Soldiers of Gettysburg: Lawrence M. Whitney, 83rd New York

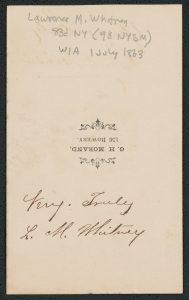

His name was Lawrence M. Whitney, and he had promoted to lieutenant in Company E in the 83rd New York Regiment. He was wounded during the Battle of Gettysburg.

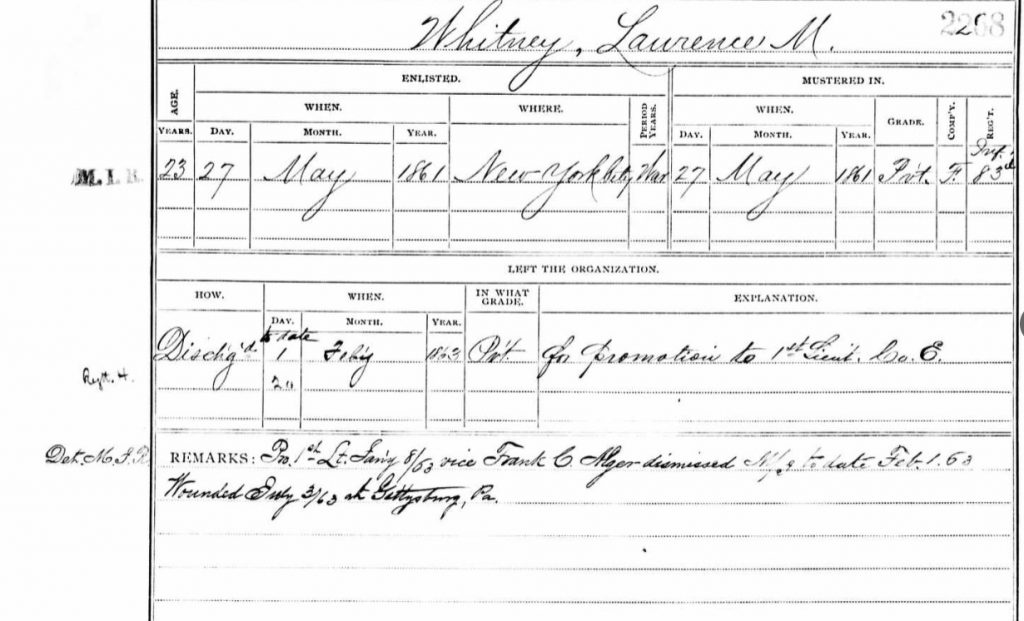

Born around the year 1838, his parents were Joseph and Emiline Whitney. At age 23, Lawrence enlisted in 1861 in New York City for three years, mustering with the 83rd New York Infantry in Company F.[i] He presumably picketed with the regiment during the first year of the war at Harpers Ferry and other points along the Potomac and fought at Second Bull Run, South Mountain, Antietam, and Fredericksburg before arriving on the fields of Gettysburg.[ii] In February 1863, Whitney transferred companies and promoted to lieutenant in Company E.

Whitney’s name does not appear frequently in the major regimental reports or histories. Veteran writers noted his promotion and Gettysburg wounded. However, they wrote about the unit’s experiences during the July 1-3 battle in Pennsylvania, giving an idea of what Whitney experienced.

In Captain Edmund Patterson’s report in the official records, the 83rd New York camped near Frederick, Maryland on June 28, 1863. The following day they marched to Emmitsburg, Maryland, and spent the night on picket duty before rejoining their brigade in the morning.[iii] The 83rd marched in the Second Brigade, Second Division of the General John Reynold’s I Corps.

John W. Jacque’s picked up the account, recording his book Three Years Campaign of the Ninth N.Y.S.M during the Southern Rebellion** that on July 1, 1863:

“About 8 A.M., taking up the line of march, on the Emmitsburg pike, to within a few miles of Gettysburg, when turning off to the westward of Gettysburg, we took the road leading to Seminary Hill, hearing heavy cannonading and musketry in that direction; nearing the hill, we found the First Division of our Corps, engaged with the rebels, our Division immediately formed on their right, back of the town, distant about three miles; Our Corps with the Third Division, which took its place in the line numbered about 7000 men, and they were arrayed against a force with three times their number, and were engaged three hours, showing the rebels that they were not the “raw militia,” that they were led to expect, but the bone and sinew of the “First Corps, of the Army of the Potomac.” After being engaged for about three hours, taking a large number of prisoners, and losing about half our men, the Corps was relieved by a portion of the Eleventh Corps, and shortly afterwards, the rebels having outflanked them, all our troops had to fall back, through the town, to Cemetery Hill, under a galling fire, and the rebels obtained possession of the town, having our hospitals in their hands, and taking a great many of our men prisoners.”[iv]

Throughout July 2, the regiment moved to different positions and sheltered from enemy sharpshooters, but did not directly engagement on a battle line. On July 3, they came under fire during the great cannonade and several of their soldiers were wounded.

When did Lieutenant Whitney get wounded? Where was his injury? The accounts reference thus far in research for this post do not specify. There is a higher percentage of chance that he was wounded on July 1 since the majority of the regiment’s casualties went down on that day; though, he may have been wounded by artillery projectile on July 3. If he was wounded on July 1, he may have been transported by ambulance to Christ Lutheran Church in the town of Gettysburg. Other casualties from the regiment had that experience and it was noted in primary sources.[v] If he did end up at the church or one of the nearby homes, Whitney would have been taken prisoner when the Confederates occupied the town; presumably, if he was in Confederate hands, they left him behind. So far, no records suggest that Whitney was a prisoner for a lengthy time, so if he was in a captured hospital, he probably was left behind when the Confederates retreated.

On October 21, 1863, Whitney promoted from lieutenant to captain, suggesting he had recovered from his Gettysburg wound and returned to his unit. He survived the war, married, and worked as a cloth dyer until his death on December 18, 1900.[vi]

With so many unknown and unclear details about Whitney’s experiences at Gettysburg, why spend time piecing his story together and continuing to look for more clues? His photograph portrait is identified and when we look at him, we look into the eyes of a soldier who fought at Gettysburg, was wounded, and survived. This is no romanticized story or fine oil painting. Instead, we look at an individual soldier who fought on Seminary Ridge on the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg. Perhaps there is something powerful about that realization and the reminder that individual soldiers formed the units later represented by red and blue lines on military maps.

**Note: The Ninth New York State Military was the original designation for the unit that later became the 83rd New York.

Sources:

[i] Lawrence M. Whiteny. New York, U.S., Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts, 1861-1900. Accessed through Ancestry.com

[ii] 83rd New York Infantry Regiment, Unit History Summary. https://museum.dmna.ny.gov/unit-history/infantry-1/83rd-infantry-regiment

[iii] Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Volume 27, Part 1. Report No. 54.

[iv] John W. Jacque. Three Years Campaign of the Ninth N.Y.S.M during the Southern Rebellion. (1865). Pages 154-155.

[v] Gregory A. Coco. A Vast Sea of Misery.

[vi] Lawrence M Whitney in the New York, New York, U.S., Index to Death Certificates, 1862-1948. Accessed through Ancestry.com

It is strange that the image shows him wearing the insignia of “crossed cannons” for artillery on his cap. He doesn’t seem to have served in an artillery battery.

Sarah, I love the conclusion to your piece. I sometimes forget there were individuals, and by extension their families etc. who made up those map lines!