America’s First Air Force: Union Aeronauts and McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign Part One – Maker of Water

ECW welcomes guest author Jeff Ballard

West’s levitation was possible only because of his perch in the basket of the United States Army 1st Balloon Corps’ hydrogen balloon, Intrepid. The balloon’s other occupants were its “pilot,” Thaddeus Lowe, and Parker Spring, a Signal Corps telegraph operator. Satisfied his report was complete, West instructed Spring to send the communication. The Morse coded message traveled through the telegraph wire, tied to the balloon’s tether, to the headquarters of the Army of the Potomac. The commanding general, George B. McClellan, instantly received the message and, after consulting a map, he dispatched a rider with instructions to his corps commanders to, “Hold ourselves in readiness for an attack.”1

Since the beginning of time, war has inspired mankind’s most powerful and awe-inspiring creations. Many innovations, like nuclear weapons, wrought destruction and death on a grand scale. Others used microscopic organisms harvested from penicillin mold to cure disease. The American Civil War (1861-1865) was no different. A multitude of inventions can be attributed to the conflict. The first widespread use in combat of rifled firearms and artillery pieces, repeating rifles, machine guns, and landmines are all the deadly offspring of this war. Non-lethal developments of the Civil War included powerful calcium flares, airborne red, white, and blue nocturnal signal lights, and chemical smoke grenades.[1] Mobile gas generation technology supplied a virtually endless amount of hydrogen to fuel “oxyhydrogen” arc lamps. Engineers demonstrated that “one of these lamps produced enough light for hundreds of people to work by, whether inflating the balloons, or felling trees, etc.”[2]

Perhaps the most overlooked, non-lethal innovation of the Civil War was the tethered, lighter-than-air (hydrogen gas) balloon. This nineteenth-century airborne curiosity quickly found its purpose on the Civil War battlefield as an early warning sentry, cartography aid, artillery-spotting platform, signaling, and intelligence gathering vehicle. Once adapted for use in the field and integrated into the U.S. Army, the balloon demonstrated its most significant contribution to the Union war effort at the battle of Fair Oaks, the highpoint of McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign.

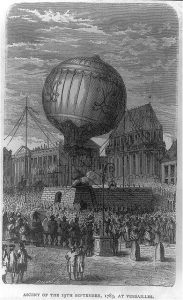

Approximately eighty years passed from the first experiments on the lifting properties of superheated air, and the hydrogen balloon’s appearance on the battlefield over Virginia. The Montgolfier brothers first pondered such a creation when, in 1783, the Frenchmen “idly watched a fire of burning leaves and became fascinated as wispy embers floated in the air.”[3] June of the same year saw the brothers fill a paper bag, thirty-three feet in diameter, with hot air from a sheep’s wool fire. The balloon, a word borrowed from the Italian Pallone, meaning “large ball,” rose to an altitude of 1000 feet, and the age of ballooning was born.[4]

Within two months the balloon Globe was demonstrated to the king of France and the American statesman, Benjamin Franklin. Globe reached an altitude of 2,000 feet and traveled fifteen miles in free flight. The envelope of the unmanned Globe was constructed of silk, coated with natural rubber, and filled with 22,000 cubic feet of “inflammable air.” [5]

Discovered by the English chemist Henry Cavendish in 1766, this lighter-than-air gas, which he named “hydrogen,” from the Greek words “hydro” and “genes” meaning “water” and “generator” or “maker of water,” was seven times lighter than atmospheric air.[6] The gas was so named because water was released when the gas was burned. The odorless, colorless, tasteless gas was created when ferrous metals were dissolved in sulfuric acid. It was also highly flammable, as a desirable quality for some applications, like streetlights, but not ideal for ballooning.

The French Revolution (1789-1793) ended the ballooning craze in France. While the phenomenon was slow to appear in the United States, the nineteenth century witnessed an even greater fascination with the balloon than the preceding one. Charles Green, an American doctor in London, brought the pastime to the United States in 1837 after he successfully crossed the English Channel in a balloon. At the mercy of the winds, however, the first cross channel attempts failed because the pilots, known as “aeronauts” or “aerialists,” were unable to vary the balloon’s altitude or change its direction.

Green was the first to address the problems of free flight navigation. He carried a 1,000-foot coil of rope that he lowered and dragged along behind the balloon.[7] The friction of the rope slowed travel in the wrong direction until winds in the correct direction could be located. Another aerialist to attack the problem of in-flight navigation was John Wise. Wise invented the “rip panel” which allowed for the venting of hydrogen to reduce the balloon’s altitude.

On July 1, 1858, John La Mountain’s balloon Atlantic combined all these innovations and ascended in St. Louis, Missouri, eventually crash-landing in Henderson, Maine days later. He set an air travel distance record for its time. After his 800-mile trek from Missouri to Maine, crossing the Atlantic Ocean seemed quite possible and became the ultimate challenge for every balloonist of the era.[8]

One such aerialist was Thaddeus Sobieski Constantine Lowe (1832-1913). The twenty-nine-year-old New Hampshire native had devoted his life to scientific experimentation and invention. He now set the transatlantic prize in his sights. An egotistical self-promoter, Lowe had already secured considerable funding from a group of Philadelphia investors for the “Great Transatlantic Quest” when the clouds of war derailed Lowe’s adventure.

Lowe could not have known that a little more than a year later he would become the Chief Aeronaut of the Union Army in command of America’s first air force.

Jeff Ballard is a historian, writer, and the Editor-in-Chief of The Saber and Scroll Journal. He has written numerous magazine and journal articles on topics in military history, American political geography, and social history. He earned his master’s degree in Military History, with Honors, from American Military University in 2015. Jeff’s thesis and the bulk of his subsequent research and writing focus on shifts in US Navy tactics and doctrine during the Guadalcanal Campaign 1942-1943. This native Californian lives in Huntington Beach with his wife Carol, son Andrew, and Chihuahua/Min-Pin mix Taco Bell.

[1] Duane J. Squires, “Aeronautics in the Civil War” The American Historical Review 42, no. 4 (Jul., 1937), 652-669. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1839448 [accessed: April 17, 2022], 661.

[2] Charles M. Evans, War of Aeronauts: A History of Ballooning in the Civil War (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2002), 166.

[3] Ibid., 20.

[4] Jennifer Tucker, “Voyages of Discovery on Oceans of Air: Scientific Observation and the Image of Science in an Age of Balloonacy” Science in the Field 2, no.11 (1996). http://www.jstor.org/stable/301930 [accessed: July 15, 2013], 150.

[5] Evans, 21.

[6] Tucker, 150.

[7] Evans, 27.

[8] Charles M. Evans, War of Aeronauts: A History of Ballooning in the Civil War (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2002), 32.

… and so it begins! Yay Jeff!! Brilliant!

Awesome article. This is one of my favorite topics!

While the French Revolution ended the craze in France, the Revolutionary Wars led to the first use of balloon observation in 1794 at the battle of Fleurs.

OOPS that is Fleurus in 1794.

Very interesting article and I look forward to reading more!!