Dranesville: Who Were They?

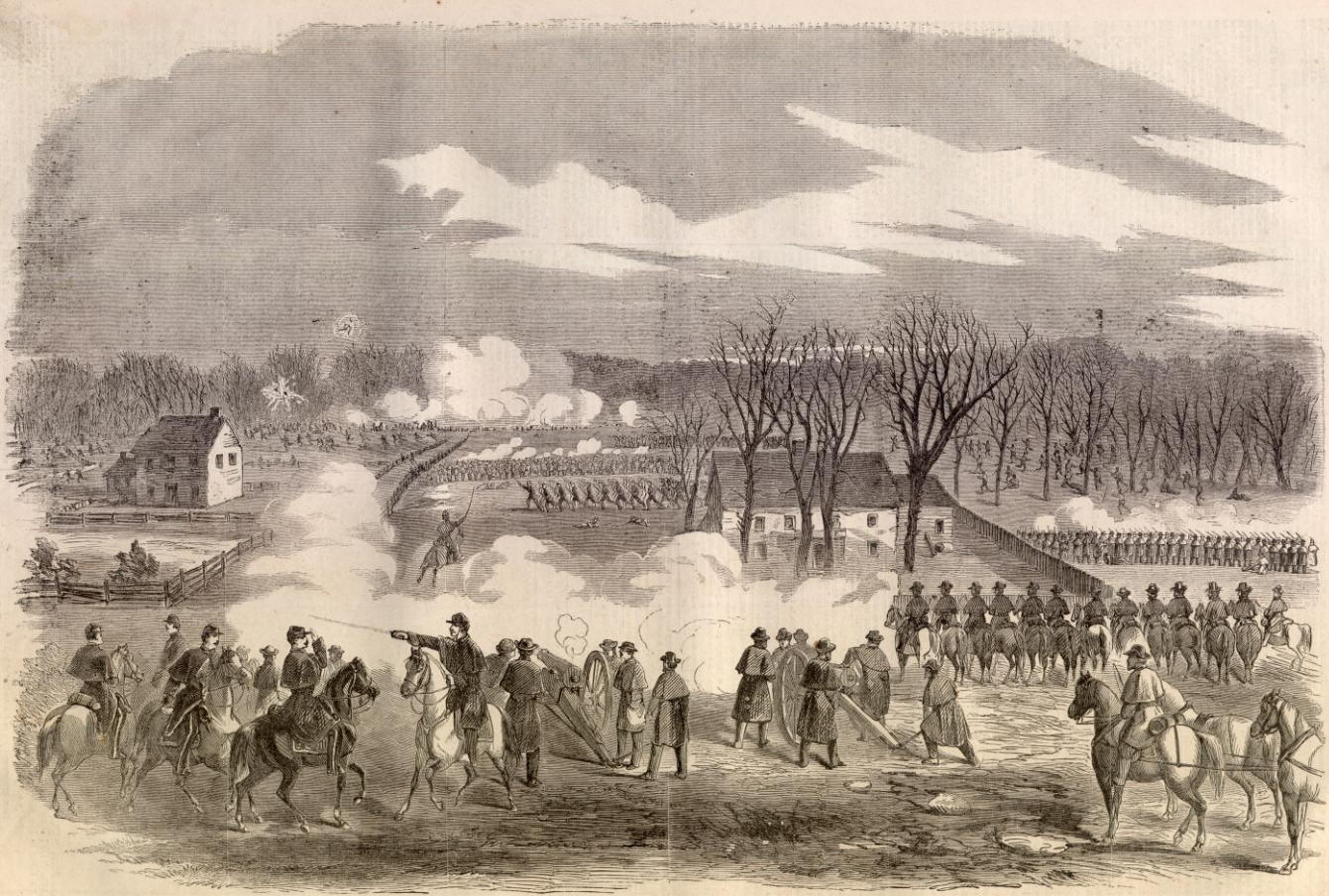

Today is the 160th anniversary of the battle of Dranesville. Every year, the Dranesville Church of the Brethren hosts a peace service to commemorate the battle and remember those who died. I have written about their service before, and this year, the church was kind enough to extend an invitation for me to say a few words. Copied here are my remarks.

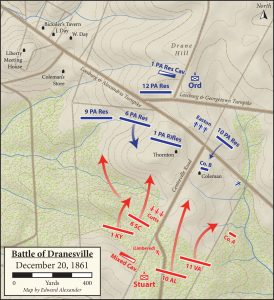

Through the incredible work and research of many people, we know who died at Dranesville on December 20, 1861. Seventy-five soldiers—10 U.S. and 65 Confederates—received wounds that ended their lives. In past years, some identities eluded us—names “only known to God,” but no longer. We know who they were.

Or rather, we know their names. But do we know them? What were their stories? What did they look like? What happened to their families after? While we cannot answer all those questions, we can try to fill in some of the gaps. We know that the average age of the soldier killed here was 24 years old. William Van Dyke, of the 6th Pennsylvania Reserves, was the oldest, at 40 years old. The war was not through with the Van Dyke family though; his son was killed two and a half years later at Spotsylvania Court House. At the opposite age spectrum, Washington Williams from the Sumter Artillery died at the age of 16, and neither Thornwell Brownlee nor Frank English made it to their 18th birthdays.

Frank English didn’t even want to be a soldier anymore. The young boy from Columbia, South Carolina, had enlisted in April 1861, part of the first wave of volunteers who raced off to war expecting grand adventure and excitement. By the winter, though, reality had set in; the monotony of camp life and the daily sicknesses that plagued every Civil War soldier. Frank wrote on Dec. 3, 1861: “If Father will write to Richmond & have me discharged I will come [home] immediately as I would like to be home about Christmas.” In another letter, Frank expressed a desire to resume his school studies. In his last letter home, Frank ended with “I will write you again tomorrow.” But he never had the chance; he was shot in the chest and died within moments.

Not far from where Frank died, the battle meanwhile claimed one pair of brothers—Obadiah and Thomas Harden; Obadiah lingered two days past his 34th birthday, dying on New Year’s Day, 1862. Thomas was killed instantly.

Alexander B. Smith, 21 years old, came from one of the wealthiest families in Pittsburgh, and had barely made it to the recruitment depot before the 9th Pennsylvania Reserves set off for Virginia. On December 20, he stood not far from here, trading some corn beef for salt pork and sharing a smoke with a comrade before he was ordered forward on the skirmish line. He became one of the battle’s first casualties and died on January 14, 1862. He’s buried in the family plot back in Pittsburgh.

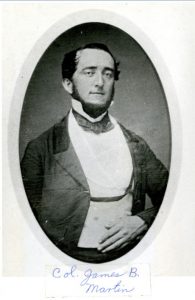

The highest-ranking officer killed didn’t even have to be here. Lt. Col. James B. Martin had received a leave of absence to go back to Alabama but refused to leave on the verge of his regiment seeing its first battle. On the morning of December 20, he told a friend he thought his last day on Earth had come, and that he was “prepared for it.” He was killed near where the firehouse sits now. Getting word of the battle, an Alabama newspaper wrote, “Christmas week has been a sad week in this part of the State.”

Some families got their loved ones’ letters, or, if they were lucky, their bodies, to bury them with proper rites. Others, though got little. John Barbee’s family were forwarded his personal effects consisting of “clothing, blankets, & 1 Bible.” Still others got nothing at all except the notice that their loved one was never coming home.

This quick overview of just some of the soldiers killed here is by no ways exhaustive. There is still so much we don’t know about the individuals killed here. The small action was quickly eclipsed by bigger and bloodier battles that dwarfed the numbers engaged here. But those who died here were remembered by their families and friends for the rest of their lives. Twenty-three years after George Cook died at Dranesville, his surviving comrades named their local veterans’ chapter after him. Forty-eight years after the battle James Coleman made the long trek from Alabama to visit the cemetery in Bristow to see where his brother Sidney was buried after his death here. Though small in scale, the battle of Dranesville reverberated throughout the country—to Pennsylvania and Virginia; the Carolinas and Kentucky; Alabama and Georgia. The fight here that lasted but two hours left echoes and ripples in memory that extended long after. Ripples that in fact bring us to tonight, on the eve of the 160th anniversary of the battle. Those who died at Dranesville were not forgotten in their own time, and because of the efforts made here each and every year, they will not be forgotten in this time, either.

Well done.

Great talk, and always moving to drill down on the individuals involved. Do you know of any consolidated list of Union personnel captured at the battle?

Hi Jeffrey, thanks for the comment. There were no Union soldiers captured at the battle. Federal casualties amounted to 10 killed and 63 wounded. Confederate casualties totaled 200.

Thought I knew a lot about the Civil War, but never heard of this battle. Thanks for an excellent article.

Private George S. Lytton 10th Alabama

19 years old Killed December 20, 1861