The Kraken: U.S. Grant’s Grand Strategy, 1864-1865

During the Civil War era, grand strategy consisted of a strategy and a military plan.[1] Strategy in broad terms is a comprehensive idea or set of ideas that seeks to establish a lasting solution to large-scale crises. Now, strategy, in context of war, is an all-encompassing idea or set of ideas that seeks to establish a lasting solution by coordinating the objectives of the theater(s) of war and theaters of operations with national objectives.[2] Senior officers and their staffs develop a strategy by critically considering political/military ends, political/military ways, and political/military means. From this strategy, senior military leadership then create a military plan that organizes and coordinates all the forces throughout the theater of war. The people are involved in this process by way of supporting the grand strategy.

Right now, Chapter 9 in my upcoming book, R.E. Lee’s Grand Strategy & Strategic Leadership, looks at the opposing grand strategies,1864-1865. Here is the discussion looking at U.S. Grant’s approach.

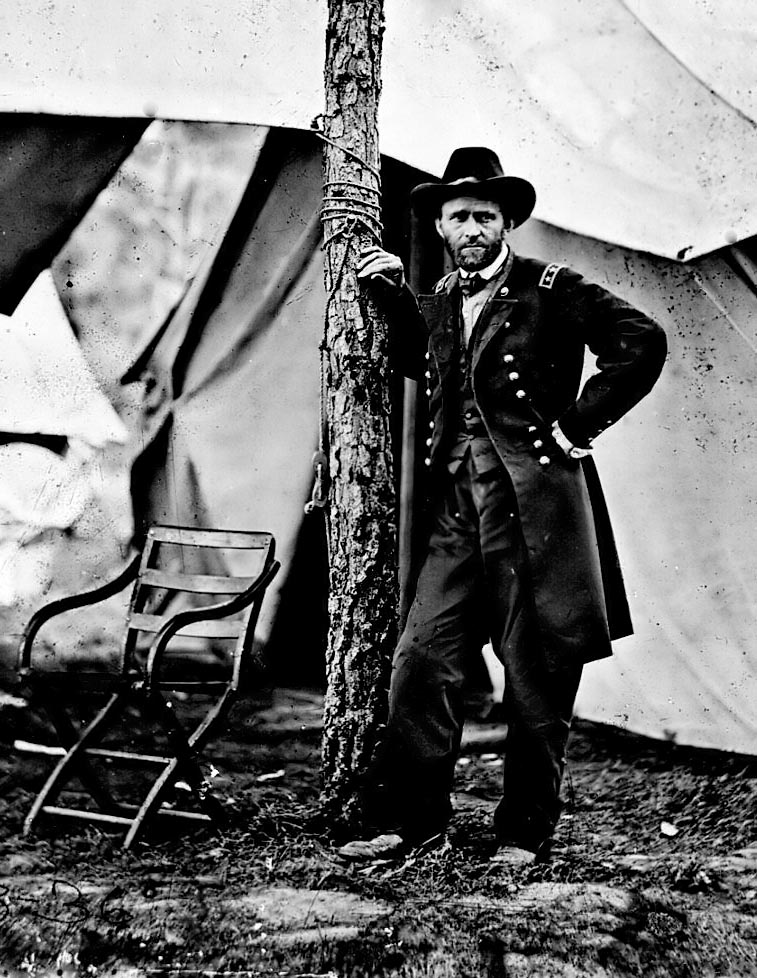

On the eve of the 1864 campaigns, the most significant difference from earlier operations was that the North had at last developed and implemented a coherent grand strategy. Behind this transformation was Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, a West Point graduate and veteran of the Mexican War. Grant’s strategy illustrated that he was not only a warrior but also a politically adroit soldier. He appreciated President Abraham Lincoln’s political goals of preserving the Union and abolishing slavery.[3] Grant also accepted Lincoln’s political/military vision—that of shattering what was left of the enemy’s resistance, in terms of both the Confederacy’s resolve and resources.[4] Thus, Grant’s military “main end” was to: a) reduce the Army of Northern Virginia’s and the Army of Tennessee’s capability and resolve to resist to an ineffective level, as well as to destroy the Southern citizens’ resolve to support the Confederacy; and, b) capture Richmond.[5] Without the means and will to resist, Southern politicians and citizens would have no option but to totally capitulate.[6]

For Grant’s strategy to succeed, however, a vital piece was needed that had been absent in the Union war effort: a military plan that strategically coordinated the operations of the Northern armies. In reflecting upon the North’s failures, from 1861–winter of 1864, Grant recounted:

“Before this time these various armies had acted separately and independently of each other, giving the enemy an opportunity often of depleting one command, not pressed, to reinforce another more actively engaged. I determined to stop this.”[7]

He put an end to this chaotic practice by thinking of the military as one unit and viewing the situation as a whole—through a theater-of-war lens, not through a theater of operations perspective as had been the case with previous commanding generals. Again, he related in his memoirs: “I regarded the Army of the Potomac as the centre [sic], and all west to Memphis along the line described as our position at the time and north of it the right wing; the Army of the James under General [Benjamin] Butler as the left wing, and all the troops south, as a force in rear of the enemy.”[8]

Four weeks before the campaigns of 1864–1865, Grant communicated his comprehensive military program to his subordinate commanding generals involved. The plan had three, corresponding parts.

- Before an active operation began commanders had to strengthen their bases of operation and guard their respective supply lines—although this component was not discussed directly, it was an inferred mission.[9]

- Once defenses were set, there was to be a simultaneous surge of all available forces against the two main Confederate armies still active in Virginia and Georgia. In support, throughout the theater of war, other operations would keep smaller opposition forces occupied, wear them down, and make them unable to reinforce these major Southern armies.[10]

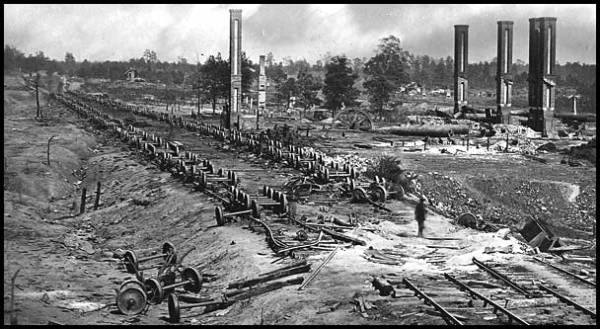

- Within each campaign, the proposal envisioned a calculated measure of destruction or appropriation of Southern stores and industries that supported the Confederacy’s war machine, whether these belonged to civilians or government agencies.[11]

Northern senior leaders understood the implication of this comprehensive directive. After reading the military plan, Major General William T. Sherman responded: “That we are now all to act on a common plan, converging on a common centre [sic], looks like enlightened war.”[12]

On paper, and when implemented, the grand strategy also resembled and acted like a Kraken. The Northern civilians/President Lincoln and General-in-Chief Grant stood at the head. The body of the sea monster consisted of five, main tentacles. Each tentacle represented a Union army that shadowed and struck a designated Confederate force. In fall of 1864, when Sherman penetrated the interior of the South, he added two more dimensions to the violence. He tore apart from the inside-out what was left of the adversary’s war machine, munitions factories and food stores. Furthermore, the march ratcheted-up the element of psychological warfare. The Southern civilian saw the North

would use its power to an awful affect against them.

In the end, the Kraken-esk grand strategy allowed Grant’s military to force the Confederates into total capitulation. It strategically reduced the Confederates’ means, e. g. killed hundreds-of-thousands of enemy soldiers and destroyed munition factories and fields of corn, cotton, and sorghum, etc. In addition, it terrorized the citizenry and demoralized the Confederate military’s willingness to fight. It was brutal, but it brought the power of resistance down to such an ineffective level that the Confederate generals had to surrender to their Union counterparts.[13] See Diagram.[14]

Sources:

[1] In contemporary terms, a grand strategy consists of a “national security strategy” and a “national military strategy”, while a “theater strategy” is linked to the grand tactical level. Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (August 2017), 162.

[2] The Joint Publication 3-0 defines strategy as “a prudent idea or set of ideas for employing the instruments of national power in a synchronized and integrated fashion to achieve theater, national, and/or multinational objectives.” Joint Publication 3-0, Joint Operations (January 2017), 214, found at http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/new_pubs/jp3_0.pdf.

[3] Grant, Personal Memoirs, vol. 2, 422–23, and 514.

[4] Grant’s reasoning is seen in his military strategy, see Ibid., vol. 2, 146–152 and 422–23. For understanding Lincoln’s desire to focus on the enemy’s armies, see T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and His Generals, 296–300, and Grant, Personal Memoirs, vol. 2, 116–18.

[5] Grant, Personal Memoirs, vol. 2, 146. For destroying, see U. S. Grant to William T. Sherman, Washington, April 4, 1864, in Sherman, Memoirs, vol. 2, 26.

[6] U. S. Grant to H. W. Halleck, Military Division of the Mississippi, Chattanooga, Tennessee, December 7, 1863, O.R., Ser. 1, vol. 31, pt. 3, 349–50.

[7] Grant, Personal Memoirs, vol. 2, 127. In March 1864, just prior to Grant taking command of all the U.S. armies, he met on separate occasions with Major Generals Meade and Sherman to discuss the strategy. It was from these conversations that Grant developed his comprehensive plan. See Sherman, “The Grand Strategy of the Last Year of the War,” Battles and Leaders, vol. 4, 247.

[8] Grant, Personal Memoirs, vol. 2, 127.

[9] Sherman, Memoirs, vol. 2, 15.

[10] U. S. Grant, Personal Memoirs, vol. 2, 129. See U. S. Grant to Major General G. G. Meade, Culpeper Court-House, Virginia, April 9, 1864, O.R., Ser. 1, vol. 33, 828, and U. S. Grant to Major General Benjamin F. Butler, Fort Monroe, VA, April 2, 1864, Ibid., 795. For out west, see U. S. Grant to William T. Sherman, Washington, D.C., April 4, 1864, Sherman, Memoirs, vol. 2, 26–7, and O.R., Ser. 1, vol. 32, pt. 3, 245–46. For further reading, see Sherman, “The Grand Strategy of the Last Year of the War,” Battles and Leaders, vol. 4, 247–59.

[11] Grant made this clear to all his generals, see Personal Memoirs, vol. 2, 129–32, 154–55, 608, and 617–18.

[12] William T. Sherman to U. S. Grant, Nashville, Tennessee, April 10, 1864, Sherman, Memoirs, vol. 2, 27, and O.R., Ser. 1, vol. 32, pt. 3, 312.

[13] The age-old concept of destroying your opponent’s means and will is succinctly discussed by Clausewitz, see On War, 77. See also, Bartholomees, “Theory of Victory,” 33–4. The U.S. has not seen an effective grand strategy implemented against our opponents since World War II.

[14] The diagram of Grant’s grand strategy is taken from my book. I wish I could draw it in 3d, but the reader will get the idea.

Excellent post integrating modern terminology. I think this highlights Grant’s real genius: his ability to understand that the military was the tool to meet the Union’s strategic and political objectives. Other Union commanders just didn’t get it.

Grant’s genius was that he recognized the tremendous superiority of Union numbers and equipment plus, unlike McClellan he did not mind losing vast numbers of these replaceable assets. His strategy is like the strategies used on the Western Front during WWI and those generals are seldom credited with genius. John

> The U.S. has not seen an effective grand strategy implemented against our opponents since World War II.

I would suggest that containment was an effective strategy against the Soviet Union, though perhaps you’re only referring to military strategies.

JoAnn’s post provides more evidence that Grant was the best military commander of the CW.

Is that because he lost more men than Lee’s army or because he ordered/allowed the terrorizing of civilians. John

Question, What is your source for this information? After researching the only civil war strategy i could find similar was ANACONDA? care to explain? im geniunely curious. This is very well written and was a swift/fast/ read!

Really interesting post, JoAnna! Well-researched and fascinating to visualize Grant’s grand strategy. I am looking forward to your book!