Morgan’s Magnificent March from Cumberland Gap

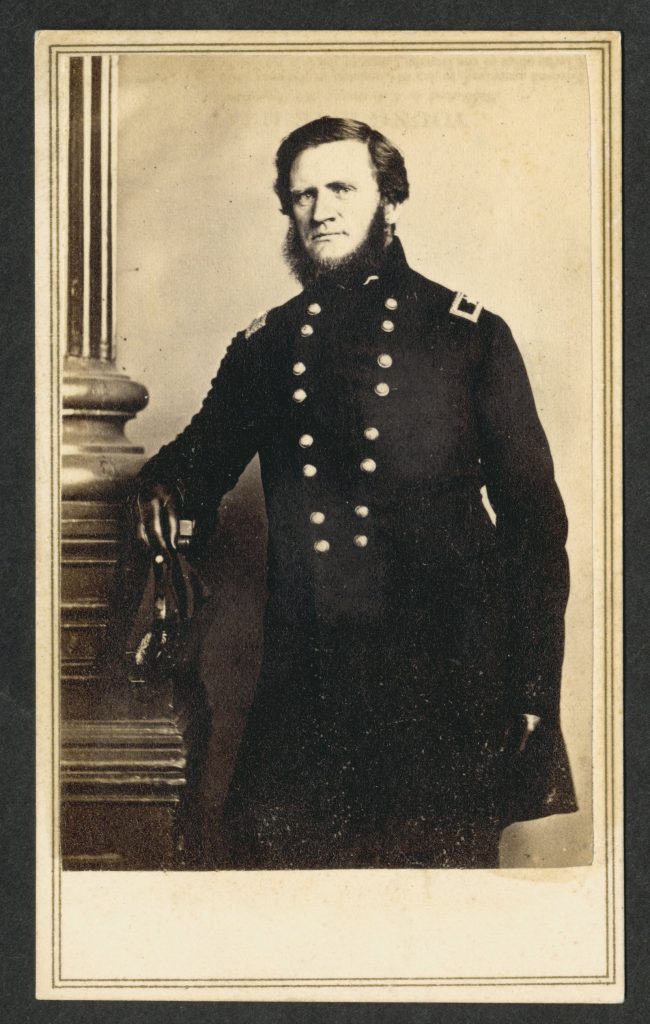

From his perch behind miles of stout defenses in Cumberland Gap, Brig. Gen. George W. Morgan could look daily into his enemy’s camp in front of him. Strangely though, Morgan had more to worry about beyond the enemy in front of him. Instead, during the Confederate movement into Kentucky spearheaded by Maj. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith’s Provisional Army of Kentucky, Smith skirted most of his army around the impressive defenses Morgan’s men constructed and held and left only one division to monitor Morgan’s force.

For a month, George Morgan and Carter Stevenson—Smith’s detached division commander—stared at one another. Except for small skirmishes, neither tested the other’s position. Soon, however, something had to give. The rest of Smith’s army cut off Morgan’s supply line to Lexington, Kentucky—the Wilderness Road. Cumberland Gap provided hardly any subsistence for Morgan’s 8,000 men to eat and they were already living on half rations. Trapped between two enemy forces, Morgan realized he could not remain at Cumberland Gap much longer. On September 14, Morgan’s subordinates suggested an evacuation of their position. The general sided with them and preparations began.

Over a span of two days, soldiers gathered supplies and loaded them into wagons. Artillerymen prepared to take 32 guns along the march, though four were unceremoniously dumped over the mountainside. Then, the Federals booby-trapped their position and the gap. They set mines to destroy their depots. Explosives were placed that, once triggered, cascaded tons of rock downward to blockade the gap and prevent a Confederate pursuit. At 8 p.m. on September 17, Morgan’s march commenced. The next morning, with the enemy unaware of the Federal withdrawal, engineers ignited their planted explosives, which turned the former position into “a volcano on fire, and from time to time after dawn we heard the explosion of mines, shells, or grenades,” recalled Morgan.

Though Morgan’s men caught Stevenson ignorant of the evacuation, the hard part of the journey had only just begun. Two hundred miles lay between Morgan’s division and the friendly confines of Ohio. To make matters worse, Kirby Smith’s army sat on his most direct route. Thus, Morgan’s column had to rely on rough, mountainous roads as his avenue of escape. Morgan completed his homework prior to this march, sketching the route and gathering information from locals along the way. Ironically, the locals told Morgan that his attempt at using these roads to march to Ohio was nearly impossible. Morgan continued on nonetheless. He had no other option.

Despite the hazards and perceived issues, Morgan’s men completed the early days of the march with few issues. They still outpaced the enemy to their rear and received little trouble from that direction. Once Morgan’s force reached Proctor on the Kentucky River, a town about halfway between Morgan’s starting point and his end goal, their luck began to change. The Federals passed over the river undisputed but the terrain and nature started taking its toll on the men. Drinking water was so scarce that “our tongues were parched with thirst,” recalled one Union soldier. “When at length water was obtained in the horse tracks on a low, flat piece of ground, it was fought for by us like so many wolves.” Food proved to be as valuable of a commodity as water; some troops marched 48 hours without anything to eat.

On September 25, the column arrived in Hazel Green, where Morgan granted his men a well-deserved day’s rest. Upon setting out the next day, John Hunt Morgan’s Confederate cavalry liberated beef from the rear of Morgan’s column, meaning no fresh meat for the Federals. Humphrey Marshall’s Confederates also took up the pursuit. At West Liberty, Morgan allowed two more days of rest and a chance for his men to lighten their loads even more. Bonfires popped up around the Federal camps and consumed anything that was not vital to the marching soldiers. While necessary, the delay gave Morgan’s Confederates time to race in front of the Union column.

John Hunt Morgan’s cavalry went from nipping at the heels of the marching Federals to serving as human speedbumps to impede the enemy’s escape. They felled trees and moved rocks to block roads and passages. Ax and shovel-wielding Federals either cleared the blockades or cleared roads around them. George Morgan’s march slowed to a crawl. Persistence paid off. Kirby Smith recognized Morgan could not stop the Federal column and called off the pursuit.

On October 3, the van of Morgan’s division reached the Ohio River and yelled its name in celebration of the incredible ordeal they endured and the feat they accomplished. Overall, Morgan’s march covered 219 miles in 16 days along inhospitable terrain and roads not meant for an army to use. Nonetheless, at the loss of only 80 men, Morgan extricated his command from one precarious place after another and reached the safety of the Ohio River on near empty stomachs. Few marches in the Civil War rivaled what George Washington Morgan’s Seventh Division completed from September 17 to October 3, 1862.

This is an excellent summary of one of the great marches in American military history. I devote an entire chapter to this story in my Perryville book.

I used your book to help write this. Thanks for all the great information!

Thanks for reporting a story completely unknown to me before Mr. Pawlak’s column.