Called Out For “The Men Not To Fire” At Chancellorsville

Dark night. A general on a scouting expedition out in front of the lines. Moonlight and dense woods. A call for troops not to fire. What Civil War account comes most quickly to mind? Probably “Stonewall” Jackson at Chancellorsville.

However, according to an excerpt from a lengthy letter written on May 9, 1863, and detailing the Chancellorsville campaign, Jackson was not the only general out in front of his lines on the night of May 2.

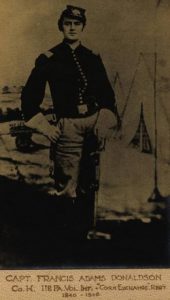

Captain Francis Adams Donaldson of the 118th Pennsylvania Infantry (1st Brigade, 1st Division of the Federal V Corps) was positioned along Mineral Springs Road, northeast of the Bullock House. They covered the routed toward Scott’s Mill and Banks Ford on the Rappahannock River. The 118th had spent the day of May 2 digging earthworks; sounds of battle reached them, and in the moonlit night a Union tragedy of friendly fire could have happened.

Meantime the roar of battle slackened somewhat and at about nine o’clock, I should judge, although I did not note the time, Genl. Howard, with a portion of the 11th Corps which had just been crumbled to pieces by the Confederates, passed through the line at a short distance to the right of our regiment, and they continued to pass for over an hour. They seemed to be in pretty good condition, although not in anything like regular order. They said nothing, but moved silently to the rear. After they had passed there suddenly came a lull in the storm of battle. There was not a sound to disturb the most sensitive ear. Indeed the silence was most oppressive, causing the men, without any instruction to do so, to speak together in whispers.

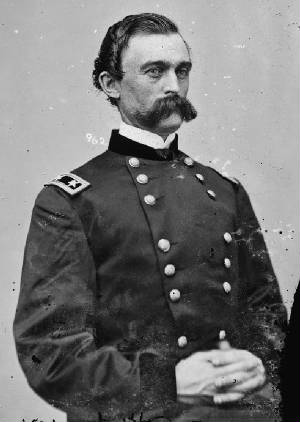

The night was a glorious one, the full moon shining brightly and making objects quite distinct in the surrounding woods. An occasional cloud would now and then obscure it, only to make its rays more brilliant as they again burst forth and illuminated the forest. About this time a slight noise was noticed in our front, and peering eagerly into the woods, we tried to make out what it was. Soon a voice called out for “the men not to fire,” as it was General Griffin, who having been out a short distance to observe the character of the ground was now making his way back again, and as he passed along with but one of his staff with him, I could not but notice how very much better satisfied the men appeared at getting a glimpse of the man, of all men, they had the most confidence in. Indeed, I never before saw such devotion to any single individual as his division to Genl. Griffin, and it was deserved, too, because he is always the friend of the enlisted men and looks closely after their wants.

Charles Griffin, born in 1825, had made the U.S. Army his career since his entrance to West Point in 1843. Graduating twenty-third out of thirty-eight in the Class of 1847, he commissioned into the 2nd U.S. Artillery and saw action at the end of the Mexican-American War and in New Mexico Territory. Griffin returned to West Point to teach artillery and took the academy cannons to battle at First Bull Run in 1861. The following year he promoted to brigadier general and took command of an infantry brigade; he took command of a division in the V Corps prior to the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862. Illness forced him to miss the starting marches of the Gettysburg Campaign, and his return mid-campaign was celebrated by his troops, corroborating the admiration Donaldson wrote about in his Chancellorsville letter.

As has been stated often in reference to “Stonewall” Jackson at Chancellorsville, a scouting mission is not the proper place for a lieutenant general. Neither is it the proper place for a division commander accompanied by one staff officer. However, Griffin got away with his escapade; the voice carried over the sounds of the two horses returning toward the Union line, warning the troops to hold fire. Since no friendly fire erupted along that part of the Union line that hour, the scouting incident goes largely unnoticed in Chancellorsville studies.

However, it’s tempting to wonder what might have happened if the Union soldiers hadn’t got the message or had been more trigger-happy. Would Griffin have fallen to friendly fire? Would the firing have startled other Union troops and provoke volleys toward the east in their front? Drawn artillery fire into empty woods to their front? Pulled attention away from the Confederates to the west? Prevented Jackson from making his fateful ride?

Instead, everything stayed silent. Griffin crossed back into his lines. Further down Bullock Road, a Confederate general rode into the silence and crossed Bullock Road perpendicularly on Mountain Road. That officer in gray and wrapped in a raincoat would become the poster-example of why commanders should not go on scouting expeditions beyond their lines.

Two rides—likely around the same time if Donaldson’s later descriptions of rapid firing to the right of his regiment match the Confederate friendly fire episode which was quickly followed by Federal response. Two different fates for the generals who attempted to scout the ground beyond their troops’ lines.

Sources:

Francis Adams Donaldson, edited by J. Gregory Acken. Inside the Army of the Potomac: The Civil War Experience of Captain Francis Adams Donaldson. (Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 1998).

Frank O’Reilly’s Chancellorsville Battle Map #6, May 2, 1863, 9pm to 11pm.

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Volume 25, Part 1. (Reports)

Great story, Sarah! Hadn’t heard this before. Lot’s of ‘What if’s”! General Griffin has been largely underrated, despite the fact that he seems to show up, and perform well, in many serious battles.

thanks Sarah … i read Acken’s book years ago (my great-great grandfather was in Co. G. of the 118th) … but i didn’t recall this incident … thanks for resurrecting this episode about a great, if not somewhat foolhardy, General Officer … the rest of book is quite good as well.

“As has been stated often in reference to “Stonewall” Jackson at Chancellorsville, a scouting mission is not the proper place for a lieutenant general. Neither is it the proper place for a division commander accompanied by one staff officer. However, Griffin got away with his escapade;”

Add division commander General Kearny to the list, although he was lost at an earlier battle. Scouting in front of his troops on a muddy battlefield in a clouded twilight, not believing direct advice that rebs were in his front and dying a warrior’s death. His bravery, as evidenced by his cavalry charge at the Battle of Churubusco (Mexican-American War), predated any influence of McClellan.