“Too trivial for big history:” One Yankee Private and Three Accounts of Second Bull Run

ECW welcomes back Douglas Ullman, Jr.

Martin Alonzo Haynes was 20 years old when he and approximately 2,000 men under Union Brig. Gen. Cuvier Grover charged the unfinished spur of the Manassas Gap Railroad on the afternoon of August 29, 1862. Grover’s five-regiment brigade achieved one of the promising Federal breakthroughs of the Second Battle of Bull Run. Haynes and his comrades surprised the rebels with a bayonet charge that drove the southerners out of what many believed to be a ready-made earthwork. The fighting was remorseless: hand-to-hand and man-to-man. However, after a short while, it was clear that Grover’s Yankees were not going to receive any support. Meanwhile, Confederates from three brigades of A.P. Hill’s division struck the exposed Federals on three sides and pursued them south of the railroad cut. Grover’s assault was essentially the Union dilemma at Second Manassas in miniature: brutal fighting that, though initially successful, was ultimately unsupported and resulted in little more than the death or wounding of the brave individuals who made the charge. In the span of 20 minutes, Grover’s five regiments lost 486 men killed, wounded, or missing (OR, Vol. XII, Part 2, pp. 439).

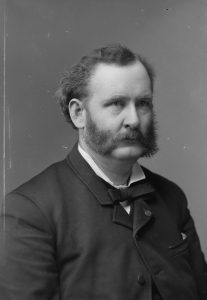

Haynes survived the charge, the war, and two decades later served two terms in the U.S. House of Representatives. More importantly for students of the war, Haynes was also the historian for his regiment, the 2ndNew Hampshire. In 1865 he published “a ‘free-hand sketch’” of the regiment’s service, “dashed off while the events narrated were still as but the doings of yesterday in mind and memory.” Thirty-one years later, he penned A History of the Second Regiment New Hampshire Volunteers, which was essentially an updated version of the earlier narrative, augmented with additional details and anecdotes from the regiment. This second work has been cited in several books by numerous historians and passages have been included on interpretive signs at Manassas National Battlefield, including recently revised signs at the site of Grover’s Attack on the Unfinished Railroad. As if that were not enough, Haynes published a compilation of obituaries for his comrades who died in the two decades after the printing of the 1896 regimental history. In other words, Martin Haynes was the authority on the 2nd New Hampshire Volunteers in the American Civil War.

While working on his 1896 book, Haynes consulted a trove of more than 150 letters he wrote to his future bride, Cornelia T. Lane. They “were carefully copied” and “then given to the flames”—a sad development for future historians. Years later, the old veteran reopened the manuscript of his wartime correspondence and “read with indescribable interest [his] own story of more than a half century ago.” He published 60 copies of the collection “especially for members of the family” under the title A Minor War History Compiled from A Soldier Boy’s Letters to “the Girl I Left Behind Me.” This was not a complete collection of his correspondence with Cornelia, for he omitted those letters that contained “strictly personal matters as concerned only the two of us.” His letters, he admitted, did “not deal, like Sherman’s letters, in the grand strategy of campaigns.” Instead, he hoped to share “the trivialities of army life…the small talk of camp, and many incidents that are too trivial for big history, but are really interesting and worth saving” (Martin A. Haynes, A Minor War History, introduction).

Far from being trivial, Haynes’s letters reveal a grunt’s-eye-view of combat. This is especially true of the letter he wrote to Cornelia on September 6, 1862, in which he recounted the charge of Grover’s brigade at Second Bull Run. After providing a brief summary of his movements from Alexandria to Manassas, Haynes proclaimed, “[o]ur brigade here [at Bull Run] showed its mettle as it never had before, especially the Second Regiment.” In the subsequent narrative, tactical details are scarce. He did not relate anything about the orders which carried him into battle, nor that the 2nd New Hampshire was in the center of Grover’s attacking column—information that appears in both versions of his regimental history. Instead, he narrowly focused on his own experience and that of the men around him. Haynes “advanced through woods, without any supports,” and came upon the Confederates taking cover “behind a railroad grade five or six feet high.” The ensuing fight “was savage work for a short time,” he told Cornelia, “but we were determined to drive them, and we did (Haynes, A Minor War History, pp. 66-67).

The clash between Grover’s brigade and the Confederates in the railroad cut was fierce and personal—“the most brutal kind of fighting,” according to John Hennessy. In 1896 Haynes described a scene in which rebels “who made a fight were instantly shot or bayonetted” by New Hampshiremen “wild with the rage of battle.” As the fighting progressed, the impetuous Granite Staters encountered a second line of Confederates, a struggle recounted with remarkable frankness in 1865. “The dull ‘thug’ of the bayonets as they were buried in quivering flesh, the sharp crack of rifles and revolvers, the whistle of bullets, the fierce shouts of hatred and the moans of the wounded, ascended together from that scene of deadly conflict.” None of this language appeared in his letter to Cornelia. There, the fight for the second line was boiled down to a single sentence. “Then we went for the second line, a few rods further on, and set them agoing.” A remarkable understatement compared to the graphic violence recounted in 1865. The 2nd—which was in the center of Grover’s brigade—eventually outran its supports “[a]nd pretty soon it became apparent that what there was left of us were being surrounded.” Writing to Cornelia, Haynes confessed he and his surviving comrades started to escape—“we had to or be taken prisoners” (Hennessy, John, Return to Bull Run, pp. 257; Haynes, A Minor War History, pp. 66-67).

While young Martin spared Cornelia some of the more gruesome details in 1862, he did share some frank personal anecdotes that did not appear in either of his regimental histories, including his own violent encounter with a Confederate. “I got my first man as I went over the [railroad] bank,” he wrote. “I dashed round a big bush in the very edge of the grade right onto a rebel, who threw his gun up aiming at somebody on my right. He never fired, for I gave it to him from the hip and doubtless saved the life of some Second Regiment man—I’ll never know who.” During the retreat, he felt a bullet graze his “upper lip and the roots of my nose, and for a while I was doing the ensanguined act on the smallest capital of any man in the regiment. It was a pretty close shave all the same.” With a young man’s bravado, he proclaimed “[o]ne inch further, in the wrong direction, would have spoiled my beauty, and three inches would have spoiled me” (Haynes, A Minor War History, pp. 66-67).

Others were less fortunate. By Haynes’s count, the 2nd New Hampshire “lost 147 men out of a little over 300 that went in, and most of these within a very few minutes.” Many others had not returned following the charge. “The actual fate of a lots[sic] of the boys is still in doubt.” Sadly, what was “still in doubt” in 1862, was considered settled fact by the war’s end. As regimental historian, Haynes provided personal details about some of the men who suffered in the charge and, in 1896, even provided photographs. It’s worth pointing out that the individual casualties mentioned in each of his three accounts of Second Bull Run can be corroborated by the Adjutant General’s Report. Whether writing during his service, in 1865, or 1896, Haynes seems to have been a reliable source. (Hennessy, John, Return to Bull Run, pp. 257; Haynes, A Minor War History, pp. 66-67; Haynes, A History of the Second Regiment New Hampshire Volunteers (1896), pp. 128-138; for a more detailed accounting of the losses of the Company I, 2nd New Hampshire, see Report of the Adjutant General with Compliments of Natt Head, Adjutant General and Quartermaster, State of New Hampshire, Year Ending May 20, 1865, pp, 93-94).

On their own, each of Haynes’s three accounts of Grover’s Attack is a fine source that helps illuminate the brutal struggle of August 29, 1862. Indeed, historians would be lucky to find one such source for many Civil War regiments. Taken together, however, Haynes’s writings weave a wonderful and nuanced tapestry of personal and corporate experience that place the individual soldier into the broader context of the battle and the war. The regimental histories provide great insight into the service of the regiment while Haynes’s letters provide personal stories that he later omitted from the broader narrative. In combination, these sources afford us a much richer understanding not only of battles like Second Bull Run, but of the conflict as a whole. Three books by the same man on the same subject may seem like overkill, vanity, or both. But in the case of Martin Haynes of the 2nd New Hampshire, it is a gift to historians and anyone who wishes to understand the American Civil War.

Thank you kindly for this excellent article! It led me to re-read the portion of Hennessy’s book on Grover’s attack and to plan a visit there as well.

Thank you, as General Cuvier Grover is my 5th great-granduncle