“On Whose Head Is This Blood?”: Union Colonels In Insane Asylums, Part 2

Part 1 of this article introduced a Union colonel who ended up being institutionalized after the war. He isn’t the only one who suffered this fate. This is a continuation of where it left off.

George Adolph Mühleck

George Adolph Mühleck was living in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and working as a language professor when he was appointed a captain in the 21st Pennsylvania Infantry in April 1861. On August 3, 1861, The German immigrant was appointed a lieutenant colonel in the 73rd Pennsylvania Infantry, and colonel of the regiment 27 days later. At the Battle of Second Bull Run on August 30, 1862, Mühleck watched as his brigade commander, Colonel John A. Koltes, fell dead when a Confederate shell killed him instantly. The brigade fell back after being “exhausted, decimated, and unsupported,” and Mühleck oversaw its withdrawal. He resigned his commission in January 1863.[1]

In December 1863, Mühleck donned federal blue again and joined the U.S. Sanitary Commission as a relief agent for the 1st Corps (later the 11th Corps). In June 1864, he took charge of the newly established Department of Shenandoah after being appointed by Dr. Lewis H. Steiner and participated in the 1864 Shenandoah Valley campaigns. The Sacramento Weekly Union reported on November 5, 1864, that Mühleck “was promptly on the field of battle [Opequon] with his corps of his assistants and stores, which were most welcome to the men and the Medical Department.” By July 1, 1865, he left the U.S. Sanitary Commission and returned to civilian life.[2]

Mühleck also made his residence in Egg Harbor City, New Jersey, sometime during the war and became active in politics and other projects, such as establishing the United States Soldiers’ and Patriots’ Orphans’ Home. He acted as the director of the Polytechnic Institute of Egg Harbor, which taught students different languages, mathematics, philosophy, chemistry, and other subjects. While making his home in Egg Harbor City, Mühleck kept close ties with his native Philadelphia, regularly traveling between the two cities.[3]

On August 10, 1865, Mühleck made the headlines when he rescued two women from drowning. The two women were swimming in the ocean while in Atlantic City, New Jersey, but ventured out too far and were pulled swap away by the tide. “The greatest consternation prevailed among those who gathered on the beach, and no one seemed willing to risk his life in saving the unfortunate couple,” Philadelphia’s City Intelligence declared. “Col. Muhleck, lately of the 73d regiment Penna. Vols., who was also present, at once plunged into the water, and after battling and struggling with the lashing waves for sometime, reached the shore bearing the insensible bodies of the young ladies.” The two women were taken to a nearby hospital and treated by a physician. Both women survived the ordeal, thanks to the heroic action of Mühleck. “Such an act as that performed by Col. Muhleck is deserving of the highest encomiums of praise,” acclaimed the newspaper.[4]

In early January 1869, Mühleck mysteriously disappeared from his residence in Egg Harbor City. On February 6, 1869, the Egg Harbor Pilot supposed that he may have had an accident in the impenetrable swamps beyond the Little Egg Harbor River, but this report was unsubstantiated. On January 13, the Bordentown Register reported that a “stranger of completely wild appearance” jumped into the Delaware River as Bordentown citizens watched in horror, fearful the man would drown. Surprisingly, the man proved to be an excellent swimmer. He then vanished into the night. The Egg Harbor Pilot suggested that this stranger may have been the missing colonel.[5]

A year went by without a word from Mühleck. On November 6, 1869, the Egg Harbor Pilot recalled how his “disappearance at that time caused considerable external excitement and had been shrouded in a mystical darkness,” but the case was now closed. The paper revealed that it received word that Mühleck had died in an insane asylum in Washington, D.C. If the colonel had died at St. Elizabeths Hospital, Mühleck would have been buried at the West Campus Cemetery. But there is no record of Mühleck’s burial there or in Egg Harbor City where his wife is buried. Fifteen years after he went missing, his farm was auctioned off and the proceeds presented to his widow.[6]

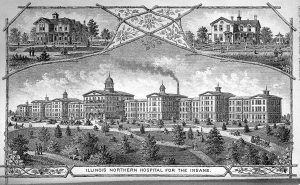

James Standiford Hull

On October 17, 1861, James Standiford Hull was appointed major of the 37th Indiana Infantry. By the end of April, Hull was promoted to lieutenant colonel. He was appointed colonel of the regiment on August 14, 1862. At the Battle of Stones River on December 31, 1862, an enemy bullet tore through Hull’s right hip and ended its trajectory near his tail bone. The ball was removed, but the wound continued to cause a shape pain in the back of his head, leading to spells of vertigo, so severe it would cause him to pass out. In addition, Hull suffered from piles, which were a result of the wound or aggravated by it.[7]

By October 1876, the colonel’s son, Walter S. Hull, a graduate of Yale, began to question his father’s sanity after receiving a long, rambling letter from him. It worried him enough to travel to Philadelphia to induce his father, attending the Centennial International Exhibition, to return home. This continued to go from bad to worse. At one point, the colonel became infuriated with his other son and attempted to attack him. His daughter Laura intervened and calmed him by cradling him in her arms as he broke down in tears. In another instance, Hull went outside one evening and danced around in his yard under the moonlight, claiming to be acting out one of John Keats’ poems. The Chicago Daily Tribute claimed that Hull’s Stones River wound was “the indirect cause of the mania.”[8]

On December 1, 1876, five weeks later, Walter reluctantly admitted his father to the Illinois Northern Insane Asylum at Elgin. The colonel tried to flee when he first arrived, accusing his son of tricking him into going, but he was restrained by several attendants. Hull continued to exhibit erratic behavior in the ensuing weeks at the asylum. “When exited, he imagined himself a soldier, in command of troops, and would give orders to other patients,” a special report noted. “If they refused to obey, he would threaten them and sometimes shake them.” At other times, he would jump behind a cover or drop to the floor, yelling, “Damn, it boys, get down! I tell you, get down! The enemy is firing upon us!” as if he was engaged in battle.[9]

On December 19, 1876, around 5 a.m., Hull got into a scuffle with an attendant named George W. Crane in a bathroom. Both slipped on the wet floor and continued to tussle on the ground. As a result of the fall, Hull fractured his leg and dislocated his ankle. Eventually, Hull was restrained. After this incident, there was some concern that Crane had used excessive force to suppress Hull, who held the colonel down by his neck despite being incapacitated by his leg injuries.[10]

Hull continued to act out violently after the incident, and it took five or six men to restrain him. Dr. Edwin A. Kilbourne, the superintendent at the Illinois Northern Insane Asylum, administered an anesthetic to calm Hull. At 6:50 a.m., Kilbourne gave him fifteen grains of chloral hydrate (a sedative) and ten drops of Magendie’s solution (morphine) but Hull vomited them up. Kilbourne then proceeded to inject Hull with another dose of Magendie’s solution. “He did not seem to come under its influence at all,” Kilbourne later reported, “struggling, raving, and his fury was extreme — wrenching and twisting every muscle in his body, and the muscles of his foot were wrenched.” After failing to take effect after 15 minutes or so, Hull was injected with some whiskey so that it would “increase the effect of the opium.” This was preceded by chloroform, more chloral hydrate, and deodorized tincture of opium. By 9:35 p.m., Hull fell asleep. His breathing soon became irregular and his heart stopped beating five minutes later. He took “one last, gasping respiration,” before passing away.[11]

Word of Hull’s death created a sensation, and Chicago newspapers insinuated malpractice as the cause of Hull’s death. The papers ran headlines such as “A Patient in the Elgin Insane Asylum Thrown Down and Maimed by Brutal Attendant,” “Pummeling Patients Not of Infrequent Occurrence,” “Finally Dies from the Cumulative Effect of Drugs Administered by the Physicians,” and “On Whose Head is This Blood?” Governor John L. Beveridge, a brevet brigadier during the Civil War, requested that the Board of State Commissioners of Public Charities investigate Hull’s death. The report that followed ruled that the conduct of the asylum’s medical staff was justified and exonerated Dr. Kilbourne of any wrongdoing. The only consolation that the Hull children had was that their father was buried in a marked grave in Chicago’s Rosehill Cemetery — a far better fate than Horner and Mühleck.[12]

Wretched Ends

Horner, Mühleck, and Hull suffered mental collapses after the war and died soon after. Of the three officers, Hull is the only one whose war experience was publicly acknowledged as the cause for his mental disability. That doesn’t mean that the war wasn’t a contributing factor or a precipitating event in the course of Horner’s or Mühleck’s illnesses. Regardless of the factors that led to their mental disability, what is apparent is that confinement emasculated these ex-army officers, strained and severed their relationships with friends and loved ones, and left them isolated to die alone or in wretched circumstances — a fate that nobody deserves, especially a soldier who served his country.[13]

Endnotes

[1] “Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866, Items Between Muhleck, George Adolph and Mulberger, Samuel,” Pennsylvania Digital State Archives, http://www.digitalarchives.state.pa.us/archive.asp?view=ArchiveItems&ArchiveID=17&FL=M&FID=1332990&LID=1333039; Samuel P. Bates, History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1 (Harrisburg, PA: B. Singerly, State Printers, 1869), 197; George A. Muhleck, U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995, Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, 1861; Public Ledger (Philadelphia, PA), September 11, 1855; “No.19: Report of Colonel George A. Muhleck, 73rd Pennsylvania,” Report of Major General John Pope, United States Army, of His Campaign in Virginia (Washington: D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1863), 121-22; John Hennessy, Historical Report on the Troop Movements for the Second Battle of Manassas, August 28 Through August 30, 1862 (U.S. Department of Interior, National Park Service, 1985), 435-36; Roger D. Hunt, Colonels in Blue: Union Army Colonels of the Civil War. The Mid-Atlantic States: Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, Delaware, and the District of Columbia (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2007), 125-26.

[2] The Sanitary Commission Bulletin, No. 13 to 24, vol. 2 (New York, 1866), 393-94, 436; “The Sanitary Commission in the Shenandoah,” Sacramento Weekly Union (Sacramento, CA), November 5, 1864; George A. Mühleck, Personnel Service Narrative, MssCol 22263, IV. Historical Bureau Records, 1861-1872 (1865-1872), C. Archive Department, 90 f. 15-16 Personnel Service Narratives, 1866, United States Sanitary Commission Records, 1861-1869 (bulk 1861-1872), The New York Public Library, Archives and Manuscripts, New York City, New York.

[3] Acts of the Eighty-Ninth Legislature of the State of New Jersey and Twenty-First Under the New Constitution (Newark, NJ: Newark Printing and Publishing Company, 1865), 829; Monmouth Democrat (Freehold, NJ), July 6, 1865; “Notice. ‘Home & Foreign Passenger & Freight Co. of North America’ in Egg Harbor City,” Egg Harbor Pilot (Egg Harbor City, NJ), April 15, 1865; Egg Harbor Pilot (Egg Harbor City, NJ), January 30, 1864; “Polytechnic Institute of Egg Harbor City,” Egg Harbor Pilot ((Egg Harbor City, NJ), July 25, 1868; “Democratic Club of Egg Harbor City,” Der Zeitgeist (Egg Harbor City, NJ), August 29, 1868; “Arrivals at the Hotels,” The Press (Philadelphia, PA), December 28, 1867. Note: A special thanks to Makali Bruton for translating these German newspapers.

[4] “Rescued from Drowning,” City Intelligence (Philadelphia, PA), August 10, 1865.

[5] Egg Harbor Pilot (Egg Harbor City, NJ), February 6, 1869.

[6] Egg Harbor Pilot (Egg Harbor City, NJ), November 6, 1869; Email correspondence with Dr. Jogues R. Prandoni, Volunteer, Saint Elizabeths Hospital; Burial records provided by Jacki Young, City Clerk, Egg Harbor City; “Notice of Sale,” Egg Harbor Pilot (Egg Harbor City, NJ), August 22, 1884.

[7] Roger D. Hunt, Colonels in Blue—Indiana, Kentucky and Tennessee: A Civil War Biographical Dictionary (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2014), 65-66; Report on the Battle of Murfreesboro’, Tenn., by Major Gen. W.S. Rosecrans, U.S.A. (Washington, D.C.: Washington Printing Office, 1863), 138.

[8] “Northern Insane Asylum,” Chicago Daily Tribune (Chicago, IL), January 3, 1877.

[9] Special Report of the Board of State Commissioners of Public Charities of the State of Illinois: In the Matter of the Death of Col. James S. Hull, a Patient in the Illinois Northern Hospital for the Insane, at Elgin (Springfield, IL: D.W. Lusk, State Printer and Binder, 1877), 5-7, 14; “The Insane Asylum,” Chicago Daily Tribune (Chicago, IL), January 25, 1877; “Northern Insane Asylum,” Chicago Daily Tribune.

[10] Special Report of the Board of State Commissioners, 8-10.

[11] Special Report of the Board of State Commissioners, 12-15.

[12] “The Hull Investigation,” Chicago Tribute (Chicago, IL), January 24, 1877; Special Report of the Board of State Commissioners 3-4, 19; St. Johnsbury Caledonian (St. Johnsbury, VT): February 09, 1877; “The Insane Asylum,” Chicago Daily Tribune; “Northern Insane Asylum,” Chicago Daily Tribune; “Alleged Malpractice,” Chicago Daily Tribune (Chicago, IL), December 22, 1876.

[13] Sarah Handley-Cousins, Bodies in Blue: Disability in the Civil War North (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2019), 9, 117, 121.

Frank, great work as usual. Your article on Egan is still one of the all-time great works on this blog.

One small correction. Col. John Koltes was killed leading his brigade on Chinn Ridge at Second Manassas, not at Cross Keys.

I recall reading that Union General Joseph Hayes died in a “sanitarium” due to mental health issues and some historians linked the illness to a wound to his head from the war. However, Hayes was in his late 70s when he was sent to the hospital and it could have been dementia or other natural causes. In other words, not related to his head wound.

Ranald Mackenzie is a tragic case. He was one of the Boy Generals of the Civil War. He graduated first in his class at West Point in 1862. Brigadier general at age 24 and one of Grant’s favorite cavalry commanders late in the war. He would go on to be one of the most successful Indian fighters, attaining the rank of brigadier general in the US Army, until mental instability and its subsequent effects killed him at age 48 in 1889.

Thanks for the kind words, Todd! And thanks for catching the Koltes error. I just corrected it.

These two posts are just heartbreaking. In all this time, we still don’t do much better for our veterans. Let us do better.