On The Eve of War: Williamsburg, Virginia

In 1860 the former capital of Virginia still had many tangible remnants of its colonial past, and would become quickly swept up in the coming war. Williamsburg had 1,895 residents in 1860, with 864 black and 1,031 white. Of the 864 African Americans, 743 of them were enslaved and 121 were free.

Among the white population were a number of mechanics, and farmers, as well as lawyers and clerks, no doubt because it was the county seat. The Lunatic Asylum, as it was known, was a large employer, today it is Eastern State Hospital. There were also several merchants and coach makers. The free black population included several oystermen, house servants, shoemakers, and watermen.

With the capital’s move to Richmond during the Revolution, Williamsburg began a slow and steady decline in the nineteenth century. It was not situated on a major river, and no railroads had arrived by 1860. Other than being the county seat and having a college and mental hospital, there was little industry or other large businesses.

As the county seat of James City County, the courthouse stood (and still stands) at the center of town. In a quirk of geography, the town lay astride the border of James City and York County. Although readers might assume that the restored Colonial Williamsburg seen today resembles the quiet, rural character of the 1860 town, it does not. Many antebellum structures were removed to restore the town to its colonial appearance, and several hotels, government buildings, and private homes made Main Street more crowded in 1860 than it appears today.

Even the town’s street names were different. Duke of Gloucester Street was then called Main Street, Richmond Road was State Road, Jamestown Road was Mill Road, and the York Road was called Woodpecker Street. The town had no bank, no public school, and no telegraph office. Lacking the telegraph and a railroad connection, it was very cut off from the rest of the world, as a town would be today without internet access. There was a prominent Female Academy on the site of the old Capitol building, which had not survived the Revolution.

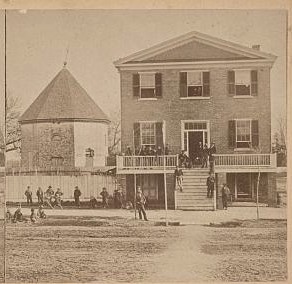

Several landmarks from its early days remained as war approached. The College of William and Mary, founded in 1693, stood at the eastern end of town. A fire had badly damaged the Wren Building in 1859 but it was repaired and classes were in session again. The old Powder Magazine, which had supplied Virginia forces in the French and Indian War, Revolution, and War of 1812, still stood, surrounded by newer buildings. Bruton Parish Church, built in 1715, was a prominent landmark, and nearby stood the ruins of the outbuildings from the Governor’s Palace. The James City County courthouse, the same building seen today in the heart of the restored area, was an important place of business. Eastern Lunatic Asylum, which had origins before the Revolution and which still survives as a state institution.

The coming war would touch many local families. Occupying a prominent house on Main Street (that still stands) was the family of Lemuel Bowden, a Unionist who opposed secession. He was a lawyer and president of the board of the Lunatic Asylum.

A little farther down Main Street lived the Barziza family, whose son Decimus et Ultimus had moved to Texas in 1857. When war broke out he enlisted there, and found himself retreating from Union forces with the Texas Brigade in front of his family home in 1862.

In the 1750s, Peter Pelham served as the organist at Bruton Parish Church, as well as the jail keeper. His grandson, John Pelham, would travel with his artillery down Main Street in front of the church in 1862. Later, he was known as the Gallant Pelham.

For 18 years, German immigrant Charles Frederic Ernest Minnegrode taught at the College and became an Episcopal minister. He introduced the Christmas tree to his Williamsburg neighbors, and in 1856 went to serve at St. Paul’s Church in Richmond, where he would later baptize Jefferson Davis.

The white residents of the community were overwhelmingly pro-secession. In fact, brothers Edward and Robert Lively, publishers of the town’s only newspaper, the Weekly Gazette and Eastern Virginia Advertiser, raised a secessionist flag over their house and printing shop at the western end of Main Street, now the pedestrian area of Merchant’s Square. Today the paper survives as the Virginia Gazette.

When war came, enlistments in the military quickly depleted the student body at the College of William and Mary. Student Richard A. Wise wrote to his Father, former governor Henry A. Wise, on January 9, 1861, “…the students here have organized a military company, and elected “Old Buck” their captain, their uniform is to be home spun pantaloons and a red flannel shirt and fatigue cap. I have joined, but do not intend to get a uniform for if there is any fighting, I am going home and go along with you. The company is to be armed with bowie knives and double barreled shot guns, or rifles, if with shot guns, they are to be loaded with buck shot in case of action…”

Subsequently on May 10, 1861, the faculty closed the school for the duration of the conflict. The College Building (Wren Building) was used as a Confederate barracks and later as a hospital, first by Confederate, and later Union forces The town would experience battle many times, and remain on the front lines for the rest of the war. One battle was fought on its eastern edge in 1862, and two more through town a year later. Union troops occupied the town for most of the war and the local men who joined the 32nd Virginia could never return home until after the conflict.

The author thanks historian Drew Gruber for his input and advice.