Recruiting the Regiment: The 11th New York Fire Zouaves

A post-script to the recruitment blog series…

“I want the New York firemen, for there are no more effective men in the country, and none with whom I can do so much. They are sleeping on a volcano at Washington, and I want men who are ready at any moment to plunge into the thickest of the fight.” [i]

On April 18, 1861, 24-year-old Elmer Ellsworth pleaded with Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, to allow him to recruit in New York City. In addition, Ellsworth held out a personal letter of recommendation from President Abraham Lincoln to strengthen his case, assuring Greeley of his integrity. This incident is the beginning of the 11th New York Fire Zouaves’ story as one of the first regiments recruited and sent to Washington after Lincoln’s initial call for troops.

By April 15, 1961, when Abraham Lincoln put out a national call for 75,000 troops, Elmer Ellsworth took action so quickly that it became evident he had already decided what he would do when this time came. He resigned his hard-won second lieutenant’s commission and went directly to the White House to speak with Lincoln. Once there, he explained his plan to go to New York City and raise a regiment among the New York firemen, bringing them back to Washington to fight with the regular army. Lincoln gave Ellsworth an open letter of introduction to take with him, again displaying Lincoln’s regard for the young man and establishing broad privileges for Ellsworth in Lincoln’s name:

To Elmer E. Ellsworth

Col. E. E. Ellsworth

Washington, April 15, 1861

My Dear Sir:

Ever since the beginning of our acquaintance, I have valued you highly as a personal friend, and at the same time (without much capacity of judging) have had a very high estimate of your military talent.

Accordingly I have been, and still am anxious for you to have the best position in the military which can be given you, consistently with justice and proper courtesy towards the older officers in the army. I cannot incur the risk of doing them injustice, or a discourtesy; but I do say they would personally oblige me; if they could, and would place you in some position, or in some service, satisfactory to yourself.

Your Obt. Servt.

A. Lincoln [ii]

Ellsworth decided to recruit New York firefighters based on several good reasons, coupled with personal experience. Earlier, he had been instrumental in the choosing and training of three hundred men in Chicago for the Chicago Fire Brigade. He knew that firefighters were trained to work together as a single unit, each doing his duty but keeping an eye on the men around him. They could respond quickly, obey orders, organize, and execute upon command. Ellsworth believed men with these attributes would make good soldiers. With Greeley’s help and encouragement, Ellsworth immediately placed ads in newspapers and blanketed the city with posters. Two days after arriving in New York, he awarded officer commissions to New York City Fire Company leaders and to former members of the U. S. Zouave Cadets, several of whom had agreed to help him in his endeavor. Then Ellsworth began recruiting in earnest.

Ellsworth decided to recruit New York firefighters based on several good reasons, coupled with personal experience. Earlier, he had been instrumental in the choosing and training of three hundred men in Chicago for the Chicago Fire Brigade. He knew that firefighters were trained to work together as a single unit, each doing his duty but keeping an eye on the men around him. They could respond quickly, obey orders, organize, and execute upon command. Ellsworth believed men with these attributes would make good soldiers. With Greeley’s help and encouragement, Ellsworth immediately placed ads in newspapers and blanketed the city with posters. Two days after arriving in New York, he awarded officer commissions to New York City Fire Company leaders and to former members of the U. S. Zouave Cadets, several of whom had agreed to help him in his endeavor. Then Ellsworth began recruiting in earnest.

In 1861, like all other large cities at the time, New York’s fire department was a volunteer organization staffed by “B’hoys” from a variety of backgrounds who responded when their district’s fire tower sounded an alarm and “ran with the masheen” to the site of the fire. The physical exertion required to run a huge fire engine through the streets, pump water, climb ladders, and pull hoses meant that the volunteers were generally in good physical shape. The New York City men had earned a mixed reputation, being known for fighting among themselves as much as for fighting fires. Although these rough b’hoys were of varying political viewpoints and, like many New Yorkers, may have initially felt sympathy toward the South, the attack on Fort Sumter caused New York to fall firmly in line on the side of the Union.

Within three days of his arrival, Ellsworth had at least 1,200 men signed up for a tour of duty lasting ninety days. The New York Leader, April 27, 1861, printed a fantastic compilation of Ellsworth’s efforts:

Colonel Ellsworth and his officers have been active in preparing this regiment for service. More work has been done in six days than seemed possible. The men have been mustered into service; the officers elected; the uniforms made, and on Sunday afternoon, eleven hundred as efficient and hardy soldiers as ever handled a gun, will start for the scene of rebellion.

Col. Ellsworth arrived in this city on Thursday of last week. On Friday he called together a number of the principal men of the department. On Saturday he selected his officers. On Sunday he mustered one thousand men. On Monday he drilled them. On Tuesday inspected them. On Wednesday commenced giving them clothes. On Thursday had them in quarters, and yesterday, (Friday), he was ready and waiting for supplies. Today he will receive them, and to-morrow march through the city escorted by the whole Fire Department on board the steamer Baltic direct for the seat of war. [iii]

Ellsworth was immediately elected Colonel of the Regiment, and the former Zouave Cadets who were working with Ellsworth began drilling the volunteers. The following two days brought the enlistments up to 2,300, enough for two entire regiments. New York State could not arm that many nor provide uniforms for them. Additionally, although not every volunteer was also a firefighter, enough were that New York City began to be concerned that its fire fighting preparedness would be severely compromised if this many firemen left the city at once. By combining hard drilling and accurate physical examinations by the company’s Surgeon, Doctor Charles Carroll Gray, who had served in this capacity in the British Army during the Crimean War, cut the total to 1,100 men. There were rumors that a few of the b’hoys had been “g’hirls,” but there is little to document this rumor.

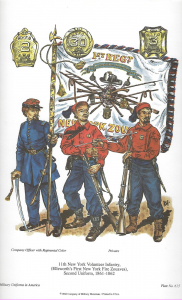

The patriotic citizens of New York City raised about $60,000 to purchase rifles for the troops, although the actual guns, which were supposed to be Sharps Rifles, turned out to be an assortment of at least ten different kinds of firearms. They were gladly received, however, and served the immediate purpose. Ellsworth had designed the volunteers’ uniforms to be sewn in red, blue, and gray worsted wool. These were paid for by subscription and put together quickly as contract work. However, later, the uniforms were not made of worsted wool at all, but a substance made of cutting room floor scraps cut into bits and, with glue, felted together. This was referred to as “shoddy,” and it began to fall apart quickly. Ellsworth, Lieutenant Stephen W. Stryker, and Quartermaster Alexander M. C. Stetson were rightly appalled at this deception and worked hard to remedy the condition.

The patriotic citizens of New York City raised about $60,000 to purchase rifles for the troops, although the actual guns, which were supposed to be Sharps Rifles, turned out to be an assortment of at least ten different kinds of firearms. They were gladly received, however, and served the immediate purpose. Ellsworth had designed the volunteers’ uniforms to be sewn in red, blue, and gray worsted wool. These were paid for by subscription and put together quickly as contract work. However, later, the uniforms were not made of worsted wool at all, but a substance made of cutting room floor scraps cut into bits and, with glue, felted together. This was referred to as “shoddy,” and it began to fall apart quickly. Ellsworth, Lieutenant Stephen W. Stryker, and Quartermaster Alexander M. C. Stetson were rightly appalled at this deception and worked hard to remedy the condition.

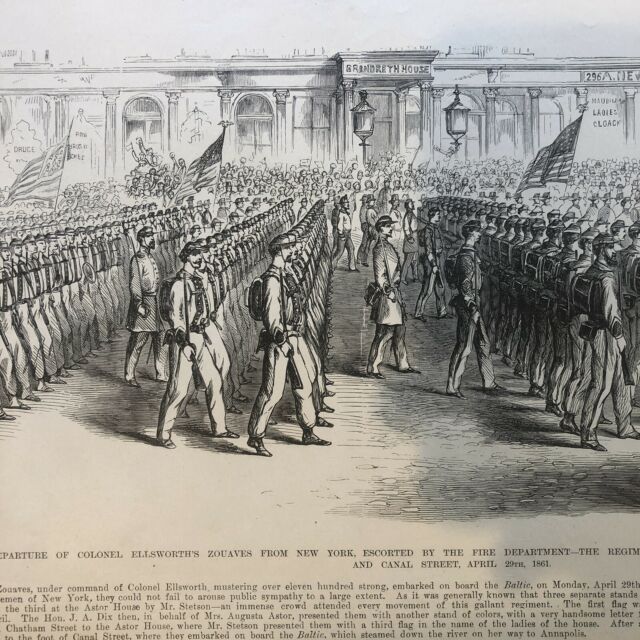

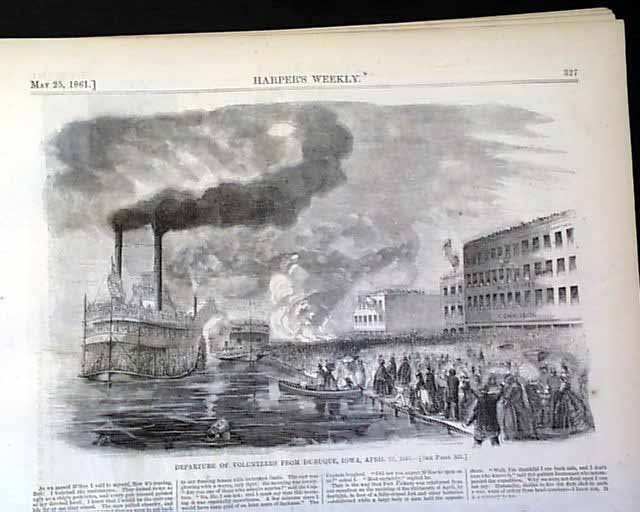

Several military units left New York City for Washington between April 19 and 29—the Sixth New York, The Fifth and Eighth Massachusetts, and even the famous Silk Stocking Brigade–the Seventh New York–darlings of the wealthy. It is doubtful, however, if any regiment created the excitement of Ellsworth’s Fire Zouaves. The Zouaves left New York City on April 29 amid colorful, emotional celebrations.

All the prominent newspapers sent reporters to the Devlin Building on Canal Street, where the 11th was quartered, to report their departure. From the New York Evening Post:

The headquarters just previous to the departure at 2:45 PM presented a scene of extraordinary activity as the men were marched by companies into the basement of the building to receive their arms, which consisted of Sharps rifles and knives—a sort of bowie-knife about 16 inches long, sometimes called an “Arkansas toothpick,” which fitted the rifles and could be used as a bayonet—and revolvers. [iv]

Ned House of the New York Tribune wrote:

Inside the building, everything wore a military business-like air; many soldiers were packing their knapsacks, fitting their belts and uniforms, while others were undergoing a preliminary drill under the directions of their enterprising captains. The busiest man of the whole regiment, however, was Col. Ellsworth himself. . . . His step was as brisk and his voice as deep and sonorous as when New Yorkers first beheld him at the head of his famous company of Chicago Zouaves. One moment . . . the little Colonel . . . was marching at the head of an enthusiastic company of butcher boys, the next he would be assisting a colored servant to carry a box of muskets across the room, or buckling the knapsack to the broad shoulders of some volunteer who “hadn’t exactly gotten the hang of the infernal contrivance.” [vi]

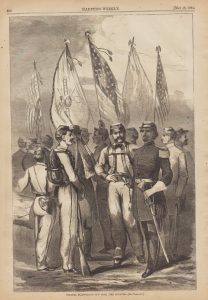

When the Fire Zouaves lined up on Canal Street, the final ceremonies began. Mr. W. H. Wickham, President of the NYC Fire Department, presented the regiment with a large, white silk flag, bordered with a tri-colored fringe of red, white, and blue. Hooks, Ladders, and other firemen’s tools were embroidered in the center of the flag, and a fireman’s ax topped its staff. Wickham spoke, “When the fire bell rings in the night, the citizen rests securely, for he knows the New York firemen are omnipotent to arrest the progress of destruction. You are now . . . called to quench the flames of rebellion. Our hearts are with you, at all times and in every place.” [vii]

General John Adams Dix and Mrs. John Jacob Astor, Jr., presented the next flag, made of red silk, with General Dix reading Mrs. Astor’s letter of presentation to “the men whose heads are moved by a generous patriotism to defend it, and whose hearts feel now more deeply than they have ever done that the honor of their country’s flag is sacred and as precious to them as their own.” [viii]

The third flag was presented as a gift from actress Laura Keene. Ms. Keene’s letter was addressed to “Brother Soldiers.” Many more flags, flowers, and banners were presented until, loaded with laurels, the Zouaves and several bands began marching down Broadway to the pier where the steamship Baltic was waiting to take them to Annapolis. There they would proceed to Washington by train.

In the words of Arthur O’Neil Alcock, a volunteer Zouave and “Special Correspondent” for the New York Atlas:

Finally, the last good-bye having been uttered, the last hand shaken, the fasts were let go, and the noble Baltic glided from the pier out into the broad stream, amidst the deafening cheers of the multitude that had accompanied us . . . flags were run up to the peaks and mast-heads, bands played, the ‘Star Spangled Banner’ waved proudly in the breeze, the flag of the Fire department floated out in all its beauty . . . and we were away! Still, however, as the cannon boomed the parting salute, anxious eyes were kept on the docks lined with the red shirts and leather hats of our comrades left at home, and the tears might be seen in the eyes of brave and stalwart men. [ix]

And so the short career of the 11th New York Fire Zouaves began.

_______________________________________________

[i] Schroeder, p. 22.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Ibid

[iv] Randall, pp. 232-235.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Randall, p. 232.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center, 11th Infantry Regiment, New York, Civil War Newspaper Clippings. (NYS Division of Military and Naval Affairs). Retrieved from http://dmna.state.ny.us/historic/reghist/cicil/infantry/11thinfCWN.htm

[ix] Randall, p. 230 and About.com, Col. Elmer Ellsworth Became a Legend and Martyr Early in the Civil War. Retrieved from http://history1800s.about.com/od/civilwar/ss/Death-of-Elmer-Ellsworth_2.htm.

Enjoyable article.

During the 1850s young men moved to the cities to find work as clerks, laborers, mechanics and engineers. Some left family farms and a dozen siblings behind; others were new arrivals from Europe. Besides employment, these men sought a sense of purpose: many joined social organizations, such as the YMCA, and the Turnverein. Others were drawn to the rejuvenated militia organization, and the new form of drill, dress and Code of Ethics, inspired by Elmer Ellsworth during his 1859 – 1860 National Tour. The Zouave movement, embraced by serious men of purpose, North and South, helped lay the groundwork for the contest of arms that was destined to erupt in 1861. Meg Groeling is to be commended for revealing the brief, but explosive impact of Colonel Ellsworth, his movement, and his life (setting the example, and living in accordance with his code) that inspired a generation.

I hope you enjoy First Fallen, his new bio. It will be out soon, I promise. I will be on the road promoting it in a few months–cancer intervened, but time helps everything.

I remember reach

I remember reading an article somewhere on ECW about a former officer from the 11th New York who after his time with the regiment became a star player for one of the period New York base ball clubs- the Union Club of Morrisania I believe. Can anyone tell me what article that was and the officer’s name?