Fences

I recently re-read Gettysburg: A Novel of the Civil War, the alternate history by Newt Gingrich and William R. Forstchen, and I wanted to share a couple lines from the first page that really struck me:

I recently re-read Gettysburg: A Novel of the Civil War, the alternate history by Newt Gingrich and William R. Forstchen, and I wanted to share a couple lines from the first page that really struck me:

“As [Lee] approached the knoll, the orchard gave way to pasture, the fence dividing the two fields broken down, the split rails so laboriously cut and laid in place gone, except for a few upright posts. He had spoken more than once about this, to not touch the property of these people, but after a hard day’s march such fences were easy to burn, and the pasture ahead was dotted with glowing fires. An entire winter of a farmer’s labor to fence this field gone now in a single night.”

First of all, the writer in me loves the fact that the authors used “fence” as a verb!

But more importantly, I thought this small episode struck at the heart of something that we, as Civil War buffs, all know but perhaps don’t fully appreciate. Any group of soldiers acted like locusts on a landscape, stripping away all sorts of resources. No orchard was safe, for instance; no chicken, untended, survived the day. Fences were particularly easy targets for soldiers in need of a campfire and too exhausted, after a day of marching or fighting, to forage for wood.

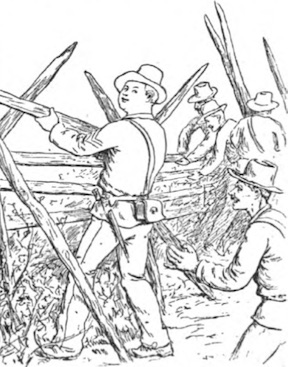

Soldiers were often prohibited from stripping fences down to the ground, permitted by orders to take only the top rail but to leave the rest. But as this sketch illustrates from Corporal Si Klegg and his “pard” (provided to me by my colleague Kevin Pawlak), the top-rail admonition was as hollow as it was well meaning:

Then there was a scramble for the fences. Recognizing the need of good fiel, an order from the general was filtered through the various headquarters that the men might take the top rails, only, from the fence enclosing the field. This order was literally interpreted and carried out, each man, successively, taking the “top rail” as he found it. The very speedy result was that the bottom rails became the “top,” and then there weren’t any. Almost in the twinkling of an eye the entire fence disappeared.

That brings us back to the Gingrich/Forstchen passage. The Confederate army has stripped away the fences. No surprise. But the authors give us some powerful insight into what that actually means: “An entire winter of a farmer’s labor…gone now.”

Imagine: working all winter to get a fence up–cutting the timber, splitting the rails and hauling and stacking them, assembling the fence–all gone. Poof.

Such is the power of fiction to get at truths that straight-up nonfiction can’t get at. And such is the value of material culture–in this case, fences–to keep us grounded and in contact with the physical world, now and from the past.

Great perspective born of long days of research and reading. Thanks.

Compared to what the Yankees took and destroyed in the South, a split rail fence being destroyed is trivial. I do understand it is fiction Chris but the first thing that came to mind was the wanton destruction and war waged on he civilian population, leaving many to die from starvation.

“Fences “ …. sometimes it’s the little grammar swag that hooks you or Unhooks you . I get this hook …

thanks Chris for bringing it to our attention , mine at least

If only the Federals took nothing more than the fences.

Tom

Another term for “alternate history ” is make-believe. Another term is “alternative facts”. Why read about something that NEVER happened as opposed to reading the facts, and the ACTUAL history.

This book is just another tome dedicated to the myth of the “Lost Cause”, what might have occurred if the North didn’t have more men, a better economy, a better Navy, more railroads, and the list goes on.

Let me give you the bottom line:

The South lost

Slavery was abolished

Loud voices always enter the room to remind you of the stain and prevent you from thinking like a human should. Stop enforcing binary thinking.

In his recent outstanding book, When Hell Came to Sharpsburg, author Steve Cowie includes in his analysis the myriad of economic losses and psychological damage caused by the destruction of fence rails by both sides. Thought-provoking.