An Early War Skirmish on Virginia’s Eastern Shore: The Engagement at Wishart Point

Over the past five years my family has enjoyed several trips to Chincoteague Island on Virginia’s Eastern Shore. From the unspoiled beaches on Assateague to the terrific beer at Black Narrows Brewing, and the oysters, people, the oysters! It’s a terrific, laid-back beach vacation spot where I look forward to returning each year.

Beyond the beaches, brews, and bivalves the Eastern Shore has some terrific Civil War history. While Accomack and Northampton counties both voted in favor of secession in the spring of 1861, a strong Unionist sentiment pervaded several areas of the shore, especially on Virginia’s Atlantic and Chesapeake islands. Both counties sent delegates to be seated at the Wheeling Convention in the spring of 1861, where separation from the mother state was debated. Void of any large-scale battles, the area did see several smaller engagements and frequent troop movement and occupation throughout the Civil War.

Chincoteague Island, on the northern tip of Virginia’s Eastern Shore, was a small fishing and oyster farming community of some 800 residents at the outbreak of the Civil War. With the cosmopolitan popularity of oysters in the mid-19th century, much of the local crop was shipped to New York and Philadelphia, giving the Chincoteaguers a decidedly northern stance. Secessionists from the mainland harassed the loyal islanders in the spring and summer of 1861 and briefly disabled the nearby Assateague lighthouse. It wasn’t long until the rebellion showed up on Chincoteague’s doorstep.

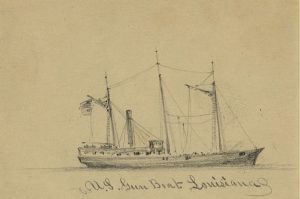

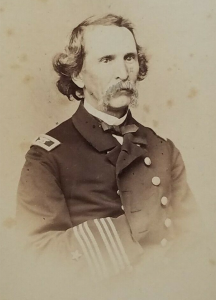

Virginia’s eastern shore, with its many inlets, bays, and coastal waterways, could easily conceal illicit trade and privateering. As the Federal blockade continued to constrict Virginia’s coast, on September 30, 1861, the U.S.S. Louisiana was dispatched from Hampton Roads to Chincoteague Inlet with orders to “closely blockade it and the coast in its vicinity until further orders.”[I] Only a year old, Louisiana was 295-ton iron-hull screw steamer sporting five guns (12, 18, and 32-pounds) and a crew of 85 men. The steamer was under the capable command of Lieutenant Alexander Murray, a native of Pittsburgh and a career naval officer with service in the West Indies, Atlantic, Pacific, and Mediterranean, as well as active service in the Mexican War. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Murray was assigned to U.S.S. Minnesota, but by the summer of 1861 was appointed to command of Louisiana and assigned to the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron at Hampton Roads.

On Louisiana’s arrival at Chincoteague, Murray was apprised of a schooner then being outfitted for privateering in the neighborhood of Wishart Point on the mainland. On the night of October 4, Louisiana captured two sloops while on a reconnaissance into Chincoteague Bay. He determined to make his move on the schooner the following morning.

On the morning of October 5, Murray followed a high tide further into the bay separating Chincoteague and Wallops islands. A series of winding necks and narrows separated Louisiana from Wishart Point by more than a mile. Unable to navigate the narrows, Murray instead dispatched two boats carrying a total of twenty-three men, under the command of Acting Master Hartman K. Furniss and Acting Master Edward Hooker, with instructions to capture the schooner as a prize or to destroy her.

The boats negotiated the narrows and entered the bay, catching sight of the schooner at Wishart Point, as well as two companies of Confederate soldiers stationed nearby. These troops, comprising companies E and H of the 39th Virginia Infantry, had only recently been recruited on Virginia’s eastern shore, and were anxious to test their mettle. When still more than 300 yards from the schooner the Federal sailors came under “a terrible fire” from the Confederates, concealed behind trees and brush, peppering the boats quickly rowing past.[II]

On reaching the schooner the Federals found that it had been partially grounded for recaulking. Realizing they would not be able to free the boat, the men instead boarded, using it as a makeshift breastwork. Several sailors traded gunfire with Confederates while others prepared to set the boat afire. Watching from aboard Louisiana, Lieutenant Murray directed several well-placed shots from his guns, forcing the Virginia companies away from the shoreline. The Federals set fire to the schooner and made the return trip to Louisiana “without further molestation.”[III] On returning to Louisiana it was observed that “the sides of two of the boats were cut by the balls from the enemy.”[IV] In the distance, the would-be privateer burned to the water’s edge.

Both sides involved made unrealistic claims regarding the numbers engaged, the number of casualties, and who was victorious. Lieutenant Murray claimed that the boarding parties were opposed by 300 Confederates, who he believed suffered at least 8 killed and wounded. The Confederates stationed at Wishart Point likely amounted to no more than 75 men and sustained only one casualty, a Private in Company E who suffered a gunshot wound to the thigh. Conversely, the Confederates involved claimed to have “drove the enemy off, killing 20 of them.”[V] Federal losses during the engagement amounted to four men wounded. Of the wounded, Acting Master Hooker was in the most serious condition, having sustained a gunshot to the right breast.

The wound at Wishart Point earned Hooker the distinction of being the first Acting Master wounded during the Civil War. It was also serious enough for Hooker to request a leave from Louisiana to regain his health. The story of his subsequent journey towards that leave is interesting unto itself, and perhaps one we’ll revisit in the future. Hooker was later promoted for gallantry in action and ultimately rose to the rank of Commander by his retirement in 1884.

Two days after the engagement, on October 7, Louisiana captured the schooner S.T. Garrison in Chincoteague Bay, sending her to Baltimore as a prize. By the end of October Louisiana had captured or destroyed nearly a dozen sloops and smaller crafts laden with cord wood, wheat, corn, and sweet potatoes. Murray’s superior, Acting Rear Admiral Louis M. Goldsborough cautioned Murray to “exercise a sound discretion” in seizing smaller craft, as area farmers had long used the local waterways for innocent trade.[VI]

On October 14, Lieutenant Murray visited Chincoteague Island and administered the oath of allegiance to 150 of the more than 800 citizens on the island, acknowledging “many were not apprised of what was transpiring, living in distance parts of the island.”[VII] The citizens appealed to Goldsborough that Murray and Louisiana be allowed to stay at Chincoteague Inlet…

“That by interest and affection we cling to the Union;

That we are united as one man in our abhorrence of the secession heresy;That we have upheld the old flag in spite of many menaces from our secession neighbors;

That the opportune arrival of the war steamer commanded by Captain Murray, whose energetic measures along saved us from subjugation, the enemy having mustered on the opposite shore for that purpose…”[VIII]

While the appeal met with approval to resume their recently restricted oyster trade to Philadelphia and New York, on December 10, 1861, Louisiana was ordered to Baltimore for repairs before proceeding to Hampton Roads.

(B) Approximate location of Louisiana during the engagement of October 5, 1861.

(C) Approximate location of 39th Virginia during the engagement.

(D) Wishart Point, location of the schooner.

While the minor engagement did not dominate the headlines, it did remove any lingering Confederate threat to the loyal islanders at Chincoteague and their oyster trade. Though often inaccurately attributed as the Battle of Cockle Creek, the engagement at Wishart Point marked the only notable fighting at Chincoteague for the duration of the war.

For those of you who visit Chincoteague, while driving across the causeway heading towards the island, carefully steal a glimpse to your right after passing the Queen Sound boat ramp in the distance you might see the area where Louisiana was stationed during the engagement. A short drive down Wisharts Point Road at nearby Atlantic, Virginia, will take you directly to the Point and the area of the engagement. And while you’re on the Eastern Shore be sure to try the oysters…161 years later and they’re still worth fighting over!

**Special thanks to Eastern Shore historian Kellee Blake for ferreting out the facts concerning this small engagement and exposing a fictional 1979 newspaper article that has laid the groundwork for so many inaccurate retellings of this “fantastic story.”**

[I] Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Series I: Vol. 6. 271

[II] ibid, 288

[III] ibid

[IV] Evening Star, Washington DC. October 22, 1861

[V] Record of Events, Company E, 39th Virginia Infantry, November 7, 1861. Fold3

[VI] O.R., 335

[VII] ibid, 337

[VIII] ibid

Would love to connect with you regarding the veracity of “eight small vessels,” “a schooner and two sloops,” the buildup to Federal response, etc., as well as widespread use of incorrect elements from the popular “apocryphal” tale.

I live on Wisharts Point Road and wonder where it got its name. I read in an old issue of Esquire magazine (Smart Money column) over 30 years ago that it was named for a Captain John Wishart of Norfolk who delivered goods to the settlers in the area but have never been ableto find any other referenceto him.