Forts: Pensacola’s Advanced Redoubt

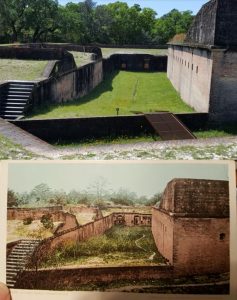

In 2019, I made my first visit to the Pensacola forts (Pickens and Barrancas). This was long overdue, given my proximity. Another fortification that I visited was the Advanced Redoubt, located a short distance north of Fort Barrancas, built to protect the inland approaches to the nearby Navy Yard. Construction on the fort began in 1845, cost $150,000, and was part of the Third System of Coastal Forts following the War of 1812.[1] Its construction is typical for a fortification of the era, including a dry ditch or “kill zone” between the scarp and counterscarp, an underground passageway for access into the counterscarp, apertures for musket fire or cannon placements, and an open parade ground for drilling. Though construction wasn’t complete until 1870, it still experienced activity during the Civil War. Through these events, we can see where Pensacola ranked in importance to the Union war effort along the Gulf Coast.

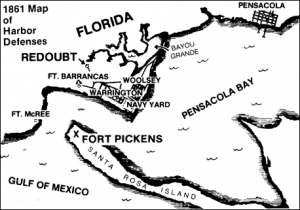

Through 1861 to the spring of 1862, Pensacola was divided. Fort Pickens had remained in Federal hands while Confederates occupied Fort Barrancas, the Navy Yard, and Fort McRee. Numerous skirmishes occurred between the troops, including the Battle of Santa Rosa Island in September of 1861 and an artillery bombardment in November. The Confederate invasion of Tennessee and the progression of Federal forces down the Mississippi warranted the evacuation of 8,000 troops from Pensacola, leaving Colonel Thomas Jones in charge. On May 7, Colonel Jones received news of David Farragut’s fleet anchoring off Mobile Bay and prepared for full evacuation. On May 9, as the final troops were leaving Pensacola, he gave orders to “destroy all camp tents, Forts McRee and Barrancas, as far as possible, the hospital, the [dwelling] houses in the Navy Yard… in fact, everything that could be useful to the enemy.”[2] Per Jones’ orders, the city of Pensacola would remain untouched, though one home became damaged when its neighboring oil factory was burned. The surrender of Pensacola was made official on May 10 between Acting Major John Brosnaham – a local doctor – and Lieutenant Richard H. Jackson, aide-de-camp for Brigadier General Lewis G. Arnold in charge of defending Fort Pickens. By May 12, Federal forces had taken possession of Pensacola and its fortifications. The South was now irrevocably deprived of a valuable port that could have been used for blockade-runners and the facilities at the Navy Yard. The West Gulf Blockading Squadron utilized the Navy Yard for repairs and resupplying, making it a vital depot for the navy efforts in the gulf until the end of the war.

Though it was claimed that Pensacola could “get along very well without foreign imports” the economy of the town was not immune to the effects of depreciating Confederate money prior to Federal occupation.[3] Privation was common, as “there was want and suffering but we drank our coffee of parched potatoes or meal, took dirt from the smokehouse floor and boiled it to get salt; dyed Osnaburg for their dresses and smiled, knowing it could be worse”[4] Secessionists left town with the Confederate forces and those remaining were forced to take the oath of allegiance or risk imprisonment at Fort Pickens. The much-needed manpower to rebuild the Navy Yard enticed citizens from the surrounding countryside to come to Pensacola for work and protection from Confederates that lurked in outposts.[5] Additionally, Pensacola became a beacon of freedom for the enslaved and by 1863, a school was established for the newly freed blacks.

Military activity within Pensacola before the spring of 1863 was limited to the regular occupation of the city, a picket line established five or six miles encircling the city, and expeditions into the outlying communities of Oakfield and Milton to ascertain Confederate strength. These intermittent skirmishes ensured the protection of Pensacola from any danger for the time being. Fort Barrancas and the Advanced Redoubt served as bases and launching points for these skirmishes that kept the Confederates at bay.

As plans were made to conquer the Mississippi River in 1863, Federal forces pulled out of Pensacola. The city itself was abandoned, but the forts and Navy Yard continued to be garrisoned. The evacuation was completed on March 22, and many citizens followed the troops to Warrington and Woolsey near the Navy Yard to benefit from their protection. Welles sympathized with the refugees, stating that “loyal citizens should be protected and not permitted to suffer.”[6] By early 1864, Unionist refugees were also encouraged to enlist in the Federal army, and many joined the 7th Vermont or the 14th New York Infantry at Barrancas. The condition of the city degraded after the evacuation. According to one observer after paying a visit, “Everything looks gloomy where once so much life and spirit prevailed, and a feeling of sadness seizes one to witness so much desolation.”[7]

The first – and only – assault upon the Navy Yard and Fort Barrancas occurred on October 8, 1863. Brigadier General James H. Clanton led 200 Confederates from the 57th and 61st Alabama Infantry, and the 6th and 7th Alabama Cavalry to the south side of Bayou Grande just north of Barrancas. A short-lived skirmish occurred around the Advanced Redoubt with the 7th Vermont Infantry and 14th Regiment Corps d’Afrique under the command of Colonel William C. Holbrook and ended in a Confederate retreat. Another skirmish occurred the following day, though there were no casualties on either side. Intelligence from a black cook that went by the name Old Tom, who had been captured during the skirmish and later released north of town, suggested that Clanton had led the expedition to scout the position of black pickets and “was only after the negro soldiers; that he would not fire on the white pickets, but that every black picket that could be seen would be shot.”[8] A regiment of black infantry 500 strong was thereafter sent from New Orleans as reinforcements, with another regiment promised within the following days. Other freedom seekers that came to the forts were incorporated into the 14th Regiment Corps d’Afrique. The skirmish proved to Clanton and his 1,000 troops around Pollard, Alabama, that they would not be able to contend with Holbrook at Barrancas without sufficient firepower.

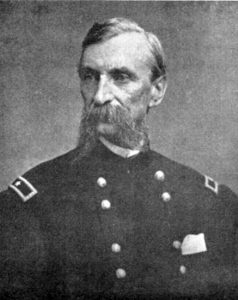

A false alarm sent the troops around Barrancas, the Redoubt, and the Navy Yard into a hurried effort to fortify their position. Commander of the District of West Florida Brigadier General Alexander Asboth heard rumor of an impending assault in November of 1863, spurring the reoccupation of Pensacola. Special Order No. 10 detailed the extensive preparations, including round-the-clock manning of the fortifications, and the strengthening of their trenches that stretched from Bayou Grande to the seashore.[9] By December, no assault came, and Asboth admitted that the Confederate activity around Pollard was of a defensive nature. Troops were withdrawn from Pensacola again.

These efforts prepared Asboth for a more serious threat that came in April of 1864 with reports of 10,000 Confederates concentrated at Pollard. Asboth wrote that his command was “entirely inadequate to secure a long resistance to a tenfold superior force.” He requested reinforcements and cooperated with Commandant William Smith on plans to evacuate the Navy Yard. He was denied reinforcements, but was ordered to hold Barrancas “to the last extremity.”[10] By May, Confederate forces diverted north to assist General Joseph Johnston in protecting Atlanta from General William T. Sherman. Only two cavalry units – the 15th Confederate and 7th Alabama – remained at Pollard, and the 82nd United States Colored Infantry arrived to Barrancas, relieving some of Asboth’s anxieties.

However, frustration over his denied requests for more troops and supplies only grew. Without the additional manpower, he could not make an offensive against the Confederates that lingered around Bayou Grande. Through 1863 and 1864, Asboth gradually received more regiments and cavalry to make raids, either west toward Mobile or east toward Milton, and sustained few casualties. After the battle at Marianna, Asboth was temporarily replaced by Brevet Brigadier General Joseph Bailey, who led successful raids to Milton and Bagdad. Bailey’s replacement, Brigadier General Thomas J. McKean, also initiated raids westward against forces under Brigadier General St. John R. Liddell out of Blakeley, Alabama. Most of these raids were to harass outposts or disrupt any supplies trying to make their way to or from Confederate lines.

A rapid buildup of troops took place in Pensacola in January of 1865, and soon after, Asboth resumed his command from McKean over the District of West Florida. As preparations were made for troops at Barrancas to embark with Major General Frederick Steele in the Mobile Campaign, all passage between Barrancas and Pensacola was restricted to military purposes only, while supplies for the expedition were routed to the storehouses around the Navy Yard. Steele’s command comprised a total force of 12,114, concentrated at Pensacola before setting out on March 20.[11] These troops would go on to fight in the Battle at Fort Blakeley on the evening of April 9, 1865, the same day Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox.

On April 22, Asboth received a letter from General Clanton that he would take the next available boat to arrive at Barrancas by the 26th. Cautious of any plot to attack the fort, Asboth ordered the new commandant of the Navy Yard, James Armstrong, to send an armed escort to bring Clanton to him. Asboth was authorized by General E.R.S. Canby to accept the surrender of Confederate troops in his district on the 29th, and that the parolees could return to their homes and would “not be disturbed by the authorities of the United States so long as they continue to observe the conditions of their paroles.”[12] In May, Asboth declared both Pensacola and Milton military posts, offering a safe haven for citizens from Escambia and Santa Rosa counties to take the oath, accept five days’ rations, and start their lives anew.

Troops from Barrancas were sent to Mobile and Blakeley for occupation duty, leaving a minimum of 60 men to garrison. By 1866, there were no troops at Barrancas or the Advanced Redoubt. Due to changing technologies in the latter half of the nineteenth century that made these forts nearly obsolete, the Advanced Redoubt suffered from neglect and vandalism.

When the fortification became part of the Gulf Island National Seashore in 1971, measures were taken to stabilize and restore the structure, as well as add signage to explain the redoubt’s history.

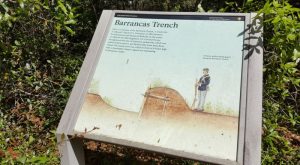

The Trench Trail from the Fort Barrancas parking lot to the Advanced Redoubt takes visitors through the woods along Taylor Road, pointing out the remnants of the entrenched line that Federal soldiers had used in 1863 and 1864. The interior was not accessible during my visit, and currently Barrancas, the Redoubt, and any other historical locations on the Naval Air Station in Pensacola are not open to the general public due to recent security incidents. It is hoped that a private civilian entrance will be constructed, and the forts will be open to visitors again.

The more popular aspects of Pensacola’s Civil War history has been restricted to the 1861 and early 1862 actions between Fort Pickens and Fort Barrancas. However, the story didn’t end there. The events of 1863-1865 illustrate the strategic importance of the area, not just for the blockading squadron that utilized the Navy Yard, but also for the land troops who used Fort Barrancas and the Advanced Redoubt as the launching point for raids and other major actions that took place along the Gulf Coast. The occupation of these fortifications also created a sanctuary for Unionists in northwest Florida and lower Alabama, providing protection and supplies – when they could be spared. The chance to enlist in USCI regiments was offered to for those seeking freedom as well as protection behind Union lines. For the men who were stationed at these forts, the shores of Pensacola Bay meant a great deal more than white-sand beaches.

Endnotes

[1] George F. Pearce, Pensacola During the Civil War: A Thorn in the Side of the Confederacy, Gainesville, University Press of Florida, 2000, p. 2

[2] The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (hereafter OR), Series 1, Volume 6, pp. 660-661; Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion (hereafter ORN), Series I, Volume 18, pp. 482-483

[3] Pensacola Daily Observer, January 30, 1862

[4] Mary Crary Weller and Marrie Crary Coley, “Civil War Reminiscences,” P.K. Younge Library of Florida History, Manuscript Collection, University of Florida, Gainesville.

[5] George F. Pearce, The U.S. Navy in Pensacola: From Sailing Ships to Naval Aviation, 1825-1930, Gainseville, University Press of Florida, 1980, p. 82

[6] ORN, Series I, vol. 20, p. 134

[7] Santa Rosa News Boy, June 15, 1863

[8] Ibid, pp. 617-618

[9] OR, Series I, Vol 26, part 1, pp. 822-823

[10] OR, Series I, Vol. 35, pt 2, pp 56-57; Ibid, p. 84

[11] Pearce, Pensacola During the Civil War, p. 226

[12] Edwin C. Bearss, Fort Barrancas: Gulf Islands National Seashore, Denver, Denver Service Center, National Park Service, 1983, p. 461

Excellent summation of post-Bragg Pensacola and the wartime use of its four forts. It is unfortunate that decades-long efforts to condense history have minimized the role of Pensacola to the point where Fort Sumter is the only potential flashpoint that schoolkids read about: newspapers of 1861 stressed the “possible eruption of war at Fort Sumter OR Fort Pickens.” Pensacola and its rich history have been mostly overlooked… until now. Thanks for helping reverse the trend by providing reports that reveal the neglected story of Pensacola: where the Civil War almost began.

I was pleasantly surprised to learn that Pensacola continued to play a significant role in the war in this part of the country after 1862. In school, it was all “For Pickens!” and that was it! Just goes to show that stuff was happening the whole time during the war.

Another often-neglected fact: some of the earliest Civil War photographs were taken of Rebel/ Confederate soldiers in vicinity of Fort Barrancas, Fort McRee, the Advanced Redoubt and the Pensacola Navy Yard. It appears New Orleans-based photographer, J. D. Edwards, accompanied Braxton Bragg to Pensacola in March 1861, and got to work. Many of Edward’s 40+ images may be accessed via the internet (although some are miss-labelled) and it is uncertain just how many photographs were taken, in total, because a complete set is nowhere to be found. But the most complete collection is on file with the New York State Military Museum (where Jim Gandy is Librarian/ Archivist) due to a New York regiment entering CSA Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory’s Pensacola house and “helping themselves” to the bundle of photographs discovered there.

New York State Military Museum https://museum.dmna.ny.gov/