The Ely/Faulkner Exchange Part I

ECW welcomes back guest author Max Longley

New York Congressman Alfred Ely, imprisoned in the South, and Virginia ex-Congressman Charles James Faulkner, imprisoned in the North, traded for each other in 1861 after each spent a few months in the military prison systems of the different belligerents. The story begins with Congressman Ely’s capture at the battle of First Bull Run and, later, by Faulkner’s imprisonment on returning from a diplomatic post.

Republican Congressman Alfred Ely of Rochester, New York, who represented Monroe County of which Rochester was county seat, had come to the Bull Run battlefield to check up on the 13th New York Volunteers, a unit he had helped recruit from his upstate New York district. So long as they were in the area, Ely and his friend Calvin Huson, Jr., a fellow-lawyer and one-time political opponent in Rochester, decided to observe what they could of the battle, disembarking from their carriage and proceeding to view events from what they supposed to be a position of safety.[1]

Ely had gotten a little too close to the Union defeat of July 21, 1861. As the Confederates came through his position, they saw him. A Confederate officer, apparently somewhat inebriated, threatened to shoot down the Republican congressman. Other Confederate officers, presumably more sober, dissuaded their colleague and took Ely into captivity. Ely was brought to Richmond where he was housed with captured Union officers in a wing of Libby Prison, one of the old tobacco warehouses being used as military prisons.[2] Huson, who initially fled from the Confederates, was captured soon after that and brought to the prison, too. As a Congressman, Ely had spoken against secession, the Confederacy, and against accommodating slavery through compromise. Now, slavery’s defenders were accommodating him in Richmond’s Libby Prison.[3]

Around August 12, 1861, in Washington, D. C., the U. S. military arrested Charles James Faulkner – he would get different explanations for his arrest as time went on. Faulkner had just come back from his stint as American minister in Paris. He had just debriefed his former boss, Secretary of State William Henry Seward, about his mission, and after this seemingly-friendly encounter he had gone to his hotel, preparing to leave for his home in Martinsburg, in the contested county of Berkeley, Virginia.

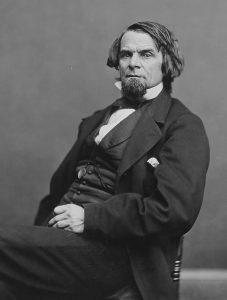

At his Boydville estate in Martinsburg, his journey to which had been interrupted, Faulkner had built a profitable legal career, supplemented by a generous inheritance. He had also taken up a political career, giving an antislavery speech in the Virginia legislature in 1832 – and William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator assured the speech’s fame by frequent reprinting. Soon Faulkner was reconciled to slavery, owning slaves and helping, as a state legislator, to press for the federal Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 (for which he took credit). By the curious political taxonomy of the time he was a moderate because, while serving in Congress in the 1850s and even before, he preached the virtues of union and of North/South compromise. After he lost his Congressional seat in 1859, President James Buchanan sent him to Paris, whence he had come by a roundabout route to a Washington prison.[5]

In his uncomfortable quarters in Richmond, Ely received visits from many Confederates who had been Congressional colleagues of his in prewar Washington. From some of these associates, including former Vice President John C. Breckenridge (former Southern Democrat candidate for President, now a Confederate general), Ely received hints that the Jefferson Davis administration might release him, but such action was not forthcoming. Many curiosity seekers came to Ely’s prison, some of whom Ely agreed to receive as visitors.[6]

The captive Congressman was able to perform a sad duty of constituent service. Private John B. Nichols, a soldier who was the son of one of Ely’s constituents, had been wounded and captured at Bull Run and died in prison in Richmond on August 8, 1861. Ely arranged for Nichols to be buried in a humble but marked grave in a Richmond cemetery, so that the body could later be identified and moved to his family’s home, which is what seems to have happened – Nichols is now buried in Monroe County, New York. While he is somewhat shy on the subject in his journal, Ely’s obituary credits him with tending Union soldiers in prison, helping them out of his own pocket, and assisting in arranging their release or exchange in some cases.[7]

Ever the lawyer, Ely wrote to Confederate Secretary of War Judah Benjamin – a former Congressional colleague – on September 26 to ask on which charge he was held beyond his membership in the U. S. Congress. To Ely, holding him, a noncombatant, as a prisoner of war was illegal unless he was charged with some offense. Benjamin disagreed, curtly sending Ely a message on September 28 that Ely was being held as a prisoner of war, and no charges were required.[8]

Benjamin was also caught up in Faulkner’s imprisonment. Secretary of War Simon Cameron wrote Faulkner that the latter was being held for the release of James Magraw, a Lancaster, Pennsylvania politician who had been captured by Confederates while searching the Bull Run battlefield for the body of a dead Northern officer. That officer was James Cameron, brother of Secretary Cameron. Senator Reverdy Johnson, a pro-Union Senator from Maryland, wrote Benjamin to propose exchanging Faulkner for Magraw. Benjamin replied to say that Magraw had already been released on recommendation of a special Confederate commission, and that the Magraw case had no connection to Faulkner. Benjamin deemed Faulkner a victim of unjust imprisonment whom the North should release unconditionally – Benjamin said he wanted to show no favoritism in prisoner exchanges.[9]

Cameron, in any case, had informed Faulkner that he (Faulkner) was out of War Department custody and under the responsibility of Seward, who in addition to his responsibilities as Secretary of State handled the cases of Northern political prisoners – who could be locked up, the Lincoln administration claimed, without habeas corpus or even (as in Faulkner’s case) without trial. In Washington, Brig. Gen. Joseph Mansfield and U.S. Attorney Edward C. Carrington helped Seward gather statements implicating Faulkner in disloyal activities. The reports, which Seward examined ex parte without Faulkner being able to rebut them, variously indicated that a Confederate command awaited Faulkner in Virginia if he returned, that Faulkner and his family had expressed support for the Confederacy while in Paris and afterwards, and that in September 1860 (before Virginia’s secession), Faulkner had sent samples of newly-developed French weapons – four rifles and two bayonets – to Virginia. Faulkner never got a trial on these charges, but his biographer Donald Rusk McVeigh doubts the accusations were true – or at least McVeigh thinks Faulkner would have been able to give innocent explanations for some charges (e. g., McVeigh says Faulkner was supposed to send samples of new French weapons to the various states).[10]

Seward had Faulkner sent to Fort Lafayette in New York harbor, a military fort converted into a prison. On September 11, Seward sent a note to Faulkner that the ex-diplomat was being held because he acknowledged the authority of secessionist Virginia. Captured blockade runners, secessionist prisoners from Maryland, and Northern and Southern opponents of the war effort, and alleged Confederate sympathizers, were also among the Fort Lafayette prisoners. Faulkner and other prisoners signed a petition complaining of the conditions of their confinement, including exposure to the elements, and compared the conditions at Fort Lafayette to those of an African slave ship.[11]

For the average inmate at Fort Lafayette, the crowded and exposed conditions were made worse by the rations. The drinking water swam with fish and tadpoles. One prisoner said breakfast was “some discolored beverage, dignified by the name of coffee, a piece of fat pork, sometimes raw and sometimes half cooked, and coarse bread cut in thick large slices.” Lunch was supposedly bean soup, but there were precious few beans. For supper the inmates dined on “tea or coffee, in the inevitable greasy tin cups, and slices of bakers’ bread.” For the elite-class Southerners in the fort, and their associates, things were somewhat better on the culinary front. The high-class prisoners formed an invitation-only eating club. Members of the club purchased food from shore and held meals made even more pleasant by conversation and droll stories.[12]

Ely was the head of a similar prisoners’ club, the Richmond Prison Association. This group of officers (plus the civilian Ely) held meetings to enliven prison life, to bid farewell to colleagues who were shipped to other prisons in the South, and on one occasion, amid much hilarity, to present Ely with a wooden sword.[13]

Things took a somber tone when the Confederates contemplated reprisals for the treatment of a Confederate privateer, the Savannah. The captured crew were held for trial in New York City as accused pirates. The Confederates proposed to hang Union prisoners in retaliation for any privateers hanged, raising the possibility of a cycle of reprisals, as Ely learned from a discussion of the Lincoln administration’s deliberations in the Philadelphia Inquirer. Ely would be among those hanged in reprisal hanging the privateers, the imprisoned Congressman read, and Faulkner would be among those hanged in the North in reprisal for the reprisal. Ely’s captors, instead of threatening to hang him, assigned him a different role – helping decide who would hang. On November 10, the authorities called on the Congressman to draw lots for hostages among the Union officers, who were to suffer whatever the North inflicted on the Savannah crew, up to and including execution. The officer-prisoners persuaded a reluctant Ely to draw the lots – in the end the privateers were spared (Lincoln decided to treat them as POWs rather than as pirates to avoid reprisals), and the selected hostages were spared as well.[14]

Ely’s friend and fellow-prisoner, Calvin Huson, fell seriously ill. Constantly tending Huson in his cell, Ely, backed by the officer-prisoners, pleaded for Huson’s release. Though he couldn’t achieve this – perhaps the Confederates didn’t like Huson’s close connections to the hated Secretary Seward – Ely persuaded Confederate authorities to move Huson to a private home in Richmond where he could get medical attention in better circumstances than Libby Prison. A prisoner who served as nurse was also moved to accompany Huson, thanks to Ely. Huson was thus transferred to the house of Elizabeth Van Lew, a wealthy Richmond widow known for her charity to Union prisoners, and indeed subject to suspicion of Yankee sympathy. Ely was allowed to visit Huson in the Van Lew residence. (Did he learn that Huson’s hostess was in fact a spy for the Union?) Despite Van Lew’s care, Huson died on October 14, and Ely arranged a burial, and even a graveside funeral service, in the prestigious Shockoe Hill Cemetery in Richmond, held in a subdued manner under the watchful eyes of Confederate guards.[15]

Max Longley is the author of Quaker Carpetbagger: J. Williams Thorne, Underground Railroad Host Turned North Carolina Politician (McFarland, 2020), For the Union and the Catholic Church: Four Converts in the Civil War (McFarland, 2015), and many articles. He is on Substack (https://maxlongley.substack.com/about) where he is working on articles about various topics, definitely including the Civil War.

[1] Alfred Ely (Charles Lanman, ed.), Journal of Alfred Ely, A Prisoner of War in Richmond (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1862, 8-15); “Hon. Alfred Ely,” Rochester (NY) Democrat and Chronicle, May 19, 1892, 8.

[2] Ibid, 15-23, 27.

[3] “Hon. Alfred Ely;” “The State of the Union. Speech of the Hon. Alfred Ely, of New York, Delivered in the House of Representatives, February 18, 1861,” https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=loc.ark:/13960/t8z89bg7n&view=1up&seq=3&skin=2021; “The Revolutionary Movement. Letter from Hon. Alfred Ely. From the Rochester “Democrat and American” of Jan. 15, 1861, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=loc.ark:/13960/t55d8xc00&view=1up&seq=5&skin=2021

[4] Donald Rusk McVeigh, Charles James Faulkner: Reluctant Rebel (Morgantown: PhD Dissertation, West Virginia University, 1954), 123-26

[5] McVeigh, 12, 19-32, 37-38, 41, 44, 46,47, 50, 52, 59-60, 67, 71-111; F. Vernon Aler, Aler’s History of Martinsburg and Berkeley County, West Virginia (Hagerstown: The Mail Publishing Company, 1888), 318 (which also attributes the following remark to Faulkner: “but for this impertinent and illegal intermeddling of Northern fanatics, emancipation would have become the predominant sentiment of Virginia, and would have worked out its results without ruin and bloodshed.”)

[6] Ely, 26-28.

[7] Ely, 47-48, “John B. Nichols,” https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/20326139/john-b-nichols; “Hon. Alfred Ely.”

[8] Ely, 140-41, 145-46

[9] Aler, 331-32. Johnson to Benjamin, September 26, 1861; Benjamin to Johnson, September 30, 1861; in War of the Rebellion: Serial 115, Prisoners of War, etc., 476-477, https://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/115/0476. For news of Magraw’s release, see “Returned,” Reading Times, October 8, 1861, 2; “Return of Mr. Magraw,” Lancaster Examiner, Oct. 9, 1861, p. 3.

[10] Mansfield to Seward, August 12, 1861; Mansfield to ?, August 12, 1861; Seward to Carrington, August 14, 1861; War of the Rebellion: Serial 115, Prisoners of War, etc., 464-65; McVeigh, 120-21. Some, but not all, of this information was provided by a personal enemy of Faulkner’s. McVeigh, 92-93, 119-21. For Lincoln’s attitude toward habeas corpus, see Mark E. Neely, The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Habeas Corpus (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991).

[11] Petition of October 8, 1861, Charles James Faulkner papers, Rubenstein Library, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina; War of the Rebellion: Serial 114, The Maryland Arrests, 649 ff.

[12] Dean Sprague, Freedom Under Lincoln (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1965), 5, 12, 189-90, 209-11, 282-83; Faulkner to James McMaster, October 26, 1861, James McMaster papers, University of Notre Dame Archives (UNDA), Calendar.

[13] Ely, 32, 113-14, 245

[14] Ely, 114-16, 129, 148, 209-15; Leon Reed, “19th Century Asymmetrical Warfare: Privateering, the Savannah, and the Enchantress Affair,” Emerging Civil War, May 29, 2020,

[15] Ely, 151-70; “ECW Weekender: Elizabeth Van Lew,” Emerging Civil War, March 1, 2019, https://emergingcivilwar.com/2019/03/01/ecw-weekender-elizabeth-van-lew/. Huson is still buried in Richmond, see https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/156819141/calvin-huson

This is a Great Achievement by Max Longley, introducing this serpentine, hazy aspect from early Civil War history in such an engaging, clear manner. It must be remembered that pre-Bull Run Washington was filled with spies (Thomas Jordan and Rose Greenhow spring to mind) and the loyalty of everyone to the Union was under suspicion. John C. Breckinridge, as a different sort of example, remained as U.S. Senator from Kentucky until December 1861 while serving at the same time as Brigadier General in the Confederate Army (perhaps this entitles former-VP Breckinridge claim to the title: First Double-Dipper?)

As for Charles J. Faulkner, the life-long politician and onetime opponent of slavery had “seen the light” and subsequently supported the institution at the time of his appointment by President James Buchanan as U.S. Minister to France in January 1860 (replacing John Y. Mason, who had died in office.) While in Europe, Minister Faulkner expressed the view that “America’s current unrest is temporary, and will be resolved peacefully,” while at the same time there was suspicion that he had facilitated the meeting of Confederate agents attempting to buy arms with European arms dealers. [John C. Fremont was in Europe at about the same time, attempting to purchase arms for the U.S. Government.]

In sum: the period January – August 1861 was fraught with uncertainty as newly-belligerent CSA and USA sought to “find their feet” and determine rules of engagement. Without Letters of Marque, the privateers would rightly be considered pirates. But, once reprisals commenced, where does it stop? There was fear (in USA) that “recognizing rights of prisoners” would equate to “recognition of the Confederacy as a sovereign authority.” [Recognition of the Confederate States of America as sovereign NATION, independent of the USA, was one of the goals of the CSA and its Rebellion.]

Take away “slavery” (which was legally practiced in the USA) and there was no real right versus wrong; no “high ground” during the early contest. In the same way that Might Makes Right, the outcome of the Rebellion itself would determine “results,” and along the way to that outcome a few issues, by necessity, were resolved.

thank you for bringing this little known tale to light — fascinating story … looking forward to part 2.

Jefferson Davis nixed the reprisal hangings. He was angry with the threat of Confederates being executed and did express an interest in retribution against Union prisoners, but ultimately he thought the better of it and saw that it would just lead to more Confederate prisoners being executed.