The Louisiana Unification Movement and the Political Limits of Reconstruction

In the messy annals of Reconstruction, one of the most perplexing episodes was the short-lived but fascinating Unification Movement of Louisiana. A New Orleans political alliance of both black and white elites, the movement tried to merge concerns over corruption and high taxes with a racially progressive agenda. The movement was biracial and elite in leadership and composition, and both reasons were the root of its demise.

Reconstruction was particularly violent in Louisiana. Those who opposed Reconstruction were vehement and bitter. Even learned men such as Charles Etienne Gayarré could declare “the Southern States were delivered to the merciless legislation of ignorant negroes, acting blindly under the guidance of white leaders.”[1] Theodore von la Hache, one of the first New Orleans musicians to gain recognition, composed “The White Man’s Banner” in 1868 for Horatio Seymour’s failed presidential bid. In 1866 one of the worst riots of the era took place in New Orleans. Meanwhile, the Republican Party of Louisiana became noted for its corruption. In this poisoned cauldron, men sought a way out.

The movement’s origins were in the 1872 Reform Party, a biracial coalition made up of people upset with political violence and bullying, as well as corruption. Although mostly made up of Democrats, it attracted a fair share of Republicans. In the end, the coalition predominantly backed Democrats in 1872 and mostly dropped its progressive racial efforts.

The movement also represented a broad disgust with both parties. It was averred that Democrats and Republicans had stirred up racial hatred for their benefit, and the movement wished to keep out party stalwarts, pointing much of its ire toward the Democrats. In March 1873, rumors of the Unification Movement were hinted at in the New Orleans Times, a conservative and pro-business newspaper. The paper asserted that racist mobs were hurting the city’s economy and that if New Orleans was intent on hurting commerce for racist reasons, they were “making asses of ourselves” before the nation.[2] Yet, Democratic newspapers, such as L’Abeille de la Nouvelle Orleans, New Orleans Herald, and even the highly partisan New Orleans Daily Picayune supported the movement, although only the Herald was enthused.

Beyond being a rejection of the Democrats, the movement was also aimed at Republicans dissatisfied with the party’s corruption, exemplified by Governor Henry Clay Warmoth. As a New Orleans Times editorial said, “You want civil equality; you shall have it, if you forsake the Northern adventurer who has plundered poor Louisiana until she is penniless.”[3] As such, the Republicans, who saw the movement as merely a means to peel off voters, were adamant in their opposition.

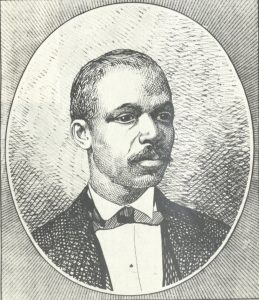

Dr. Louis Charles Roudanez typified the movement’s Afro-Creole Republican supporters. He founded America’s first black daily newspaper, the New Orleans Tribune. Roudanez opposed Warmoth’s nomination to the governorship, going so far as to run as a separate candidate. Once in power, Warmoth removed nearly all of Roudanez’s allies. Roudanez, for his part, was strident in his rhetoric and failed to gain allies. When James Longstreet, one of the Confederacy’s top generals, came out in support of the Republican Party, the New Orleans Tribune warned, “Look out new, enfranchised citizens … Jeff Davis himself will soon claim to be your best friend” and “A Rebel seeking the relief of his comrades is just another friend of the oligarchy, trying to save the oligarchy from its doom.”[4] By 1873, a desperate Roudanez was more open to making alliances with former Confederates.

The Unification Movement chose Isaac N. Marks as its chairman. He was a prominent Jewish businessman and head of the fire department’s board of commissars. He was considered a true believer in black equality, and not merely another politician looking for a vote. Marks declared in the New Orleans Times, “It is my determination to continue to battle against these abstract, absurd and stupid prejudices.…They must disappear; they will disappear.”[5]

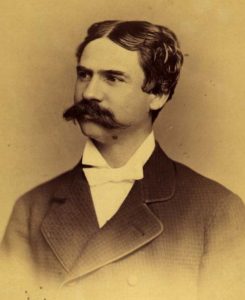

Pierre Gustav Toutant Beauregard headed the committee on resolutions. Supposedly, he was inspired after William Rosecrans told him that Louisiana must save itself in the wake of increasing racial and political violence. Beauregard’s blessing was crucial. He was Louisiana’s most famous soldier and until then had mostly stayed out of Reconstruction politics except for lending support to the Reform Party and a few public declarations in favor of black suffrage and the fourteenth amendment. Beauregard’s involvement was crucial. The New Orleans Republican called the movement “The Beauregard party” and noted that “The Creole element follow him as the people of France followed the Little Corporal [Napoleon] during the early days of this century.”[6] The paper declared that the movement was the most liberal proposed in America.

Another key member was Judge William M. Randolph, scion of a great Virginia family and an acclaimed orator. Neither Randolph nor Beauregard were seen as scalawags, for despite their more progressive views on race, neither of them were Republicans. Beauregard in particular despised the party of Lincoln, and his letters were filled with bitter sentiments.

There were several important black members. One was Lieutenant Governor Caesar Antoine. Although powerful, he was also was associated with the corrupt “Customs House” wing of the Republican Party, so he was not wholly trusted. Roudanez joined along with philanthropist Aristide Mary. Both were out of favor with the Republican Party and looking for a chance to re-enter the political field. Another important player was state Senator James H. Ingraham. He served as a captain in the 1st Louisiana Native Guards. He qualified his endorsement by declaring, “We have no disposition to Africanize this State.”[7]

The biracial committee, headed by Beauregard, released “An Appeal for the Unification of the People of Louisiana.”[8] It included support for full political and civil equality. The appeal went as far to state, “That in view of numerical equality between the white and colored elements of our population, we shall advocate an equal distribution of the offices of trust and emolument in our State, demanding, as the only conditions of our suffrage, honesty, diligence and ability.”[9]

Support came in from newspapers. The Catholic Archbishop of New Orleans, Napoleon Joseph Perche, asked parishioners to give it their support. Ex-Governors Paul O. Hebert and Alexandre Mouton sent encouraging letters. Hebert, who had served as a Confederate general, was also joined by ex-Generals Randall L. Gibson, Harry T. Hays, and John Lewis. Leon Querouze, who led the Orleans Guard Battalion, and was wounded at Shiloh, also endorsed the movement. The Orleans Guard Battalion was made up of the city’s Creole elite and had included Beauregard as a private. Many of its members followed Querouze’s lead.

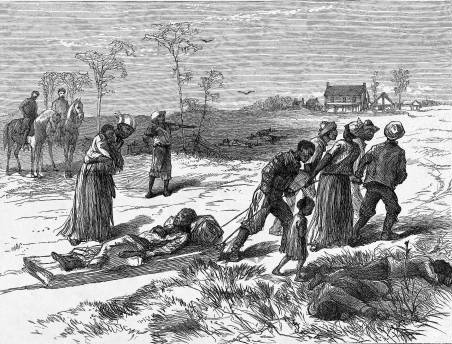

Unification was not popular in the rural parishes, where violence was common. In Grant Parish along the Red River, over one-hundred people died in the Colfax Massacre, mostly former slaves. The Shreveport Times was particularly adamant, saying “The battle between the races for supremacy … must be fought … boldly and squarely; the issue cannot be satisfactorily adjusted by a repulsive commingling of antagonistic races, and the promulgation of platforms enunciating as the political tenets of the people of Louisiana the vilest Socialist doctrines.”[10] In such a climate, Unification had no chance outside of New Orleans.

Opposition to Unification was not limited to the countryside. Frederick Nash Ogden, a Confederate cavalryman and diehard opponent of Reconstruction, called Unification a “Covenant with Hell.”[11] Beauregard came under such harsh criticism he decided to answer his accusers in a letter he sent to the New Orleans Daily Picayune. He affirmed his support for the platform, particularly voting rights, because it would mean the defeat of the “vampires who are sucking the very life blood of our people, whites and blacks.”[12] He also stated that Louisiana could only prosper with equal rights. He did not end there. Beauregard made it clear that social equality was not sought, stating “we often share these privileges in common with thieves, prostitutes, gamblers and others who have worse sins to answer for than the accident of color.”[13] Beauregard though was pilloried by some of his fellow Southerners. Reverend Abram J. Ryan, once among his friends, declared in the New Orleans Morning Star and Catholic Messenger that Beauregard was “lame” and “The end of the movement is the moral, social, and political salvation of Louisiana.”[14]

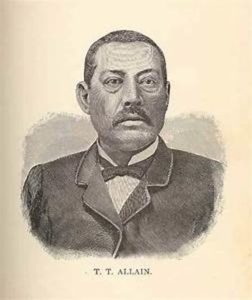

On July 15, at Exposition Hall, the Unification Movement held a make or break meeting. A large crowd gathered, mixed race but majority black. Marks gave the opening address, saying, “We came here tonight … to lay upon the altar of our country all the prejudices of the past, to recognize all citizens of the United States as equals before the law” and “to determine among ourselves that we will reunite the population of Louisiana, and that we will work together as one people for the redemption of the State.”[15] After Marks, state Senator Theophile T. Allain, born a slave and widely respected, made a plea for justice that was well received.

Yet, the next three speakers showed the movement’s leaders were rank amateurs. Allain was followed by James Davidson Hill, one of the owners of the Picayune. His speech was short and if not wholly bad it was not exciting. As a Democrat, such a plea seemed more like a ploy to split Republicans. Then came state Senator J. Henri Burch, a black member of the Customs House faction. Burch gave a terrible speech. It was long, verbose, in places pompous, and calculated to insult. Burch questioned why “Southerner[s], who, from the very fountains of their being … were filled with unreasoning prejudice and wicked hate” would make common cause.[16] Although Burch said he was impressed that they had made common cause, he mentioned tensions between the races and declared that black people were blameless. The entire speech had a negative, defensive, and even patronizing quality.

Burch was followed by James Lewis, the black administrator of improvements in the city council. He avoided the guarded language of Allain and Roudanez. He declared the black residents of Louisiana would support the defeat of Republicans but only once those rights were assured. It might have been just, but it was certainly political poison for a fragile movement.

The July 15 meeting was a disaster. The New Orleans Republican, which enjoyed mocking the movement as a fraud, noted that the meeting was missing key white figures. Randolph and Beauregard were not present. The paper reported it was a failure but tellingly added that Burch’s speech was “polished” and “a living example of that progress the African race is capable of making under Republican rule.”[17] It was a farcical, partisan statement in that Burch was a terrible speaker and a corrupt politician of the first rank. Indeed, it is likely Burch was a Republican plant, meant to make the kind of speech that would damage the nascent movement. Lewis, also a member of the Customs House faction, was openly accused of sabotaging the meeting.

Unification would take away voters from both parties and that was one reason it failed. In the streets of New Orleans, hardcore Republicans and Democrats brawled. Violent measures were used and intrigues and skullduggery of every kind were utilized, both against opposing parties and within the parties themselves. But on one thing both parties were clear. They wanted to get elected, and they both hated the Unification Movement. Of the two, Republicans were generally more hostile, but Democrats were perfectly willing to let it die.

Unification also failed in part because it did not provide an attractive economic platform. When Marks gave his address on July 15, he mentioned integrated schools. One man in the crowd then asked if the wealthy Marks intended to send his children to an integrated public school. In that one question, the movement’s weakness on class and race was exposed. For all the New Orleans Times talk about business, there was little in the appeal to indicate that equality would mean more jobs and better wages. It was equality for the sake of equality, a sentiment that was fine for Marks. It was also equality for the sake of defeating Republicans, which was fine for Beauregard. It was not equality with a stated material benefit for the skeptical Irishman or immigrant competing with recently freed slaves over jobs in New Orleans.

The desire for compromise in 1873 gave way to renewed violence in the city streets. In 1874, the city fought its own civil war with the battle of Liberty Place. One of the participants was Michael Musson, a former member of the Unification Movement who joined Ogden’s White League. Although Hays was not present at Liberty Place, he too supported the White League, as did Querouze.

Despite the violence, blacks did retain voting rights in Louisiana after 1874. Gibson, who disavowed the White League, was elected to Congress with the support of black voters. Beauregard failed to support the movement after its birth. He was too prickly, defensive, and clumsy for the brawl that was Louisiana politics. However, he stayed loyal to its ideals and aided Gibson’s election efforts.

Years later, at the height of Jim Crow laws and lynching, Rodolphe Desdunnes wrote “The movement failed but we have retained the memory of it. If it did not succeed, it was because it was premature.”[18] Desdunnes was a member of the Comité des Citoyens, which opposed Segregation. Its leadership was mostly Afro-Creoles and included Unification members such as Mary and Antoine. Their efforts ended in defeat with Plessy v. Ferguson. But the ideas did not die. As the historian Justin Nystrom wrote, the Unification Movement’s “manifesto bore a remarkable resemblance to the Civil Rights Act of 1964.”[19] In that sense, it was far ahead of its time. Although the Unification Movement failed, it showed that even in the swelling tide of scientific racism, political violence, and Gilded Age corruption, men as diverse as Roudanez, Allain, Marks, and Beauregard were unwilling to simply be swept away in the frenzy.

[1] Wetta, The Louisiana Scalawags, 6.

[2] New Orleans Times, April 29, 1873

[3] New Orleans Times, June 6, 1873

[4] Wetta, 151.

[5] New Orleans Times, July 23, 1873

[6] New Orleans Republican, July 3, 1873

[7] New Orleans Republican, June 1, 1873

[8] Daily Picayune, June 17, 1873

[9] Daily Picayune, June 17, 1873

[10] Shreveport Times, July 19, 1873

[11] Nystrom, New Orleans After the Civil War, 150.

[12] Daily Picayune, July 1, 1873

[13] Daily Picayune, July 1, 1873

[14] New Orleans Morning Star and Catholic Messenger, July 6, 1873

[15] New Orleans Times, July 16, 1873

[16] New Orleans Times, July 16, 1873

[17] New Orleans Republican, July 17, 1873

[18] Medley, We As Free Men, 86.

[19] Nystrom, 151.

Nice article Sean!

What was Harry T. Hays’ role in the 1866 riot/massacre? He was the Orleans Parish sheriff at the time and was removed later that year by Phil Sheridan under federal Reconstruction law, right?

From what I recall, and it has been years since I read Hollandsworth, he seems to have just sat back and allowed it to happen.

Interesting. And then supported the supported the Unification movement. Challenging times.

The Collector of Customs, James Casey was brother-in-law to Pres. Grant. So, the Custom house Gang had good connections. The other wing of the Republican Party in New Orleans was led by Clay Warmoth, who took corruption to whole new level. Its a shame the moderates in both parties could not get something sustainable going. Beauregard’s role was key. He made any movement possible. But, he had his own foibles. Nice article.

Tom

Added to the complication is that Warmoth was associated with John McClernand and Grant did not like him. So the factions represented the wider fight in the Republican Party between pro and anti Grant people. Grant was never one to let go of a grudge, which made it even more bitter.

Thanks for the article I came across the Unification Manifesto, while researching my genealogy. My great great grandfather’s name appears as one of the members, S. Picotte.