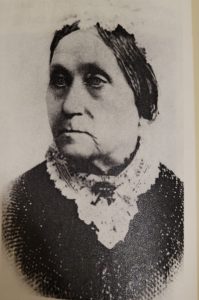

Mary Cushing: “Poor, but highly committed”

For Mother’s Day

Her boys called her “Little Ma.” She outlived them all, receiving the news that two had fallen in Federal military service. Though short in stature, she was “quiet and unassuming…. bright and witty in conversation,” a well-informed woman who read and wrote and followed her faith.[i] She endured loss and widowhood, but held her family together, raising sons known for their character. She gave to “the country in its day of need…sons so equipped in intellect, nerve, and unflinching will as to be among the most serviceable of all the soldiers and sailors of the Union army and navy.”[ii]

Raised and educated in Boston, Mary Barker Smith was 29 when she married widower Dr. Milton Cushing in Columbus, Ohio, in 1836. Described as having “splendid physical and mental constitution…and…endowed with a passionate love for life,”[iii] she moved into the frontiers of Wisconsin about a year after the wedding, taking her first baby son—Milton Jr.—on this pioneering journey. Another son, Howard, was born on August 22, 1838, and from entries in her Bible, Mary may have feared she would not survive this second childbirth.[iv] But she and the baby did live. With her little ones, Mary started making a home in a log cabin on 250 acres of Wisconsin wilderness. Eventually, members of the extended Smith and Cushing families also settled nearby, and the growing settlement was called Delaford.[v] More babies came quickly. Walter was born in 1839, but only lived a few days. On January 19, 1841, Alonzo was born. William joined the family on November 4, 1842.

Financial hardship in a difficult economy had driven the family to Wisconsin and continued to follow them. In April 1843, Milton and Mary sold the land and moved to Milwaukee and then Chicago. Before leaving the farm, though, Mary bought back a plot of the land measuring six by four feet; ten dollars purchased the gravesite of her baby son, ensuring its protection.[vi] It would not be the last time she marked a son’s grave.

Difficulties mounted, including more financial loss and lawsuits. The family lived in a boarding house, and Milton’s health started failing. Mary lost another baby in 1845, a baby girl who died shortly after birth. Shortly after this loss, she was pregnant again with her seventh and last child. Meanwhile, Milton left the family, planning to live with extended family in Mississippi and hoping that the warmer climate would cure his consumption. Mary chose to take her four little ones back east, to be closer to her family.[vii]

A story from this difficult trip is one of the earliest accounts of Mary’s boys trying to make life easier for their mother. Finding herself short on money, she apprehensively approached the owner of the inn where they had stayed the night. Four-year-old William trailed along and piped up, telling the proprietor: “You mustn’t charge my muver much money. She hasn’t very much!.”[viii] Finally, reaching family in Boston, Mary worried about her absent husband; one letter remains, written in November 1846 and carrying Milton’s thankfulness that she and the children had reached safety. Mary never saw her husband again. He died in Gallipolis, Ohio, on April 22, 1847, probably enroute to his family in Massachusetts.

With her new baby—Mary Isabel—in her arms and no money to her name, Mary remembered her husband’s former directions that if anything ever happened to him to go to Fredonia, New York, and live among his family. Disregarding her own sisters’ advice, she moved her children to Fredonia during the summer of 1847. The extended family welcomed her, even offering to adopt some of the children, but Mary determined to keep her family together. Instead, she worked as a seamstress, earning enough money to purchase a small house with a little assistance from the relatives. Here, she opened a school where she instructed her own children and many other youngsters from the neighborhood.[ix]

When not in school, the Cushing boys did odd jobs around the community, earning extra money which they proudly gave to Mary. Even so, the boys had a childhood of mischief, and their antics must have made the neighbors wonder and caused their mother a few moments of terror. Young William seemed to be the most adventurous, or at least the one who got the most stories in later reminiscences. For examples:

- William wandered off one day wearing his father’s old stovepipe hat and wasn’t seen for 36 hours. He reappeared, rescued by a sailor after walking off a pier into Lake Michigan because he had wanted to follow a steamboat.[x]

- Once graduated from their mother’s school and sent to another school, the boys formed a “military company,” drilled with their friends, and coordinated efforts to make the teacher’s life miserable and endangered…until Mary heard about the trouble and laid down the law.

- William…again…got into a quarrel with a local shopkeeper and ended up whacking the fellow on the head with an axe handle.[xi]

- Teenage Alonzo asked Miss Julia Greenleaf to attend a prayer meeting one summer evening. (They had apparently been “seeing each other” with a variety of innocent activities routinely interrupted by William.) William turned pious that night and offered to go to the religious service; Alonzo promptly declined his little brother’s company and might have breathed a sigh of relief to finally be somewhat alone with Julia. That didn’t last long. William snuck into the church, seated himself behind the couple, and joined loudly in the congregational singing, inventing new lyrics which were apparently “personal remarks” about the two people in front of him. A church leader intervened and threw William out of church, leaving a mortified older brother in the church pew.[xii]

Mary Isabel later wrote about her childhood years and the respect that her mother taught and enforced: “One trait, was very remarkable in our family. That was the respect and courtesy manifested toward each other. I never received a reproof or heard an impatient word from either of my brothers. They always displayed toward each other, and my mother and myself, the same courtesy they would [later] show to a commanding officer. The petting and love I received was enough to have spoiled me for life.”[xiii]

Mary thought of her children’s futures, especially for her sons. Milton Jr. moved to Massachusetts in 1854 where he became a pharmacist. Howard relocated to Chicago, working for a newspaper. Alonzo was sent to Fredonia Academy. Francis Smith Edwards—Mary’s brother-in-law—got elected to Congress and took William to Washington City to serve as a congressional page.

For her two youngest sons, Mary used family political influence to shape their higher education and careers. She approached Edwards and some other family members in the military, seeking appointments to the U.S. military academies. She wanted Alonzo to attend West Point, and William to enter Annapolis. On Alonzo’s recommendation, Congressman Edwards wrote: “His mother is poor, but highly committed and her son will do honor to the position.”[xiv]

Mary Cushing raised four sons and a daughter in difficult circumstances. Though a widowed mother, she held her family together and saw her sons on the paths to successful careers. When she sent her two youngest boys to the military academies, she could hardly have imagined the coming storm of war that would take them away from her. William (though kicked out of Annapolis) would become a rising star in the U.S. Navy, recognized for his daring feats during the Civil War; he would survive. Alonzo graduated from West Point in the Class of 1861. Her two other sons, Milton and Howard, also served in Union forces during the Civil War and survived the war.

Tragically, Mary outlived all her sons. Alonzo was the first to fall, killed in combat at Gettysburg on July 3, 1863, defending The Angle to the last. Then, in 1871, Howard, a cavalry lieutenant, was killed by Apache warriors in Arizona. William succumbed to tuberculosis in 1874 and is buried at Annapolis in recognition of his restored reputation and Civil War exploits. Milton also died of tuberculosis in 1887. Mary Isabel outlived her mother, and she and her husband took care of Mary in her later years in their St. Joseph (Missouri) home.[xv]

Records hint that Mary had come to depend heavily on Alonzo for financial assistance, advice, and support during his West Point years and Civil War service. However, as far as historical records reveal, Mary saw her son Alonzo only twice after she sent him to West Point. Once during his official furlough in 1859, and once in the winter of 1863. Faithfully, he sent at least $20 monthly from his cadet and military pay to support his mother and sister. During Alonzo’s winter leave, Mary had decided she wanted to move to Massachusetts to be closer to her sisters. The lieutenant wrote in a letter as he returned to the Army of the Potomac:

“I left mother enjoying herself very much in Chelsea. She is at Aunt Margaret’s. The only thing required to make her perfectly happy is to hear from you [William] and [Howard]. Aunt Margaret is going to have her fat** in a month… Mother will stay till May or June.”[xvi] (**The term “fat” in Civil War era correspondence is typically a reference to good health; see this blog post for more explanation.)

Alonzo’s death at Gettysburg carried home all the pain of losing another child and also the end of Mary’s financial security. Later in her life, Mary did receive a pension of $17 per month from the U.S. government, a small recognition her difficult circumstances and her sacrifice.[xvii]

Mary did visit Alonzo’s grave at West Point in October 1865. She wrote to William, revealing her sorrow and outrage:

“After talking with the Adjutant of the post, I went in a carriage to dear, dear Lon’s grave. Sadly neglected we found it. Not even sodden with nature’s beautiful green, for in raising a costly monument to the memory of Gen. Buford, Allie’s grave had been trampled on, and nearly levelled with the Earth! So our country rewards her fallen sons; fallen in her defense! A nameless, neglected grave! We deposited there a beautiful wreath made by cousin Martha and I set out a white rose bud brought from Fredonia.”[xviii]

She went to New York City and purchased a grave marker for $100, wrote the inscription to be engraved, and ensured that her son would at least be remembered. Mary Cushing died on March 26, 1891. One hundred twenty-three years later, Alonzo Cushing was granted the Medal of Honor, and his name and story surged back into American historical consciousness. “Little Ma” would be proud. She raised good sons and a daughter, and she knew it. She only wished others knew.

Epilogue:

Today, Alonzo Cushing’s name is repeated daily on Gettysburg battlefield as groups wander or study at The Angle. His photograph is enlarged and emblazoned on the walls of museums. The story of the artillery officer’s courage and commitment is told and retold — how he ordered the remaining cannons of his battery forward to meet the coming infantry attack, how he stayed in command though desperately wounded. The son did “honor to the position,” and his mother would see how a grateful nation now rewards the fallen son at Gettysburg.

Sources:

[i] Kent Masterson Brown, Cushing of Gettysburg: The Story of a Union Artillery Commander (Lexington, University of Kentucky Press, 1993). Page 21.

[ii] Theron Wilber Haight, Three Wisconsin Cushings, (Wisconsin History Commission, 1910). Page 28. Accessed through Project Gutenberg.

[iii] Ibid., Page 9.

[iv] Ibid, Pages 9-10.

[v] Kent Masterson Brown, Cushing of Gettysburg: The Story of a Union Artillery Commander (Lexington, University of Kentucky Press, 1993). Page 13.

[vi] Ibid., Page 14.

[vii] Ibid., Page 16.

[viii] Ibid., Page 16.

[ix] Ibid., Page 19.

[x] Ibid., Page 22.

[xi] Ibid., Page 22-23.

[xii] Ibid., Page 26.

[xiii] Jamie Malanowski, Commander Will Cushing: Daredevil Hero of the Civil War (New York, W. W. Norton & Company, 2014). Page 23.

[xiv] Kent Masterson Brown, Cushing of Gettysburg: The Story of a Union Artillery Commander (Lexington, University of Kentucky Press, 1993). Page 29.

[xv] Ibid., Page 262.

[xvi] Ibid., Page 165.

[xvii] Theron Wilber Haight, Three Wisconsin Cushings, (Wisconsin History Commission, 1910). Page 52. Accessed through Project Gutenberg.

[xviii] Kent Masterson Brown, Cushing of Gettysburg: The Story of a Union Artillery Commander (Lexington, University of Kentucky Press, 1993). Page 262.

What a fine mother to celebrate on this day. Anyone would have been proud of the accomplishments and character of her children (Will a little shaky here though the country can always celebrate madmen in war times), but to manage that feat as a solo parent in the 19th century is truly admirable. Thanks for writing about Mary Cushing.

Thanks for sharing this touching story! What a wonderful example of a mother. Her children grew up to love and respect her and she did the best she could after her husband died and she had to rear her children in extreme poverty. Beautiful tribute to a beautiful lady!

Thanks for this. I think the reference to Cushings in Wisconsin should be Delafield, not Delaford

(my family also happen to have been pioneers in that area, though several miles south of Delafield in Genesee).

Mary Cushing was the rock of the family. She appears to be an extraordinary woman who raised a fine family in very, very difficult circumstances. I’m currently reading Kent Masterson Brown’s book now and I’m astounded at number of Alonzo’s relatives who died from tuberculosis. A difficult period to grow up in for sure.