The Lost Cause of John McCausland

Emerging Civil War welcomes guest author Jeffrey Webb…

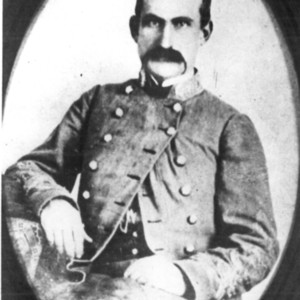

The Confederate Army’s John McCausland waited on the outskirts of Appomattox on Sunday morning, April 9, 1865. At that point, the brigadier general’s command, in his own words, “was reduced to a mere skeleton of 200 men.” When news reached him of Lee’s surrender, he knew it was all over. McCausland turned to the man next to him and said, “Let’s get out of here.”[1]

From Appomattox, McCausland and his men fled west, making their way to Lynchburg, Virginia. From there, the troops went their separate ways. McCausland ended up in Canada and then Europe before returning back across the Atlantic to Mexico. There, he witnessed firsthand the reign of the emperor Maximilian I. McCausland wasn’t the only ex-Confederate to relocate here after the war. The emperor established a colony specifically for ex-Confederates known as Carlota. However, the general’s time in Mexico, like Maximillian’s reign, was short-lived. It wasn’t long before the people of Mexico overthrew the empire, and in 1867 McCausland returned to the United States.[2]

By this point, for many Americans, the war was over. For McCausland, the war would never be over. John McCausland wasn’t built for surrendering. In 1864, at Cloyd’s Mountain in Pulaski County, Virginia, McCausland’s commanding officer was wounded in a battle that saw Confederate forces outnumbered three-to-one. McCausland assumed full command and executed an impressive retreat rather than surrender.[3]

It was to the new state of West Virginia, with a staunch pro-Union citizenry, that McCausland returned in 1867. He settled in an area that had once been, before the war, his family’s home.

McCausland, at thirty-one years old, purchased acres of swampland in Mason County, West Virginia, near Point Pleasant. With the same uncompromising spirit he demonstrated as a soldier, McCausland worked these swamps into one of the most profitable farms in the valley. “He stopped fighting when the war ended, and went to farming,” stated an 1895 article in The Point Pleasant Weekly Register.[4]

Still, despite his new life as a farmer, McCausland was known as “the general,” even by his children. In the early years after the war, McCausland regularly traveled to White Sulphur Springs in West Virginia, where he met with other generals like Robert E. Lee, P. G. T. Beauregard, and John B. Hood, trading war stories as well as laments. His home–a huge stone structure described as fortress-like–was decorated with memorabilia from the war: a sword gifted to him by the city of Lynchburg, volumes of The War of the Rebellion, and his commission as brigadier general framed and signed by Jefferson Davis.[5] To his neighbors and the press, McCausland was an embittered recluse holding fast to the glory days of the South.[6]

Few have written more about McCausland’s post-war years than Garnett Laidlaw Eskew. Eskew started his career as a reporter in nearby Charleston, West Virginia. He became one of the few reporters granted access to McCausland, profiling the aging general in such publications as the New York Times and American Legion Magazine.

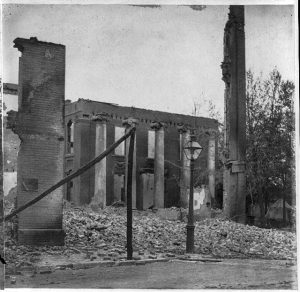

In the latter, Eskew detailed a 1925 Thanksgiving dinner with McCausland. During this dinner, the general related, for the first time to Eskew, his version of events leading to the destruction of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. As a general, McCausland ordered the town’s torching, the infamous act forever a stain on his reputation. “I am the most maligned man in the country,” McCausland told Eskew, referring to his vilification in the North. “The order [to burn Chambersburg] was distasteful to me. Still, as a soldier I had to obey orders.” McCausland showed Eskew an 1867 letter written by Ulysses Grant on McCausland’s behalf, the letter stating that officers and soldiers following orders should be exempted “from trial or punishment for all acts of war.”[7] At that point, the letter was fifty-eight years old. Did McCausland show it to Eskew that day for the reporter’s benefit or his own, a balm for a guilty conscience?

McCausland died in 1927 at 91 years old. Only one other Confederate general, Felix Robertson, survived him. Robertson, however, retired to Texas after the war, far-removed from the blood-stained fields of Appalachia where McCausland spent his final days reflecting on what could have been.

Eight years after his death, in 1935, John McCausland’s oldest son, Sam, was arrested and convicted for the murder of Chester Howard West. West was a war hero, a Medal of Honor recipient for his daring actions in World War I. He’d come to work on the McCausland farm and in a disagreement Sam McCausland shot him with a rifle.[8] The rifle had belonged to Sam’s father. It was a remnant from the general’s war. Perhaps the gunshot that killed West was one last rebel yell echoing through the West Virginia hills.

Jeffrey Webb is a teacher and writer from West Virginia. He holds an MFA in creative writing from West Virginia Wesleyan. He has contributed fiction and nonfiction to a variety of publications, including the Appalachian History, West Virginia Encyclopedia, and Teaching Tolerance.

[1] Garnett Laidlaw Eskew, “Last of Lee’s Old Guard Tells of the Forlorn Hope,” in New York Times, September 16, 1923, https://www.nytimes.com/1923/09/16/archives/last-of-lees-old-guard-tells-of-the-forlorn-hope-general-mcausland.html?searchResultPosition=1

[2] Eskew, “Last of Lee’s Old Guard,” New York Times.

[3] The War of the Rebellion: Official Records, Series 1, Volume XXXVII, Part 1, 44-51, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924077728289&view=1up&seq=68

[4] “General McCausland as a Farmer,” in The Point Pleasant Weekly Register, January 30, 1895.

[5] Eskew, “Last of Lee’s Old Guard,” New York Times.

[6] National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, “General John McCausland House,” http://www.wvculture.org/shpo/nr/pdf/mason/80004031.pdf

[7] Garnett Laidlaw Eskew, “Chambersburg’s Aburning,” in American Legion Magazine, 26-27 & 62-64, September 1940.

[8] “Self-Defense is Plea of Slayer,” in the Bristol Herald Courier, October 23, 1935.

Great story very interesting

So one town, Chambersburg, was torched by southerners. Do you have any issues to the feds burning of southern towns, cities and civilian homes?

The author probably does. He probably doesn’t like the Sand Creek massacre which happened under Lincoln too. Understand that he’s only writing about McCausland and his Civil War, which included the burning of Chambersburg. Should we not read or write stories about McCausland because he burned a town down or even hid e that fact? I can’t believe you do Robert. 😉

Lyle, my point is that we rarely see the other side of the story of the Union burning, looting destroying people’s homes. I’m looking for balance, not necessarily in this article but overall.

My family never did the bitter Lost Cause thing. They used to have a Confederate flag and sword hanging in the dining room. My great-aunt, then a young woman, when asked about the War Between the States, she would joke, “Come to my parent’s house and discuss it beneath the Stars and Bars.” She meant come to my parent’s house for dinner.

A few corrections to the article. Felix Robertson was not the last surviving Confederate general, his appointment was rejected by the Confederate congress. McCausland was the last survivor.

“It was to the new state of West Virginia, with a staunch pro-Union citizenry…”. Sorry, but that doesn’t fly anymore. Half of West Virginian’s counties voted in favor of secession from the US along with the rest of Virginia, and it sent half of its Civil War soldiers to the Confederacy, the only border state that did not send most of its men to the Union. Once the war started many who had voted against secession changed their minds and went for Virginia. People totally misunderstand West Virginia because of war-time propaganda that is embedded in even the most recent Civil War histories.

You’re not wrong, but neither is the author. Robertson undoubtedly carried out the duties of a general during the war. His appointment was rejected by Congress but by many historians he is regarded a general for all intents and purposes. As for WV, half of their counties voted for secession, but only about a third of the people. The other counties far outnumbered them in population. Mason county, McCausland’s home, voted against secession as well. So, yes, it’s a misnomer to say WV was totally for the Union, but at the same time you have to acknowledge the Unionists did outnumber the Confederates, and you also have to acknowledge McCausland hailed from a very pro-Union part of the state, which I think is the author’s main point here.

Sam McCausland had already killed a man 20 years earlier when he shot Howard C. West. In 1915, he beat another farmhand, George Jeffers, to death with a shovel. He was tried and found guilty – sentenced to 10 months. However, General McCausland financed appeals and I haven’t been able to confirm that he ever spent any time in jail for the crime.