John Kelly & The St. Patrick’s Day Surprise

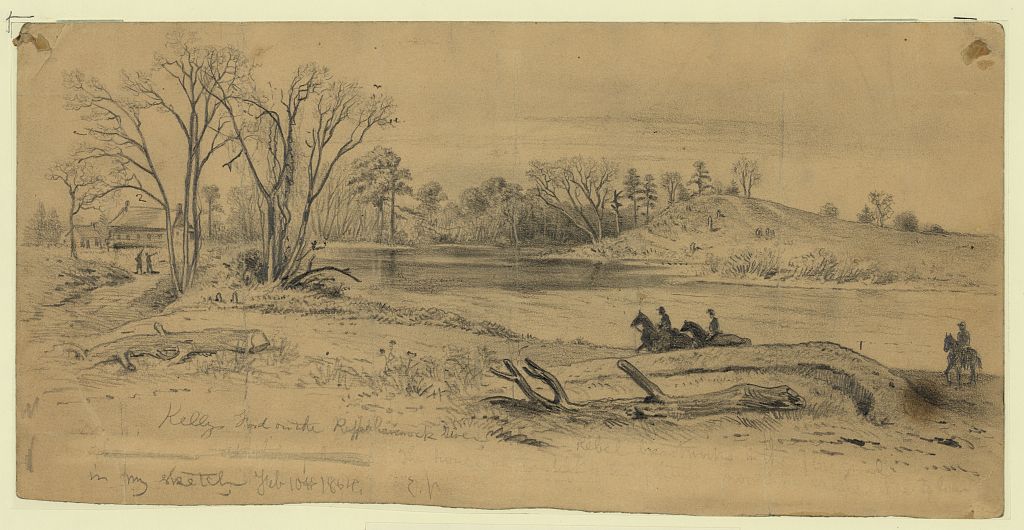

I believe civilian stories could still be “locked in the land” around Kelly’s Ford and perhaps historical resources and ruins around the area hold clues to help us understand the multiple military operations in that area. Over the last few weeks, I’ve been trying to learn more by internet sleuthing about the structures, roads, and water crossings around this area of the Rappahannock River in Central Virginia.

I believe civilian stories could still be “locked in the land” around Kelly’s Ford and perhaps historical resources and ruins around the area hold clues to help us understand the multiple military operations in that area. Over the last few weeks, I’ve been trying to learn more by internet sleuthing about the structures, roads, and water crossings around this area of the Rappahannock River in Central Virginia.

One of the most famous battles at Kelly’s Ford occurred on March 17, 1863, resulting in a marked change for Federal cavalry in the east standing up to Confederate cavalry in a direct fight. Since it’s that battle anniversary and St. Patrick’s Day, I wondered if I could find an Irish history thread to connect it all together. I didn’t have to look very far to find a piece of Irish-American history: it’s in the name of the location itself.

Kelly’s Ford. Kellysville. The name connects the location to the land owner—John P. Kelly—who was developing his own little economic empire along the river at the border of Culpeper County. According to the 1860’s U.S. Census, Kelly was born around 1789 in Westmoreland, Virginia, and some researchers have identified him as an Irishman.[i] He purchased land along the Rappahannock in 1829, eventually owning more than 1,000 acres.[ii] Over the decades, he developed the land, adding a three-story grain mill, sawmill, dye factory, shoe manufactory, and a cloth factory.[iii] His ventures were built by enslaved laborers and in 1860 the Slave Schedule (Census) lists 71 enslaved men, women, and children of all ages.[iv] The economic opportunities at Kellysville created jobs for approximately 100 laborers, both enslaved and free, creating a significant industry hub in Culpeper County.[v] According to the 1860 Census, Kelly’s, real estate was valued at $3,450 and his personal estate totaled at $51,600.[vi]

From his large mansion, Kelly could have surveyed his domain and literally watched the money roll in. He found ways to make money at every turn, which did not endear him to his neighbors, especially when he charged tolls to cross the river. One nearby neighbor accused Kelly of acting like “God on earth” and people avoided the busy businessman whenever possible.[vii] Kelly’s temper was infamous and during the Civil War, a Union soldier recorded that the old man had lost his right arm in 1862 after he furiously punched an enslaved woman in the face, resulting in a cut from her teeth which led to blood poisoning.[viii]

Union cavalrymen also recorded an encounter with John Kelly in 1862:

In like manner the mill at Kelly’s Ford was conscripted to transform rebel grain into loyal meal. At this latter ford, we found the well known John P. Kelly, then eighty-one years of age, and an invalid, formerly a very wealthy gentleman, now in a pitiable condition: his eighty negroes had escaped; his cattle and produce had been swept off by the war waves; his cloth mills had been robbed of their machinery by the Richmond authorities; and he, with a broken limb, was sick and near his grave, while “John Brown’s soul was marching on. ”[ix]

He stayed in the area after the war, and some neighbors reported that he became religious or at least donated money to help rebuild a local church building. In 1866, John Kelly died, and he was buried in a family cemetery.[x]

The Civil War ruined the structures and industries on the river banks near Kelly’s Ford, and the remains of Kellysville have slipped away or into the landscape while the woods and thick undergrowth provide a veil. The loss and vegetation growth makes it challenging to understand the precise details of the battle that unfolded on March 17, 1863, but now that I’ve been learning more about Kellysville and the man who built it perhaps additional details and clues will surface. (Or at least I have some new ideas to research in-depth when the county historical society and reading rooms are able to re-open! Stay tuned for more in future.)

One thing is certain: John Kelly didn’t collect tolls from the Union cavalry who crossed at his ford on March 17, 1863, and instead of a lucky pot of gold that St. Patrick’s Day, he found more war destruction from the battle that moved through his property.

Sources:

[i] 1860 United States Federal Census. Accessed through Ancestry.com

[ii] Brandy Station Foundation http://www.brandystationfoundation.com/cse_columns/john-kelly.htm

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] 1860 U.S. Federal Census – Slave Schedules, Culpeper County. Accessed through Ancestry.com

[v] Brandy Station Foundation http://www.brandystationfoundation.com/cse_columns/john-kelly.htm

[vi] 1860 United States Federal Census. Accessed through Ancestry.com

[vii] Brandy Station Foundation http://www.brandystationfoundation.com/cse_columns/john-kelly.htm

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Frederick Denison. Sabres and Spurs: the First Regiment Rhode Island Cavalry in the Civil War, 1861-1865, Its Origin, Marches, Scouts, Skirmishes, Raids, Battles, Sufferings, Victories, and Appropriate Official Papers; with the Roll of Honor and Roll of the Regiment. Published in January 1876. Accessed through Google Books.

[x] Brandy Station Foundation http://www.brandystationfoundation.com/cse_columns/john-kelly.htm

What a great St. Patrick’s Day story. Thank you, Sarah.

John Kelly never caught a break during the war. The cantankerous old man would fight with locals as well as his slaves, losing often.

On August 14, 1863, the Albany Evening Journal carried a small article concerning John Kelly and ice.

“-Albany Evening Journal

Ice For the Army of the Potomac – John Kelly, after whom Kelly’s Ford is named, and many other residents of Warrenton, Sulpher Springs and along the river bank, not supposing that Union troops would spend another summer on the Rappahannock, last winter laid a large supply of ice, and are troops are now using the valuable commodity. Every ice-house is honored with a guard, and each regiment receives a small piece every day. The owners have exhausted every argument to convince the commanding General the frozen water is not an article liable to be seized under a civilized system of warfare, but without success.”

Remains of his mill and mill races can be seen in the winter and early spring.

Michael, are those the same mill races as some found at the Culpeper Mine Road?

I am not sure, I have not seen the Culpeper mine races. The Kelly’s Ford mill races supported a fairly large mill, so it required a lot water to move the wheel. In the winter, you can walk the mill races. Too much undergrowth from late April until November.