BookChat with Richard Miller, author of John P. Slough

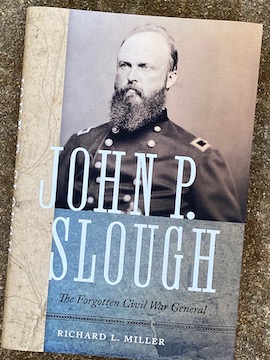

I was pleased to spend some time recently with a new biography by Richard Miller, John P. Slough: The Forgotten Civil War General, published by the University of New Mexico Press (find out more about it here). Miller is the past president of the Puget Sound Civil War Roundtable.

I was pleased to spend some time recently with a new biography by Richard Miller, John P. Slough: The Forgotten Civil War General, published by the University of New Mexico Press (find out more about it here). Miller is the past president of the Puget Sound Civil War Roundtable.

You call John Slough “the forgotten Civil War general.” For those who’ve forgotten—or never knew—him, can you give us a quick run-down?

John Slough was a mid-nineteenth century lawyer, Democratic politician, Union army officer, and judge who spent his life in a relentless pursuit of success. He crossed the continent three times seeking opportunity – from Ohio to Kansas Territory in 1857, to Colorado Territory in 1861, back to Virginia in 1862, and finally to New Mexico Territory in 1866. He is probably best known as the colonel of the 1st Colorado Volunteer Infantry, the regiment that defeated the Confederate Army of New Mexico at Glorieta Pass, but he actually had a more successful command serving as military governor of Alexandria, Virginia from August 1862 to July 1865. After the war, President Andrew Johnson rewarded him for his wartime service by appointing him as Chief Justice of the New Mexico Territorial Supreme Court. Tragically, a political rival assassinated him in 1867.

What was it that made you want to write about Slough?

What was it that made you want to write about Slough?

I first learned about Slough when I was researching a talk about the 1862 Confederate invasion of New Mexico Territory. The campaign had so many “over the top” characters – Henry Hopkins Sibley, William “Dirty Shirt” Scurry, Kit Carson, and John Milton Chivington to name a few – and Slough seemed to have led the most outrageous life of them all. He had been expelled for fighting from the Ohio legislature, was allegedly shot at by his own troops during the battle at Pigeon’s Ranch, and eventually was gunned down in a Santa Fe barroom. That’s the stuff of a great story.

But as I read about Slough, I realized that his life was a window into the great events of mid-nineteenth century United States. He not only fought in the Civil War; he also played an important role in the country’s western expansion. What’s more, a number of the key events in which he participated have been overlooked by historians. For example, he led the Democratic delegation at the Wyandotte convention, the fourth and ultimately successful effort by Kansans to write a state constitution. Despite its significance to Kansas history, the only book on the Wyandotte convention was written more than eighty years ago. Writing about Slough enabled me to tell a compelling story that would appeal to Civil War buffs, western history buffs, and biography fans as well as cover some little-trod ground in American history.

Why do you think he’s been forgotten?

From 1857 to 1867, the country’s newspapers covered Slough’s exploits relatively thoroughly; those accounts made writing his biography possible. But once the country’s newspapers covered his death in 1867, he seems to have disappeared from memory. I make the argument in the book’s introduction that Slough was probably like so many other mid-nineteenth century “go ahead” men who had a significant impact on their communities but whose achievements simply did not earn them a place in history.

Readers familiar with the 1862 Confederate invasion of New Mexico Territory may quibble with the label “forgotten” because Slough is well-known as the commander of the 1st Colorado Volunteer Infantry. Historians who have written about the battle at Glorieta Pass have treated Slough superficially. Their characterization of Slough as a “short-tempered martinet” and an officer with a “chip on his shoulder” may have contributed to his being overlooked. After all, a colonel of a far west command during the Civil War, one with a difficult personality who abruptly quit his command, does not seem like a promising topic for a book. Perhaps if Slough had left personal papers or a diary, historians would have seen a much richer life to study. Aside from Gary Roberts’s Death Comes for the Chief Justice, historians have largely overlooked Slough so that he remained forgotten until my book.

Slough served in the political trenches in the fight against Abolitionism, first in Ohio and then in Kansas. How would you characterize his position on slavery?

If only we had personal letters or a diary, we might know how Slough stood on slavery. Salmon P. Chase recorded in his diary that Slough was pro-slavery, but the positions Slough took during his term in the Ohio legislature and at the Wyandotte constitutional convention stemmed more from his conservative Democratic beliefs than any support for the institution of slavery. We can be sure that he opposed any effort to extend rights to Blacks because, as he said during the Wyandotte convention, “Nature’s God” had stamped “inferiority” on them. Yet during his time as military governor of Alexandria, Virginia, he watched recently enslaved Blacks build lives for themselves, Black laborers contribute to the Union war effort, and Black soldiers die in Alexandria hospitals. This experience changed his attitude. As Slough was preparing to hand Alexandria’s governance back to the civilian authorities, he urged the town’s leaders to repeal the old slave laws and ensure basic rights to its Black citizens – a remarkable transformation for a man who had previously embraced the most conservative positions on race.

He seems to exemplify the very idea of westward expansion: the old Northwest Territory, Kansas, and then by the eve of the war, Colorado. Afterwards, on to New Mexico. What was it about the west that kept drawing him onward?

At some basic level, Slough understood that the west meant opportunity. As a child, he must have heard his family’s stories: how both his grandfathers crossed the Alleghenies in the early 1800s, looking for opportunities to better their circumstances. He grew up on the bustling Cincinnati waterfront in the 1830s and 1840s where he watched steamboats laden with passengers and cargo headed for western ports on the Ohio and the Mississippi. And his father, Martin, imbued young John with the lesson that booming western cities, like Cincinnati, afforded an ambitious and hard-working man with many opportunities to get ahead in life.

So, you could say that moving west to seek opportunity was bred into John Slough. His ear would have been tuned to the tales the newspapers repeated in the 1850s about energetic men prospering in the rich lands of Kansas Territory or the gold fields of the Rockies. And he personally knew men who preceded him to Kansas and Colorado to seek their fortune in the West.

As much as his family history or his acquaintances might have led Slough west, it was also his disappointments that pushed him there. After the Ohio legislature expelled him and the Cincinnati voters rejected him in early 1857, Slough no longer had prospects in Cincinnati that matched his ambitions. Moving west made sense. Four years later in Leavenworth, he found himself in the same circumstances; his political career had stalled and his legal practice in land transactions devastated by the 1860 drought. Denver beckoned. Even his final move to New Mexico Territory in 1866 was preceded by disappointment when President Andrew Johnson failed to appoint Slough as governor of Colorado Territory. Slough was determined to achieve and, to him, the west offered the next opportunity for success.

Slough led Federal forces at the battle of Glorieta Pass, which you characterize as a pivotal engagement. Why was that fight so important?

If the Federal forces had not turned the Confederates back at Glorieta Pass, only the undermanned and poorly situated Fort Union would have stood in the way of the Texans and Denver. Instead, unable to replenish their supplies by capturing Fort Union, the Confederates had to retreat to Santa Fe and eventually Albuquerque. And because the Federals had been so thorough in destroying supply depots throughout New Mexico Territory, the Confederate commander soon realized that his forces did not have the arms, ammunition, and materiel necessary to continue the campaign.

It’s fun to engage in a bit of counter-history in thinking about the Federal victory at Glorieta Pass. What might have happened if the Confederates had crushed Slough’s divided command? The Union hold over Colorado Territory and New Mexico Territory was extremely tenuous in early 1862. It is not hard to imagine that the Texans might have extended the Confederate Territory of Arizona north into Colorado Territory. Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona’s mineral wealth would then have been at the disposal of the Richmond government. And the Confederates would have controlled territory on the western flank of Kansas. I realize that because of logistical difficulties, the Confederates could never have maintained a southwestern empire for long, but who knows what boost a successful New Mexico campaign might have given the Confederacy.

You argue that Slough was his own worst enemy. Why so?

Success for Slough ebbed and flowed throughout his life. His many strengths enabled him to capitalize on opportunities time and again, only for his personal failings to wreck what he had accomplished. Impulsivity, hypersensitivity, and arrogance plagued him throughout his life, leading to short-sighted decisions that cut off possibilities for advancement. At the height of his career, serving as chief justice of the New Mexico Territorial Supreme Court, a series of violent, angry outbursts led him to the confrontation that ended his life. Slough’s personality defects seemed to defeat him just about every time he appeared to be on a path to success.

How might things have turned out differently had Slough not made so many enemies or had he lived longer?

Truthfully, I have a hard time imagining his life turning out differently. He had a penchant for making enemies who actively sought his undoing. His unbridled ambition, his devotion to the Democratic Party, his stiff-backed adherence to his principles, his hair-trigger anger were all factors in his attracting enemies. Unfortunately, some of his opponents were also true scoundrels, men like John Chivington and Herman Heath, who were unscrupulous in their efforts to bring Slough down. Even if he lived longer, both his enemies and his habit of shooting himself in the foot would have ruined his chances for great success.

And here are a few short-answer questions:

What was your favorite source you worked with while writing the book?

That I could easily search scores of digitized historical newspapers made researching Slough’s life possible. Mid-nineteenth century editors and newspaper correspondents had a wonderful way with words, which made their reporting of Slough’s activities a pleasure to read.

Who, among the book’s cast of characters, did you come to appreciate better?

John Milton Chivington. He was such a ruthless cad.

What’s a favorite sentence or passage you wrote?

From a writing perspective, I really like my re-telling of the Pottawatomie Creek massacre in May 1856. A historian friend of mine told me that he had no idea the murder of the five pro-slavery settlers had been so gruesome.

What modern location do you like to visit that is associated with events in the book?

Hands down, Santa Fe, New Mexico. I’ve visited Santa Fe at least a dozen times over the last twelve years, and I never get tired of its mix of cultures and its outstanding food!

What’s a question people haven’t asked you about this project that you wish they would?

How do you write a biography about a person who left no diaries, journals, personal letters, or other personal papers?

Fascinating interview. Thank you, Chris. Having been to Glorietta Pass, I had already purchased this book. Will have to move it up on my backlog list of books to read! Civil War Books and Authors has done a fine review of the book.

Glorieta Pass is on my bucket list of CW places I most want to see. Talking to Dick almost made me buy a plane ticket to Santa Fe!

Great interview, especially as i want to ask Mr. Miller’s last question regarding a project I’m working on: how do you write a biography of a general who left no diary, no personal papers and appears to have written no letters with any personally revealing content?

Dan, I’m glad you liked the interview. To the question about how I wrote Slough’s biography without personal papers, I was fortunate that newspapers covered his exploits pretty thoroughly. Official records, like legislative proceedings or the OR, contributed a great deal of material as well. But a key piece of advice was given to me by Professor Steve Ross, who teaches at USC. Ross reminded me several times that I was the expert on John Slough and that I shouldn’t be reluctant to use that expertise to extrapolate Slough’s reactions and motivations. In the end, a biographer has to make reasonable conclusions about his subject’s state of mind.

I’ve been to Glorieta Pass and did the NPS car drive tour on a cold and snowy late December day. Great stuff. Don’t tell them you are from Texas or do, and good banter may ensue.

If the Confederates had won the battle, which they would have if the Union hadn’t had used the ridge to get in their rear (poor choice of battlefield by the Confederate leader), would the Sand Creek massacre have happened later in 1863? Not that the Confederates really cared about those Native Americans in eastern Colorado, but Chivington’s Union force and Coloradans might wouldn’t have been free to do what they did. Interesting.

I just visited Glorieta Pass battlefield back in May. I would advise you to go to Pecos National Park, which we did and in itself is very interesting. Make sure that you buy the $2 trail map for both Pecos and Glorieta because you will only find numbered posts at the points of interest and have to guess at what you’re looking at. You also need a map to find the battlefield along with the combination to the locked gate. It is I believe around a 1.5 mile trail and all wooded so difficult to get your bearings. Also, supposedly there is one remaining building left from Pigeon Ranch but I never saw it through the trees. I was disappointed but still glad that I had the opportunity to visit. The best book on the battle is “The Battle of Glorieta Pass, A Gettysburg in the West”. Make sure that you read it before you go. I also read “The Three Cornered War” before going which was helpful.

I enjoyed the book, and thought your interpretation of this difficult but in some ways admirable character was well done. I am trying to investigate the equally elusive life of Loulia Slough, a very early woman lawyer who seems to have been his niece and to have followed in his footsteps to an interesting extent so I sympathise with the issues faced.