Home Libraries: My Civil War Bookshelf – The Macmillan Wars of the United States

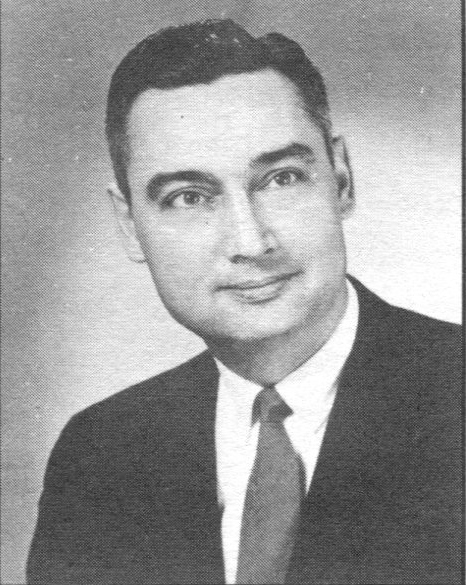

While conducting the research for my dissertation I spent more time in one archival collection than any other, a collection that does not appear in a single footnote and provided almost none of the information I had hoped it might for the project I am now undertaking. But even as my time at the Western History Collection at the University of Oklahoma wound down and stacks of archival boxes filled with accounts of life in the frontier army appeared at my desk, I found myself drawn every morning to the papers of Robert M. Utley, a historian who wrote many of the books that sparked my interest in the military history of the American West. Utley’s papers comprise 42 linear feet of journals, correspondence, calendars, and manuscript drafts, as well as research files. I had selfishly hoped to expedite some of my own research by looking at Utley’s already completed research and picking up a few tidbits that would fill out my chapters. What I found instead, in his voluminous correspondence, was a remarkable synthesis of the history of the American army in the nineteenth-century West.

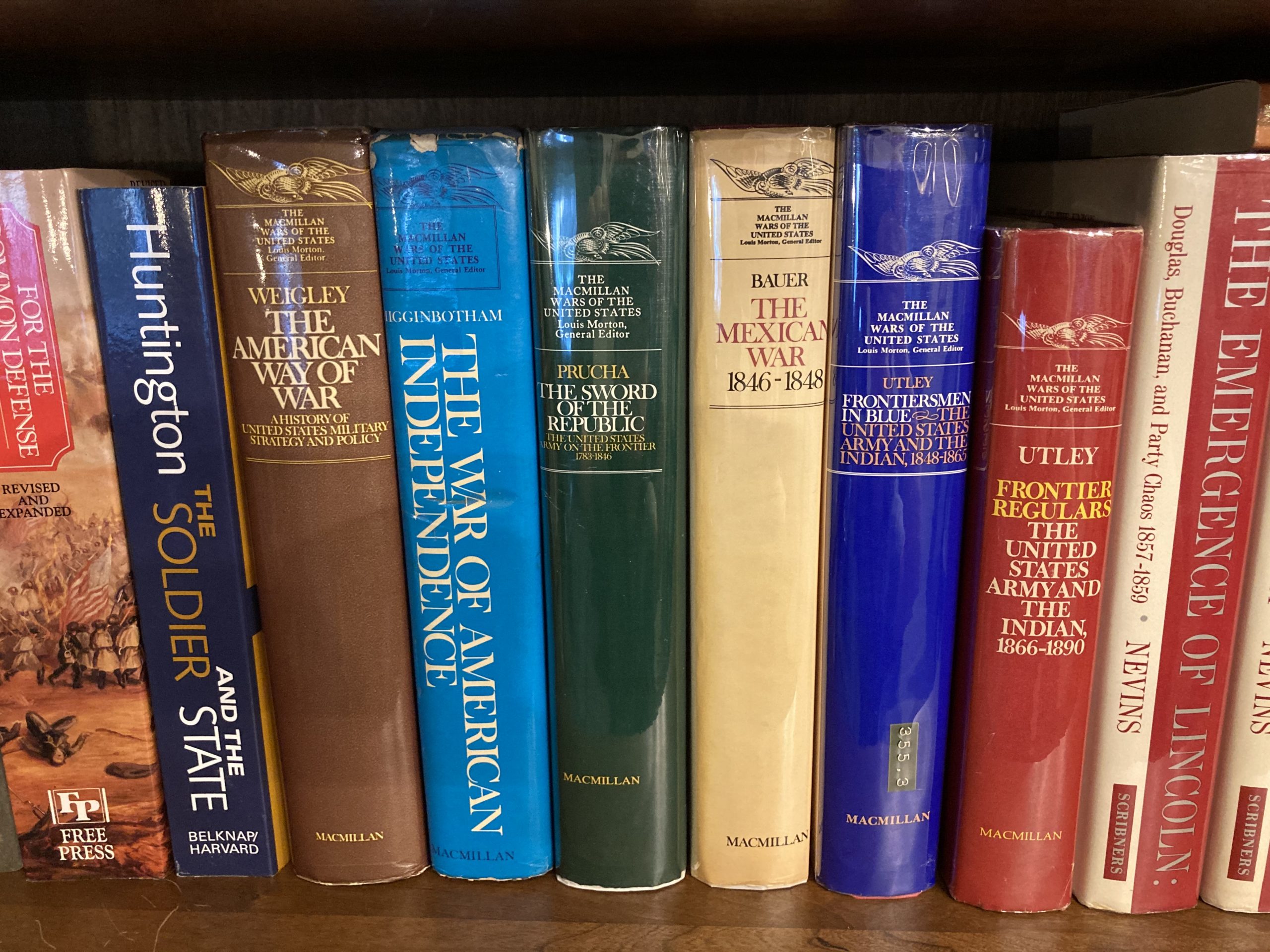

Utley contributed two books to a landmark series known as the Macmillan Wars of the United States, several volumes of which take pride of place in my library. Edited by Louis Morton, a historian of the Second World War who had served in that conflict and went on to teach history at Dartmouth, the series, as originally projected, would run to 20 volumes, covering every branch of the service and providing a standard treatment of every American war between 1607 and the Korean conflict.

Between 1967 and 1985, 14 volumes appeared in the series. The six missing volumes would have covered the War of 1812, The Civil War, The US Air Force, the Korean War, The European Theater in World War 2, and American Military Interventions (which would have been the only volume written by a woman, Annette Baker Fox, in the series). The volumes, in the order in which they appeared are listed below:

- Russell F. Weigley, History of the United States Army (1967)

- Francis Paul Prucha, The Sword of the Republic: The United States Army on the Frontier, 1783-1846 (1968)

- Robert M. Utley, Frontiersmen in Blue: The United States Army and the Indian, 1848-1865 (1968)

- Harvey A. DeWeered, President Wilson Fights His War: World War 1 and the American Intervention (1968)

- Clarence Clemens Clendenen, Blood on the Border: The United States Army and the Mexican Irregulars (1969)

- Don Higginbotham, The War of American Independence (1971)

- Russell F. Weigley, The American Way of War: A History of United States Military Strategy and Policy (1973)

- Robert M. Utley, Frontier Regulars: The United States Army and the Indian, 1866-1891 (1973)

- Douglas Edward Leach, Arms for Empire: A Military History of the British Colonies in North America, 1607-1763 (1973)

- K. Jack Bauer, The Mexican War, 1846-1848 (1974)

- Allan R. Millett, Semper Fidelis: The History of the United States Marine Corps (1980)

- David F. Trask, The War With Spain (1981)

- John K. Mahon, History of the Militia and the National Guard (1983)

- Ronald H. Spector, Eagle Against the Sun: The American War With Japan (1985)

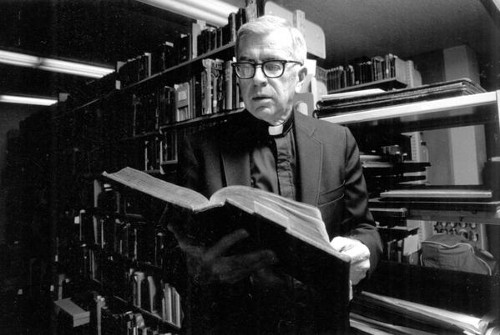

Few would argue that the conflict most notably absent from the “Wars of the United States” is the quintessential American war: the Civil War. As of 1967, the project was “in preparation” with historian Jay Luvaas slated to write the text. There is little doubt that Luvaas would have produced a sterling history of the war, as his other published works demonstrate his firm grasp of American military history and military thought. The project was never completed and Luvaas passed away in 2009. As there is no Civil War volume to write about for Emerging Civil War, I will focus instead on the three volumes that deal with the nation’s Indian Wars and the two authors who wrote them: Robert M. Utley and Fr. Francis Paul Prucha.

The editor of the Macmillan series, Louis Morton, desired that his authors “place military activities and institutions within a broad political, social, and economic context.”[1] Notably absent from Morton’s request was any exploration of the political contexts that surrounded the wars he wished his authors to write about. Morton asked Robert Utley to contribute the volume on the postbellum Indian wars—recognizing Utley’s knowledge of George Armstrong Custer and the frontier army as integral to the success of the series. Morton had already secured Father Francis Paul Prucha to write the earlier, companion volume on pre-Civil War Indian conflicts. Utley responded with delight tinged with concern, for he believed Morton, or the press, or someone along the way, had made a mistake in trying to divide the story of the nation’s Indian wars in half at the Civil War.

Utley proposed to Morton that he write a history that separated the nation’s Indian wars geographically, at the Mississippi River. This, Utley thought, would make more sense for both his volume and Prucha’s. “Conditions, problems, and responses,” Utley explained, “were entirely different east of the Mississippi than West of it.”[2] If Utley could not convince Morton of the logic of geographic division, he asked that he be allowed to start his study in the aftermath of Mexican-American War, so that he could treat the “Western story” as one of continuity, from the 1820s through to the 1890s. Prucha, writing to Morton and Utley, disagreed entirely with both of Utley’s suggestions. The Jesuit priest, who spent his academic career teaching and writing at Marquette University, said Utley’s point of view was typical of Western historians who exhibited a tendency to concentrate “on section, rather than the national picture.” Prucha proposed Utley begin at the Dakota War of 1862, because that is when he believed the army became committed “to a more or less desperate struggle to subdue a hostile enemy and confine the Indians on reservations.”[3] Thus, two of the greatest historians of the Indian wars found thus themselves at an impasse.

Utley ultimately accepted Morton’s brief to write a history of the army that began in 1866, leaving the wars of the antebellum East to Father Prucha. As Morton began receiving drafts, however, he realized had a second problem. Utley had tried to do too much in his military history. First, Utley had tried to slip in too much background materials on the events before 1866, encroaching with “imperialist designs” on Prucha’s volume. Second, Utley had filled his military history with long sections of administrative and institutional background that Morton believed to be “more material on non-military matters than would be necessary for most of your readers.” Morton wanted the political context for the Indian wars out of utley’s study. Morton reiterated to Utley that there was “little validity in the extended treatment of the army in the period between the Mexican War and the Civil War.” “Certainly,” Morton affirmed, “it did not differ so greatly from the pre-Mexican War army.”[4]

Utley could make little headway with his editor and in the end, he agreed to drop much of the administrative history he had prepared for the post-war volume. When he proposed a companion study that treated the years between the Mexican-American and Civil wars, he tried again to convince Morton of the necessity of discussing politics and administration, to no avail. Utley was perched on the cusp of what was then called “The New Military History” a set of methodologies that changed how historians approached military topics. Utley’s initial drafts would have been right at home among many of the early landmark works of “War and Society” that now define the field—representative works in Civil War history include Joseph Glatthaar’s masterful study of the USCT: Forged In Battle: The Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers and White Officers (1990) or Stephen V. Ash’s chronicle of Southern occupation: When the Yankees Came: Conflict and Chaos in the Occupied South (1995). They just happened to come two decades too soon for the field to welcome their interventions as military, rather than political history.

Utley’s frustration with the limits that the methodologies of military history placed on his ability to portray the full history of the army in the nineteenth century struck me in particular, especially as I contemplate writing a manuscript that discusses, in great detail, all of the things Utley’s editor thought did not belong in the volumes that still represent two of the standard texts on the subject. Perhaps I should have taken the correspondence as a warning, but instead, I persisted in my own obstinate fashion.

What I ultimately took away from Utley’s vast papers is that historians are small figures who dot an overwhelming landscape of evidence, opinions, and methods that bring all of us to different conclusions and spark debates that have no real winners, but at their best generate conversation and foster understanding. The Macmillan Wars of the United States represent a watershed in thinking about American military history, and, even better for readers more than five decades on from the first volume to appear: they hold up as works of history that treat extraordinarily complex events with keen insight and clarity.

—————————————————————————-

[1] Louis Morton, “Wars and Military Institutions of the United States,” Robert M. Utley Papers, Box 9, Folder 1, Western History Collection, University of Oklahoma, Norman. Hereafter WHC.

[2] Utley to Morton, July 2, 1963, Robert M. Utley Papers, Box 9, Folder 1, WHC.

[3] Francis Paul Prucha to Lou Morton, June 20, 1863, Robert M. Utley Papers, Box 9, Folder 1, WHC.

[4] Lou Morton to Robert Utley, September 19, 1963, Robert M. Utley Papers, Box 9, Folder 1.

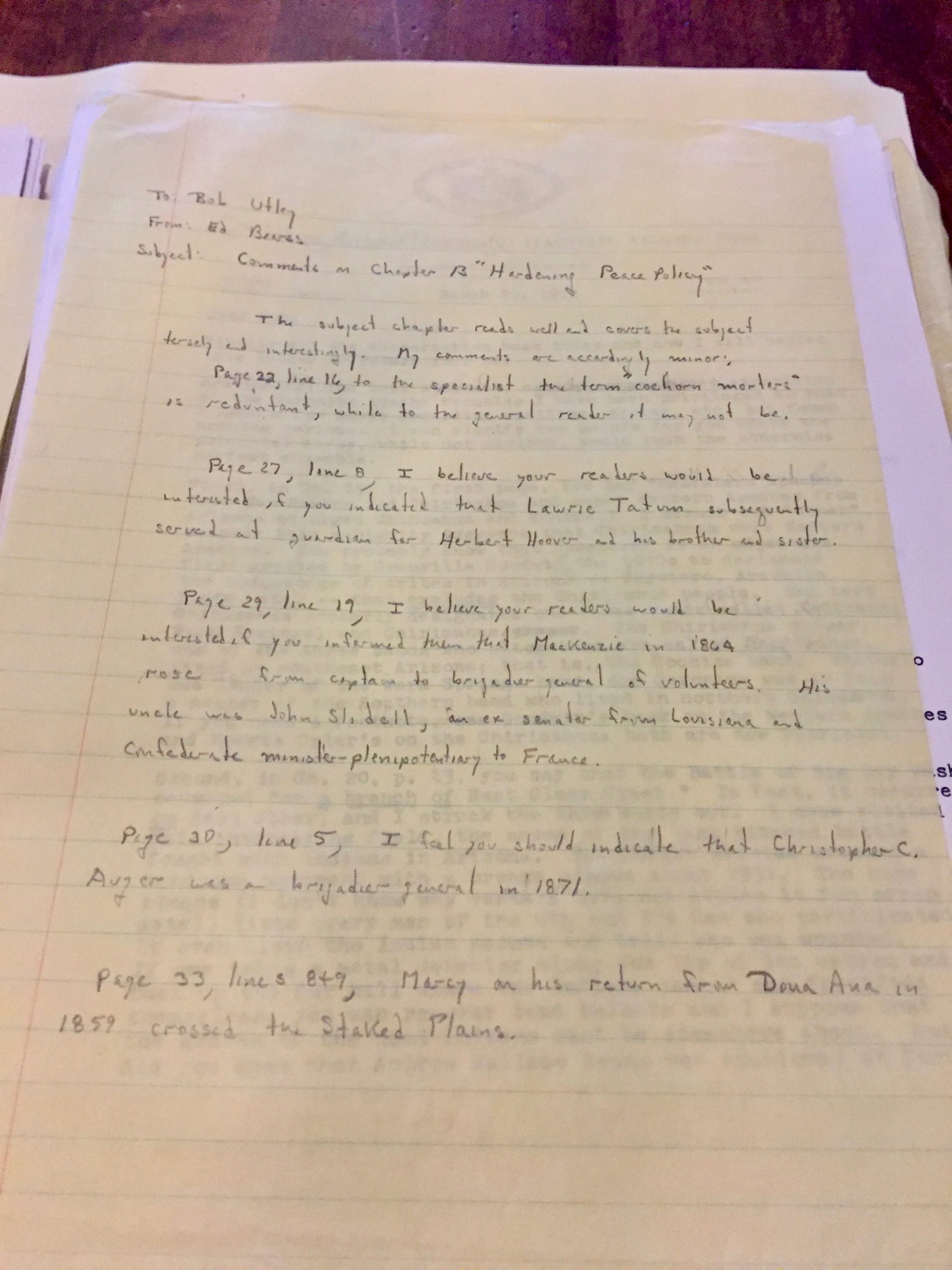

Wonderful and insightful article, Cecily. More please. It was also fun to read Ed Bearss’ handwritten notes. What a walking history encyclopedia that man was. Thanks for sharing.

Interesting — I have the “enlarged edition” of Weigley’s “History of the United States Army,” published by the Indiana University Press, and I can find no mention of “The Macmillan Wars of the United States” apart from fine print on the copyright page stating “First edition published by Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.”

I also have Spector’s “Eagle Against the Sun,” purchased at a used book sale minus dust jacket, and mention of “Macmillan Wars” was not all all prominent — unless that’s something that would have appeared on the jacket.

I had two of the series as college history course texts — Eagle against the Sun and Revolutionary War. I don’t remember what book the course used for WWII in Europe