Stealing Books during the Battle of Fredericksburg

The destruction and plundering of Fredericksburg are legendary and marked a new era of military and civilian interactions during the American Civil War. On December 11, 1862, Union soldiers battled their way into the small city on the banks of the Rappahannock River. In the dark morning hours, Federal engineers had begun sliding the pontoons into the river and laying the planks to construct the floating bridges. On the Fredericksburg side of the river, Confederate soldiers from William Barksdale’s brigade waited, allowing their opponents to make progress before opening fire. Sharpshooter tactics slowed and then halted the bridge construction, leading to different actions at the various bridging points.

A Union artillery barrage opened on the civilian town in a futile attempt to clear out the pesky sharpshooters. Ultimately, the cannon-blasted buildings and rubble gave the sharpshooters more cover to continue their deadly work, and when the bombardment ended, Barksdale’s men still held the town. By the afternoon, Union infantry volunteered to pole across the river in small boats and battle for bridgeheads on the Fredericksburg side. Urban warfare erupted, but by dark, Barksdale had pulled his regiments out of the city, abandoning the houses, stores, warehouses, churches, and public buildings to the advancing Union soldiers.

Organized plunder began and for a while, officers turned a blind eye or actively participated. Some soldiers prowled for food or other necessities. Others sought alcohol or luxury items. The joys of destruction beguiled the hours in Fredericksburg, leaving behind a trail of smashed glass, broken furniture, axed pianos, ruined clothing, ripped feather beds, and other scenes that horrified the civilians when they returned and gave some credence to their ideas of “Yankee vandals.”

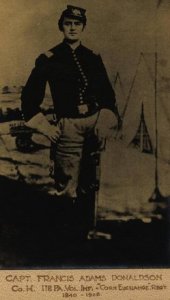

Among the interesting accounts of this destruction, two Union officers — Henry L. Abbott of the 20th Massachusetts Regiment and Francis Adams Donaldson of the 118th Pennsylvania Regiment — left details of their personal plundering in Fredericksburg.

On December 21, 1862 — ten days after the crossing at Fredericksburg — Henry Abbott wrote to his sister Carry from his camp in Falmouth, Virginia. Angry about the Union’s defeat at Fredericksburg, he poured out his frustration and then turned to “lighter topics.”

I tried to get you some memento of Fredericksburg, but got nothing better than a commonplace edition of Byron. I have got a very good edition of Plutarch’s Lives for the governor. I did get a most beautiful writing desk but it was taken away from my servant. I have two children’s books for Frank & Arthur. I went into nearly every house to get some nice little silver thing for mamma & Mary Welch, but was too late. Macy got just the thing — a little bed lamp of solid silver….[i]

Acting major for the 20th Massachusetts on December 11, 1862, Abbott led approximately 60 men into the street fighting near the upper crossing at Fredericksburg. As one of the early regiments to cross the river at this location, the 20th fought street by street, through exposed intersections as they pushed their Mississippi enemies out. By the end of that day, Abbott had lost nearly half the men under his immediate command. Perhaps that evening or maybe later in the following days, he went on his exploration for mementos, probably wandering into houses or buildings that still stand in downtown Fredericksburg today.

Abbott admitted to his sister that he was looking for specific items, particularly silver to take home to his family. His attitude in the letter suggests he felt nothing wrong with entering the empty houses and taking possessions of Southern civilians who had fled town. Since he couldn’t find silver or other nice things, he resorted to stealing books, a rather heavy addition to his belongings. He did not offer details if he felt any remorse or considering in writing any justifications for his actions. He wanted something. The houses were empty, and he went inside.

Captain Francis A. Donaldson crossed into Fredericksburg on December 13 and witnessed the scene after two days of plundering, writing to his aunt:

The sight that now met our eye was a very remarkable one, indeed. The city had been thoroughly sacked. The household furniture of the whole place lay in the streets. In every direction could be seen men cooking coffee on a fire made from fragments of broken furniture and I actually saw horses feeding out of a piano, the instrument part of which had been broken out to make a feed box of the body. Books and battered pictures lined the streets, bureaus, lounges, feather beds, clocks and every conceivable thing in the way of furniture lay scattered on every side. The destruction was appalling and most wanton, even if justified by the usage of war.[ii]

Though shocked by the scene, Donaldson admitted that when his regiment halted, he entered a nearby house to look around. Perhaps the sight of cannonball destruction through the dwelling influenced his thought process. He described entering the home’s library and seeing bricks, mortar, and books already strewn on the floor. Here, Donaldson “took from the collection a nicely bound volume of Waverly (Ivanhoe) intending to retain it as a souvenir.”[iii]

In his private letter Donaldson displayed more guilt than Abbott, saying, “Thus you see that even I, a commissioned officer, was guilty of vandalism, but I justified myself in this theft by believing the city would, certainly, be destroyed by fire before we got through with it. However, I did not long enjoy the possession of the book as I lost it shortly after in the desperate charge we made up Marye’s Heights.”[iv]

Abbott and Donaldson’s thefts probably happened at different ends of town, based on their river crossing locations and likely on different days. However, they both took books. In contrast to Abbott, Donaldson offered a justification for his plundering and even admitted that he knew it was wrong, but…if the town was going to get destroyed, why not take something?

The idea of taking something as a souvenir is a common thread in these two officers’ writings, and it is interesting to ponder that attitude and thought process. Could the sight of the already-bombarded town have lessened their conviction and moral compass? Both had been in the volunteer army for relatively the same about of time (a few months over a year) and fought in a similar number of battles. Had these experiences lessened their sympathy for civilians who had fled from the now-empty houses? Both were devoted to their families; could the distance, homesickness, and approach of Christmas urged them to find something to send home? As Dr. James Robertson said, “If you don’t understand the emotion of war, you’ll never understand the war.[v]

In the end, their words are the only solid proof (and lack of evidence) left to study. However, it may be helpful to consider the greater context of individual lives, the setting, and the military scene when thinking back on the destruction of Fredericksburg. Not as a justification, but as an attempt to understand the whys behind the facts.

Sources:

[i] Henry Abbott. Edited by Robert Garth Scott. Fallen Leaves: The Civil War Letters of Major Henry Livermore Abbott. (Kent: The Kent State University Press, 1991.) Pages 155-156

[ii] Francis Adams Donaldson, edited by J. Gregory Acken. Inside the Army of the Potomac: The Civil War Experience of Captain Francis Adams Donaldson. (Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 1998). Page 180.

[iii] Ibid, Page 180.

[iv] Ibid, Page 182.

[v] https://vtx.vt.edu/articles/2019/11/clahs-james-bud-robertson-memorial.html

This was just the hors d’oeuvre portion of the later meals to come. All, of course, justified under the easy rubrics of “Hard War” or “proportionate response”. When you dehumanize or demonize your opponent, a little housecleaning seems good for the soul

All justified in war. War is hell, which is why we ought not to have them. The rebels burned the town of Chambersburg, for goodness sake.

This is just 10% of what the Federals did in Georgia, upstate Louisiana and elsewhere. But, before we get too judgmental, it seems to be an ethnic trait of the US military to seek “souvenirs” of one’s war. In Iraq and Afghanistan, we had strict rules about that sort of thing. Yet, there were many efforts made by many soldiers to send home some souvenirs of some sort. Sometimes, the line between finding an item in the street or inside a house can be fine indeed. There was the McHatton cask of china procured by Federal Gen. Lawlor in middle Louisiana. The good general sent it home to his family, while Eliza McHatton tried to find the missing cask, not knowing the General had somehow come to possess the china.

Tom

” It is well that war is so terrible, otherwise we should grow too fond of it. ” Famously said later in that battle. Apparently, Fredericksburg wasn’t terrible enough.