German Prisoners of War in Gettysburg

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Jon Tracey

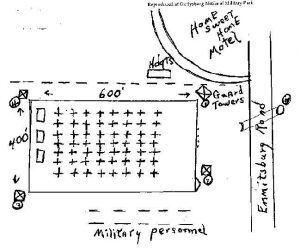

A gathering of prisoners of war at Gettysburg doesn’t sound like a surprising topic at first glance. However, the soldiers in this particular camp were not Union or Confederate, they were Germans captured during the Second World War! During the Fall of 1942, the War Department agreed to house German prisoners of war on American soil, leaving the government with the question of where exactly to house them. One such camp was within Gettysburg National Military Park; its remote location made the site attractive for use as a prisoner camp.[1] Additionally, existing facilities in the form of an old Civilian Conservation Corps camp and nearby labor shortages caused by the war made the selection more attractive. Located along the west side of the Emmitsburg Road, south of the Home Sweet Home Motel and Long Lane, the camp was built by fifty German prisoners sent from Fort Meade, Maryland.[2] The camp sat among the fields that witnessed Pickett’s Charge.

Arriving German prisoners quickly found themselves put to work, as both then and now Adams County had no lack of agricultural industry. Any farmer, packing company, or orchard owner could apply to the local employment service, which coordinated contracts between local farmers and the military. The initial group of prisoners found themselves assigned to “fourteen canneries, both fruit and vegetable; three orchards, seventeen farms, one stone quarry, and one fertilizer and hide plant.”[3] The prisoners would be guarded at all times and transported to various locations in Littlestown, Biglerville, Hanover, Chambersburg, Middletown, and Emmitsburg. The employers paid $1.00 an hour, with the majority going to the government while 10 cents would be credited to the prisoners in the form of coupons that could be used at the post exchange, as it was worried that giving prisoners actual cash would fund escape attempts.[4] After the vegetable season, the prisoners shifted to cherry harvesting and moved on to apple harvesting in the fall of 1944. Both these assignments were rather popular, as prisoners ate while they worked, and often smuggled pockets filled with fruit back to camp. When harvest season came to a close, many prisoners were moved elsewhere, and the number of prisoners diminished. Down from 400 to 200, these remaining Germans were moved from the tent camp to the old Civilian Conservation Corps barracks for the winter and were given unpopular tasks such as cutting pulpwood and clearing underbrush.[5]

German prisoners were generally content within the boundaries of the camp at Gettysburg. In fact, they were sometimes seen as treated too well, leading to backlash from American civilians who commented that prisoners were “well fed and living the good life while brave Americans were ‘neglected and starving,’ [and those] feelings were exacerbated as Nazi atrocities became known at the war’s end.”[6] One prisoner even returned to visit the plant he worked at during the war both to visit old coworkers and get a better look at the design, as he worked in construction in Germany and wished to emulate the design.[7] Another prisoner, Carl Brantz, remembered his experience fondly and returned in 2001. Assigned to the woodcutting team, he also served as an interpreter, and said that even if he could, he “would give back not one little thing.”[8] Germans found the United States far different than Nazi propaganda had envisioned it. Some prisoners said that they “had purposefully surrendered to the Americans to get a chance to see America and to be safe from the battlefield,” and many claimed to be conscripts who had never fired a shot.[9] One had even surrendered and proceeded to save the lives of several wounded Americans immediately after.[10]

Although interaction between townspeople and prisoners was forbidden, that was a rule that generally fell by the wayside. Prisoners would often talk to the Americans who worked beside them, as “most of them could speak some English as well as carry on a conversation [and] would like to talk to people to gain knowledge of the area.”[11] Eventually Captain Thomas, one of the American officers, became tired of locals gawking at the prisoners, and gave an interview mentioning that “the nuisance of women loitering about the camp had let up considerably but that an alert lookout is being maintained to prevent a recurrence of the habit of many women driving to and remaining near the camp site.”[12] The German prisoners were seen less as a threat or as an enemy, but rather as a generally harmless curiosity. Even managers who had hired the prisoners looked upon them in a positive light. Another farmer mentioned how he enjoyed giving the Germans cigarettes and allowing prisoners to eat the fruit they harvested; it made them get more work done![13]

Though there was little fear of escape, a few notable events made the camp the center of more dramatic events. On July 5, 1944, two prisoners, Thomas Kostaniak and Axel Ostermaier, used the drainage pipe beneath the Emmitsburg Road to escape towards the High Water Mark.[14] They were captured on June 11, 1944 in a farmhouse near York, and were taken into custody without resistance, having been distracted until police arrived by a farmer who was feeding them. They were described in good condition, having lived off of local orchards, with one merely “badly in need of a shave.”[15] It was remarkable that they had evaded capture for so long, as they had no money, did not speak English, and were wearing the denim uniforms and raincoat that had “P.W.” stenciled on them.[16]

A smaller escape was also detailed in the local paper. Two men in PW stenciled clothes were found on the curb in front of The Plaza restaurant, now the location of the popular Blue and Gray Bar & Grill. Officers in town thought they looked familiar and picked them up to return them to the camp.[17]

The final escape occurred in January of 1946. The war was technically over, but the repatriation of POWs was being delayed until their labor was no longer needed. Hans H. Harloff and Bernard Wagner had escaped the camp by slipping under the barbed wire at a corner of the camp at 10:50 p.m. January 3. However, when asked about their reason to escape, they answered simply that they “liked America, wanted to see more of it and hoped to reach a large city and stay in this country rather than return to Germany.”[18] This escape led to a great deal of local drama, as three locals were arrested for helping the prisoners. Byron Cease, his wife, and his daughter Pearl were all arrested, as they had given Harloff and Wagner “food, clothing and assistance” as well as the location of an abandoned home.[19] Apparently, Pearl had met one of the prisoners while working at the canning factory, and had smuggled notes back and forth. After escaping, the Germans anticipated they would find help there, and had made their way there. Although the family was arrested, the local judge decided to release them, as the war was over and “a period of imprisonment would serve no good purpose in view of the good reputation bourne by the family in Adams County.”[20]

Ultimately, the POW Camp at Gettysburg was a successful operation. The camp provided much needed labor for the Gettysburg area, and raised thousands of dollars for the federal government, essentially paying for itself. Whether it was hundreds of prisoners harvesting in the summer or a lesser number clearing brush in the National Military Park in the winter, necessary labor was carried out at low prices. The German prisoners remembered their captivity fondly, considering captivity at the hands of Americans as far preferable to fighting. They lived in relatively good conditions, received mail from home, enjoyed leisure activities, took advantage of opportunities for education, and earned wages. The area was strange but enticing, and the local people made fascinating co-workers to the Germans. The local area was generally accepting of the arrival of what they considered a curiosity as they were enemies who were simultaneously likeable and familiar. Despite short-lived escapes and tensions caused by those events, many of the stories about the camp show that it was a place where Germans acclimated to American society as well as a place where Americans cooperated with their enemy.

Jon Tracey holds a BA in History from Gettysburg College and is currently pursuing a MA in Public History and Certificate in Cultural Resource Management from West Virginia University. He has worked as a park ranger for three seasons at Gettysburg National Military Park, and previously worked at Appomattox Court House National Historic Park, Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park, and Eisenhower National Historic Park. His primary focuses are historical memory, veterans of the war, and Camp Letterman.

[1] Jennifer Murray, On A Great Battlefield: The Making, Management, and Memory of Gettysburg National Military Park, 1933-2013 (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2014), 56.

[2] Sara Fuss, “Gettysburg’s WWII Prisoner of War Camp,” Emmitsburg Area Historical Society, http://www.emmitsburg.net/archive_list/articles/history/gb/war/ww2_prisoner_camp.htm

[3] “The Prisoner of War Camps Located in Or Near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, During World War II 1944-1946,” Adams County Historical Society.

[4] Ibid,.

[5] Ibid,.

[6] Elizabeth Atkins, “The Prisoners Are Not Hard to Handle:” Cultural Views of German Prisoners of War and Their Captors in Camp Sharpe, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Thesis, 8.

[7] Marcus Ritter, “Plant Manager at Knouse Foods,” interview by Adams County Historical Society.

[8] Ed Reiner, “German POW Pays Nostalgic Visit,” Gettysburg Times, July 16, 2001.

[9] John and Stella Schwartz, “Memories of the German Prisoners of War Working at the B.F. Shriver Canning Company,” interview by Adams County Historical Society.

[10] Robert Frederick, “German Prisoner of War,” First Special Service Force, December 9, 1943, Library Gettysburg National Military Park.

[11] Ibid,.

[12] “More Prisoners of War Expected Here this Month,” Gettysburg Compiler, August 12, 1944.

[13] Russel Weaver interview by Adams County Historical Society.

[14] Major Laurence C. Thomas, “Location of the Prisoner of War Camp on the Gettysburg Battlefield during World War II 1944-1945,” Library Gettysburg National Military Park.

[15] “Nazi Prisoners are Captured in York County,” Gettysburg Compiler, July 15, 1944.

[16] “Find No Trace of Prisoners Who Fled Camp,” Gettysburg Compiler, July 8, 1944.

[17] “Escaped POW Surrenders in Brooklyn,” The Gettysburg Compiler, Oct 27, 1945.

[18] “Escaped PWs Recaptured; ‘Like America’,” Gettysburg Times, Jan 9, 1946, Library Gettysburg National Military Park.

[19] “Three Countians Are Arrested for Helping Escaped German Prisoners,” Gettysburg Compiler, March 9, 1946.

[20] “Byron Cease, Wife and Daughter Given Suspended Terms in P.O.W. Escape Case,” The Gettysburg Compiler, May 11, 1946.

Great article, and a side of Gettysburg I had no idea about. I’m guessing these POWs were primarily POWs from North Africa?

Chris,

Yep, these POWs were primarily captured during the North African campaign. Interestingly, the US actually divided up prisoners not only by rank but also by political affiliation – from my understanding Gettysburg was supposed to be one of the camps holding prisoners with fewer ties to the Nazi party. It was really interesting to see how the Germans both blended in as well as stood out from their Pennsylvanian neighbors.

Such an interesting article. Thanks!

Thanks!

A totally unexpected and refreshing subject. I believe Mobile was also a holding place for German POWs, but I don’t know all the details. Thank you for sharing!

Thanks for the kind words! The government used Gettysburg for a lot of unusual things in the 1900s. It must have been strange to be a POW clearing brush from the battlefield and sleeping under the view of monuments. I’d be curious to hear about Mobile!

I’m sure the Germans received a decent education about the battlefield that way.

I’ll have to inquire more about Mobile. The only thing I’ve heard mention of was that the Germans were given old uniforms to wear, and I’m not sure if that was of the Union or Confederate variety. I also don’t know if that’s 100% true.

We can only hope a guard or Park Ranger had the time to explain it to them!

Interesting! I think I’ve heard that in reference to some story before. Sounds perhaps unlikely, but intriguing nevertheless.

The father of a boyhood friend of mine was captured in North Africa in 1943 and brought here to San Diego, to a similar situation as described in your article. He spent the remainder of the war working in warehouses, unloading trucks etc.. After being returned to East Germany after the war, he escaped to the West in the dead of winter with his wife and first child and eventually was granted asylum in the US. He elected to be resettled in San Diego because “The people were nice and I loved the weather.”

A testament to the good people of San Diego.

Indeed! I did not come across stories of any of these POWs returning to make a home in Adams County, but it certainly seems that they enjoyed the area and the residents. I would not be surprised at all to hear that some of them immigrated postwar. “The people were nice and I loved the weather,” a wonderful compliment.

As we know, Bermuda was a staging base during the Civil War for blockade runners preparing for the last leg of their run of contraband goods to the Confederate seacoast. During the Anglo-South African Boer War of 1899- 1902 the British Crown Colony of Bermuda was used as POW camp, housing thousands of captured Boer fighters and their families. The point: reuse of strategic locations and utilization of expanses of open fields (including Gettysburg) for camps, supply dumps and air fields during times of national emergency is in keeping with the natural order of things. Nothing unusual, except that the episodes of impromptu use are seemingly so readily forgotten.

Certainly. Gettysburg saw government use as many things: a mobilization camp in the 1910s, hosted Camp Colt the Army Tank Corps camp, hosted Civilian Conservation Corps workers, hosted Camp Sharpe the intelligence training camp, and this POW Camp to name just a few.

Certainly the appeal of a large amount of space owned by the government proved appealing for many different reasons at different times. It seemed so natural a decision then, but can seem strange in the view of modern individuals who are more preservation-minded.

What an interesting story, especially the escapes!

The escapes are humorous in just how light-hearted the stories appear in retrospect!

However, the camp had some darker evens as well. On November 8th, 1944, 38-year-old prisoner Private Georg Hartig was found hanged from the rafters at the Adams Apple Products Corporation plant in Aspers. On September 1st, 1945, camp guard and Pacific theatre combat veteran PFC Joseph F. Ward died in a guard tower when his carbine fired upward through his skull and the tower roof. It was ruled a negligent discharge, but it could have possibly been suicide.

There appears to be a DATE ERROR…. TYPO?… in the following Quoted section

Of the article … you can’t go Backwards In Time..ie escape on July 5, 1944 & re captured on JUNE 11, 1944…could it have been escape on July 5, 1944 and recaptured on JULY 11, 1944?

Or escaped on June 5, 1944 & recaptured on June 11, 1944?

“Though there was little fear of escape, a few notable events made the camp the center of more dramatic events. On July 5, 1944, two prisoners, Thomas Kostaniak and Axel Ostermaier, used the drainage pipe beneath the Emmitsburg Road to escape towards the High Water Mark.[14] They were captured on June 11, 1944 in a farmhouse near York”

James,

Thanks for catching that. They escaped and were re-captured in July. My apologies.

Out I curiosity I pulled up foot notes 15 thru 19 which took me to interesting articles re the escaped prisoners when I copied foot note Title INDIVIDUALLY into GOOGLE

I’m from Greencastle and my dad owned and operated The Greencastle Packing Co. As a teen ager I worked at the packing company and clearly remember the German prisoners coming each day under guard to help. It’s true their labor was sorely needed as most of the young men, a few years older than me, were in the service. I also remember feeling those prisoners were very lucky to be out of the war, and our men, some of them my friends, were in combat and shot. This was upsetting to say the least.