many, was out of the question,” complained Hapgood. “We got off about 10 o’clock [p.m. June 10] and reached a point known as Keller’s Bridge about daylight [June 11]. [Keller’s Bridge, a railroad trestle over the South Fork of the Licking River, was located 1-1/4 miles north of Cynthiana, Kentucky, a small town about 65 miles south of Cincinnati located along the Kentucky Central Railroad.] The bridge and blockhouses had been burnt by Morgan’s men on Thursday [June 9] and the ruins were still smoking. The horses were about being unshipped and accoutered when firing was heard in the distance and we were immediately ordered to fall in line.” [5]

Private Ephraim F. Jagger of Co. I described the scene upon the regiment’s arrival at Keller’s Bridge. “The train stopped within 15 rods of the burnt bridge and our force on emerging from the cars could plainly discover the scouts of the Rebs on the hills that lay on the right and left of the track to the height of 30 or 40 feet,” he wrote. “On the right of the train as it stopped was a ravine running up to the railroad valley by the side of which was a small fence and quite a number of bushes from behind which the Rebs sent out a hot and deadly fire upon our troops.” Companies C, F, and H deployed on a hill to the west of the railroad; skirmishers pushed forward from this line and Companies D and I relieved this line during the ensuing engagement. A stone wall at the corner of the river, road, railroad and hill was occupied by Co. B throughout the fight. “Companies A and G were sent up the right of this ravine. The hill on the left of the train was where the troops first formed and was a beautiful open pasture rising with a gradual slope to the summit which was occupied by a few large scattering trees and in the rear lay a road and rye field with clumps of trees extending down to the river; this extended from the railroad bridge around the base of the hill here to the railroad track in almost a semi-circle,” Jagger stated. [6]

General Hobson deployed his men in a precarious spot within an oxbow of the South Fork of the Licking River. By stopping the train so close to Keller’s Bridge, Hobson’s Federals walked neatly into a trap which Morgan’s cavalrymen rushed quickly to spring. With a total of 800 men under his command, Hobson (unknowingly) was confronted by nearly twice as many veteran Confederates. Colonel Asper had been ordered to detail 230 men to saddle the horses and get them off the train when he heard firing. It was the fight between the 168th Ohio and Morgan’s command. Hapgood reported “they were soon captured, and between 5 and 6 o’clock [a.m.], a portion of the 47th Kentucky which had been sent out as skirmishers on foot came upon a party of Rebels each with a number of horses in charge, their riders having dismounted to follow the bushwhacking style of fighting. They immediately gave them a volley, scattering them in all directions.” [7]

Whitelaw Reid described the battle. “Upon arriving at Keller’s Bridge, the regiment debarked and one company went on picket [Co. C]. While ammunition and rations were being issued and the horses taken from the cars, firing was heard at Cynthiana and about this time, Sergeant Major William H. Blandin of the 168th Ohio came up and reported that Colonel Conrad Garis [168th Ohio] at Cynthiana was attacked by General Morgan’s entire command. Colonel Garis requested Colonel Asper to come to his assistance and he would hold out if possible.” Colonel Asper quickly formed his men and was about the move when General Hobson arrived, and the Confederates attacked.[8] “A large column of cavalry was coming down the road toward us, for the purpose of between us and Colonel Garis or to get to Colonel Garis’ rear. I placed two companies under the command of Major Manning Fowler on the point of a hill across the railroad,” Asper wrote. “These companies opened fire upon the column immediately and drove it back, several saddles being emptied at the first fire.”[9]

The Kentucky cavalrymen, reinforced by Co. C, started to fall back under Confederate pressure from Cynthiana. “Both parties were gradually closed in upon and compelled to fall back and were in great danger of being cut off,” Jagger wrote. “But at this time Co. F and Co. H formed on the top of the hill in line of battle and opened on the pursuing enemy and brought them to a stand by the fierce fire of 10-12 rounds. Company I then took their place while they retired to the cover of the hill and occupied the top protected by the scattering bushes that grew near its summit on the side next to the river.” [10] It was quickly evident that the 171st Ohio was outgunned; Morgan’s men carried Enfield rifles or various carbines while Asper’s men carried old .69 muskets. Captain Richard Swindler of Co. B complained that the 171st Ohio “was armed badly, many of the pieces failing to reach the enemy at all; very many became useless early.” General Morgan apparently also didn’t think highly of their guns as “many of the arms were burned on the field by Morgan’s order as worthless, and the others put into the hands of his unarmed recruits.” [11]

“We were compelled to fall back to the cover of the bushes on the brow of the hill and loaded and fired as we could by finding targets peeping over the hill,” Jagger related. “Captain Cyrus Mason charged us to save our fire and use our ammunition carefully and not needlessly expose our position. Here we fought for over three hours and the efforts of the enemy to dislodge us from our position most signally failed. The Rebels sullenly retired to await reinforcements that were ordered up with [General] Morgan at their head. A stone wall at the foot of the hill furnished cover for Co. B and scattering reliefs for the skirmishers and pickets and a deadly fire was kept up which prevented the enemy from getting in our rear or our right down the railroad track.”[12]

“The hill on which Colonel Asper and General Hobson and staff stood was terribly swept by a fire from Rebel sharpshooters and from the woods towards their right,” Jagger wrote. “A number of good marksmen behind some large trees near the officers’ position kept the Rebs at bay.”[13] Colonel Joel Asper’s “portly frame” was a conspicuous mark on the battlefield Hapgood remembered.[14] Jagger noted that once the Confederate reinforcements arrived, they quickly moved to surround the Union position “They filed in column in our rear and on the right and front of our original position and so completely surrounded us.”[15]

“The National position was invested in front, flank, and rear, and the Rebels demanded a surrender,” Whitelaw Reid reported. “As resistance was useless, the demand was acceded to with the understanding that all private property except the officers’ horses should be unmolested. When General Morgan arrived, he altered the terms and allowed the officers to retain their horses, but a Rebel colonel had taken a fancy for Lieutenant Colonel Heman R. Harmon’s horse and insisted on keeping it and finally did so, giving Harmon one much inferior to his own. In this fight, the regiment lost 13 killed and 54 wounded.” In addition, another 680 men were captured. The 168th Ohio lost 7 killed, 18 wounded, and 280 prisoners in their fight at Cynthiana. [16]

Sergeant Hapgood was convinced that had the 171st Ohio arrived a few hours sooner they could have formed a junction with the 168th Ohio, and Morgan would have elected to forego attacking or the Federals would have held their position. Regardless, he reported that Morgan’s men complimented the Buckeyes on their stand at Keller’s Bridge. “Damned green Yanks, didn’t know when they were whipped,” quipped one trooper.[17] Private Jagger complained that most of Morgan’s men followed the terms of the surrender, “when one of our men was alone out of sight of his or our officers, they proceeded to demand watches, money, hats, blankets, and haversacks, and enforced the demand by the presentation of a revolver or gun to the breast of the victim. Several of our men were thus robbed.” [18] A slight measure of revenge took place a week or so later when one of Morgan’s paroled staff officers met a member of the 171st Ohio in front of the Dennison House in Cincinnati. “He halted the Rebel with an oath and said ‘You took my gun from me at Cynthiana and abused me; it is now my turn,’ and then knocked him down and kicked him into the gutter, and walked on.”[19]

“We were marched to the top of the hill just above the point where we first formed on leaving the cars, stacked our arms, and marched down the hill and over to the city of Cynthiana,” Jagger continued. “The smoking ruins of the business portion of the city and torn and rifled contents that had been thrown out on the ground bore sad testimony of the horrors and devastation of the contest. We were marched to a grove a short distance south of the place where our names and numbers were taken by order of General Morgan.”[20]

Sergeant Hapgood continues. “The whole number of prisoners was marched about three miles on the Augusta Pike [now US Highway 62] and turned into a grass field where we spent our third night,” wrote Hapgood. “Uncomfortable as had been the others, we would have gladly exchanged our present for previous accommodations. The day had been warm and during the fight most of the men had dropped their blankets and haversacks which were not afterwards seen. The night was cold with a very heavy dew. We were tired, cold, and hungry. What few rations we saved were divided among some prisoners of the 12th Ohio Cavalry who had been taken at Mount Sterling on Thursday last and marched over 100 miles with scarcely nothing to eat.” [21] Jagger recalled that the Federal prisoners discovered that nearly all of them lacked blankets, and that Morgan’s men had taken the coats and shoes from the 168th Ohio. “Fires were commenced by the prisoners early in the evening but almost as soon and order came to put them out,” Jagger wrote. “In spite of the orders, a long line of fence rails disappeared and several fires burned brightly, bearing witness to the fact that many thought prisoners were not subject to orders. Some that had tea or coffee boiled it and diving deep into their haversacks drew up a few crumbs of hard tack to mix with it and in this satisfied the claims of empty stomachs.”[22]

General Morgan now had upwards of 1,350 Federal prisoners on hand and with General Burbridge in hot pursuit with 2,400 Union cavalry, the question became what to do with them. “After the surrender, Morgan proposed to send General Hobson and staff, Colonel Asper, Lieutenant Colonel Harmon, and Major Manning Fowler to communicate with the military authorities for the purpose of effecting an exchange. These officers gave their parole to go under the escort of three Rebel officers to the nearest point where communication could be had by telegraph and there effect an exchange, and in case of a failure of their negotiation, to return as soon as practicable by the nearest route. The party reached Falmouth [Kentucky] Sunday evening June 12th, and opened communication with General Burbridge, commanding the District of Kentucky and after a few days’ delay, ordered General Hobson and staff to Lexington for duty, directing him at the same time to take the Rebel officers with him as prisoners of war and ordered the Ohio officers to Cincinnati,” Reid stated.[23]

General Morgan now had upwards of 1,350 Federal prisoners on hand and with General Burbridge in hot pursuit with 2,400 Union cavalry, the question became what to do with them. “After the surrender, Morgan proposed to send General Hobson and staff, Colonel Asper, Lieutenant Colonel Harmon, and Major Manning Fowler to communicate with the military authorities for the purpose of effecting an exchange. These officers gave their parole to go under the escort of three Rebel officers to the nearest point where communication could be had by telegraph and there effect an exchange, and in case of a failure of their negotiation, to return as soon as practicable by the nearest route. The party reached Falmouth [Kentucky] Sunday evening June 12th, and opened communication with General Burbridge, commanding the District of Kentucky and after a few days’ delay, ordered General Hobson and staff to Lexington for duty, directing him at the same time to take the Rebel officers with him as prisoners of war and ordered the Ohio officers to Cincinnati,” Reid stated.[23]

“Early on Sunday morning [June 12], we were hurried off and marched over a newly macadamized road about 15 miles which we made in four hours, fording the North Licking River and traveling over a very hilly country,” Hapgood related. “A large portion of the way was on the double-quick, the constant ‘close up, men’ of the mounted guard ringing in our ears. It was evident to us that something was in the wind, as thus far we had received courteous treatment at least from the officers.” [24] After marching 24 miles and halting near Claysville, Morgan called the captured officers together and proposed to parole the prisoners if they would agree not to try and escape. Upon their acceptance of these terms, Captain Evan Morris of Co. D was directed to mount a horse by Morgan’s inspector-general and “compelled to ride along the lines with him, and he then told the men they were paroled, administering to them some oath, or some sort of obligation.” [25]

“The oath of parole was administered to us by Colonel Greenwood, Rebel officer of the day,” Jagger stated. “So closely were the Rebels pursued by our cavalry that the Rebel cavalry formed in line of battle in the rear of the prisoners.”[26] Hapgood wrote that “an escort was promised to Augusta, but after turning us off the main pike and marching us three or four miles out of our course, we were again halted, the whole gang filed past us, and disappeared in an eastern direction.” [27]

“It was now after noon and we had a march of 22 miles before us in order to reach Augusta,” Hapgood wrote.[28] “On and on we went, the sharp stones made our feet sore and our limbs almost refused to obey our will. But there was no place to stop unless we took the ground again with nothing to eat. The region was sparsely settled and only two small villages were passed, Milford and Brooksville, and all the food that could be purchased served only to whet the appetites of a few in the extreme front. Suffice it to say, that the march of least 40 miles was made. The main portion reached Augusta about dark. We were disheartened at our defeat and unused to marching; it was truly a day that tried our souls. What will become of us, I cannot tell? Many of us were aware that the parole, under the circumstances, was of no account. Indeed, Morgan himself said that he depended more on our own honor than the legality of the form.” [29]

After reaching Augusta, the 171st Ohio was reformed, placed on boats, and returned to Covington, Kentucky. It was reunited with the two companies left behind at Camp Dennison and soon was on the rails heading north. However, its fight at Keller’s Bridge won renown for the regiment. The citizens of Falmouth and Covington publicly thanked the men, and the Cincinnati Gazette opined that “there is little doubt that the stubborn resistance of the 171st Ohio saved Cincinnati from visitation.” Governor John Brough, General Heintzelman, and General Hobson told Colonel Asper of their gratification for “the bravery and courage displayed by the regiment.” Regardless of the praise, for the 171st Ohio, the parole by John Hunt Morgan meant a one-way ticket back to the monotony of guarding Confederate prisoners of war on Johnson’s Island for the balance of their 100-days’ service. [30]

The regiment arrived back on the island but under the terms of their parole, they stayed in camp and did not perform any guard duty. In a few weeks, a communication from the War Department declared their parole null and void, allowing the regiment to return to duty. The regiment’s experience with being captured softened the hearts of some to the plight of the Confederate prisoners of war. “It certainly looks hard to see these men caged up,” confessed one soldier. “We earnestly wish it could soon be otherwise for notwithstanding the bitterness with which we despise them as enemies and traitors, a feeling of sympathy steals over the sentinel as he paces the fence.”[31] The sight of the 171st Ohio returning to guard duty didn’t set well with some of the Confederate prisoners, particularly those of Morgan’s command. “Some indications of insubordination among the prisoners was noticed, there being now confined here several of Morgan’s officers with whom the 171st was engaged and were taken by [General] Burbridge. They didn’t like the idea of being guarded by men whom they had paroled,” recounted Sergeant Hapgood. “The consciences of our boys have been quieted on that score, however, by the order from proper authority and they not only felt perfectly competent, but very willing to take care of the ‘bull pen’ in any emergency.” The men also felt confident because upon returning to duty, they had been issued new Enfield rifles, a far cry from the old muskets they carried into battle at Keller’s Bridge. [32]

[1] Hapgood, George Negus. “Four Days’ Experience of the 171st Regiment,” Western Reserve Chronicle (Ohio), June 22, 1864, pg. 2. Hapgood worked as the editor of the Western Reserve Chronicle in Warren, Ohio, and as a member of the Ohio National Guard, had taken a 100-day break from his editorial duties to serve with the 171st Ohio when his local company was called into service.

[2] Hapgood, op. cit. Upon arrival at Cincinnati, Companies E and K were detached from the regiment and left at Camp Dennison; this reduced the total strength of the regiment to roughly 500 men.

[3] Hapgood, op. cit. The regiment also drew 30,000 rounds of ammunition and two days’ rations while in Covington.

[4] Reid, Whitelaw. Ohio in the War: Her Statesmen, Generals, and Soldiers. Volume II: The History of Her Regiments and Other Military Organizations. Cincinnati: The Robert Clarke Co., 1895, pg. 701. General Hobson complained that the 168th Ohio arrived at Covington with no ammunition and very poor weapons. “A few of the officers and a great many of the men refused to march and Co. K actually stacked their arms,” he reported. Only five companies of the regiment moved on to Cynthiana as a result. See O.R., op. cit., pg. 34

[5] Hapgood, op. cit. Colonel Asper reported that the regiment arrived at 4 a.m.

[6] Letter from Private Ephraim F. Jagger, Portage County Democrat (Ohio), June 22, 1864, pg. 2. After delivering the 171st Ohio, the train ran backwards for two miles where Morgan’s men captured it, knocked it off the rails and set it afire. A Confederate trooper placed obstructions on the rails that derailed the second train when it attempted to steam back north, injuring a number of the horses. The injured horses were left in the cars and burned while the healthy horses were appropriated by Morgan’s men. See “The Morgan Raid,” Pittsburgh Daily Commercial (Pennsylvania), June 14, 1864, pg. 1

[7] Hapgood, op. cit., also O.R., op. cit., pg. 56

[8] Reid, op. cit., pg. 701

[9] O.R., op. cit., pg. 57

[10] Jagger, op. cit.

[11] O.R. op. cit., pg. 63

[12] Jagger, op. cit.

[13] Jagger, opt. cit.

[14] Hapgood, op. cit.

[15] Jagger, op. cit.

[16] Reid, op. cit., pg. 701

[17] Hapgood, op. cit.

[18] Jagger, opt. cit.

[19] “In Cincinnati,” Gold Hill Daily News (Nevada), July 16, 1864, pg. 2

[20] Jagger, op. cit. It was reported that the Rebels burned the stacked arms rather than carry them along and, as General Morgan reported, his men had Enfield rifles and the Federals “old muskets,” likely .69 caliber as he could not use the ammunition.

[21] Hapgood, op. cit.

[22] Letter from Ephraim F. Jagger, Portage County Democrat (Ohio), June 29, 1864, pg. 2

[23] Reid, op. cit., pg. 702

[24] Hapgood, op. cit.

[25] O.R., op. cit., pg. 59

[26] Jagger, op. cit. June 29, 1864

[27] Hapgood, op. cit.

[28] This road today is Kentucky Highway 19.

[29] Hapgood, op. cit.

[30] Reid, op. cit., pg. 702

[31] Letter from F., Western Reserve Chronicle (Ohio), August 10, 1864, pg. 2

[32] Letter from George N. Hapgood, Western Reserve Chronicle (Ohio), August 3, 1864, pg. 2

Dan Masters holds a bachelor’s degree from the University of Toledo and has been actively engaged in Civil War research for more than twenty years. Dan lives in Perrysburg, Ohio with his wife and five children, while his oldest son is currently serving in the U.S. Air Force. His work has been featured in America’s Civil War, Maryland Historical Magazine, The Western Tennessee Historical Society Papers, and Northwest Ohio History. Dan is the author of six books about the Civil War, the latest being The Seneachie Letters: A Virginia Yankee in the 32nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry published by Columbian Arsenal Press. He also frequently posts articles to his blog: https://dan-masters-civil-war.blogspot.com/

Great article, growing up in Niles Oh I always came across stones marked 171st Oh in Union cemetery. Knew they were a 100 day unit but never thought about there service. Thanks for shining some light in this unit

I researched this also and have three chapters with new maps on the Second Battle of Cynthiana in my book “Kentucky Rebel Town: the Civil War Battles of Cynthiana and Harrison County” published by the University Press of Kentucky in 2016.

Bill’s book is excellent, and Dan’s article really fills in many details!

Really excellent article, Dan! Side note – Future president William McKinley’s cousin Joseph Osborne was killed in the fighting at Keller’s as part of the 171st. And for those who would like a tour of both battles of Cynthiana, including accessing the private lands where the fighting near Keller’s bridge took place, I know a guy…just sayin’.

My great grand uncle Thomas H. Baggett was reported mortally wounded at Warwickshire, Hamilton, Butler County, Ohio in 1864……Thomas had previously served with the 1st Tennessee Inf. (Turney’s Regt.) and now possibly serving with John Morgan’s Cavalry……he might have been wounded and captured by Union soldiers at Cynthiana,Ky. and that is all I know…….Any further information I can find on Thomas would be greatly appreciated…. Thank You, Charles Lockley