Sailor and an Artist – Robert Weir of the USS Richmond

Aboard the USS Richmond, floating just off Pensacola Bay, Third Engineer Robert F. Weir sat in his “little cosey, hot, office,” hard at work penning letters to his wife and composing sketches for Harpers Weekly. These letters, accompanied by doodles of ships and forts, reveal the inner lives and dramas of sailors serving on blockade duty during the Civil War.[1]

Born January 12, 1836 in West Point, New York to Robert Walter Weir, acclaimed painter and drawing professor at West Point, and Louisa Ferguson Weir, Robert’s upbringing influenced his future reputation as an amateur artist. Instead of becoming a painter like his two brothers (John and Julian Weir), Robert ran away to sea at the age of 19 to begin his life as a sailor aboard a whaling vessel. On August 25, 1862, Robert enlisted in the Union Navy as a third assistant engineer and was assigned to the sloop-of-war USS Richmond, which had been part of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron under Flag Officer David G. Farragut since early March. Robert missed out on the battle of New Orleans in April, but he didn’t miss the chance to marry Anna Chadwick on September 16 before shipping south. For the next three years, as Richmond blockaded southern ports, Robert remained in constant communication with Anna – whom he called “Daisy” – via letters sent through New Orleans.[2]

The Navy Yard at Pensacola was of key importance to the blockading efforts in the Gulf of Mexico. Until the fall of Pensacola, Ship Island off Mississippi had been the main depot for resupply and repairs. Despite the extensive damage to the navy yard after the Confederate evacuation, it was recommended that Pensacola become another repair station and double as a hospital.[3] Pensacola Navy Yard was rebuilt and became a favorable depot for the West Gulf Blockading Squadron. Therefore, it is no surprise that many of Robert’s letters were written off Pensacola Bay as Richmond stopped for coal or repairs, giving him plenty of time to explore the town.

On a few trips in the fall of 1862, Robert wrote home about the famous white sand that “affects the eyes like newly fallen snow in the bright Sunshine – and I can answer that it is very hard travelling about in it.” He also reported that “Fort McRee is a mass of ruins internally,” and remarked upon the houses in the “inhabited Secesh town” with its “gardens filled with flowers & orange trees… laden down with their golden fruit.” Robert wrote about the cold reception of Pensacola “Secesh ladies” and how they “would draw their dresses close to them while passing & give my uniform a wide berth.” In their downtime, whether in Pensacola or patrolling off Mobile Bay, Robert and his fellow sailors embarked on fishing and hunting excursions, but the sight of any “formidable looking object, or any diabolical intention on the part of the Rebels coming down the Channel – they still signalize the ships & then pull for their lifes for their respective ships.” And, like many nineteenth century letters, Robert shared about the weather, noting that Southern summers were “so excessively warm that it seems to take the energy out of us all.”[4]

Alongside his stories of the South, Robert was wonderfully candid about life onboard the Richmond. He wrote Anna, “there is always a great deal to be done in our department,” including drills and daily duties such as standing watch, making repairs, and ensuring that the steam engines were in perfect running order. The busy days were a relief to Robert as he was “never so contented as when I have plenty to do.” One job involved recording the “Steam log” where he noted the “consumption of coal, oil, waste, materials of all kinds connected with the Engineer Dept – pressure of Steam Revolutions per Min, saturation of water in boilers & &c – state of weather, course of wind &c.” Apart from duties, Robert shared his frank opinions of the men with whom he worked. Drama that pervaded army life was shared by navy men, as little “affairs” proved to “make it unpleasant for us” leading Robert to make the remark, “I do not wonder that the majority of seafaring men are such worthless idle fellows.” Even in the twilight days of the war, Robert sent home a scathing criticism of the war department, writing, “How often have I been filled with disgust by the same performances that I have witnessed in the Army & Navy – but the Navy in my eyes is proverbial for slow brain, dull understanding & old fogyism generally.”[5]

Aside from the tasks of keeping the ship afloat and dodging incompetent coworkers, Robert found solace in his office where he could take the time to write letters to his wife, sketch, read, and study for examinations, though “on board ship is the last place to study in.” Robert was formally tested in his knowledge of engineering principles such as “Saturations of different kinds of water in boilers – Expansion of Steam – how much water & fuel is expended in generating such quantities of steam in different kinds of boilers.” Even in the winter when “heated solid shot answer the place of stoves for our quarters” Robert’s pen was constantly at work on letters and sketches for the amusement of his wife.[6]

The predominant theme in many of Robert’s letters was a preoccupation with the wellbeing of his “Daisy.” Through his letters, it is alluded that she did not always have the best of health. He continually admonished her to “Do all you can My darling Wife to promote your health” and “take the utmost care of your health & not expose your self in any way.” He inquired about her weight and vigor, the tone and language insinuating that her health was precarious. This may give hint as to why the couple remained childless. Regardless, Anna remained a constant in his thoughts, leading Robert to think, “would Daisy like me to go, or do so & so, be it right or wrong” and to lament “I do not think this abominable life at sea is one calculated to make a good husband.” To Robert, Anna was his safe harbor and told her, “the remembrance of your loveliness & purity is a sufficient spur to enable your husband to overcome many a tough obstacle.” At the close of every note, he begged his wife for more letters and kept track of those she had sent – numbering over a hundred. In a time when mail relieved monotony, Robert treasured each word from Anna, going as far as to say, “If I do not get a letter from My dearest Wife very soon I shall get sick or blow up something with an infernal Machine.”[7]

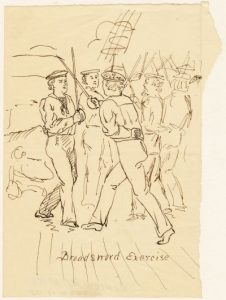

Robert’s lasting mark was undoubtedly his many sketches, several of which were published in Harper’s Weekly. These sketches, housed with the Mariners’ Museum Library’s Robert Weir Papers in Newport News, Virginia, vividly illustrate the experiences of blockade duty. While Robert believed Harper’s Weekly would “not think them worth receiving,” these drawings showed the folks back home the reality of navy life and celebrated Union victories, such as during the Battle of Mobile Bay in August of 1864. Robert was wounded in the attack on Port Hudson in March of 1863, when a piece of shell struck him in the abdomen, which caused him chronic health issues following the war. After taking time to recover, he returned to blockade duty with Richmond that winter. He resigned from the navy on July 10, 1865, then rushed home to be with Anna. His career as an artist and engineer continued, as he submitted more sketches to Harper’s Weekly and became a civil engineer for the Union Subway Construction Company of New York. He was denied disability for his war wounds in 1897, and would die of heart troubles on January 17, 1905, just five days after his 69th birthday. He was interred at Oakwood Cemetery in Troy, New York, and Anna received a widow’s pension until her death in 1910.[8]

By April of 1865, the Union Navy captured or destroyed 1,504 Confederate vessels that tried to cross the 3,000-mile blockade around the South’s 189 inlets.[9] While it is disputable how much damage the Union blockade actually inflicted upon Confederate commerce and morale during the Civil War, the lives and experiences of the sailors who patrolled the coastal waters are vital parts of the war narrative, whether they be found in letters or in sketches.

Endnotes

[1] Robert to Anna, October 30, 1862, Pearce Civil War Collection, Pearce Collections Museum, Navarro College, Corsicana, Texas (hereafter referred to PCWM)

[2] Gary McQuarrie, “Robert Fulton Weir: Sailor-‘Artist’ for Harper’s,” (New Hope, PA, Civil War Navy – The Magazine, Spring 2020), pp. 43-49

[3] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume 18, pp. 481-482; Ibid, Volume 19, pp. 163-164

[4] Robert to Anna, October 19, 1862, October 27, 1862, November 27, 1862, November 11, 1863, November 19, 1864, July 13, 1864, PCWM

[5] Robert to Anna, December 17, 1863, Civil War Collection, University of West Florida Historic Trust Archives, Pensacola, Florida; Robert to Anna, October 19, 1862, October 30, 1862, January 8, 1864, April 1, 1865, PCWM

[6] Robert to Anna, October 28, 1863, October 30, 1862, January 13, 1864, PCWM

[7] Robert to Anna, November 11, 1863, November 27, 1862, October 28, 1863, October 30, 1862, July 20, 1864, PCWM

[8] Robert to Anna, January 8, 1864; McQuarrie, pp. 44, 48-49

[9] William N. Still Jr., “A Naval Sieve: The Union Blockade in the Civil War,” (Naval War College Review, Vol. 36, No. 3, May-June 1983), p. 39

Well written article, presenting much new information. A real joy to read. The only disappointment: Robert Fulton Weir was not assigned to USS Richmond a year earlier, when USS Richmond and USS Niagara took part in leveling CSA-controlled Fort McRee, just west of Fort Pickens.

Good show on this article. That is so true that soldiers counted every letter they received from every person. Letters meant so much to them.