The Proviso and the Man

ECW welcomes back guest author Katy Berman.

Provided: That as an express and fundamental condition to the acquisition of any territory from the Republic of Mexico by the United States, by virtue of any treaty which may be negotiated between them, and to the use of the Executive to the moneys herein appropriated, neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist in any part of said territory, except for crime, whereof the party shall first be duly convicted. – David Wilmot, August 8, 1846

Unexpected historical discoveries delight the historically-minded traveler. Two such happy accidents befell me on a recent trip to Towanda, Pennsylvania. To be sure, the north-central town is not a typical destination for a winter get-away, but I was familiar with the region and needed to get out, out, out of the house.

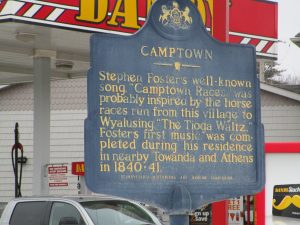

My first discovery was that songwriter Stephen Foster attended school in Towanda, and spent time in nearby Camptown. Although some musicologists question the connection, the small village of Camptown claims it was the inspiration for one of Foster’s greatest hits, “Camptown Races.” Considering that there were once horse races from Camptown to Wyalusing, five miles away, and a line from the song reads, “Camptown racetrack five mile long,” Camptown has a credible boast.

The second discovery was more poignant. On a stroll down Towanda’s Main St., an historical marker informed me that David Wilmot, “The Great Free-Soiler” died in a house across the street. It is a handsome Victorian, free from the renovations that so often mar old buildings. Gazing at his home, I was struck that I knew nothing about the man behind the Wilmot Proviso.

The Wilmot Proviso is, of course, well-known. It is praised for being the opening salvo in the war on slavery, our first step on the path to national redemption. Generations of historians have affirmed its significance and moral power. One historian concludes “the conflicting passions aroused by the Proviso most definitely proved a threat to the national parties and to the nation itself.”[1] Ironically, it was attached to a bill that was never enacted; many considered it irrelevant to the territories in question.[2] It was also introduced by a little-known, first-term Congressman who seemed, to a second historian, “to have stumbled into history and then to have slumped back into a well-deserved obscurity.”[3]

As if to underscore Wilmot’s seeming insignificance, his authorship of the Proviso is disputed. Some believe that Ohio Congressman Jacob Brinkerhoff drafted the amendment, or it might have been any of a group of men, Wilmot and Brinkerhoff included, that discussed the Proviso.[4] However it played out, Wilmot was the one who gained the floor on August 8, 1846, giving his name to a proposal that wouldn’t die.

War with Mexico had been declared May 13, 1846; Texas had become the twenty-eighth state nearly five months earlier. President James K. Polk had asked Congress for two million dollars to purchase territory from Mexico, should the opportunity arise. The vast territory Polk hoped to acquire stretched from Texas to the shining sea of the Pacific.

Northern Democrats were disgruntled that Texas had entered the Union as a slave state, while the fate of Oregon Territory, expected to be free, was still in limbo. Wilmot and other free-soil Democrats, felt betrayed by their President and their party.[5]

Wilmot introduced his Proviso, and the House passed the amended appropriations bill 107-90. The vote was ominous: for the first time, members voted chiefly along sectional rather than party lines. [6]The bill was sent to the Senate, but on that final day of the session, was not brought to a vote.

The President was appalled. He confided to his diary that the amendment was “mischievous and foolish,” because slave-holders had no wish to expand into western territories[7]. Polk met privately with Wilmot, and asked him to refrain from raising the amendment a second time. Wilmot agreed, but the standard was raised by Preston King of New York when he attached the Proviso to a new appropriations bill. The Senate refused to pass the bill with its controversial amendment.

Wilmot again championed the Proviso on February 8, 1847. His ire was directed at “the cowardice of the North” for objecting to the Proviso because it would promote disunion. Wilmot declared he was not an abolitionist; he wanted free territory for free labor. “Shall these fair provinces be the inheritance and homes of the white labor of free men or the black labor of slaves?” Wilmot demanded. [8]

The freshman Congressman had begun to make enemies. He was reelected for a second and third term, but in 1850 was rejected as his party’s nominee. However, Wilmot still had friends and supporters back home, and in 1851 was elected Judge for Pennsylvania’s thirteenth district.[9]

The Wilmot Proviso lived on in congressional debates, despite the absence of its namesake. Within the country, it created a seemingly insoluble impasse between North and South. Wilmot had blamed Northern dithering for “the aggressions of slavery.” The South castigated the North as the true aggressor, and insisted on equal rights in the territories. Voices in the North called for a holy war against slavery; the South called for disunion and a convention of southern states at Nashville[10]. Remedies were suggested: Extend the Missouri Compromise line to the Pacific Ocean, implement popular sovereignty, admit states before they underwent the territorial stage. Finally, the towering figures of Henry Clay of Kentucky and Daniel Webster of Massachusetts joined together to save the Union, and the resulting Compromise of 1850 bought peace for a few years.

Wilmot did not lose his taste for politics. In 1855, he became a founder of the emerging Republican Party in Pennsylvania, and brought his Proviso with him. At the first Republican National Convention in Philadelphia on June 17, 1856, Wilmot was made chairman of the Platform Committee. Echoes of the Proviso can be found within the Platform’s Preamble, Second and Third Resolutions. The latter states, in part: “it is both the right and imperative duty of Congress to prohibit in the Territories those twin relics of barbarism- Polygamy and Slavery.”[11]

Four years later, northern indignation was at a fever-pitch. The Supreme Court’s Dred Scott Decision and the conflict over slavery in Kansas had strengthened the Republican commitment to no slavery in the territories. On the first day of the 1860 Republican National Convention, David Wilmot was nominated as Temporary President, perhaps to give him the opportunity for delivering the “Chairman’s Inaugural.” In a stirring address, Wilmot alluded to Dred Scott, the “new dogma” that “the Constitution was established to guarantee to slavery perpetual existence and unlimited empire.” Rejecting the legitimacy of that ruling, Wilmot declared, “It is our purpose to restore the Constitution to its original meaning. . . .Slavery is sectional. Liberty, National.”[12]

The Republican Platform denounced that “new dogma” and asserted that freedom in national territories was enshrined in the Constitution. If legislation was necessary to protect that freedom, the Republican Party intended to enact it.

And so it was that on June 9, 1862, the Republican Senate passed a bill that recalled the amendment introduced by David Wilmot fourteen years earlier. “A Bill to Render Slavery Sectional and Liberty National” read “That from and after the passage of this Act, there shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in any of the territories of the United States now existing, or which may at any time be hereafter be formed or acquired by the United States. otherwise than in the punishment of a crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.”[13]

Senator Wilmot did not speak to the matter, but was able to cast a favorable vote. He had been nominated to fulfill the remainder of Simon Cameron’s term after the latter was appointed to President Lincoln’s cabinet.

David Wilmot’s health was in a slow decline during his two years in the Senate and afterwards as a Court of Claims Judge, an appointment made by President Lincoln in 1863.[14] Wilmot strove to fulfill his responsibilities, but his absences grew more and more frequent. Death came on April 6, 1868, followed by burial in a family plot overlooking the Susquehanna River.

“The Bedford Inquirer” eulogized Judge Wilmot as the “author of the famous Proviso that bears his name, one of Freedom’s boldest champions and Slavery’s bitterest foes.”[15] “The Jeffersonian” described him as “well-known from his intimate connection with the political history of our country for the past thirty years.”[16]

It may be said that after making his momentous remarks during the Twenty-ninth Congress, David Wilmot did retreat into relative obscurity. Nevertheless, he lived a life of principled endeavor and notable achievement, never losing sight of his goal to thwart the spread of slavery.

————

Katy Berman is a retired elementary-school teacher residing in New Jersey. She earned her Bachelor’s Degree in English at the University of California, Berkeley and her Master’s in American History through American Military University. For several years, she has reviewed books for “The Civil War Courier.”

[1] Holt, Michael F. The Political Crisis of the 1850s (NY: W.W. Norton and Co., 1978),50.

[2] Potter, David M. The Impending Crisis: America Before the Civil War, 1848-1861 (NY: Harper Perennial, 2011),18, 65, 68.

[3] Craven, Avery. The Coming of the Civil War (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1957),221.

[4] Foner, Eric, “The Wilmot Proviso Revisited,” The Journal of American History, Vol. 56, no. 2, (Sept., 1969), 262-264.

[5] Potter, The Impending Crisis,26.

[6] Ibid.22.

[7] Craven, The Coming of the Civil War, 220.

[8] Wilmot, David, “Wilmot Defends His Proviso,” America; Great Crises in Our History Told by its Makers, Vol. VII, The Mexican War and Slavery, 1845-1861, (Chicago: Veterans of Foreign Wars, 1925), 82-83. Google Books, accessed Mar. 18, 2021.

[9] Going, Charles Buxton. David Wilmot, Free-Soiler: A Biography of the Great Advocate of the Wilmot Proviso (NY: D. Appleton and Co., 1924),438. Google Books, Accessed Mar. 18, 2021.

[10] Potter, The Impending Crisis, 73,88. Craven, The Coming of the Civil War, 244.

[11] Greeley, Horace. Proceedings of the First Three Republican Conventions of 1856, 1860, and 1864 (Minneapolis: Harrison and Smith, Printers, 1893), 42. Internet Archive, accessed Mar. 18, 2021.

[12] Ibid. 86.

[13] Going, David Wilmot, 613.

[14] Ibid.,628-629.

[15] Bedford Inquirer, April 3, 1868 pg. 1 Vol 41, no. 14. Chronicling America: America’s Historic Newspapers Online. (Accessed Mar. 18, 2021).

[16] The Jeffersonian, pg. 2 April 2, 1868 Stroudsburg PA. Chronicling America: America’s Historic Newspapers Online (Accessed Mar. 18, 2021).

Thank you for fleshing out “this man we’ve all heard about, but could never find time to investigate.”

David Wilmot was prescient in his introduction of a Proviso to “stop the introduction of slavery to captured slavery-free Mexican territories” before the “seemingly orchestrated” war between the United States and Mexico began. And there was about to be an eruption of “filibustering,” initiated mainly by Southern interests, as attempts to wrest away control from foreign governments the “pro-slavery” bits of their territory. The most famous of these filibusters was William Walker (who took control of Nicaragua in 1856); but Cuba, Mexico, and Central America were frequent targets of filibusters during the 1800s. And it could be argued that Texas (1835-6) was the most successful of the filibuster operations, especially after the United States absorbed Texas as a state, in violation of the understanding with Mexico, in 1845.

Although the Wilmot Proviso was not adopted, its mere introduction “brought into the light” a prime reason for the anticipated acquisition of vast expanses of territory beyond the established boundary of the United States… all the way to the Pacific Ocean… and potentially, most of it below the Missouri Compromise Line of 36- 30. And the pretense of “national interest, of benefit to all” could be countered with “ambit claim of more slave territory, using Federal manpower and resources, of prime benefit to the South.” And suddenly, shadowy chameleons in Congress had to identify themselves as pro-Wilmot or anti-Wilmot Proviso. (One of these was Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri. The long-serving Senator suddenly fell out of favor over pro-Wilmot support; and Missouri politics descended into a three-way farce of vote trading and backroom deals to maintain pro-slavery Democrat control… which impacted on Bleeding Kansas… and was still “the way things are done in Missouri” when the Secession Crisis of 1860 erupted.)

Although of the Democrat Party when he introduced the Proviso in 1846, David Wilmot became a member of the Free Soil Party in time for the election of 1848. And he helped found the Republican Party in time for the 1856 election (when Fremont of Missouri, married to Thomas Hart Benton’s daughter, Jessie, ran for President… and gave the Democrat Party a scare… forecasting things to come in 1860.)

“The Wilmot Proviso is, of course, well-known. It is praised for being the opening salvo in the war on slavery, our first step on the path to national redemption. Generations of historians have affirmed its significance and moral power.”

In today’s popular narrative, opposition to “slavery in the territories” is always assigned a moral motive it simply did not have. Even when abstract moralizing was stated, it could not disguise the reality, the purpose of which was sectional segregation in America. The desire to keep slavery bottled up in the South had a racist and a political motive. Wilmont makes this racist motive crystal clear:

“It was the cause and the rights of the white freeman and I would preserve to free white labor a fair country, a rich inheritance, where the sons of toil, of my own race and color, can live without the disgrace which association with negro slaves brings upon free labor.”

“I make no war upon the South, nor upon slavery in the South. I have no . . . sympathy for the slave. I plead the cause . . . of white freemen. I would preserve for free white labor a fair country . . . where the sons of toil, of my own race and own color, can live without the disgrace which association with negro slavery brings upon free labor.”

In addition to this racist motive was a political determination to coalesce a racist North against the South by using a fabricated narrative that claimed the South wanted to expand slavery throughout the country. Lincoln used this fabrication to resurrect his moribund political career. It was nothing more than baseless racist fear mongering. The South had no desire to expand slavery into the arid climate of the territories where it would not be profitable. The institution of slavery had long reached the limits of its environmental bounds. That slavery wasn’t going West is clear when you compare the 1850 and 1860 census. In the Kansas territory the 1850 census records 66 slaves, and by 1860 only 2. Leading Southern statesmen such as Calhoun along with 40 Southern Congressmen stated clearly in a letter to their constituents that they had no desire to expand slavery into the territories:

“Their object, they allege, is to prevent the extension of slavery, and ours to extend it, thus making the issue between them and us to be the naked question, shall slavery be extended or not… So far from maintaining the doctrine, which the issue implies, we hold that the Federal Government has no right to extend or restrict slavery, no more than to establish or abolish it; nor has it any right whatever to distinguish between the domestic institutions of one State, or section, and another, in order to favor one and discourage the other. As the federal representative of each and all the States, it is bound to deal out, within the sphere of its powers, equal and exact justice and favor to all… Entertaining these opinions, we ask not, as the North alleges we do, for the extension of slavery… What then we do insist on, is, not to extend slavery, but that we shall not be prohibited from immigrating with our property, into the Territories of the United States, because we are slaveholders; or, in other words, that we shall not on that account be disfranchised of a privilege possessed by all others, citizens and foreigners, without discrimination as to character, profession, or color. All, whether savage, barbarian, or civilized, may freely enter and remain, we only being excluded.” The Address of the Southern Delegates in Congress to Their Constituents, 1849. http://history.furman.edu/~benson/docs/calhoun.htm

What the South wanted was equal access to the commonly owned territories which could not be had if a property unique to the South was banned in the territories. It was a matter of principle regarding the Constitutional mandate that all States be treated equally in the Union. The South also saw through the Northern political effort to keep Southerners from settling in the territories and eventually forming Southern allied States that might tip the balance in congress in favor of the South.

Keeping slavery out of the territories was a way to keep blacks both slave and free out of the territories, as well as Southern white voters. Lincoln made clear his racist motive regarding no blacks in the territories:

“The whole nation is interested that the best use shall be made of these [western] territories. We want them for the homes of free white people.“

“Is it not rather our duty to make labor more respectable by preventing all black competition, especially in the territories. Keeping all blacks out of the territories would free society from the troublesome presence of free negroes.”

“There is a natural disgust in the minds of nearly all white people to the idea of indiscriminate amalgamation (mixing) of the white and black races. A Separation of the races is the only perfect preventative of amalgamation, but as an immediate separation is impossible, the next best thing is to keep them apart where they are not already together.”

Horace Greeley summed up the Republican Platform:

“That all unoccupied territory of the United States and such as they may

hereafter acquire shall be reserved for the white Caucasian race, a thing that cannot be except by the exclusion of slavery.”

Banning slavery in the territories was no moral line in the sand. The very claim has a foundation built on sand! The popular narrative is politically correct fantasy!

Southerners didn’t want to extend slavery into the territories, they just wanted to bring their “property” into the territories. Sounds like a distinction without a difference. Certainly Northerners wanted free soil for free labor and feared slave labor competition. That’s a powerful economic motive, probably the most powerful incentive. Southerners rightly feared a bunch of new free states tipping the balance in Congress. Political motive. Just because Lincoln and others did not have the political space to publicly declare the moral motive doesn’t mean it wasn’t there as is also very clear from the record. Both sides demagogued the issues, so what’s new? Economic, political, moral–and yes, racial prejudices of the time underlay all. Repeatedly invoking the dreaded “R” word clarifies nothing.

Actually, let me clarify. Abraham Lincoln was explicit on the moral issue, and repeatedly so: Whatever anyone thought about their relative capability to live and work together, the African and the European (English, Irish, German, Italian, etc.) and all other persons were absolutely equal in the eyes of God and under the terms of the Declaration and Constitution. That is no “politically correct fantasy” but the bedrock principle of this nation.

I agree. “Racist” is applied indiscriminately in the present and misguidedly to the past.

Actually, it does clarify a great deal versus the mantra of moral authoritarianism of today’s rhetoric against the South. Lincoln and others certainly had the political space to declare anything they wanted to, and in fact did declare their racism and lack of humanitarian motives clearly and often. Another aspect no one seems to understand is that by taking their property in the form of enslaved persons into the Territories, Southerners moving into those Territories stood the risk of having the Territories, or portions thereof, vote to enter the Union as a free state, leaving them minus their property or having to remove. However, a careful read of Jefferson Davis and others indicates that the idea of “diffusion” was exactly this; to remove some portion of African American slaves to the Territories where they would be away from the nexus of cotton and could become freedmen as small lot farmers. The trajectory of the cotton market from 1850 to 1860 was very steep, and any reduction in those sales, or leveling off, due to competition from Egypt, etc., would have produced a significant excess supply of labor in the South, something they were trying to anticipate. There is a long and detailed history of all this, but Rod B O’Barr’s comment makes it clear that for the most part, none of the Territories were suited to slavery. The North of course knew this, so that leaves economic racism against African Americans, free or slave, as the basic issue in their campaign against slavery in the Territories, and ultimately, in the South.

You miss entirely the principled issue that was the Southern argument. Being treated differently in regards to access to the territories, regardless of the reason for the inequity, is the Southern concern. It just so happened that in relation to the territories, it involved slavery. What you claim to be a “distinction without a difference” misses the foundational principle that was the issue. The equal access of all States to the commonly owned territories was critical in the Southern mind to avoid becoming lesser polities in the Union.

Regarding your second comment, Lincoln’s abstract moralizing is a far cry from true moral concern. As Aristotle explained, true morality attaches to what one does and not mere to mere abstract moralizing. Lincoln exhibited absolute disdain for any genuine humanitarian concern for the slave. His emancipation that held no planned concern for the wellbeing of the freedmen confirms what he claimed that the EP was a “war measure.” His response at the Hampton Roads Peace Conference when asked “what would become of the freedmen” is telling – “let them root hog or die.” Regarding his American ideal of equality, he clearly stated a belief that political rights trump natural rights:

“Negro equality. Fudge! How long in the Government of a God great enough to make and maintain this universe, shall there continue knaves to vend and fools to gulp, so low a piece of demagoguism as this?”

“I have said that I do not understand the Declaration of Independence to mean that all men were created equal in all respects. I will say that I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races. There is a physical difference between the white and black races, which I believe, will forever forbid the two races from living together on terms of social and political equality. And I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.”

“Negroes have Natural Rights, although they cannot enjoy them here, and even Taney once said that ‘though it does not declare that all men are equal in their attainments and social position, yet no sane man will attempt to deny that the African upon his own soil has all the rights that instrument vouchsafes to all mankind.’”

He clearly believed that the ideal of “equality” only applied to blacks if they are “on their own soil” in Africa. His “anti-slavery” had to be reconciled with his deep racial prejudice which prevented him from allowing blacks equal rights in America. His abstract ideological moralizing is not morality at all! His racism prevented true moral action. Attempts to sanitize Lincoln are bound to failure based on the historical evidence. A recent study by a pro-Lincoln scholar found only five quotes by Lincoln, in all his massive works, that “might be construed to express a moral concern.” You have to read into those quotes a lot that is not actually expressed.

It was interesting to me that, at first, the South was little concerned about the Proviso; it was viewed, correctly, I believe, as the result of factions forming in the northern Democratic Party. Wilmot was a strong supporter of former President Martin Van Buren who was at the center of one faction. Amazingly, in 1856, Wilmot did not support Pennsylvania’s favorite son!

There was a tenuous balance in the Senate, and the South realized that free states carved out of acquired territories would upset that balance. Furthermore, there was an implication in the Proviso that the South was morally inferior to the North which would make for an interesting study.

I made no personal moral judgment regarding the Proviso; not do I consider Wilmot a racist. Wilmot left no personal papers, but what is available affirms that he dedicated his life to one principle: keeping slavery out of the territories. Through my research, I became increasingly aware of the political complexities existing in the 1840s and 1850s. Fairness requires me to keep an open mind and to keep reading!

There was widespread pre-War commentary by Northerners about Southerners being “tainted” by their close association with African Americans (lazy, immoral, uneducated, etc.). It was a common phrase at the time, leading Northerners to a general stance that Southerners had to be saved from themselves, whether Southerners were interested in this or not. For a sample of pre-War commentary, “Cotton Kingdom”, F.L. Olmsted; for a recent analysis of Northern attitudes, “Armies of Deliverance”, Elizabeth Varon, UVA.

Here is a much more balanced evaluation of David Wilmont:

https://freedmenspatrol.wordpress.com/2012/11/29/wilmot-on-the-proviso/

Wilmot’s opinions of the institution of slavery seem to have evolved; he does express revulsion toward the practice later on.

In this link, Wilmot is angry at the Northern response to his Proviso, realizing that labeling him an abolitionist would damage his position. It is important to consider the fracturing of the Northern Democratic Party in understanding Wilmot’s speech.

I am including an interesting link which is somewhat off-topic. A very respectable organization contends even today that Brinkerhoff authored the Proviso. It really can’t be proved conclusively that he did or didn’t.

https://www.newnetherlandinstitute.org/history-and-heritage/dutch_americans/jacob-brinkerhoff/

In following the track of the Wilmot Proviso and David Wilmot’s evolution of belief along the way, this 20 OCT 1860 letter from David Wilmot to Presidential candidate Abraham is revealing… especially page 2: https://www.loc.gov/resource/mal.0408500/?sp=1

And as an example of the hoops politicians will jump through in their efforts to remain relevant (or popular), here is a critique of 1844 Presidential contender, Senator Lewis Cass, and his attempt to follow the prevailing wind immediately following the introduction of the Wilmot Proviso… and his “considered re-assessment” a few months later: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=loc.ark:/13960/t4fn1974n&view=1up&seq=5

Free Soil has been compared to Nazi Germany’s lebensraum policies. The Silk Roads new world history brings this up and the fact that Hitler cited America’s westward expansion as support for his lebensraum policies… a kind of free soil for Germans.

I guess the difference is that native Americans couldn’t defend themselves like the Soviets could, and didn’t have Allied support sending them stuff to resist. I’m definitely of the opinion that native American civilization couldn’t survive Western civilization, but that in Germany and Russia’s case, western civilization couldn’t negate western civilization.

Southerners were never banned from access to any of the territories. Banning the institution of slavery from the territories would not have prevented any Southerner from moving there. Heck, if they wanted to take their slaves with them, then just free the slaves and offer them a good wage.