On The March: The Cadets’ Road to New Market

Adapted from Chapter 4 of Call Out The Cadets: The Battle of New Market

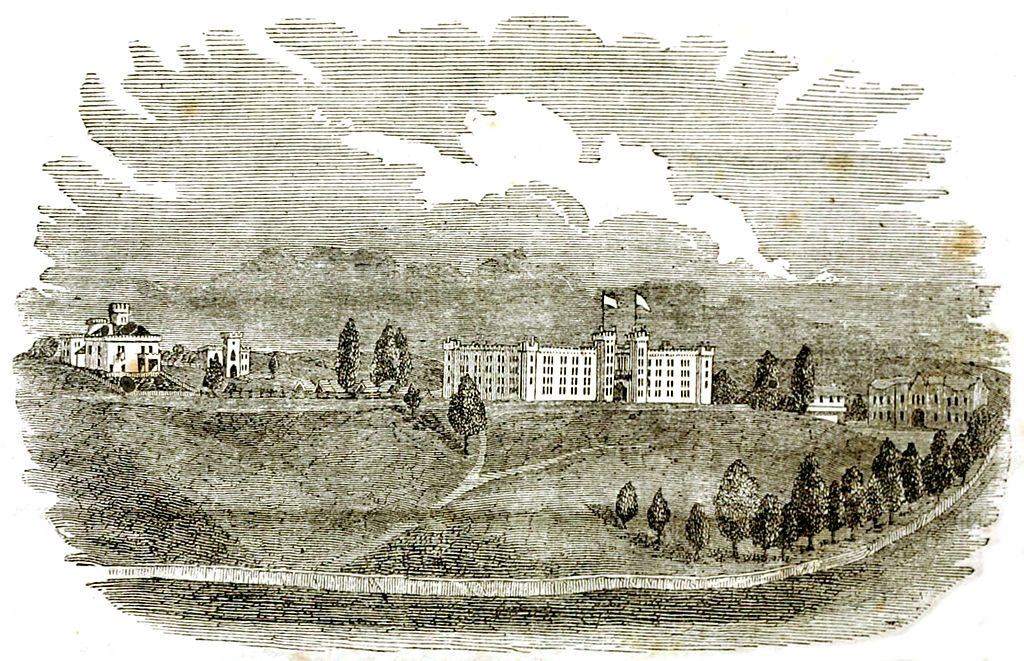

On May 10, 1864—the first anniversary of Stonewall Jackson’s death—Virginia Military Institute cadets participated in graveside remembrance ceremonies, returned to their barracks, and finished the day with evening dress parade. That night, a messenger arrived at the Institute in Lexington, Virginia.

Confederate General John C. Breckinridge needed the cadets and had decided to accept the faculties’ previous offer from a few weeks earlier in the spring. Superintendent Smith took the message and immediately issued orders. Cadet John Wise (son of a former Virginia Governor) later remembered the moment when the boys awoke to the sound of the long roll of the drum and hastily formed to hear the orders.

There in the darkness, with flickering lights creating shadows on the barrack walls, the cadets heard the news they had been waiting for. General Breckinridge needed “your assistance at once,” and the march north would begin in the morning, taking rations and a section of artillery. The boys silently waited at parade rest, “but oh! The beating hearts. Oh! The kindling eyes. Oh! The wild rush of pride, hope, and joy that overwhelmed us as we felt that our hour had come at last!” When the cadets were dismissed, a hearty cheer echoed, and the students rushed to prepare for the coming march.

Dawn came on May 11. Lieutenant Colonel Scott Shipp, commandant of cadets, assembled the infantry battalion and started them on their journey north to Staunton, a distance of approximately 36 miles. The boys mostly behaved with proper military decorum, but they could not resist stomping on a creek bridge to make it rock and sway dangerously. The cadet artillery detachment left Lexington later in the day, delayed by the necessity of finding suitable horses to pull their cannon and caissons.

As the sun rose higher and the dust increased, marching along the grades of the Valley Turnpike lost its glamor, and the cadets’ enthusiasm started to fade. The road’s hard-packed surface was rough on the body, creating aching legs and blistered feet. By the evening of May 11, the boys had marched eighteen miles and camped off the pike near Midway. It rained that evening, and some cadets snuck off to a nearby Presbyterian church, propped open a window, crawled inside, and curled up on the seat cushions.

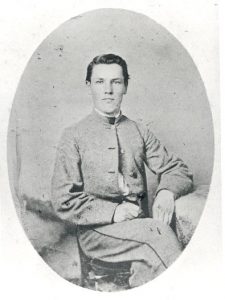

The following day, marching conditions had changed significantly due to the wet weather. “[T]he roads were awful perfect loblolly all the way and we had to wade through like hogs,” lamented Cadet “Jack” Stanard, who had previously been so anxious to leave school and become a soldier. Even with the road difficulties, the battalion covered another eighteen miles. Lieutenant Colonel Shipp rode ahead to Staunton, reporting to Breckinridge and receiving instructions to encamp the cadets “one mile south of Staunton.” May 12th—two days after the orders arrived—the cadets had joined Breckinridge’s assembling army.

At some point during their brief stay near Staunton, the battalion marched passed a girls’ school, and the Institute musician’s fife shrilled “The Girl I Left Behind Me.” One cadet admitted, “Of all places on earth Staunton seemed to have the most girls, and we were too busy scanning their fair forms and faces to think much of the girls we left behind us.”[v] Young, full of life, and caught in the exciting ideal of going to war, the boys enjoyed their welcome to Staunton from the girls and families in the area.

While some flirted through the evening, others took time to handle more serious matters. Cadets originally from Staunton snuck home to visit their loved ones; Jack Stanard accompanied his fellow cadet Cary Taylor home, and Stanard took the opportunity to write a letter to his mother, explaining, “The Yankees are reported coming up the Valley with a force of 9,000 strong. Our Corps will run Gen. B up to 5,000 may be more. . . . Well darling Mother I have written enough I suppose to relieve your mind as to our destination so I must stop. . . .”

Later, the Confederate veterans and soldiers gathered at Staunton frowned at the cadets. Some were angry that the boys stole the girls’ attention while others merely found the cadets’ appearance on the march a source of entertainment. Contemptuous mutters and a “taunting chorus ‘Rock-a-bye-baby’” angered the teens, but they kept their composure and ranks. A day of reckoning might come when those veterans would be forced to acknowledge the training and determination of the cadets on a battlefield.

Orders came to march farther down the Valley Pike on May 13, and each mile brought Breckinridge’s army and the boys from the Virginia Military Institute closer to Franz Sigel’s Union troops and the possibility of battle. When they left Staunton, nearly 40 miles of Valley Pike still lay between them and the crossroads town of New Market — the distance would be covered in two days.

In total the VMI Corps of Cadets covered nearly 80 miles in four consecutive days, averaging of 18-20 miles of marching per day. The road conditions were less than ideal for part of the way, but the young men — though unaccustomed to veteran campaigning — kept the pace and held their ranks. Though summoned to act as reserves for Breckinridge’s scrambled-together force, the Corps of Cadets took a decisive role in the Battle of New Market on May 15, 1864 — filling a gap in the Confederate lines and later participating in a charge that captured artillery and pushed the Union army into retreat.

The Cadets’ march to New Market is often overshadowed by the more dramatic moments on the actual battlefield, but their quick movements down the Valley Pike ensured their presence with Breckinridge’s army and their readiness to enter combat when the decision moment came to “put in the boys.”

You perfectly capture the idealism and fervor of the Corps of Cadets. They were marching to defend Virginia. Only the modern, linear and self righteous could believe they were just heading down the Valley on a slave hunt, or thinking about master/ servant paradigms. They may have been naive about what the fullness of their Cause entailed, but when Breckinridge’s call came, they knew what they were fighting for.

Thank you for an enjoyable article.

Excellent article. Thanks for writing.

Very enjoyable article, Sarah. I was wondering if we knew how may cadets actually went to New Market? You mention “the infantry battalion “ and “cadet artillery detachment”, but how many boys did that entail.

Enjoyed the “story” of Jack. So true that everyone has a story.