Who Lost The “Lost Order”?

ECW welcomes back guest author Lloyd W. Klein

General Robert E. Lee issued Special Order #191 on September 9, 1862. The order directed his corps commanders’ movements for the start of the Maryland Campaign. Soldiers of the Union army found a copy of the order on September 13, and it has subsequently become known as “The Lost Order”. The Lost Order revealed that each part of the Confederate Army was separated by several miles from the others and that the two largest units were 20 to 25 miles apart on either side of the Potomac River. This military intelligence likely encouraged Major General George McClellan in his planning and to advance his army with confidence, and is traditionally considered to have been an important influence in the Battles of South Mountain and Antietam.

What was Special Order #191?

In Special Order #191, General Lee outlined in detail the routes his army would take during the invasion and the timing for the attack of Harpers Ferry. The crucial aspect of Lee’s plan was to divide his army during the early part of the invasion, and then regroup later. Lieutenant General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson was to lead the advance and capture Harper’s Ferry while Major General Daniel Harvey Hill was ordered to guard its rear.

Lieutenant Colonel Robert H. Chilton, Lee’s assistant adjutant general (chief of staff), wrote out 8 copies of the order while at Lee’s camp on the Best farm, 3 miles south of Frederick, MD. These copies were transcribed and sent to each of the generals involved and to President Jefferson Davis by courier.

Union troops discovered a copy of the order 4 days later in a farm field about half a mile north of where Lee’s camp was located. The order was in an envelope wrapped around three cigars lying in the grass at a campground that General Hill and his command had recently vacated.

Whose Copy of the Order Was Lost?

Chilton unquestionably wrote the copy of the order found in the field. Hill did receive a copy: but it is in Jackson’s handwriting, not Chilton’s. Hill was adamant for the rest of his life that he only ever received this one copy. The mystery of the loss of the Order centers on the fact that Hill received the copy written by Jackson, which he kept forever, but not the copy from Chilton. That copy is the “Lost Order.”

The presence of duplicate orders to the same general is the foundation of this mystery, and provides some insight into what happened. At the time that Special Order #191 was written, Hill was under the command of Jackson, his brother-in-law. Jackson personally copied the document for Hill, because once the army crossed into Maryland, the order specified that Hill was to exercise independent command as the rear guard. For this reason, Jackson copied and sent Hill the order because he didn’t know if Chilton had done so. But, since Special Order #191 conveyed Hill’s having an independent command once entering Maryland, Chilton had in fact sent Hill a copy.

Chilton did not learn of the order having gone missing until a year later when it was revealed as part of a US Government investigation. He was surprised to learn of it because the envelope should have been returned signed by the receiving staff officer, otherwise an inquiry would have followed. He did not know why this missing envelope was never recognized. Years later, Chilton could not remember which officer he had dispatched as a courier to Hill.

Plausible Candidates for the Culprit

To this day, no one knows who lost the order. There are only three plausible candidates: Chilton’s courier, a member of Hill’s staff, or Hill himself. This order dictates the overall strategy of the Army of Northern Virginia in a major offensive operation. How did such an important document end up in a farmer’s field still in the original envelope?

One obvious clue is that whoever last had possession was a cigar smoker. But it can be deduced that the presence of the cigars, which was not disclosed for 2 decades after the war, is even more meaningful. The detail of personal cigars in the envelope demonstrates that this copy of the order had either been delivered or was never going to be delivered, since the envelope was serving as a humidor. Also, it suggests that it was undoubtedly “lost”; if it had been purposely discarded, the cigars would have been removed.

We can reason that whoever last possessed the order must have known that it was not, at the moment of the loss, of proximate importance to General Hill. This is a logical deduction because otherwise its loss would have caused immediate difficulty and prompted an immediate search. Further, since Jackson had to have received the order (he was in the same field at the time as Lee), written his version, and had it delivered to Hill, its loss can be presumed to have occurred later than the initial deliveries of Chilton’s copies. It was found in Hill’s abandoned camp, which is less than a mile from where Lee was, implying that it did get to the right place.

The most frequently postulated possibility is that Hill did receive both orders, and lost one of them. After the war, this was the standard view, but Hill always denied it. He expected that his orders would come from Jackson, his superior officer, so the fact that none came from Lee did not surprise him. He claimed that he had pinned the version he had received in his pocket, knowing its importance. His chief of staff always maintained that only one version was received. After the war, Hill even sent a letter to Lee detailing the events and asking for clarification. He carried the copy he had received to show to everyone that he, indeed, had kept his copy of the order. Hill was a highly intelligent but cantankerous individual who was an excellent battlefield general; it is hard to imagine someone of his caliber losing such an important document. He was a very religious man who has not been reported to smoke.

Hills’ chief of staff also denied receiving two copies, saying that had an order from General Lee arrived at headquarters, it would have been handled carefully and with documentation: it would have been stamped and the return envelope signed and returned to the courier. Certainly, no cigars would have been placed in the envelope. Major James W Richford was Hill’s adjutant general, who gave sworn testimony that it was his duty to receive such orders and the only one he ever saw was that from Jackson. The fact that the envelope was not signed by him is strong supporting evidence that it was never formally received.

Another possibility to consider is that the culprit was the courier, who accidentally dropped the envelope while on his way to deliver it to Hill. But the distance from Lee’s headquarters to Hill is less than a mile, a few minutes ride by horse, and no courier would have found that an opportune time to open a dispatch from General Lee and place his cigars in the envelope. Moreover, the orders were found near Hill’s camp, not along a road or in the bushes.

Having discarded the simple explanations, a more complicated story must be hypothesized. One key question is: why was Chilton lax about checking whether the envelope was returned signed, as was the standard practice?. He was a highly conscientious officer and his subsequent activities during and after the war demonstrate a decidedly competent, detail-oriented man. His denial of remembering who was the courier was made in a letter to Jefferson Davis in 1874. It is at least as credible that Chilton knew exactly who he had sent with the orders and was covering up the identity years later. Doing that would be surprising if the man didn’t survive the war or had descended to obscurity, but would be exactly the honorable thing to do if the man was prominent and still alive, and whose reputation would be harmed.

So, Who Lost The Order?

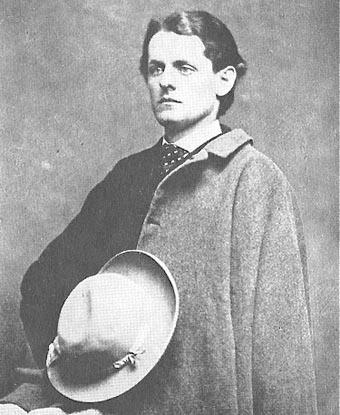

If that were the case, a very serious candidate would be Henry Kyd Douglas. He has been considered a potential culprit, though there is no direct evidence.

Kyd Douglas was a young lieutenant on Jackson’s staff at the time of Antietam, often serving as courier. It is not a stretch to conjecture he was at Lee’s HQ having just delivered dispatches, and that Chilton asked him to drop off the order at Hill’s encampment, just up the road. Douglas might have recognized on his arrival that Hill had already received orders from Jackson and never formally delivered them, or tried to but was told it had already been received. Perhaps before returning he stopped for refreshment in the camp and the envelope fell from his pocket. He could have returned to Jackson without the envelope without any alarm, since the orders called for advancing early the next morning.

He was a great asset to the Confederate leadership at Antietam because he grew up about four miles from the battlefield. He left Jackson’s staff in October – 1 month later – a fact that some have speculated was retribution for losing the order. He was appointed Captain of Co. C of the 2nd Virginia Infantry and later appointed Inspector General of the “Stonewall” Brigade. Afterwards, he joined the staff of General Edward Johnson, and was promoted to Major. He was wounded and captured at Gettysburg, and held as a prisoner at Johnson’s Island, Ohio, until exchanged in March 1864. He was later staff officer to Generals Gordon and Early, and saw action in the Overland, Shenandoah Valley and Petersburg campaigns. He commanded a Virginia brigade at Appomattox. He was involved as a witness in the investigation of the assassination of President Lincoln, but he was not implicated.

Wounded six times, Henry Kyd Douglas returned to the practice of law in Maryland after the war. He was a very popular speaker and a respected trial lawyer. He also was prominent in veterans affairs; he helped to establish a permanent cemetery in Hagerstown, Maryland, for Confederate soldiers killed at Antietam. He was involved in local politics, running unsuccessfully for Congress and serving briefly as a justice on the Maryland Court of Appeals. Why would Chilton damage his reputation unnecessarily after the war by identifying him?

Douglas’s memoirs, I Rode with Stonewall: The War Experiences of the Youngest Member of Jackson’s Staff, are not considered reliable; they are said to be filled with exaggerations. They do not relate where he was at the critical time on September 9th.

Incidentally, he smoked cigars.

Dr. Lloyd W. Klein is Clinical Professor of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco. He is a nationally recognized cardiologist with over thirty-five years’ experience and expertise. He is also an amateur historian who has read extensively and published previously on the Civil War, with a particular interest in political and military leadership and their economic ramifications.

Further Reading:

- Stephen W. Sears, Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom. The Civil War Era. Oxford University Press, 1988.

- General Robert E. Lee’s “Lost Order” No. 191 https://www.battlefields.org/learn/primary-sources/general-robert-e-lees-lost-order-no-191

- Joe Ryan. “Special Order 191: Ruse of War”. Joe Ryan Civl War.com. https://www.joeryancivilwar.com/Special-Order-191/Ruse-of-War.html

- Wilbur D Jones. “Who Lost the Lost Order? Stonewall Jackson, His Courier, and Special Orders No. 191.” Civil War Regiments: A Journal of the American Civil War, Volume 5, No. 3, 1997; and http://www.geocities.ws/Pentagon/Barracks/3627/loser.html

Isn’t there an account of D.H. Hill taking up a musket at Antietam and cooly smoking his cigar as the Yankees attacked?

If I recall correctly, his memoirs were re-titled by critics as Stonewall Rode With Me.

Bob Krick, Sr. I believe, gave it that name.

Alex Rossino’s “Their Maryland” has an outstanding chapter on this issue–the most comprehensive analysis to date. Lots of new things there.

https://www.savasbeatie.com/their-maryland-the-army-of-northern-virginia-from-the-potomac-crossing-to-sharpsburg-in-september-1862/

Agree. A book well worth getting.

The chapter, “Implications of the Lost Order,” contains a map which the author created out of his imagination, to place D.H. Hill’s four brigades about a mile south of the location of the Best farm at Ballinger Creek. The author provides twenty pages of dense script to tell us where Hill’s headquarters probably was located, this based on inferences and assumptions drawn from both original material, such as the diaries of Jed Hotckiss and William Owen, and romantic civil war writers such as Mr. Harsh and company.

The purpose of the exercise, which is well done in the detail, is to look at the question, Where was the order found?,” by attempting to establish where D.H. Hill’s “headquarters” was located, relative to the supposed location of Lee’s headquarters at the Best Farm.

All of it is speculative and, in any event, irrelevant. The better direction is to answer the question,Where was the order found?, by focusing on the width of front of the skirmishers of the 27th Indiana, as they approached the Monocacy, crossed the stream and moved forward to the point Mitchell and his fellows began to stack arms, sometime about 10:00 am. on Sept. 13.

The detail underpinning the answer to this question the author ignores, but, notwithstanding, he summarily announces, correctly, that the order was found at or near what is marked on the 1860 map (which he does not cite) held by the Library of Congress) as the location of the Delashmutt farm–today it is a huge quarry pit.

The author, falling into romance, asserts the reason it was found at this location was because Delashmutt was a Confederate. Whether he was or no, who knows? Many of the Frederick townspeople and farm folk were Confederate in sympathy. The important investigation that points to the answer, why here?, must be on the situation the skirmishers encountered when they came to stack arms. The division had been ordered to halt and camp. The enemy were long gone, Pleasonton was riding after them, followed by Burnside’s infantry. The Delashmutt farm is hardly a half mile from the Frederick city limits. How many civilians, men, women, and children, with flags and cheers, came to mingle with the arriving skirmishers? One of them, from the folds of her dress, with a man on her arm, might easily drop the package between them as they walk on.

The greatest romanticist of them all, Stephen Sears, wrote the scene forty years ago: “The town jubilantly welcomed the liberators. `Handkerchiefs are waved, flags are thrown from Union houses, and a new life appears infused with the people.’ The troops responded with volleys of cheering, and regimental bands blared. . . `The place was alive with girls going around the streets in squads. . .’ The townspeople did not restrict their welcome to these early arrivals. . . . It was like a giant Fourth of July celebration.” (Landscape Turned Red, at p. 111.)

Dear Mr. Ryan. If you consider using the sources to determine where Hill’s men camped creating the location out of my imagination you really ought to stick to the practice of law because your skills as an historian are abominable. Moreover, no fewer than 7 sources show that the Twelfth Corps did not stop to stack arms until noon on Sept. 13. Please educate yourself better before casting aspersions. Also, I am clear in Their Maryland that the exercise suggesting the Delashmutt location is speculation. Unlike your theories, I do not contend anywhere that the scenario I outline is THE answer. Rather, I suggest it as a possibility. This is not romance. It is using the available information to come to a reasonable conclusion. If you disagree by all means prove your assertions. You don’t, which is the reason no one in the field takes you seriously.

In Special Order 191: Ruse of War, the revision as it is today, I cite your book for the location of D.H. Hill’s camp, though it is based imagination, it is a location in the ball park. The relevant location, however, is where Hill was located (in Frederick?) and where his headquarters staff was located; somewhere within say a mile radius of Lee’s staff’s tent? I provide the current revision as a readable file at the YouTube site Joe Ryan’s Trial Book, under the video “Sears’ concept of History.”

Thanks for this Dr. This kind of medicine makes me well. May meditate with a Gloria Cubana upon the matter.

My pleasure. It’s a topic I have been thinking about since I was a teenager.

Thanks Dr. Klein, I appreciated your tight summary of the sources and thoughtful conclusion. The blame for this incident is on Chilton. With no proof of delivery – an envelope signed by one of Hill’s staff officers and no recollection by either Hill or his Chief of Staff of ever receiving the order — Hill is off the hook. In modern parlance, an order unacknowledged is an order undelivered.

I also found it interesting that Chilton felt the need to issue the order directly to one of Jackson’s subordinates. That’s not unheard of, but it is somewhat unusual. “Jumping” the chain command often results in chaos which is why military orders follow the echelon of command – army-corps-division-brigade, etc. Therefore, it makes perfect sense that Jackson issued Lee’s order directly to Hill, whether or not Jackson knew about copy.

Finally, I also found your theory about Kyd Douglas very persuasive. Thanks again for a great essay.

Chilton certainly seems to have not followed good management principles. Which is precisely what makes me doubt the traditional story. He was not the kind of man to do that. So to me, that requires some explanation, and so the idea that he knew who it was and protected him is highly plausible. But it is speculation.

Thanks for reading!

Charles Venable gave the “lost” order to his sister-in-law, The Rev.Dr.John Ross’s wife, who dropped it in the field as she passed Barton Mitchell stacking his rifle.

Venable got the copy he gave to Mary Ross from Stonewall, who had his chief of staff, R.L. Dabney, copy in his hand the copy Stonewall had made in his hand. Stonewall gave D.H. Hill his handwritten copy and he gave Venable Dabney’s handwritten copy. Conclusive proof of this depends upon whether the handwriting on the copy of the order in the hands of the Library of Congress matches Dabney’s.

This is what passes as “history” for you? Where is your evidence?

The material is presented now as an e-book, Special Order 191: Ruse of War, and the “evidence” is of the quality that must be produced in the trial court, as opposed to guys talking among themselves at a round table.

“It is not a stretch to conjecture [Douglas] was at Lee’s HQ having just delivered dispatches, and that Chilton asked him to drop off the order at Hill’s encampment, just up the road.” Amazing, adults substituting the imagination of children for serious objective analysis of facts.

Douglas and his post war writings do have relevance to the question whether Jackson actually conferred privately with Dr. Ross. According to the folk lore, when Jackson crossed the Potomac, someone presented him with a horse which promptly threw him, causing some soreness if nothing else. This induced him, the story goes, to ride in an ambulance during the time he was in Frederick. Some even wrote after the war that he was in an ambulance when he was leaving on the 10th, and thus never encountered Fritchie.

Dougjas published a piece in the Century Magazine, in 1884, titled “Stonewall Jackson in Maryland.” In the piece, after telling us about the ambulance business, Douglas wrote this text: “Early on the 10th Jackson was off. In Frederick he asked for a map. . . he told me that he was ordered to capture the garrison at Harper’s Ferry. . . .I did not know then of General Lee’s order.” (Vol II, Part II, at p. 622.)

Some sixty years later, the UNC Press published a now disappeared manuscript under the title “I Road with Stonewall.” The editors today cannot tell us where, or from whom, the manuscript came from and no copy of it was kept by UNC. The manuscript repeats the text of the 1884 piece but with an addition. It reads: “At daylight on Wednesday, the 10th, Jackson was in motion. About sunrise he and his staff rode into Frederick. . . He asked his engineer for a map. . . I did not know of General Lee’s order. . . He said he was ordered to take Harper’s Ferry. . . The general was anxious. . . to see the Rev. Dr. Ross. . . and I took him to his house. The doctor was not up yet and the general. . . wrote a brief note and left it with a manservant on the pavement to deliver to him.” (at p. 151.)

In 1870, in a letter to the editor of the Baltimore Sun, disputing the Fritchie encounter story made popular by Whittier’s poem, a lawyer whose family was prominent in Frederick in 1862, said that he had received at the time the text of Jackson’s note from Mrs. Ross and he quoted it as it is reflected in several copies floating about the auction houses these days. The original note has not been found identified in the papers of Mrs. Ross’s estate, of which Charles Venable was Executor.

As a practical matter the note business makes no sense, other than, if the event happened, as a show; to show the people that Jackson did not actually confer privately with Dr. Ross; a show meant to diminish the idea among the people that Ross, being a Confederate in mind-set, had any part to play in what it turns out unfolded. Nor, did Jackson have a need to make a public appearance at Ross’s door, as he and Lee’s staff officers had spent most of their time in Frederick at the home of a lawyer named John Ross, which was located a few doors up Record St from Ross’s Manse. Any of them in the night could easily have entered Ross’s Manse unseen. In the reality, the most likely Confederate to visit privately with the Rosses would have been Mrs. Ross’s brother-in-law, Charles Venable, General Lee’s chief of staff.

As I recall, Douglas was ambiguous about the matter in his book. I think he noted that the matter had “never been satisfactorily explained” or words to that effect. Also, are his personal papers still being kept private by one of his descendants, and therefore not available to historians?

Good stuff, Lloyd. Never heard the Douglas angle.

Interesting! The Douglas theory seems possible…and he certainly would have never confessed. Ha.

The cemetery is in Shepherdstown, Wv, not Hagerstown, Md.

Great article here! There remains so much myth and mystery about this event. To my knowledge no definitive time has been established as to WHEN RE Lee himself learned of the missing order. He did muse that he believed it changed the ‘character’ of the campaign, and that had it not been discovered by the Union’s troops, he would have had a few more days to draw his separated forces together and to have them rested, and he would have retained the initiative (though he also added that he couldn’t know if any of that would have resulted in victory for his forces).

Some sources say Lee learned of the order being lost in early 1863 from newspapers that reported on McClellan’s testimony before Congress. There are reports of a spy, or at least a Confederate sympathizer, being among a group of ‘citizens’ who had an audience with McClellan where he bragged about having information that could be decisive against Lee, and that person.afterwards passed the info on to a Confederate officer who in turn got it to Lee. Some have deduced that Lee determined that McClellan thus knew of the Lost Order’s contents, but does that mean that Lee KNEW that a copy had been lost by then? That seems unlikely. Seeing how DH Hill had a copy of the order direct from Stonewall, did Stonewall ever comment on what did or might have transpired before his death in May 1863?

I have this question. We do know that two copies of the order were made specifically for DH Hill. We do know that he received and acknowledged receipt of the one that Stonewall Jackson had written out for him. But why would there be an assumption that he did not receive BOTH copies, from Jackson AND everyone’s boss RE Lee? In the fluid, at times fast-paced, and often confusing, not to mention complicated and complex movements of many Confederate army units large and small, Hill being communicated with directly by Lee makes sense. The fact that there are two known copies bears that out, in that the chain of command (Hill was part of Jackson’s force) was still adhered to, or at east an effort was made concerning that. Which to me begs another question: why would Hill NOT officially receive both copies? And why would any courier thus NOT deliver them? That alone, despite his protests and assertions of his ‘innocence’, points heavily to Hill. I don’t know if Hill smoked cigars, but it doesn’t seem unthinkable that he might have got hold of some to pass along to someone. And that could apply to anyone who might have had custody of the order.

But, as mentioned, it was a fast moving, ever-changing set of circumstances in play on all this. Because of that, might the bearer of the order that was lost, have been someone not usually employed in such a capacity? If messages are being sent out in a rapid fashion, an order could go out along the lines of “get me someone, anyone”, who can ride a horse and deliver a message, or order. It could have been handed off a few times because of such a situation. Accounts of orders and dispatches getting lost or captured abound throughout military history. I think it’s as possible as anything else that the actual courier of the message might have met his demise soon afterwards in one of the several clashes, including the one at Antietam itself, that took place in the days immediately after Sept. 13, 1862. Unless documentation is finally discovered that conclusively proves who did what and when, this will always remain a mystery.

Douglas’s well-written comment deserves a response. Douglas asks whether there is a definite time established in evidence as to when Lee learned of the missing order. General Lee learned of the missing order during the dark morning hours of September 14, when he received at Hagerstown a message from Stuart at Boonesboro telling him the order was in McClellan’s hands. He made this statement in his own hand when he replied to D.H. Hill’s letter in February 1868. The original of the letter is in the D.H. Hill Papers at the Wilson Library, UNC.

When Stuart retired westward from Frederick on September 12, Fitzhugh’s cavalry was at Westminster making its way westward on a line parallel to Burnside’s line of march. On September 13th, with McClellan in Frederick with the order in his hands, Fitzhugh’s command was some five miles north of the town on the west side of the Monocacy. At 5pm, Pleasonton was informed of the Confederate cavalry’s presence and ordered a force to move toward it. During the late evening and night of September 13th, Fitzhugh moved his force west across South Mountain and the Middletown Valley and arrived at Boonesboro sometime during the 13th-14th. With him was the “citizen of Maryland” who had come to him and whom he escorted to Boonesboro. Who this person was, the record does not expose.

The orders: No, the record does not tell us the circumstances in which Hill obtained Stonewall’s copy. Stonewall, his Adjutant, Dabney, and Hill were married to sisters. This is a fact that has relevance to the situation, as does the fact that Rev. Dr. Ross and Charles Venable were married to sisters. The actors in this play were family related which provides secrecy. While Hill tells us that he did, in fact, receive Stonewall’s copy, he does not tell us how or when; only that, instead of leaving it where it belonged, among his HQ papers, when he was on the Opequon he sent it home to Carolina. It is plain to a trial lawyer that Stonewall provided Hill with the copy to give Hill a defense when he got attacked publicly as the officer who carelessly lost Lee’s HQ copy. Hill and his Adjutant Ratchford state the HQ copy was never presented to Hill’s HQ, and it would have been Ratchford who would know.

The decisive point, from the point of view of evidence, is that the percipient witnesses who ought to know who wrote copies of the order, if any one, at Lee’s HQ, when they were written, to whom exactly were they delivered and how, all claim when asked that they know nothing about it, can’t remember being involved in any way in the process, and yet it was their jobs to be involved in the process. Given the fact, then, that they know nothing the fact-finder must conclude that General Lee, himself, was the witness who handled the process, whatever that process was, and it is most probable, therefore, that what happened is exactly what Lee intended to happen.

“Chilton unquestionably wrote the copy of the order found in the field.” Unquestionably Chilton did not write the copy of the order found in the field. How can it be that the hack civil war crowd is still committed to a fact an idiot can see is not the reality?

Well, “hack” is a pejorative but hard to refrain from in the circumstance. NPS Evans writes, for example: “Lee ordered Robert Hall Chilton, his assistant adjutant general, to write and distribute his orders regarding the army’s movements.” She made the fact up. None of the officers of Lee’s staff, in their writings after the war, acknowledged knowing anything about the order, least of all Chilton who as early as 1867 told Hill he thought the order was written by Taylor and issued to the divisions while the army was still at Leesburg.

Sears, in Landscape turned Red: “During the day of Sept. 9, R.H. Chilton busied himself making copies of order 191.” The man just made the fact up as a romance in his mind.

The acceptance of reality is slow, but it is grudgingly emerging. A recently arrived writer, Alexander Rossino, in his book Their Maryland, hedges the party line with, “The writer of [the] orders, presumably Col. Robert H. Chilton, crossed out the 8 and replaced it with a 9.”

No, not quite. First, with Taylor out of the way, General Lee dictated the text to Charles Marshall and had him label the order 190. Second, he went to A.P. Mason and had him copy the text into Chilton’s letterbook, inserting it in the space of the page that had “Special Order 191” already written in it, in Mason’s hand, making what was originally a two paragraph order into a ten paragraph order. Third, Lee took order 190 to Stonewall who copied the text in his own hand, changing a phrase in the paragraph dealing with Walker. Fourth, Stonewall took his hand-written copy to Dabney and had Dabney make a copy in his hand. Dabney began writing the date 9/10, was corrected by Stonewall, and wrote the date 9/9. Last, Stonewall gave Hill his hand-written copy and gave Ross (or Venable) Dabney’s hand-written copy. On September 13, at Hagerstown, Lee sent 190, signed by Chilton, to Davis at Richmond where it surfaced in 1944 when Bernard Baruch donated it to the Library of Virginia.

In the event anyone is interested in factual reality, let’s examine Sears’ earliest rendition, which he followed with many. His original story was published in 1992, in the Quarterly Journal of Military History.

“It was Lee’s intention, in crossing the Potomac, to draw [the enemy] after him [where] somewhere off to the north and west in the Cumberland Valley, he would maneuver McClellan into a finish fight.” No one can writer sillier crap than this, unless Sears means the “somewhere” is Sharpsburg.

“To clear the way for the march westward, [Lee} had to establish a new line of communication. . . , and to do that he had to dispose of the federal garrisons.” Sears’ sentence is meaningless without an understanding of the purpose of the new line. In his repetitive renditions he labels it “for supply,” the serious student, thinking it through, labels it “for retreat.”

Sears proceeds to make up facts, by assuming that what Charles Marshall wrote after the war, describing the “custom,” was, in fact, what actually occurred in this instance. Sears writes fiction, not fact: “Headquarters busied itself making copies. . . and dispatching them by courier; each was signed `by command of R.E. Lee’ and each was marked confidential, with the name of Chilton. Each was delivered in an envelope to be returned as proof of delivery.”

In fact, the undisputed objective evidence shows, none of the members of Lee’s staff, nor Chilton, admitted after the war having any personal knowledge of who wrote the order, to whom the order was delivered, how it was delivered, or when it was delivered. Taylor, who would be the first person to question, was gone from the scene. Chilton’s post war statements make clear he had no knowledge that, in fact, such an order was actually signed and sent to anyone. Marshall knows nothing. Long knows nothing. Venable knows nothing. Taking them at their word, then, the only persons left to question are Lee and Stonewall. Stonewall was dead, and Lee’s official position, taken in his 1868 letter to Hill, is that he had “no idea how the order got lost.” This scenario would be laughable to trial lawyers operating in the trial court. Boy, would Lee take a beating. Because the lawyers would marshal facts and shove them down his throat.

No one then, and apparently no one now, wants to admit that General Lee planned the happening of the battle, with Stonewall, between Sept 6 and Sept 9. The only thing in the way of its happening, was the necessity to secure a line of retreat.

You and I agree here. Chilton did not write the lost copy of the order. That said, the theory about Dabney is nonsense. Dabney was not even with the ANV in Maryland.

Really? His correspondence with Jackson held by the UVL establishes otherwise, as does the text of the book he published in 1865, this echoed by his son, Charles, after the war. But, hey, I have been at this for thirty years. You? At least you have added intelligence to the subject, as opposed to the “buffs” that hang on the site.

Of the several factual issues the matter of Special Order 191 presents in the trial court, the most difficult for the fact-finder to resolve is the issue of how the Order was created. This is because two of the percipient witnesses made statements which cannot be reconciled without their being cross-examined in the trial court. The first of these witnesses to take a position publicly on the issue was Walter Taylor, who published a book in 1878. In it, he said: “Charles Venable says, ‘One copy was sent to Hill directly from Headquarters [which] was undoubtedly left carelessly by some one at Hill’s headquarters.'” (Eight years later, in 1886, A.L. Long, in his autobiography of Lee, repeated Taylor’s statement of what he claimed Charles Venable said.)

Charles Venable lived to the turn of the Century. Though he spent the post-war years as Chairman of the Department of Mathematics at the University of Virginia at Charlottesville, Venable did not publish any statement concerning his knowledge of the transmission of the Order to Hill’s headquarters. But, he did write am unpublished manuscript of memoir which contains this sentence: “The Order, dictated by General Lee, was copied by Taylor’s brother (Robertson Taylor) and Taylor sent it to the generals of divisions.” Query: Did Venable mean “Taylor sent it” to refer to Walter or to Robertson? (Robertson Taylor survived the war, but he wrote nothing about his war time experiences.)

Venable died in 1900, Taylor in 1916. In 1906, Taylor republished his 1878 memoir of Lee. In his 1906 book, Taylor changed the story, writing this time: “I did not supervise the promulgation of this Order, but Venable always contended that one copy was sent to Hill from General Lee.”

The fact Taylor, in 1906, publicly denied having “supervised the promulgation of the Order” suggests to the trial lawyer that he had become aware of Venable’s unpublished statement that it was “Taylor” who had “sent the Order to the generals of divisions.” The trial lawyer’s mind is pricked, too, by Taylor’ changing his story: In 1878 he told us that Venable said “one copy was sent to Hill directly from headquarters,” but in 1906 he tells us Venable said “one copy was sent to Hill from General Lee.”

The conflict in the evidence these two men provide is a bit amazing, given the fact that the record shows Venable and Taylor corresponded with each other through the years in question, were plainly on friendly terms, and had met each other on several occasions. It does not seem likely, to the trial lawyer’s mind, that the two men did not at some point discuss what the story line would be, that is get their story straight. Since it is plain that they did not, the inference arises neither man knew what actual involvement the other had in “supervising” the “promulgation” of the Order, much less knew whether the Order was sent to Hill “from Headquarters” or sent to Hill “from General Lee.”

Finally, as to the matter of the sequence in which copies were made, in the two years that have passed since the original remark above was posted, investigation has been continuing, and it suggests a revision is required. First, it appears that General Lee dictated the text of the Order to an unknown clerk. The clerk’s handwriting is recognized by reference to the Headquarter letterbooks. The clerk’s handwriting accounts for the copy marked Special Order 190. Second, it appears likely that A.P. Mason used Special Order 190 to copy the Order’s text into Chilton’s letterbook, adding the eight paragraphs to the two paragraph text of the original Special Order 191. Third, it appears likely that General Lee then gave Special Order 190 to Stonewall Jackson who copied the text in his own hand, changing in the process the syntax of the sentence in paragraph VI. Fourth, some one copied the text of Jackson’s copy as he had written it, and this copy was dropped in the farm field as Barton Mitchell was stacking arms. Presently, it is reasonable to look seriously at Jackson’s Adjutant, William L. Jackson as the writer of the copy Mitchell picked up from the ground.

Mr. Klein cites four sources he suggests you consider. The first two are two authors who made a good living selling themselves to the popular audience. But is this audience really the popular audience? Are the people behind this curtain actually interested in establishing the objective truth of our civil war? What does Sears and McPherson offer to the investigation that is meaningful? The reality of the civil war is too close to us; it will take another hundred years to shed the silliness of romance and study deeply the original record, establish by a standard of review, what actually this person did and this time and why. So much detail, means so many years digging, no way out of the work.

The next source is the Battlefield Trust” quoting the text of the lost order.

The last source, is my piece on the issue, which, with the deletion of my website, should be deleted from the web. I am just one of thousands of intense trial lawyers who practice across the nation, selling their cases to juries in the box, under the supervision of the court. General Lee’s side was down and out in September 1862. All that was left, was the coup de grace. When they went in to it, they knew what they were doing; they meant to go down hard.

All the enemy had to do, is drop the final axe. With the lost order General Lee gave his country, his Government, his people–two more years of existence in the East. A great American soldier, Eisenhower understood.

When it comes to the Maryland Campaign, I like “Taken at the Flood” by Joseph Harsh.

The website joeryancivilwar has been deleted from the web. The article, Special Order 191: Ruse of War can be read here. https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/fhhun1fjekf30h14aelkb/RUSEWORD.LEE.doc-rev.doc?dl=0&rlkey=opdoe1eg764e3e33nrkadpa4h

I recently obtained from the University of Virginia, the text of the memoir Charles Venable wrote shortly after the war. The manuscript is in his hand and, in relevant part, it reads:

“The order, a dictation by General Lee, was copied carefully in the Adjutant’s tent by Col. Taylor’s aid and brother in the camp at Frederick City and sent out to the divisions by Col. Taylor to commanders and divisions who were concerned. The couriers in every case brought back receipts. General Jackson sent a separate one in his own hand to Hill who had already dropped the one sent from army HQ on the floor of his tent which was picked up by a federal officer and thus reached McClellan’s hands.” (pp 60-61.)

When Venable wrote this text, nothing had been published publicly by any percipient witness stating the circumstances of how the order was prepared and lost. This is the first reference to be found in the record, of Taylor’s brother, Richard Cornelius Taylor (VMI 1854), being at Frederick.

We start with the statement–“The order, a dictation by General Lee, was carefully copied.” Venable does not tell us who was taking Lee’s dictation. Whoever the person was (assume it was Jackson) Venable tells us the order as dictated by Lee was copied by Taylor’s brother, but Taylor, in his 1878 book, does not tell us his brother was at Frederick, telling us only that he, Taylor, had no idea how the order was created, because he left Frederick on September 9 and went to Virginia.

What cannot be ruled out is that, in Walter Taylor’s absence, his brother Richard “copied” the text of Stonewall’s draft of the order, dictated to him by Lee, and this copy, apparently with additional copies, was sent to Hill among others, and that, on the basis of some unknown fact, Venable claims Hill dropped this order in his tent which found its way to McClellan.

What this scenario tells us, is that, when he wrote his memoir, he did not know how the order was found. It appears Pollard, in his 1867 Lost Cause book got the lost in tent story from Venable, or Venable read Pollard’s book and got the tent story from him.

One now searches for authentic handwriting examples of Richard C. Taylor’s handwriting to compare to the Library of Congress copy of the order which may, or may not be, the actual document handed to McClellan, as the chain of custody from 1862 to 1925 is not established.

Nowhere in his memoir does Venable inform us how he knows that (1) Hill dropped the HQ copy in his tent, and (2) that Hill had given the supposed courier a receipt which was returned to HQ.

Had Venable written, “I sent the courier with the HQ order copy to Hill and the courier came back to me with a receipt signed by Hill,” we would have a distinctly different situation in the trial court than we have with what Venable has actually written, a statement unsupported by fact is not admissible in evidence.

What we see in the trial court is this: General Lee and Stonewall drafted the language of the order, this done in Stonewall’s hand. Lee gave Stonewall’s copy to Maj. Taylor, who was not a member of the staff, a visitor, a guy standing by, and told him to make a copy, and put at the bottom, cc Hill.

Lee took back Stonewall’s copy and Taylor’s copy. He gave Stonewall’s copy to Marshall and told him to make a copy, which, later he sent to Davis.

Any other copies made at HQ, though there is no evidence of such, were copied from Marshall’s copy before it was sent to Davis.

Venable took Taylor’s copy to Mrs. Ross. Stonewall gave his to Hill.

In the trial court, this theory is supported by admissible evidence, it is for the jury to decide whether it has the more convincing force.

Major Richard C. Taylor served as captain of “The Independent Grays,” in 1861. This unit became attached to the 6th Virginia Regiment of Mahone’s brigade in June 1862, as Company H.. In 1861, on station at Norfolk, it appears Co. H was an artillery battalion, but by the time Mahone’s brigade, Anderson’s division, entered Maryland in September 1862, it was infantry, though this is not clear.

In June 1862, Taylor was replaced by election as captain of the company though he retained his rank. What role he played in the company during September1862 the record does not presently disclose. What can be said as a probability is that Taylor was present in Maryland as a member of the 6th Virginia Regiment and therefore could have been with his brother at Lee’s headquarters.

The fact that Venable named Richard C. Taylor in his unpublished memoir, as the person who copied Lee’s dictated first draft is difficult to digest. Why would Venable reveal the name, as doing so results in the finger being pointed at Taylor. The manuscript copy of the memoir purports to have been completed by 1898, long after the publication of Walter Taylor and A.L. Long’s books, and some 18 years before Richard C. Taylor died. One must consider the fact neither Taylor would have appreciated Venable “outing” Richard during his life. But how did Venable know this? He does not say, so we have no factual basis that justifies accepting his uncorroborated statement as true. Still, it makes sense that Lee would use someone to write Hill’s copy who was not part of the HQ staff, someone a stranger to it, yet someone Lee could count on, to keep his mouth shut. Who better to foot the bill that Walter Taylor’s brother?

Had he in fact copied i, Richard C. Taylor would not have known about the loss of the order addressed to Hill, until the publication of McClellan’s report of operations in 1864, and it was not until Pollard’s book was published in 1866 that the business of Hill dropping it was public knowledge. If he was involved, he would have asked his brother what had happened.

Ultimately the question who wrote Hill’s copy cannot be resolved because neither Richard Taylor nor Dabney’s handwriting appears to match, and we cannot establish in evidence the chain of custody of McClellan’s copy. It may be that McClellan’s chief of Staff, Marcy, took the order after McClellan read it and had a copy made which was used to transmit the text to Pleasonton by telegraph and a copy was made by the telegrapher who received the transmission and given to Pleasonton. What may have ended up as part of McClellan’s “papers” which he took away with him, when he was relieved of command, was a copy made by Marcy’s involvement, and the original may have eventually sold into a private collection.

During his lifetime, McClellan replied to a D.H. Hill letter, saying he wold look in his papers for the order but no record exists to show the result. McClellan died in 1885. A wealthy friend named Prince acted as his Executor and, when McClellan’s son caused his fathers papers to be delivered to the Library of Congress, in 1925, among them was found an envelope on which Prince had written: “This is the original order delivered to McClellan.” But we have no basis to know what Prince was relying upon to make this statement. He could have assumed a fact not in evidence.

Still, the fact Venable actually named Walter Taylor’s brother as a copier of Lee’s dictated draft of the order carries with it by inference some credibility, as we can conclude it unlikely a person in Venable’s circumstances would have pointed the finger at Taylor without some reasonable basis for thinking Taylor had been a copier. And, if anyone, of the staff should have known, it would be Venable.

Venable would have known disclosing Richard would cause some embarrassment to Richard who now would have to explain his involvement, or deny it. The fact can explain why Venable did not publish his memoirs, realizing he could not “out” Richard.

It’s September 13, 2022, and the absence of comments makes plain no one is interested in who lost the order, except a few “buffs” with time on their hands. But, today, the order was found, and Ryan’s latest research has finally revealed who probably wrote it: E.F. Paxton, Jackson’s Adjutant.

Actually, on This Day in History, mentions that the Lost Order was found by Union troops.

If you visit the Best Farm, the site where the order were lost, you’ll find that it’s picnic worthy, and that it’s unclear where exactly it was that the cigars and orders were found. You’ll also find that the walls of urban sprawl are closing in on the lovely 274 acres of that once-748-acre pivotal site, a part of the Monocacy Battlefield.

Henry I agree. Some believe the spot to be underneath one of the stores of a shopping center.

“Alex Rossino says:

September 14, 2022 at 9:55 AM

You and I agree here. Chilton did not write the lost copy of the order. That said, the theory about Dabney is nonsense. Dabney was not even with the ANV in Maryland.”

It appears you may be correct in your statement that Dabney was not at Frederick, though I have not found direct evidence of the fact. From Dabney’s letters of the time, one can infer that, in about late July 1862, he became sick with “camp fever” and it seems the sickness caused him to leave his position at some point. This fact may explain why E.F. Paxton was appointed about this time as “Assistant Adjutant General.” Paxton, by his letters, establishes the fact that he was at Frederick, but a comparison of his handwriting with McClellan’s copy does not appear to be a match.

Between Dabney’s handwriting and Paxton’s, Dabney’s seems closer to a match than Paxton’s but still not close enough to call. If it is a match, then Dabney was at Frederick.

What is a fact is that, by letter, Jackson accepted Dabney’s resignation as his “Adjutant General” on September 23, 1862 at Bunker Hill.

These facts force one to move on, in the search for a match, from Dabney and Paxton, to who? The focus shifts to Joseph G. Morrison, Jackson’s, as well as D.H.Hill’s, brother-in-law. In 1868 Morrison appeared before a Notary and, according to the Notary, said, under oath, that he had seen Jackson’s copy and recognized the handwriting as Jackson’s. Morrison made no statement about his personal involvement in the creation or transmission of any copy of the order to Hill, merely stating that, given custom and practice, “it was proper” that an order of Lee’s pass through Jackson to Hill. And, on the margin of the actual copy, Morrison appears to have written at some point in time: “I certify that. . . [it] is Jackson’s handwriting.”

Dabney’s son’s memorandum which states “it appears my father sent Hill Jackson’s copy,” therefore, seems not to make sense. If his father was not at Frederick, the son may have meant he thought his father sent Jackson’s copy to Hill at sometime after the campaign was over.

Hill, in his statements, does not actually state when exactly it was he received the document, or from whom. In his 1868 statement Hill states only this: “[I] have in my possession now, a copy. . . which is in Jackson’s own hand. . . I carried it in my pocket. . . (At Chattanooga) I wrote home that the copy could be found among my papers, having been sent home by a private hand while we were camped on the Opequon.” From Hill’s statement the fact-finder cannot conclude when and where Hill received in his hand Jackson’s copy. All that can be reasonably concluded, is that Hill had the copy in his hand no later than his presence at Bunker Hill, and that someone–Morrison?–carried it home to North Carolina.

Dabney was related to the Morrisons and through them connected to both Jackson and Hill. If, as his son states, Dabney gave Jackson’s copy to Hill where and when did he give it to him? If Hill received Jackson’s copy in his hand while at Frederick, why didn’t Hill state the fact plainly in his piece. Why make the issue ambiguous?

Whoever created the document Mitchell found, the objective evidence makes plain he didn’t find i by accident. Where exactly Hill’s division camped at Frederick is of little relevance to the case of the “lost order.”

To sum the objective evidence up:

1. Taylor states publicly he had no involvement in the “promulgation” of the order.

2. Venable states privately Taylor’s brother copied the original that Lee had dictated to someone, and Taylor send copies to generals in the field.

3. Marshall states he knows nothing about the order, yet he wrote a copy in his hand.

4. Hill’s Adjutant, Ratchford, states no copy of the order came from Lee’s headquarters. He states nothing about receiving Jackson’s copy.

5. Jackson and Paxton died in May 1863.

6. Dabney appears to have been gone from his position in all or part of September. He wrote three books about Jackson and the war, but states nothing about his involvement or noninvolvement in the promulgation of the order.

7. Dabney’s son states “it appears his father gave Jackson’s copy to Hill.” If so, when? Where?

8. General Lee states he has no knowledge how the order was lost, but that he thought it proper a “copy be sent to Hill by the Adjutant General.”

9. Gen Cooper was, in fact, “the Adjutant General.” Chilton was Asst. Adj. Gen.

10.The copy of Order 191 that Chilton signed was transmitted to Gen. Cooper..

11. The copy of Order “190” written by Marshall was sent to Davis.

12. The text of the two documents signed by Chilton were consolidated as one by A.P. Mason writing them into Chilton’s letter book.

13. McClellan’s chief of staff, Marcy, had a telegrapher send the text of the order by Morse Code to a telegrapher at Braddock’s Gap, to give to Pleasonton.

14. Some twenty years after McClellan’s death his son gave his papers to the Library of Congress. Among the papers is a statement by McClellan’s “literary Executor” that “this is the original order received by McClellan.”

These facts are established by reference to the original documents to be found in the depositories and the direct statements made by the witnesses in their life times, as opposed to being based on what this novelist published last month, or last year, or twenty years ago.

What most reasonable persons would conclude from the evidence, in the trial court at least, is that it is hardly probable that none of the percipient witnesses, who should know, know nothing of how the order was created, copied, and “promulgated.” Which means they are hiding the ball, that one or more of them are lying. Which means whatever happened, it did not happen by accident but by design.

And then we have the end result: a soldier sees a package of fresh cigars at his feet, which cannot possibly have been there where he found it for three days through a 24 hour rain storm, and, bingo, the enemy does exactly the opposite of what he would have done but for the order being handed him.

So, do you have an example of Joseph G. Morrison’s handwriting to share?

To the very few of you who are actually interested in this, here it is, thirty years later, still digging, since the judge has not called me to produce the first witness, and I find a thirty-four page biography privately published by Joseph Morrison’s son, in 1955. No one has found this, the sole copy surviving is at the Wilson Library; and what does it tell us. It tells us that Morrison was a part owner in the magazine The Land We Love, and that, when Hill published his piece about “The Lost Dispatch,” and sent a copy to Lee and Lee responded with his letter, Morrison the next month had sold out to Hill and took a ship to California where he remained until General Lee died, in 1870, and then he returned to North Carolina. We trial lawyers, the ones that actually have made our living trying case to verdicts in court, read this and suddenly we are vibrating. We do not accept coincidence. We have questions for Joe, which is why he bailed. The biography contains quotes from letters Joe wrote home in 1862. Find a sample and compare it to McClellan’s copy.

I enjoyed the bantering back and forth with facts, can any claim to be in evidence? If Lee allowed this subterfuge, that is one consideration. If the young courier lost them, who was claimed to be a smoker, he appears to be effeminate in nature with his mentor. Any evidence of a relationship?