Fallen Leaders: Admiral Andrew H. Foote – Another Farragut?

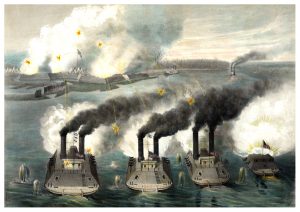

February 6, 1862, midday: Advance cavalry elements of Brig. Gen. U. S. Grant’s 17,000-man force broke from the woods fronting the Confederate fort they intended to attack and were startled to observe the Stars and Stripes flying from the flagpole. Several Union ironclads and gunboats lay quietly in the Tennessee River below the ramparts. Big guns in the fort and on the water that had been thundering for the last couple hours were silent.

The troopers entered warily to find two U. S. Navy officers and a gaggle of sailors guarding Rebel prisoners and awaiting the army. Fort Henry’s commander, Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman, was aboard the ironclad USS Essex surrendering to Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote. General Grant arrived an hour later and took formal possession.

Foote would lead the Western Gunboat Flotilla to more victories. The next summer, he would be appointed to one of the navy’s most prestigious commands, the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, as it prepared to campaign against Charleston. But suddenly, one of the navy’s best leaders fell ill and died of inflamed kidneys, stress, and the lingering effects of a wound. “He would have gained laurels like those so gallantly won by [David G.] Farragut,” wrote a contemporary.[1]

Andrew Hull Foote was born in 1806 at New Haven, Connecticut, the son of a wealthy West India trader and later U. S. Representative, Senator, and Governor. In 1822, he became a midshipman in the United States Navy and sailed the seas for forty years—the Caribbean, North and South Atlantic, Mediterranean, Pacific—advancing to lieutenant, then commander.

From 1849 to 1851, Foote commanded USS Perry cruising the African coast, suppressing the illegal slave trade. He captained USS Portsmouth of the East India Squadron in 1856 observing British operations against Canton during the Second Opium War. When Chinese shore batteries fired on the ship, he led a landing party, seized forts along the Pearl River for insulting the flag, and briefly occupied Chinese territory.

This experienced seaman was a staunch Christian and ardent social reformer who organized temperance societies aboard the ships; his vocal advocation for abolishing the grog ration succeeded in 1862 when Congress prohibited alcohol afloat. On shore, Foote was a popular speaker in the lecture circuit, espousing temperance, improved conditions for sailors, overseas missionaries, abolition, and African colonization for former enslaved.

In a popular 1854 book, the commander described Africa’s geography and customs, condemned the evil trade, and demanded protection for American citizens and commerce abroad. He heaped contempt on those who profited from human misery. One day they would have to answer to God, he wrote, for “the theft of living men, the foulness and corruption of the steaming slave-deck, and the charnel-house of wretchedness and despair.”[2]

By summer 1861, Foote was promoted to captain, then to flag officer (equivalent to brigadier general) and sent west to assume the undefined role of supervising the army’s brown-water navy. The Western Gunboat Flotilla, an ad hoc, unprecedented joint-service organization consisted of hastily designed and constructed ironclads, commercial river steamers indifferently strengthened for big guns, and a fleet of riverboat transports.

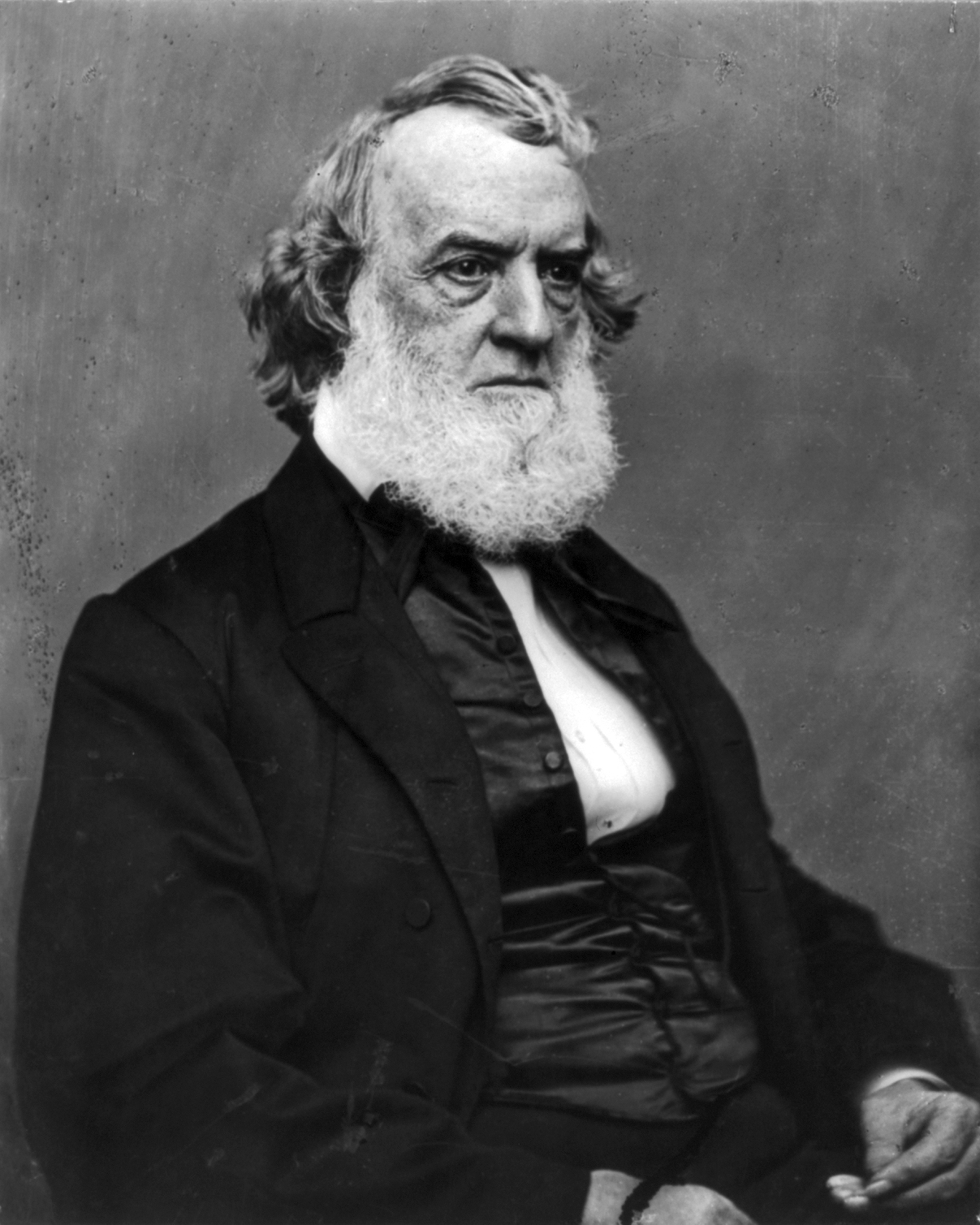

Navy Secretary Gideon Welles was focused on the immense warship procurement program for an almost impossible continent-wide blockade; for the river flotilla, he agreed only to provide some naval artillery along with a few officers and senior sailors.

The army was on its own in the hinterland to build, convert, supply, man, and operate warcraft. Rivers were not the navy’s business; the army was in complete command. Foote, the deep-water sailor, had no river experience and no shallow-water tactics. River craft were unlike anything he and his officers had managed.

The expanding flotilla was an orphan organization foreign to all existing command and logistical procedures in both services. Maj. Gen. John C. Freemont directed the Department of the West, but he could not provide adequately for his own soldiers and felt no obligation to pay a bunch of raw sailors. Foot’s urgent requirements for shot and shell became mired between service bureaucracies. President Lincoln fired General Freemont in November 1861, assigning Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck in his place.

In January 1862, Grant and Foote convinced Halleck to move against Forts Henry on the Tennessee River and Donelson on the Cumberland. These were vulnerable positions in middle Tennessee crucial to the thin Confederate defensive line stretching from Arkansas to the Cumberland Gap. The soldier and sailor formed a potent team even though there were no formal command structures or procedures for joint operations; no soldier could issue orders to a sailor or visa-versa.

Foot’s biographer: “As individuals, Foote and Grant could hardly have been more different. One was a God-fearing abolitionist teetotaler; the other may have feared God, but he was certainly indifferent toward slavery and hardly abstemious. Yet they worked together splendidly.” The successful river campaign would owe much to their combined leadership, initiative, and lack of ego. Foote grasped the necessity for close cooperation, telling his brother that the services were “like blades of shears—united, invincible; separated, almost useless.”[3]

Fort Henry was an easier conquest than it should have been, falling quickly to the gunboats while Grant’s men were miles away mired in mud. It was poorly sited, poorly designed, undermanned, and lightly armed. Foote was gratified but concerned. Most Rebel rounds bounced off the ironclads, but a 32-pound shot penetrated the armor on Essex, hit a boiler, and blew scalding steam through the ship causing 32 casualties.

“I never again will go out and fight half prepared,” he wrote his wife. “Men were not exercised [trained] & perfectly green. The rifle shots hissed like snakes. Tilghman, well he would have cut us all to pieces had his best rifle not burst & his 128-pounder been stopped in the vent.”[4]

Foote sent three wooden gunboats—which were undamaged, faster, and more maneuverable than ironclads—on up the Tennessee. They destroyed the Memphis-to-Louisville Railroad bridge, cutting communications between Rebel field armies forcing them to withdraw. Cheered by Unionists along the banks, they captured and destroyed nine Rebel vessels, including an ironclad under construction, and took hundreds of tons of supplies. The raid reached as far as Muscle Shoals, Alabama, the river’s navigable limit.

Grant pursued fleeing Rebels 12 miles overland to Fort Donelson while Foot sent his boats up the Cumberland to approach from the water. A much harder nut to crack, the fort mounted powerful batteries on 100-foot bluffs served plunging fire on the river below. Foote was reluctant to attack without thorough reconnaissance while an anxious Grant urged him to advance.

The flotilla engaged on February 14. The ironclads were pummeled, forced to withdraw with heavy damage and many casualties. A shell fragment wounded the flag officer in the foot. His boats still controlled the river but were out of the fight. “Unconditional Surrender” Grant battered the Rebels into capitulation, bagging an entire field army and beginning his rise to supreme command. Confederates abandoned Kentucky and most of middle Tennessee.

Unlike General McClellan’s failure on the Peninsula that spring, Forts Henry and Donelson ranked among the deadliest Union strokes of the war. Waterborne mobility and firepower were decisive factors; the Western Gunboat Flotilla was no longer an orphan. Secretary Welles saw it as a navy asset while Secretary of War Stanton and General Halleck became supportive.

However, lack of protocols, continued disagreements, and disconnects between Halleck, Welles, and Foote forced the commander in chief himself to serve as joint field commander. From the White House, Lincoln issued instructions down to the movements of individual ships and ordering of guns and supplies. The frustrated flag officer would have preferred to operate independently of the army, subject only to orders of his secretary and president just as the navy worked at sea.

The flotilla proceeded down the Big Muddy and connected with Brig. Gen. John Pope and his Army of the Mississippi for the next objective. Island No. 10 was a formidable obstacle on an enlarged sandbar at the bottom of a dangerous horseshoe bend with 7,000 Rebels and five batteries mounting 24 guns.

The flag officer was hesitant to expose his not-fully-repaired ironclads. On the north-flowing Tennessee and Cumberland rivers, incapacitated boats floated back to safety in Union lines whereas the swift Mississippi would push them right down into enemy clutches to become a threat to all Northern river cities. Significant steam power was required just to hold position in the current. His wound was not healing; he was in pain, on crutches, and his son had just died.

Foote brought up 11 rafts mounting 13-inch mortars and on March 15, 1862, began a furious three-week bombardment from long range that achieved no results against sand and log ramparts. An impatient General Pope—sitting across the river in New Madrid, Missouri—pushed the flag officer to run a gunboat past the batteries and cover the army’s crossing to the Tennessee side below and behind Rebel positions on Island No. 10.

Captain Henry Walke of the ironclad USS Carondelet persuaded Foote that he could make it. On the moonless night of April 4 under a raging thunderstorm, Carondelet slithered downstream unscathed and almost undetected. Another ironclad followed. Pope’s army crossed over, isolated the Rebel garrison, and forced their capitulation on April 8 just as the Battle of Shiloh was raging and McClellan was bogged down on the Peninsula. The river was open as far as Memphis.

Carondelet’s dramatic passage introduced a new naval tactic, unthinkable through centuries of fragile wood and fickle canvas: driving war vessels through narrow channels past heavily armed fortifications. Steam, iron, and heavier naval artillery had evened the odds between ship and shore. These methods would be replicated at New Orleans, Vicksburg, Port Hudson, and Mobile Bay.

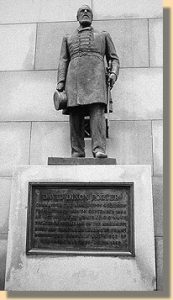

Badly in need of rest and recuperation, Foote was relieved in May, 1862. Later that year, Congress created the rank of rear admiral; Foote was among the nation’s first along with David G. Farragut and David D. Porter. The army’s Western Gunboat Flotilla was transferred to navy command and re-designated the Mississippi River Squadron. Under Admiral Porter, the boats teamed up with General Grant against Vicksburg and conquered the mighty Mississippi.

The country was shocked by Foot’s death in New York City on June 26, 1863. Secretary Welles was devastated; they had been school chums at the Connecticut Cheshire Academy forty years before. “The river naval service is unique,” he confided to his diary. “Foote performed wonders and dissipated many prejudices. The army has fallen in love with the gunboats and wants them in every creek. . . .

“His death will be a great loss to the country, a greater one in this emergency to me than to any other out of his own family. . . . In later and recent years we have mutually sustained each other. I need him and the prestige of his name in the place to which he has been ordered.”[5]

Admiral Samuel F. DuPont commanded the attack on Charleston Harbor by 9 ironclads, April 7, 1863, to spectacular failure with several badly damaged and one sunk. This was due less to incompetence by DuPont than to unrealistic expectations by Welles and others concerning the effectiveness of little ironclad monitors against stout fortifications and hundreds of guns.

DuPont foresaw the outcome but hesitated to boldly confront determined superiors on the ironclads’ vulnerabilities. One might speculate that Foote, once he surveyed the situation, and given his closeness with Welles and frank nature, could have avoided the debacle.

DuPont counted Foote a friend also, calling him “earnest, persevering, indomitable, with the best puritan attributes—a sort of Northern Stonewall Jackson, without his intellect and judgment, but altogether a splendid Navy officer.”[6]

Three U. S. Navy warships have been named for Foote, as was the Civil War Fort Foote on the Potomac, now a National Park, and Foote Street NE (and Foote Place) in Washington, DC.

While Andrew Hull Foote is remembered for his services in China and the Civil War, the assignment of which he was most proud was command of the brig Perry in helping to halt the African slave trade.

[1] James B. Eads, “Recollections Of Foote and The Gun-Boats” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Being for The Most Part Contributions by Union and Confederate Officers. Based Upon “The Century War Series.” Edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, of the Editorial Staff of “The Century Magazine,” 4 vols. (New York, 1884-1888), vol. 1, 346.

[2] Spencer C. Tucker, “Lieutenant Andrew H. Foote and the African Slave Trade,” in Walter J. Boyne, Today’s Best Military Writing: The Finest Articles on The Past, Present, And Future of The U.S. Military (New York: Tom Doherty Associates, 2004), Kindle Edition, 41.

[3] Spencer C. Tucker, Andrew Foote: Civil War Admiral on Western Waters (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2000), 134.

[4] Ibid., 152.

[5] Edgar Thaddeus Welles, ed., Diary of Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy under Lincoln and Johnson, 3 vols. (Boston; New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1911), vol. 1, 167, 335-336.

[6] Tucker, Andrew Foote, 152.

Great article about an often overlooked leader. It would have been a great talk for the Fallen Leader Symposium. One small error…the Tennessee River does not go near Nashville, the Cumberland River does.

Thanks Charles for that correction, and the kind words. Change made.

Thanks for this excellent article.

Although U.S. Grant is generally regarded as the hero of Forts Henry and Donelson, the article makes clear the former was entirely a Navy victory.

Foote, Walke, Porter and Grant all showed a genius for improvisation and inter-service cooperation that had Albert Sidney Johnston backing up to southern Tennessee for his surprise attack at Shiloh. Even there Union gunboats Tyler and Lexington played a key role lobbing shells into rebel lines all night as Grant rallied his troops to victory with reinforcements from Buell.

The magnificent Navy-Army cooperation continued throughout the Vicksburg campaign. Neither, alone, could have succeeded in winning the war in the west.

Thank you! Tyler and Lexington rarely receive recognition for their critical support at the stand by the river.

Excellent tribute. He’s very much like C.F. Smith – powerful prewar service and early Civil War service cut short and left with unfinished chapters.

Rising 202 feet, the tallest monument at Vicksburg NMP is the Navy Memorial, at the base of which stand four statues: Farragut, Porter, Davis and Foote. The above excellent article presents a solid summary of the achievements of Andrew Hull Foote; and hopefully readers are inspired to dig further into the career of this remarkable man. “The Life of Andrew Hull Foote” published 1874 (James Mason Hoppin) is another excellent resource, available online: https://archive.org/details/lifeofandrewhull00hopprich/page/n8/mode/1up