Return to Burgess Mill

“I am now outside the main rebel line, moving southwesterly over the old Boydton Plank Road, which has ceased to have any vestige of a plank crossing it as long ago when the war was on. There is now nothing in the landscape I ride suggestive of war’s alarums, though armed men in legions tramped up and down this thoroughfare in 1864 and ’65.”

John Billings was visiting the old Petersburg battlefields where the 10th Massachusetts Light Artillery had fought. In 1881 he had written a history of the battery and followed that up with Hard Tack and Coffee, a much-acclaimed insight to the life of a common Civil War soldier. Additional material had come available to enhance the previously published The History of the Tenth Massachusetts Battery of Light Artillery and Billings traveled his former battlefields once more, lugging around a camera to capture the scene. Afterward he wrote several letters to the National Tribune chronicling the experience. By comparing this correspondence with the published unit history, we can match up one of the photographs Billings took during his visit—a rare research blessing, particularly for Petersburg’s western front.

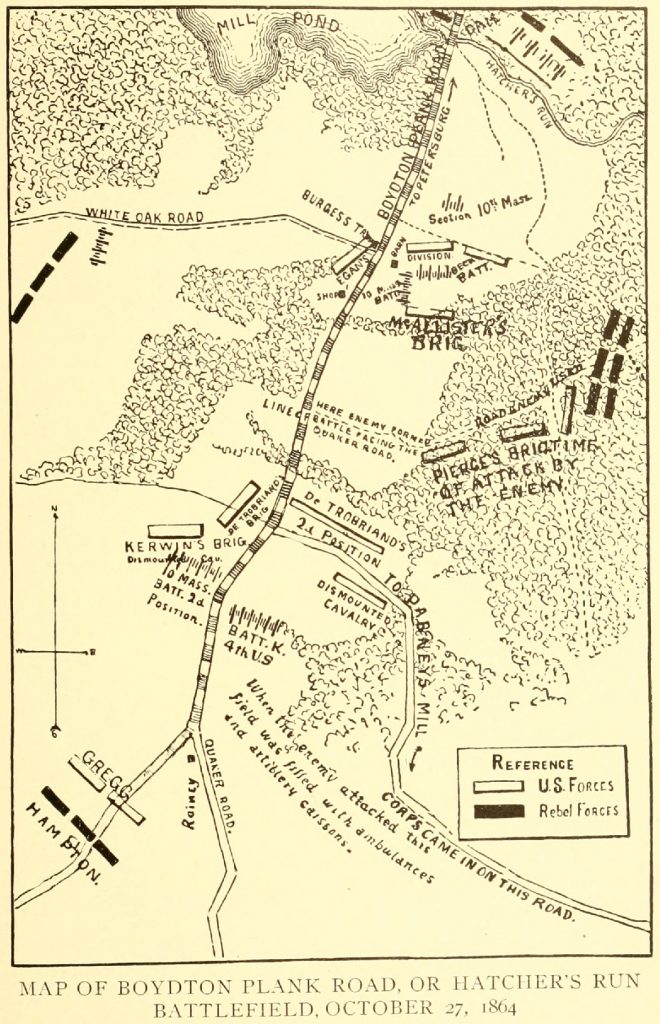

Ulysses S. Grant launched his Sixth Offensive at Petersburg on October 27, 1864. The 10th Massachusetts Light Artillery accompanied the Second Corps expedition to cut the Boydton Plank Road. The Confederates were primarily relying upon the route at that time due to their loss of the Petersburg (& Weldon) Railroad in August. The Union Fifth and Ninth Corps also stretched west to assist Winfield Hancock’s men, but failed to maintain their connection. This allowed William Mahone to slip three brigades across Hatcher’s Run and launch a surprise attack against the Second Corps as it consolidated around the Burgess property.

The 10th Massachusetts had been engaging Confederate batteries to the west along White Oak Road and to the north across Hatcher’s Run, in anticipation of a general advance up the plank road. “We of the other sections had now ceased firing, and were watching the charging party with eager interest,” Billings recalled in his history of the battery.

“They press on quite steadily without serious opposition, and have almost reached the bridge, when a sharp musketry fire breaks out in the woods to our left rear, and the line is immediately faced about. We are flanked and cut off! is our first thought. What else can it mean? The stoutest heart trembles at the possibilities of the immediate future. We can stand a hot fire from the front when allowed to give in return, and feel as comfortable as the situation warrants; but to be so sharply and unexpectedly assailed in the rear, is weakening to the strongest nerves.”

Billings’s section directed their fire at the new threat. “At once we send Hotchkiss percussion shells crashing into the woods at point-blank range, for the enemy are less than three hundred yards distant.” The sudden appearance of Mahone’s infantry on the Second Corps’ flank stalled Hancock’s planned advance northward. This allowed the Confederate artillery to reconcentrate their fire onto the Union batteries. The 10th Massachusetts withstood the barrage and stayed on the field long enough to expend all their ammunition.[1]

Mahone’s attack eventually lost its momentum but the Union offensive had been blunted. Despite temporary capture of their primary objective at the plank road, the Second Corps slunk back to the safety of its main lines—a recurrence of their prior performance at Jerusalem Plank Road in June and Reams Station in August.

Billings recrossed the landscape two and a half decades later with the benefit of an escort. William Burgess had moved his family from western New York to the Petersburg region in the 1850s. They opened a tavern at the junction of Boydton Plank Road and White Oak Road and operated a saw and grist mill on Hatcher’s Run. William’s son Clark stayed in New York during the Civil War but returned to Dinwiddie County afterward to take over the damaged property. Billings wrote how Clark helped him navigate the property in one of his letters to the National Tribune:

“He has preserved many of the incidents related to him by his father on his return home at the end of the war. Among others, he relates that the members of Gen. [Thomas W.] Egan’s Division, which lay across the road at this point, lost so many dippers, canteens, pots and kettles in his well during their stay there that afternoon as to entirely choke it up and compel the old gentleman [William Burgess] to go to the Run for water.

“The old house, also, was used as a hospital, and when the Surgeons amputated a leg or an arm they threw it out of the window, where it was seized upon and carried off by the hogs which were roaming about the place—not a pleasant reminiscences.”[2]

Clark’s cousin Daniel served as a Union surgeon and found himself on his family property during the October battle. “I was under severe fire at this occurrence, and candidly admit that I did not relish the reception of my comrades and myself upon my visit to my own uncle’s home,” Daniel afterward recalled. “To be sure, neither he nor his family were then occupying it, for the house was in the direct line of fire between the two armies, and although occupied as a temporary hospital for a time, had become riddle by gun fire and the family had moved temporarily to a quieter and less dangerous residence.” While he dressed injured soldiers, Daniel himself was wounded in the left arm by a shell fragment.[3]

The Burgess’s land additionally witnessed combat and largescale troop movements during the Beefsteak Raid (September 1864), Hatcher’s Run (February 1865), Lewis Farm (March 29, 1865), White Oak Road (March 31, 1865), and Petersburg Breakthrough (April 2, 1865). Clark guided Billings across the property and pointed out the notable remaining features, including the outlines of a Confederate fort built after the battle which the family had since leveled to make room for their kitchen garden.

“A fine new and commodious barn stands close to the spot occupied by the little old rickety affair in and behind which wounded and tired men lay after the first attack,” Billings informed the National Tribune. “After using my kodak to carry away a few views of the spot where Cannoneer Atkinson, of my own gun, was killed, and Lieuts. Granger and Smith, our only officers present, mortally wounded, I enter the buggy and drive still farther on to the point where the Second Corps came on to the field.”[4]

Billings later published one of these photographs in 1909 battery history. Thus, because he diligently conducted his own field research, historians have a tangible link to the battlefield on which the Massachusetts artilleryman fought.

In addition to the sources referenced below, those interested in Grant’s Sixth Petersburg Offensive should consult Hampton Newsome’s Richmond Must Fall: The Richmond-Petersburg Campaign, October 1864 (Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press, 2013).

[1] John D. Billings, The History of the Tenth Massachusetts Battery of Light Artillery in the War of the Rebellion, 1862-1865 (Boston: The Tenth Massachusetts Battery Association, 1909), 358.

[2] “In the Trenches,” National Tribune, January 21, 1892.

[3] Daniel M. Burgess, Personal and Professional Recollections (New York: Printed for Private Distribution, 1911), 52.

[4] “In the Trenches,” National Tribune, January 21, 1892.

Great piece. The Battle of Burgess Mill is an interesting battle as more engagements would take place the following year in 1865. However, did the II Corps manage to hold any new position or did the II Corps fall all the way back to their initial position? I have always been a bit confused by this.

Nothing gained on the opposite bank of Hatcher’s Run. The February fighting would produce the foothold that allowed the strategy for the final March-April offensive.

Great article. I must say I’m very, very impressed with Billings facial hair.

Clark was my great great grandfather. I have pictures

Visit my wall to see pictures from 1897

I would love to see pics. I also believe we could be related. My husband’s third Great grandfather is rumored to be a Texas Ranger, but finding facts are tough. Do you think Burgess Mills lands is in your family tree?

Daniel Maynard Burgess was the sawbones on site

Great article, wonderful details. Billings book gives a rare detailed account of the Hatcher’s Run battle in February 1865, where sections of the 10th Mass Artillery made a substantial contribution to the fighting on Feb 5th and helped to protect the II Corps during the Confederate attacks.

My great grandfather was with the 12th New Jersey and captured at “Stone Mill Creek”. I assume it was in the area but I cannot locate it on period maps. Do you know where it is located? It was on my great grandfather’s service record as the site of his capture. Thank you.

My gr gr grandfather was captured Burgess Mill Oct 27. Edwin Henry Young.41st Va Mahones Sent to point lookout and exchanged at Aiken landing March 15. His home was at the corner of Youngs road and Boydton plank road 7 miles from the battle. He married Helen Armstrong of Armstrongs mill Hatchers run in 1874. She was 11 years old during the battle. He was 18. Armstrongs had four farms around the mill. where her father was killed by rebels in 1863 for hiding southern deserters his brothers and friends underground. Maybe Edwin Henry Young also. All were from company B 41st Va. .The Armstrongs were from Otsego New York and came to Va in 1853. and Youngs family’s from Virginia. 1730s still going strong. Thanks