Petersburg Day One: Wednesday, June 15, 1864

On June 15 the Army of the Potomac began to cross the James River. It was an emotional moment. A. M. Judson of the 83rd Pennsylvania likened the army’s arrival at the James to Xenophon and his 10,000 Greeks reaching the Black Sea. As the 7th Rhode Island marched passed a nearby swamp a band played “Ain’t we glad to get out of the wilderness.”[i] Rufus Dawes, commander of the 6th Wisconsin and a hero of Gettysburg, wrote to his wife that “it is very refreshing to get to the beautiful slopes of this broad river.”[ii] From Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant received that morning a simple message: “I begin to see it. You will succeed. God bless you all.”[iii]

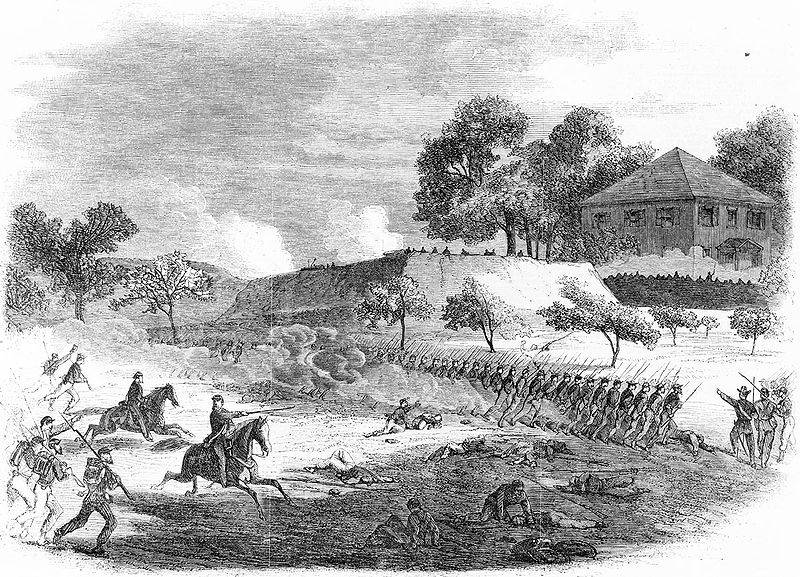

Back at Bermuda Hundred, things were less encouraging. William Smith’s XVIII Corps was scattered and he would not be able to strike Petersburg at dawn. The XVIII Corps ran into resistance almost from the moment they crossed the Appomattox River, being delayed by James Dearing’s cavalry brigade. At Baylor’s Farm, XVIII Corps ran into 850 troopers and two cannon, commanded by Dennis D. Ferebee. They faced Edward Hinks’ division of black soldiers.

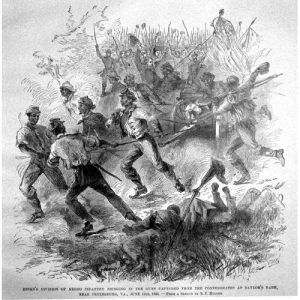

Hinks’ men were green and varied in quality of drill. Ferebee had a strong position and marshy woods lay in the middle of the field that Hinks’ troops would have to cross. The inexperience of the black troops led to confusion and their lines were broken up by the marshy underbrush, while Rebel fire was disciplined and accurate. Some Union regiments even fired on each other and many broke. Yet the 22nd USCT managed to press ahead and capture a cannon. Losses though were lopsided. The Confederates lost one cannon and the 4th North Carolina Cavalry reported nine casualties, including a wounded Ferebee. Union losses were 300, but the captured cannon made Hinks’ men rejoice.

Back in Petersburg, Henry Wise mustered his troops while bells tolled to call out the militia. He brought the city’s convalescents to the front. Guards were posted along the roads with orders to arrest any soldier trying to leave the city. In Wise’s uneven career, June 15 was his high point. Still, Wise had to cover miles of trenches with 3,000 men, although the defenses, known as the “Dimmock Line,” were strong. Beauregard immediately surmised that Smith’s advance was a full attack and he ordered Robert F. Hoke’s division to Petersburg. Wise’s only advantage was in artillery. He had some twenty-five cannon, including a few heavy pieces.

Smith was unnerved by the heavy losses at Baylor’s Farm. He paused for a time before moving on Petersburg, his men arriving slowly. It was not until 2:00 p.m. that every unit in XVIII Corps was up and ready for battle. As the Union regiments formed up, William Russell of the 26th Virginia observed that “we had such a small force here it made me tremble to see them.”[iv]

As the lines formed, August Kautz’s cavalry moved on the Baxter Road to the south. By 5:30 p.m., Kautz’s skirmishers were out of bullets and he decided to fall back. Only forty-three men were casualties, although among them was Simon Hoosick Mix, one of Kautz’s brigade commanders. Mix’s men tried to rescue him, but he told them to save themselves. He apparently once said he prayed to die while leading the 3rd New York Cavalry in a glorious charge. The attack of June 15 was more bungling than glorious, but Mix got his the second half of his wish. Without medical care he perished on the field.

While Kautz was wasting time, Smith scouted the ground. This was made difficult because Smith was still recovering from the dysentery that he had contracted at Cold Harbor and he moved on foot in the heat. After two hours he surmised that the Dimmock Line was an impressive position, but lightly held. He would attack all along the line and spent the next two hours conferring with his division commanders and planning. Smith decided the first line would advance in a loose formation, a pace apart from each other, to avoid heavy losses. The second line would be arrayed for a heavy assault.

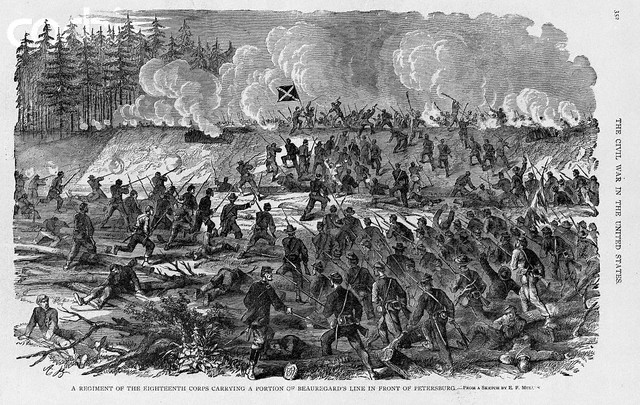

The Union artillery opened up just after 6:20 p.m. The barrage was effective in confusing the Confederates and silencing their guns. After roughly twenty minutes, XVIII Corps advanced. The attacks along the Appomattox River were a limited success but Jordan’s Hill was overrun. N.A. Sturdivant, who commanded the artillery on Jordan’s Hill, openly lamented that his men were “captured by a Yankee skirmish line.”[v] In total 227 Rebels, including sixteen officers, capitulated. The flag of the 26th Virginia fell into Union hands, along with five artillery pieces.

Even more impressive was Hinks’ attack. Christian Fleetwood, a free black businessman of the 4th USCT, boasted “swept like a tornado over the works.”[vi] In two hours of nearly constant fighting, the USCT regiments, relatively green before June 15, had carried nearly a mile of enemy trenches. They cheered their victory and yelled “Fort Pillow!”[vii] The path to Petersburg was wide open.

Smith, who had been dismissive of the USCT beforehand, praised them highly in his official report and declared that they had “no superiors as soldiers.” Smith personally congratulated Hinks, telling him “this is a stronger position than Missionary Ridge.”[viii] After hearing of their success John Rawlins dropped his opposition to using the USCT in pitched battles. Petersburg was the first time black troops had been actively used in the bloody fields of Virginia and they had exceeded expectations. Ironically, this triumph came on the same day that the House of Representatives failed to pass the thirteen amendment, which would have abolished slavery in its entirety.[ix]

Smith had been successful, but with the sun setting he grew cautious. Smith made no effort to advance into the tangled ravines, hills, and woods that lay before him. He was also sure Robert E. Lee was on the way. In addition, Smith likely lost around 1,400 men on June 15, which was no pittance.

Winfield Scott Hancock’s II Corps arrived on the field just as Smith’s attack began. He should have been there sooner, but Grant failed to inform him that Petersburg was the target, and Hancock waited hours for orders. The maps were so poor that Hancock had to rely on local black guides to find Petersburg. Despite these problems, II Corps made good time, advancing fourteen miles in a little under five hours. He arrived with the divisions commanded by David Birney and Francis Barlow, two proven fighters.

II Corps was not pitched in. The men were in a ragged state. James McDonald of the 5th New Hampshire wrote “There was a rage amongst us for water; the burning thirst should be satisfied, and many of the men were seized with diarrhoea. But military necessity knows no obstacles save those of the enemy…we rested our weary limbs within about two miles of the doomed city of Petersburg, having marched something like twenty-one miles.”[x] Furthermore, Grant stated, “If Petersburg is not captured tonight it will be advisable that you and Smith take up a defensive position and maintain it until all the forces are up.”[xi] These were hardly words meant to inspire an all-out drive on Petersburg.

Smith did not believe a night attack was sound, even with a full moon. Hancock, his superior in rank and now in overall command, agreed with him and wanted to press on in the morning. II Corps spent the night taking up position at Jordan’s Hill, thereby allowing Smith to withdraw some of XVVIII Corps. This however meant that II Corps was no longer in a good position to outflank Beauregard’s men. Some soldiers yelled “Put us into it, Hancock, my boy; we will end this damned rebellion to-night!”[xii] The high command though remained unfazed.

Smith possibly saw the battle as all but won. He informed Benjamin Butler around midnight that “It is impossible for me to go further to-night, but unless I misapprehend the topography, I hold the key to Petersburg.”[xiii] Smith seemed to forget the real lesson of Cold Harbor: if given sufficient time, the Confederates could erect nearly impregnable entrenchments. Butler later wrote, “Smith says…he held the key to Petersburg. True, he did; but what is the use of holding the key when you have not the courage to turn it in the lock?”[xiv]

Meanwhile, Grant and Meade offered a study in contrasts on June 15. In a letter to his wife Julia, Grant said, “A few days now will enable me to form a judgment of the work before me. It will be hard and may be tedious however. I am in excellent health and feel no doubt about holding the enemy in much greater alarm than I ever felt in my life.”[xv] While these words were optimistic, they no longer reflected the fighting spirit of his dispatches from Spotsylvania. By contrast, once Meade heard of Smith’s success he stopped his dinner and gave new orders to speed along the march of V and IX Corps to Petersburg.

Beauregard arrived at Petersburg at 6:00 p.m. and while inspecting the lines witnessed the flight of Wise’s command. He set up his headquarters at the Customs House and set about organizing the city’s defenses. Losses were about 400 for the day and two regimental commanders had been captured and another was wounded. Wise’s brigade was battered but still capable of combat. Meanwhile Johnson Hagood, representing the vanguard of Hoke’s division, arrived. The citizens of Petersburg cheered and some wept declaring, “We are safe now.” By morning Beauregard would have around 10,000 men.[xvi]

Beauregard needed more men. He asked Braxton Bragg, Jefferson Davis’ military advisor, whether he was to hold the Howlett Line at Bermuda Hundred or Petersburg, since he could not hold both. Bragg told Beauregard to use his judgment. At 10:25 p.m. he ordered Bushrod Johnson to abandon the Howlett Line.

To the North, Lee remained fixed on protecting Richmond, even when A.P. Hill informed him that he only faced a cavalry screen. Beauregard could only confirm the existence of the XVIII Corps. Lee sent to Beauregard one brigade and four batteries but no more. Lee wrote that night “Nothing else of importance has occurred to-day.”[xvii] Although Bragg and Lee were not too worried about Petersburg, J. B. Jones, a clerk in the war department, did see the situation for what it was. He assumed that Grant was swinging at Petersburg with most of his army and after the fighting on June 15 he wrote “The war will be determined, perhaps, by the operations of a day or two; and much anxiety is felt by all.”[xviii]

————

[i] William P. Hopkins, The Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers in the Civil War 1862-1865 (Providence: Snow & Farnham, 1903), 90.

[ii] Rufus R. Dawes, Service with the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers (Marietta: E. R. Alderman & Sons, 1890), 290.

[iii] Butler, Private and Official Correspondence of Gen. Benjamin F. Butler, Vol. IV, 373.

[iv] Howe, Thomas J. The Petersburg Campaign: Wasted Valor, June 15-18, 1864 (Richmond: H. E. Howard, 1988), 31.

[v] S. Millett. Thompson, Thirteenth Regiment of New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry in the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865 (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1888), 390.

[vi] Edward G. Longacre, A Regiment of Slaves: The 4th United Stares Colored Infantry, 1863-1864 (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2003), 91.

[vii] Williams, A History of the Negro Troops in the War of the Rebellion, 238.

[viii] Thomas L. Livermore, “The Failure to Take Petersburg, June 15, 1864.” In Papers of the Military Historical Society of Massachusetts: Petersburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg. (Boston: Military Historical Society of Massachusetts, 1906), 68.

[ix] Charles A. Dana, Recollections of the Civil War: With the Leaders at Washington and in the Field in the Sixties (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1899), 220.

[x] Letter from the 5th New Hampshire Vols.” Irish American Weekly. July 16, 1864

[xi] Grant, The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Vol. XI, 53.

[xii] Frank Wilkeson, Recollections of a Private Soldier in the Army of the Potomac (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1887), 160.

[xiii] Butler, Private and Official Correspondence of Gen. Benjamin F. Butler, Vol. IV, 383.

[xiv] Benjamin F. Butler, Autobiography and Personal Reminiscences of Major-General Benjamin F. Butler (Boston: A. M. Thayer, 1892), 690.

[xv] Grant, The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Vol. XI, 53.

[xvi] Thomas, “The Slaughter at Petersburg June 18, 1864,” 224.

[xvii] Richmond Examiner, June 17, 1864.

[xviii] J. B. Jones, A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary Vol. II (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Company, 1866), 232-33.

So near and yet so far…