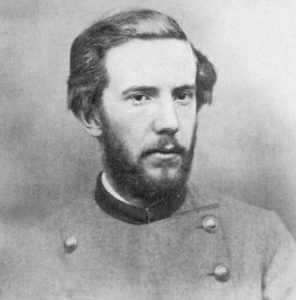

Conrad Wise Chapman and “The Life Insurance Brigade”

After Fort Donelson, Colonel John Eugene Smith of the 45th Illinois Infantry observed “The Boys were constantly wishing they could have a fight. You do not hear any such wishes now.” The soldier’s lament over the horrors of war is common enough in memoirs and letters. The sentiment of Smith’s men seems nearly universal. Yet there are exceptions. From Achilles to Ernst Jünger and Hans-Ulrich Rudel, there have always been men who relished combat. The Civil War had Conrad Wise Chapman.

Chapman grew up in Washington D.C. From 1848-1861, he lived in Rome, where he and his family created and sold paintings, mostly to American tourists. When war came, Chapman left to fight against his family’s wishes, egged on it seems by saber-rattling Southerners who lived in Rome.

Chapman never owned slaves, and slavery is almost never mentioned in this memoirs, save the occasional anecdote, one of which reflects negatively on slave-owners. While he had relatives and family friends in the South, Chapman was not motivated by a defense of wife and children that is so common in Confederate letters. Chapman was somewhat moved by a belief in the right of self-determination, which was often what Europeans admired about the Confederate cause. It appears he mostly did it because he wanted to defend the South and he had a particular hatred of the North. His vitriol against them in his letters and memoirs is among the most bitter I have ever encountered. His feelings for Virginia also ran deep. His first and middle name were derived from two prominent Virginia families that were friendly with his father.

Chapman took a ship to America and landed in New York City. He was detained but then released. Making his way to Nashville, he joined the 3rd Kentucky Infantry. He got into trouble with his commander, Lieutenant Colonel Albert P. Thompson. He admitted in his memoirs that if given a chance he would have killed Thompson. Even after Thompson praised him, Chapman still harbored a grudge, and all because Thompson understandably thought this weirdo from Rome might be a spy. Regardless, Chapman proved to be a model soldier. He fought at Shiloh and was wounded on April 7. He then saw action in the siege of Corinth and the battle of Baton Rouge. Although he liked serving with the Kentucky troops, he longed to be in Virginia. He got his wish when his namesake, Henry A. Wise, secured his transfer.

Wise was among the most powerful antebellum politicians. He had been an unofficial adviser to President John Tyler, served as governor of Virginia, and played a leading role in Virginia’s exit from the union. He was married three times, fought one duel and went from Democrat to Whig, and back to Democrat. His military career was no less tumultuous. He feuded with other commanders, notably his political rival John B. Floyd. Unfairly blamed for the loss of Roanoke Island, he then commanded a brigade in the Seven Days battles. When Robert E. Lee turned north to face John Pope, he left Wise in the Richmond defenses. Not only had Wise not proven himself, but Lee already had to contend with Virginia politicians William “Extra Billy” Smith and James Kemper. It is likely Wise and Kemper did not like each other, as they supported rival political factions in Virginia after the war.

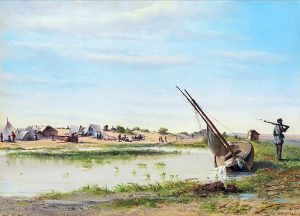

Much to his chagrin, Chapman found himself going from the hard work of fighting and marching to the steady grind of garrison duty. Chapman called Wise’s outfit “the life insurance Brigade” and said he would rather be a private in Lee’s army than a captain under Wise. He even tried to get a transfer to Lee’s command, but was turned down. Wise gathered friends and relatives, which led to accusations that he was protecting them. It was an unfair observation. Wise wanted to be at the front and tried to join James Longstreet’s corps when they were on the way to Chickamauga. Longstreet thought Wise’s brigade had grown weak from garrison work and would be a liability.

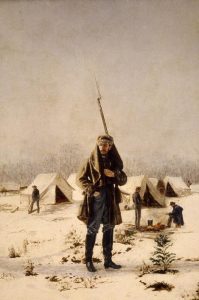

Chapman’s time was not in vain. He continued to sketch, which would lead to Picket Post, one of his finest works. He also took part in a raid on Williamsburg, which earned Chapman a commendation, promotion to sergeant, and two pistols. Chapman considered the raid the highlight of his career. Regardless, life in Wise’s brigade mostly consisted of assisting refugees and rounding up runaway slaves and unionists.

Wise’s brigade was eventually sent to Charleston, but by then the Union effort to take the city was winding down. P.G.T. Beauregard commissioned Chapman to sketch the city’s defenses, which led a series of paintings that are often considered among the best of the war. Upon hearing his mother was ill, Chapman got a position as secretary to Bishop P. N. Lynch, who was sent on a diplomatic mission to the Vatican. Chapman was recommended for an officer’s commission but nothing came of it.

When he arrived in Rome, Chapman found his mother had recovered, and he suspected it was a ruse to get him out of the Confederacy. He would have returned immediately, but he was too weak to make the voyage until 1865. When he reached Houston, Texas word of Lee’s surrender arrived. He fled with Kirby Smith to Mexico, where he lived for two years and did another round of impressive work. Chapman’s second home became Mexico, and he would later marry a Mexican woman.

After the war, Wise told Chapman he was lucky because “ten thousand events & scenes occurred since you parted from us.” Wise wrote “Kiss your dear Mother for drawing you away from suffering, wounds, humiliation & death. Had you got back to me how desolate you would have found me, Bereaved & alone but with honors…The old 2500 were reduced to 300 & showed good fight to the last.” From May 1864 to April 1865 the brigade was constantly under fire. Wise, whatever his faults and earlier mistakes, distinguished himself during this period, particularly in the defense of Petersburg on June 15, 1864.

Chapman bounced around Europe after he left Mexico in 1867. He started his wartime memoirs, although whether he stopped them or the rest were lost is unknown. They were only discovered in the 1970s. Chapman witnessed the siege of Paris during the Franco-Prussian War, which might have led to his mental breakdown. When he recovered in 1874 he finished Picket Post at his father’s request. It depicts Chapman on duty in the “Life Insurance Brigade,” a rare quiet self-portrait in a war where most paintings were dramatic renderings of battles and leaders. There were only moments of genius as he drifted between Europe, Mexico, and America. To many he was a minor talent, although his best work seemed to be at once classical, realistic, and impressionist.

Chapman never did become a great artist, or at least a consistent one. Yet, the soldier in him remained consistent. When the Spanish-American War began, Chapman, dropped everything, moved from Mexico to Virginia, and offered his services in defense of the state. Unable to make much of himself in Virginia, he moved again, but he did not blame Virginia. In a letter to his brother he said “I love the South for many reasons and one is that they would as likely look at a painting upside down as not. It is no country for artists, at every step one would meet some one to tell him to go to work–which does not mean paint.”

By the early 20th Century, some artists were taking note of Chapman’s Charleston paintings, but as a Confederate his work was generally shunned in New York City. He was mostly commissioned to paint scenes from Mexico. Yet, his grand ambition was a two part piece on “Stonewall” Jackson that featured his stand at First Bull Run and his wounding at Chancellorsville. He was commissioned to do both right after the war, but his patron’s finances collapsed. Facing death, Chapman tried once more, but after considering a move to Kentucky, he died in 1910. His last works were sketches of Bernard Bee, William Pender, and Jackson, three men who died fighting for the Confederacy. Chapman may have desired the same. He certainly liked the life of a soldier, and save for his Shiloh wound, his memoirs are distinctly lacking in the horror of war. He would later say that for good or bad, his character was formed in the Confederate army.

Chapman was lucky. He left the 3rd Kentucky Infantry before the meat-grinder of Stones River and Chickamauga. He was with “The Life Insurance Brigade” during a quiet lull between the horror of the Seven Days and the greater horror of Petersburg. Chapman longed for battle, even after the crucible of Shiloh and Baton Rouge, but we are fortunate that most of Chapman’s career was spent in relative quiet.

He also did the famous painting to the CSS Hunley. Surprised that wasn’t included.

https://moconfederacy.pastperfectonline.com/webobject/5D06A04C-AA99-4A19-9137-242514225690

I thought there was something familiar about his work. Good find! Thanks.

Sean, do you have a source on the John E. Smith quote? Thanks!

I ran into it in Smith’s recent book on Forts Henry and Donelson. I cannot recall where exactly off the top of my head though.

Thanks Sean!

Very educational thanks

I’m sorry to bother you .but I was wondering if you had a telephone for an appraiser, I have aoil painting on canvas 23×53 landscap signed Chapman thanks

I believe that the officer seated on the bay horse in the painting of Wise’s Brigade outside of Williamsburg is my Great Grandfather Col. John. T. Goode