Advancing To Strasburg: Union Generals See What They Want To See In The Shenandoah Valley

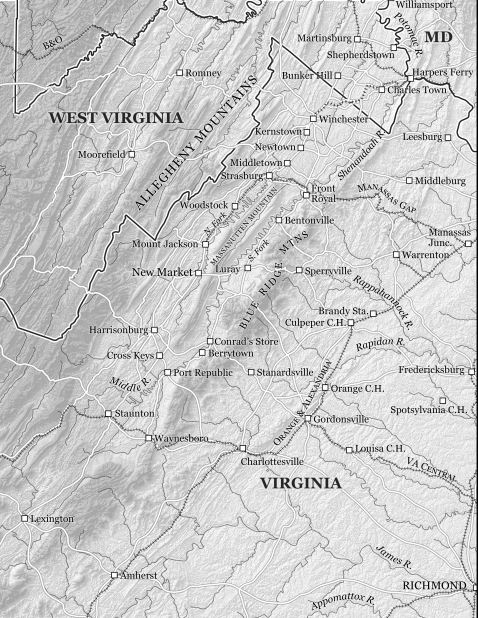

In the March 18, 1862, edition of the Staunton Spectator, residents of the middle Shenandoah Valley read about the Confederates’ evacuation of Winchester and the Union army’s arrival in that same town. Then, the early reporting of new Federal movements began: “On the afternoon of Wednesday, General Shields’ column advanced towards Newtown, but were met and driven into Winchester by Colonel Ashby’s command. On the same day, General Jackson marched to Cedar Creek, on the Valley turnpike, sixteen miles from Winchester and two from Strasburg, where he was encamped up to Thursday night.”[i] Over the next days, Confederate General “Stonewall” Jackson took his small force further up the Valley (moving south), leaving his cavalrymen to guard his rear and continue delaying their enemy.

Meanwhile, the Union generals at Winchester wanted to know how far Jackson had retreated. George McClellan had started begging for more troops to take to the Peninsula for his grand advance on Richmond? Could any troops be spared from the Valley? That depended on how far Jackson had retreated. General Banks told General Williams. General Williams tasked General James Shields to find out. On March 17, Shields ordered two companies of the 4th Ohio Infantry and some detached cavalry to head south under Colonel John Mason’s command, scouting the Valley Pike and the country roads as far as Strasburg.

Colonel Mason’s regiment — the 4th Ohio — had been split and sent to various parts of the lower Shenandoah Valley as pickets or provost guards.[ii] It was a surprisingly small force if the Yankees actually thought they would meet, and before long, Mason got permission to take more troops on his expedition. The 8th Ohio, and 7th Indiana Infantry Regiments joined the previously assembled cavalry and 4th Ohio companies and their mission morphed to operate with the rest of Shield’s division (approximately 8,500 strong) in a “pincher” style movement to catch Colonel Turner Ashby and the Confederate cavalry around Middletown.[iii]

David Hunter Strother, a local Virginian who remained loyal to the Union, accompanied Mason’s reconnaissance and wrote in his diary on March 18: “Ashby was reported to be at Middletown. When within a few miles of this place, as we stood upon a height locating the points of the surrounding country, Mason’s adjutant rode up informing us that his force had got into Middletown and that Ashby was in sight between them and Strasburg.”[iv] The idea to catch the Confederate cavalry commander at Middletown started falling apart. “I knew that a gull would stand as good a chance to catch a fox, as our force to catch Ashby,” Strother wrote.[v]

Ashby withdrew further south, leaving Middletown about an hour ahead of the Union troops.[vi] According to Strother, the Union soldiers discovered “a grand column of smoke…rising toward Strasburg. This we were informed was the turnpike bridge over Cedar Creek.”[vii] On the high ground on the Strasburg side, Ashby fired off a couple of cannons, delaying the Union troops until General Shields arrived and organized an advance across the creek. However, he decided to delay and not cross at twilight.[viii]

On March 19, Union troops crossed Cedar Creek, and “the General expressed his annoyance that he should have been stopped by such a trifling obstacle, it being fordable everywhere, even for the infantry.”[ix] Meanwhile, the Confederates had already fallen back. Artillery on both sides attempted to fire as Shields pursued Ashby several miles south of Strasburg. Deciding he had gone as far as his orders had dictated, Shields pulled his blue-coated troops back to Strasburg and secure his supply line to Winchester.

An officer in the 8th Ohio, who had had enough of the Confederate artillery (Chew’s battery) and Ashby’s defense, raised no objections to returning to Strasburg, saying, “This Ashby was the terror and wizard of the Shenandoah.”[x] Indeed, Ashby’s delaying tactics and defense had delayed and annoyed Shields and started to build some fear of the unknown in the minds of Union soldiers in the Shenandoah Valley. Ultimately, Ashby did not prevent Shield’s reconnaissance mission; Shields reached Strasburg and confirmed that Jackson’s army was further south.

After ascertaining that Jackson was not at Strasburg, Shields turned his command around…and marched back to Winchester on March 20, forcing his men to cover 22 miles in one day in miserable, spotty rain. (In the coming weeks, “Stonewall” Jackson would become infamous for forced marches like this.) Shields arrived in Winchester and triumphantly announced to General Banks that Jackson was gone. Colonel Mason captured the mood and belief of the Federal officers: “Jackson was off a long distance and that all we would have to do, until we had got things in readiness for an advance, would be to picket well in front.” They concluded that Jackson had gone as far south as Mount Jackson, maybe further. As proof of their confidence, the generals prepared to send some of their force out of the Valley, Shields camped his division on the north side of Winchester, and the wagon trains remained parked on the south side of the city.[xi]

Jackson had retreated to the area of Mount Jackson and encamped at “Camp Buchanan,” letting his army rest and recovery from illness that had swept the ranks after the soldier drank contaminated water during their retreat.[xii] Ashby watched, delayed, and skirmished with Shields, keeping Jackson informed. At first, Ashby reported that the Union advance might be aimed at chasing Jackson as far as Staunton, but he quickly reported Shield’s return to Winchester. Stonewall concluded that his enemy felt confident and safe…and he correctly guessed that Banks planned to send a detachment of troops to join General McClellan and the Army of the Potomac’s advance toward Richmond, via the Virginia Peninsula.

General Joseph E. Johnston corresponded with Jackson, advising him on March 19: “Would not your presence with your troops nearer Winchester prevent the enemy from diminishing his force there? It is important to keep that army in the Valley, and that it should not reinforce McClellan. Do try to prevent it by getting and keeping as near as prudence will permit.”[xiii]

The brief Union reconnaissance through Middletown and Strasburg, following by a quick return to Winchester revealed more of the Federal plans than they anticipated. The stage was set. Jackson had received Johnston’s message. Stonewall’s motivation to return and liberate Winchester — or at least annoy the Yankees – was fueled by his frustration had abandoning the town in the first place. On March 22, 1862, Confederate troops broke camp, formed columns, and started marching north…back toward Winchester.

Sources:

[i] Staunton Spectator, Evacuation of Winchester, March 18, 1862. (Accessed via Newspapers.com)

[ii] William Kepler, History of the three months’ and three years’ service from April 16th, 1861, to June 22d, 1864, of the Fourth Regiment Ohio Volunteer Infantry in the war for the Union (1886) Page 59. Accessed via archive.org https://archive.org/details/historyofthreemo00kepl/page/n141/mode/2up?ref=ol

[iii] Peter Cozzen, Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson’s Valley Campaign (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008). Page 149.

[iv] David Hunter Strother, edited by Cecil D. Eby, Jr., A Virginia Yankee in the Civil War: The Diaries of David Hunter Strother (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1961). Page 16.

[v] Ibid., Page 16.

[vi] Peter Cozzen, Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson’s Valley Campaign (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008). Page 149.

[vii] David Hunter Strother, edited by Cecil D. Eby, Jr., A Virginia Yankee in the Civil War: The Diaries of David Hunter Strother (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1961). Page 16.

[viii] Ibid., Page 16-17.

[ix] Ibid., Page 17.

[x] Peter Cozzen, Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson’s Valley Campaign (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008). Page 151

[xi] Ibid., Page 152.

[xii] Ibid., Page 144-145.

[xiii] Ibid., Page 153.

Fun reading because today(March 19,2022) I coincidentally visited the Cedar Creek battlefield and drove portions of the Valley Pike.