What if Longstreet hadn’t been wounded in the Wilderness?

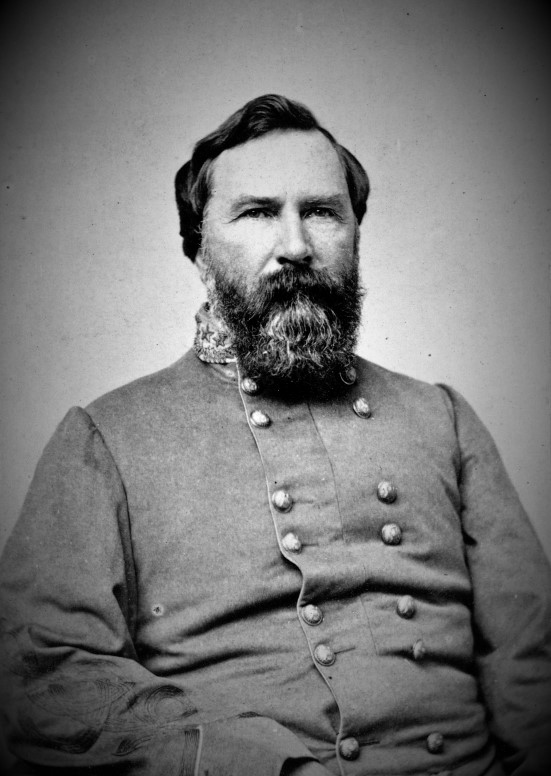

On May 7, 1864, Robert E. Lee made one of his most critical decisions of the entire Overland Campaign: who to promote to take the place of his wounded Old Warhorse, James Longstreet. Longstreet was caught in the middle of a friendly fire incident early on the afternoon of May 6 (see yesterday’s post for details if you need them).

On May 7, 1864, Robert E. Lee made one of his most critical decisions of the entire Overland Campaign: who to promote to take the place of his wounded Old Warhorse, James Longstreet. Longstreet was caught in the middle of a friendly fire incident early on the afternoon of May 6 (see yesterday’s post for details if you need them).

First appearances suggested Jubal Early would get the nod, although Lee ultimately picked Richard Anderson. Early, a Second Corps division commander, had been getting increasingly important assignments from Lee ever since marching to the sound of the guns and saving the Confederate right at Fredericksburg. Anderson, on the other hand, led a division in the Third Corps, but he had once served in the First Corps; Lee chose him because the men of the First Corps knew him and would, Lee thought, respond better to him than to Early. (Early would get his chance at higher command, anyway, leading the Third Corps through the battle of Spotsylvania Court House and, later in the month, taking over the Second Corps from Dick Ewell.)

Longstreet’s wounding was the first of a cascading series of command troubles for Lee in May 1864. A. P. Hill would have health problems. Jeb Stuart would be killed. Lee’s confidence in Ewell would collapse. His confidence in Hill would collapse shortly thereafter. By North Anna, Lee would have no one with whom he could strike a blow.

So, I can’t help but wonder: what if Longstreet hadn’t been wounded in the Wilderness?

Of course, there’s no way to actually answer the question, but asking it can help us better understand the implications of what actually did happen.

Longstreet was wounded around 12:30 in the afternoon on May 6. At the time, he was in the middle of launching a series of devastating counterattacks against the Federals. Longstreet’s loss in the middle of those attacks meant an immediate loss of momentum for the Confederate First Corps. Lee had to personally intervene to get the corps reorganized. When he sent the corps forward for its final assault against the Brock Road/Plank Road intersection at 4:00 p.m., Federals successfully repulsed the assault.

While there’s no way to tell what would have happened had Longstreet not been shot, we do know that Federal II Corps commander Winfield Scott Hancock, in charge of the defense of the intersection, had needed every minute of those intervening three and a half hours to fortify his position. His men constructed three lines of works. Two of them fell during the First Corps’ late-afternoon assault.

Longstreet was three-tenths of a mile from the intersection when he was wounded. Had he been able to keep the assaults pushing forward, he didn’t have far to go, and Federals were not fully fortified. (Had Longstreet attained the intersection and taken it, there’s no telling if he could’ve held it, of course, and I’m not going to risk teetering off the rails here by speculating.)

Beyond that interesting scenario, the implications of Longstreet’s wounding offer other tantalizing questions. Another–and oft-overlooked one–arises with Grant’s shift south. Let’s pretend, for the sake of pretending, that the battle unfolds exactly as it really did, but this time, Longstreet remains in command. In reality, Lee ordered Anderson to begin his march out of the Wilderness at 2:00 a.m. on May 8. Because of a forest fire in the area, Anderson actually began his withdrawal at 10:00 p.m. on May 7. That four-hour head start ended up making all the difference by the morning of May 8 outside Spotsylvania Court House, where Anderson rushed on to the scene just in time to bolster Stuart’s cavalry as it delayed Grant’s advance down the Brock Road. Would Longstreet have begun his march out of the Wilderness on the same timetable as Anderson?

Let’s say he does, and May 8 unfolds as it actually did, with Longstreet instead in command of the First Corps. I have a tough time reimagining Spotsylvania turning out much differently even with Longstreet on the scene. I doubt anything on the First Corps’ front would have changed much either way since Federals mostly called the tune on that sector of the battlefield. However, knowing how defensive-minded Longstreet could be, and knowing how defensive-oriented the campaign became, I tend to imagine Longstreet as a good fit for the style of warfare that played out during the two weeks at Spotsy.

The biggest impact of Longstreet’s presence at Spotsy, I think, would actually have rippled elsewhere in the command structure. When A. P. Hill fell ill with his recurring “social disease” on May 7-8, who might Lee have tapped to take temporary command? In real life, Jubal Early got the nod, but might Anderson have gotten the nod instead because he was already in the Third Corps? How might that have impacted events at, say, Heth’s Salient on May 12 or Myer’s Hill on May 14?

Most intriguing to me is the idea of James Longstreet at the North Anna River. At this point, we’re so far into the realm of speculation that it’s impossible to even imagine whether Lee creates his now-famous “inverted-V” position. What we do know, though, is that Lee had exhausted himself by the time he got to the North Anna and that he suffered from acute dysentery. On May 24, as Federals stumbled into the trap Confederates had laid, a delirious Lee, confined to his tent, mumbled “We must strike them a blow….” But with Lee thus incapacitated, he had no one to rely on to step into his boots and strike that blow. Ewell had fallen from grace (and was, anyway, suffering from dysentery of his own). Hill had just botched the fight at Jericho Mills the day before. Anderson, still new to command, anchored the center of the line and so couldn’t really maneuver, anyway.

But imagine Longstreet on the scene. Lee would have had the confidence to let his Old Warhorse step up, as second-in-command of the army, to strike the blow. Even with the First Corps holding the center of the line and thus unable to be the striking force, Longstreet surely would have ordered Ewell’s second corps forward, closing the jaws of the trap Lee had constructed.

Would the Confederates have found success or defeat in that effort? No one can say, of course (and, again, I’m not jumping off those rails!). Either way, though, I suspect North Anna would not be as overlooked today had the Army of Northern Virginia struck a blow there.

Longstreet’s absence from Lee’s army in the Overland Campaign has one other significant impact for us to consider. Lee had exactly two men in his army who knew anything about Ulysses S. Grant, imported from the west: Cadmus Wilcox and James Longstreet, both of whom had served with Grant in St. Louis. If Longstreet remained with Lee’s army, what insights might he have been able to share about his old friend. “That man will fight us every day and every hour till the end of the war,” Longstreet had warned Lee—an admonition that proved entirely true. How might Longstreet’s council on Grant have helped Lee as “every day and every hour” continued to pass?

After his wounding, Longstreet would return to Lee’s army in October. By then, though, one of Lee’s own predictions was coming true: the armies had settled into a siege, which meant the end of the war would only be a matter of time.

Interesting scenario(s). Given the situation among Lee’s subordinate officers, and his lack of confidence in them or their being hampered by their own ailments and thus their availability being possibly affected, what might Longstreet’s evaluations of them have been? After all, he would have to depend on at least some of them to carry out his orders.

That said, on the most recent “Question Of The Week” pertaining to the Battle of Chancellorsville, I asked “What if Longstreet had been there?” Chris M, do you have any thoughts about that? How might that have played out with him being available to Lee?

In the short term, based on Chris M. youtube educational, entertaining, enlightening video walkthrough of Longstreet’s wounding, I had the distinct felling Hancock gets overwhelmed by fresh Confederate troops. Grant doesn’t quit, In the longer term, Upton with his new attack tactic still happens with success. Petersburg seige still happens. Sheridan and Meade still have friction. A mine under the Confederate trenches/forts still happens, and again with drunken Union leadership. Grant still stretches Lee’s right, Five Forks may not happen but something like it does. Wilmer McLean was destined to be at the start and end of the war.

While we’re at it, how would things have changed if Hill’s troops would have been about 30-minutes quicker in getting to the Brock Road/Plank Road intersection or would have been successful in quickly pushing off Wilson’s dismounted Federal cavalry from the cross roads…??

Jame Longstreet is my great great great grandfather