“New Orleans gone and with it the Confederacy” – The Fall of New Orleans

ECW welcomes back guest author Patrick Kelly-Fischer

The signposts of my mental outline of the Civil War have always been major land battles – Shiloh, Antietam, Gettysburg, Vicksburg. The histories we grew up on are framed around these titanic battles. They’re the most popular battlefields to visit, and it would be intuitive that the most important turning points of a war are its biggest battles.

But few (if any) of these were truly decisive. Some of the largest were fought to a virtual draw. Conversely, some of the most profound, strategic consequences and missed opportunities were the result of battles that have historically flown a little more under the radar: Glorieta Pass and Monocacy, for example, saw relatively few troops engaged by the standards of the Civil War and don’t make their way into many history textbooks, but they were disproportionately consequential. To that list I would add the capture of New Orleans.

At the outset of the war, New Orleans was the 6th largest city in the country, and by far the largest in the Confederacy. At a population of 168,675, it was larger than Charleston (40,522), Richmond (37,910), Mobile (29,258), Memphis (22,623) and Savannah (22,292) combined. New Orleans alone was larger than the state of Florida (140,424).1

But by late April of 1862, Confederate Maj. Gen. Mansfield Lovell, a former New Yorker, had only a scratch force left to defend the city. The garrison had been stripped nearly bare as the Confederacy first sent thousands of troops to reinforce General Leonidas Polk in Columbus, KY, and then to reinforce Generals P.G.T. Beauregard and A.S. Johnston ahead of the battle of Shiloh.2

In his report after the battle Lovell wrote, “I will here state that every Confederate soldier in New Orleans, with the exception of one company, had been ordered to Corinth, to General Beauregard in March, and the city was only garrisoned by about 3,000 ninety-day troops, called out by the governor at my request, of whom about 1,200 had muskets and the remainder shot-guns of an indifferent description.”3

The primary obstacle to a naval attack from the Gulf was a pair of forts. Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip, 75 miles downriver from the city, were garrisoned by a mere 1,100 troops. As early as 1861, Beauregard had predicted that “any steamer could pass them in broad daylight.” Having been an engineer in charge of the city’s defenses before the war, Beauregard was well qualified to speak to its vulnerabilities. He recommended an obstruction be placed in the river to prevent Union warships from sailing through to New Orleans, but Confederate authorities implemented that advice slowly. By the time of the battle of New Orleans in April 1862, there was a makeshift barrier of small boats chained across the river between the forts, which had been damaged as the river ran high in the spring.4

Lovell was opposed by Flag Officer David G. Farragut, a Virginian who remained loyal to the Union – creating a scenario in which a Northern-born general led the Confederate defense of New Orleans against a Southern-born Union flag officer. Never let anyone tell you that the Civil War was a clear-cut affair.

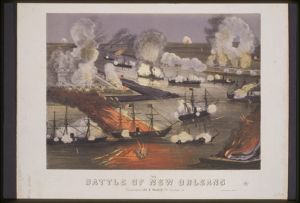

While the Union effort started with an attempt to reduce Forts Jackson and St. Philip with a flotilla of mortar boats, after several days they hadn’t succeeded in battering the forts into submission. After sending two ships to open a hole in the barrier across the river, on the night of April 24, Farragut ran most of his fleet between the forts under cover of darkness.

Captain William Roberston, a Confederate artillery officer in Fort Jackson, wrote of the battle, “I do not believe there ever was a grander spectacle witnessed before in the world than that displayed during the great artillery duel which then followed. The mortar-shells shot upward from the mortar-boats, rushed to the apexes of their flight, flashing the lights of their fuses as they revolved, paused an instant, and then descended upon our works like hundreds of meteors, or burst in midair, hurling their jagged fragments in every direction. The guns on both sides kept up a continual roar for nearly an hour, without a moment’s intermission.”5

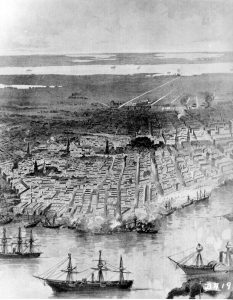

Having successfully run the forts, Farragut sailed north, briefly engaging shore batteries of field guns that lacked the position, ammunition or caliber to stop the bulk of his fleet. He also received the surrender of several hundred Confederate infantry who found themselves outgunned and, tellingly for the city’s defense, occupying the low ground compared to the Union warships. After his surrender, Confederate Colonel Szymanski lamented, “After losing some thirty men killed and wounded, with no possibility of escape or rescue – perfectly at the mercy of the enemy, he being able to cut the levees and drown me out – I thought it my duty to surrender. A single shell could have cut the light embankment.”6

Ultimately, Lovell had too few troops, too little artillery, insufficient fortifications and the disadvantage of being below the warships on the river. As it was, Lovell’s army had already been stripped bare in an effort to reinforce Albert Sidney Johnston in the effort to turn the tide after the losses of Fort Henry, Fort Donelson and Nashville – and throughout his time in command, there was constant tension and lack of cooperation between the Confederate army and navy forces tasked with defending the city. On March 6, he wrote to Confederate Secretary of War Judah Benjamin that, “This department is being completely drained of everything…We have filled requisitions for arms, men, and munitions until New Orleans is about defenseless. In return we get nothing.”7

Rather than fight it out in the city with, in his words, a few thousand “miscellaneous and half-armed militia of the city”,8 Lovell abandoned New Orleans and retreated toward Baton Rouge. Major General Benjamin Butler’s 15,000 Federal troops occupied the city without a fight, though his occupation would be infamous.

While it wouldn’t have felt this way to the men doing the fighting and dying, casualties were incredibly low by the standards of the day – 200 or so on each side, though Confederate naval losses are hard to pin down, as well as the various small Confederate garrisons that eventually surrendered.9

But what did the loss of New Orleans really cost the Confederacy?

Owing in large part to its location near the mouth of the Mississippi River, the city was the heart of commerce and trade in the South, and the fourth-largest commercial port in the world. Amanda Foreman described it as “the epicenter of the slave trade and the gateway not only for the majority of the South’s cotton crop, but also for its tobacco and sugar.”10

Access to outside trade was so important in part because, throughout the war, the Confederacy was badly outmatched in terms of manufacturing capacity. Without the arms industry needed to equip armies of tens of thousands of soldiers, they were forced to rely on European imports smuggled through a tightening blockade and arms captured from the enemy. But that problem was only exacerbated by losing New Orleans as an industrial base: In the 1860 census, New Orleans ranked second in value of manufactured goods among cities that seceded, behind only Richmond.11

After the war, Lt. Col. J.W. Mallet of the Confederate Ordnance Bureau wrote, “There were but two first class foundries and machine shops—the Tredegar Works at Richmond and the Leeds Foundry at New Orleans; the loss of the latter was one of the sorest consequences of the fall of that city.”12

As a center of ocean commerce and manufacturing, New Orleans could have become a hub of Confederate naval shipbuilding, something they sorely lacked throughout the war. What naval defenses the city actually mounted against Farragut’s fleet were largely converted commercial vessels, such as the small ironclad ram Manassas. But when the city fell, both the Louisiana and Mississippi were massive and powerful ironclad warships that were supposedly near completion. Instead, when Farragut ran the forts, the Louisiana served as functionally a floating battery before being blown up to avoid capture, and the Mississippi was torched without ever firing a shot.

Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory believed, very optimistically, that both could have posed a significant threat to Farragut’s wooden fleet, and eventually to the Union blockade. In particular, he was convinced that the Mississippi alone would have raised the entire blockade across the South in a matter of days. That was certainly wishful thinking – one or two ships, however advanced, would always have had limitations. But they may well have reopened New Orleans to badly-needed foreign trade, at least temporarily, and delayed future Union efforts to capture the city, allowing more time to spin up badly needed naval shipbuilding.13

The possibilities don’t end there. New Orleans was a staging point for Banks’ 1863 campaign against Port Hudson, and a source of supply for Grant’s Vicksburg campaign. But neither of those cities would have been as critically important if the Confederacy still held New Orleans. As it was, Vicksburg was an immense challenge that took Grant a year to crack – how much longer would it have taken him to restore Union control of the “Father of Waters”, as Lincoln called the Mississippi River, if he then had to campaign down the river through Port Hudson, Baton Rouge, and finally New Orleans?

Like any counterfactual, it’s impossible to answer the question of what would have happened if New Orleans was held – on its own, no one city in the South would have offset the North’s considerable advantages in manpower, arms or financing. But the scale of the defeat – and the accompanying lost opportunities for the Confederacy – help us understand why these reactions weren’t hyperbolic:

Mary Chestnut wrote in her diary, “New Orleans gone and with it the Confederacy.”14

The Richmond Examiner wrote, “The extent of the loss is not to be disguised. It annihilated us in Louisiana … led to our virtual abandonment of the great and fruitful Valley of the Mississippi, and cost the Confederacy… the commercial capital of the South..and…the largest exporting city in the world.”15

Gustavus Fox, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, called capturing New Orleans the “great event second only to the final surrender of Lee.”16

Tell us in the comments: Was this a turning point of the Civil War, and what other engagements and events were so disproportionately consequential as compared to the scale of the fighting involved?

Patrick Kelly-Fischer lives in Colorado with his wife, dog and cat, where he works for a nonprofit. A lifelong student of the Civil War, when he isn’t reading or working, you can find him hiking or rooting for the Steelers.

- Statistics of the United States Census (Including Mortality, Property, &c.) in 1860, Washington Government Printing Office, 1866, XVII-XX.

- United States. War Records Office, et al.. The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union And Confederate Armies, Series I, Volume VI, Chapter XVI. 1880, 561, 823.

- Ibid, 513.

- Dufour, Charles. The Night the War Was Lost. Bison, 1994, 29.

- Captain William Robertson, “The Water-Battery at Fort Jackson,” Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. 2, accessed via Tufts University Perseus Digital Library.

- Dufour, 282-283

- United States. War Records Office, et al.. The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union And Confederate Armies, Series I, Volume VI, Chapter XVI. 1880, 515, 841.

- Ibid, 511.

- Dufour, 283-284.

- Foreman, Amanda. A World on Fire. Random House, 2010, 110.

- Statistics of the United States Census (Including Mortality, Property, &c.) in 1860, Washington Government Printing Office, 1866, XVII-XX.

- Lt. Col. J.W. Mallet, “Work of the Ordnance Bureau of the War Department of the Confederate States, 1861-5,” Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. 37, accessed via Tufts University Perseus Digital Library.

- Dufour, 336

- Chestnut, Mary Boykin Miller, A Diary From Dixie, Appleton and Company, 1905, accessed via University of North Carolina, 158-159.

- Miller, Donald L. Vicksburg. Simon & Schuster, 2019, 118.

- Dufour, 136

This Browns fan acknowledges that the Steeler fan wrote a very informative piece. It is difficult to envision New Orleans as a major manufacturing base as it apparently was in 1862. This article lays out the consequences in a very clear and precise fashion. What seems to get more attention is Butler’s misdeeds when the strategic consequences and ripple effects of the port’s fall were huge and deserve highlighting.

Thank you! I appreciate that, even coming from a Browns fan…

Absolutely a turning point. I cannot think of any other situation during the Civil War where so much was gained for so little investment. Great article.

General Grant wrote after the war, words to the effect: “When I read the Rebel after-action reports, and the Rebel newspapers of Georgia, North Carolina and South Carolina before war’s end, stressing the vast and convincing nature of their accomplishments, I wonder that we experienced the same war; or that the South somehow managed to be defeated.”

“New Orleans a Turning Point” and recent efforts to generate substance from phantoms, without the crucial occupation of the Heights of Vicksburg, a conveniently neglected facet of the New Orleans campaign of April/ May 1862, epitomizes this attempt at myth-making. The submarine construction initiated in Louisiana was simply removed to Mobile; ironclad construction resumed in the hinterland; blockade runners redirected themselves to the swamps of North Carolina; and the Confederacy continued the fight, with every hope of winning, for three more excruciating and bloody years.

[Supporting evidence and references to be found in the Comments attached to “ECW Question of the Week for 4/25- 5/1/22” and “Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant” vol.2 pp.529- 530.]

The fact that the Rebels refused to send cotton to Great Britain removed the importance of No off the table.

Its hard to quantify an event that did not happen, but, sure, the loss of New Orleans was huge. Simply based on its large labor pool, they lost access to thousands of potential recruits, which were vitally needed as the war dragged on. As far as the port of New Orleans, by one estimate, the port exported about 275,000 bales of cotton in 1860, 213,000 barrels of grain, and about 193,000 barrels of food stuffs to US and overseas ports. Yes, that port was a huge economic engine at the time. New Orleans was the No. 1 or No. 2 exporting port in the world at the time.

Tom

As I have mentioned before, the Rebels put the embargo on their own cotton, so no one can claim, that since NO was lost, that prevented the rebels from exporting cotton. The Rebels already had taken cotton off the table.

As far as the grain and foodstuffs, how much of that was from Northern states to be shipped overseas?

Midwestern farmers sent their grain and corn to Chicago, where it was transported to Buffalo, then to Albany then to NYC for export.

That is a fair point. After the fall of Vicksburg and the Mississippi was re-opened to commerce, the economy of N.O, improved a great deal. Not sure that makes the fall of N.O. other than a major turning point in the war. But, that is a valid point. IMO.

Tom

A good book on all of this is…Southern Strategies, by Christian Keller. This book has contributions from several scholars and gives a great summary of reasons why the Confederacy failed. One of the best books I have read about the Civil War, right up there with Taken at the Flood by Joesph Harsh

New Orleans falling was a big deal in that it eliminated the Confederates’ ability to create and maintain a riverine fleet to defend their part of the Mississippi river and its tributaries. New Orleans had the second largest ironworks in the South after Tredegar, in the Leeds Company, and may have had the best boat building and maintenance facilities in the South, only after Norfolk if it didn’t surpass Norfolk.

If New Orleans was not taken as early in 1862 as it was the Confederates may have had at least 2 ironclads to stop Farragut’s advance pass the forts or somewhere before New Orleans. One workable ironclad alone sent north, would have hampered any riverine support south down the river from Memphis after Memphis fell.

Conscription also would have been fully implemented in New Orleans throughout 1862 and many more New Orleanians would have been sent off to fight. Then again, many would have been exempted since they worked in manufacturing or boat building, etc.

When I think of a turning point, I think of something which caused a continued decline in the fortunes of one opponent.

The war continued for 3 more years after the fall of New Orleans.

I consider a more significant turning point to be the AoP not crossing the Rappahannock after the Wilderness, but continuing to get on the flank of the ANV.

Ed Bearrs also thought that continuing to Spotsylvania CourtHouse was the turning point of the War.

Without a doubt taking New Orleans definitely caused a continued decline in the fortunes in the Confederacy. The war possibly could have ended in favor of the Confederacy without taking New Orleans, and Vicksburg may not have fallen by July 4, 1863. That would mean Grant likely never makes it East to do an Overland campaign. It’s complicated.

The fall of New Orleans seems to be undervalued. Whether is was the deciding factor in victory for the Union is debatable, but it was extremely significant in the Union’s victory. It probably should be appreciated more today than it is.

I agree: there is no doubt that New Orleans was significant. The newspaper-reading public, North and South thought so; Gideon Welles thought so; and Rear-Admiral- to- be David Farragut thought so. But it is my opinion that New Orleans in 1862 suffered from the same failing, of unrealized potential, as occurred at Shiloh (when the South did not press home Victory on 6 April) and Bull Run of 1861 (when the South did not pursue the fleeing, panicked Northerners east; and perhaps capture Washington D. C. in the process.) As part of the New Orleans Campaign, in written and unwritten orders, it was acknowledged that “opening the Mississippi River to unfettered use by the Union” was the ultimate goal of that 1862 campaign. The occupation of Vicksburg was included in those same orders as essential. And, had Farragut and Porter and Butler taken possession of Vicksburg early in May 1862, the New Orleans Campaign, today, might be recognized as “the Turning Point of the War.” Unfortunately for those concerned, that last Rebel thrust at Shiloh was not attempted; that pursuit east after Bull Run went begging; and Farragut’s flotilla was bluffed into not forcing the small Rebel battalion at Vicksburg, manning 30 or fewer pieces of artillery… while those artillery pieces were mostly without ammunition [as admitted in the after-action report of Brigadier General Martin Luther Smith.]

Yes, I agree as well. I do think Butler didn’t have enough troops or he didn’t send enough troops to Vicksburg after capturing New Orleans. Thomas Williams’, 1,000 – 2,000 men, might could have occupied Vicksburg, but Lovell moved quickly after leaving New Orleans and was sending men to Vicksburg and I think they could have retaken Vicksburg if Williams was somehow able to get into the city, but Williams and Farragut/Porter didn’t try, so we’ll never know for sure.

Butler might could have sent the bulk of his 10,000 men in a bum rush up the Mississippi to Vicksburg, but hard not to detail enough men to get a handle on New Orleans and its environs immediately after taking it.

BGen Martin L. Smith arrived at Vicksburg on or about 12 May 1862. In his after-action report he admits that, “the ensuing ten days were the most critical for the defense of Vicksburg… little [of our] ammunition had then arrived… Had a prompt and vigorous attack been made by the enemy…” [See OR Series 1 Vol.15 page 8.]

The questions arising are these:

– Could Farragut’s force have arrived at Vicksburg before 22 May 1862? How many days before, best case scenario?

– Could an attack by Federal forces have been launched with reasonable likelihood of success in overwhelming 1000 rebels with virtually no ammunition available to them before 22 May 1862?

– Were 13-inch mortars available to Farragut that could have been employed at Vicksburg?

Farragut tried and failed. He had insufficient troops and did bombard the city, but Vicksburg remained defiant.

In order to understand “why the New Orleans Campaign failed,” one must get down in the weeds… Here is one facet of that saga that resulted in failure:

In “The Rebel Shore: the Story of Union Sea Power in the Civil War” (1957) by James M. Merrill comes this nugget: “From extreme unpreparedness in April 1861, the Navy, after twelve months of struggling, was welded into a potent offensive weapon.” This encapsulates the improvements brought about, at direction of Secretary of the Navy Welles, and his Assistant Secretary Fox. Acquisition of ships, expansion of effectiveness of the blockade, and innovative recruiting of new sailors were some of the achievements. Unfortunately, Welles’s intended improvements included “asserting Navy equality with the Army.” Welles and Fox felt “put upon” by Seward’s “special expedition” sent to reinforce Pensacola in April 1861; and the supposed “taking of ALL the credit” by Major General Butler for the success of the joint Army/ Navy Hatteras expedition, smarted. In order to redress these abuses, SecNav Welles pushed for “equivalency of ranks, Navy to Army,” and modernization of the Navy Rank and Promotion System.

How did this impact the New Orleans Campaign? Welles and Fox went out of their way to assert Navy control of the operation: Farragut was recognized as the commander; Butler was merely accorded a “support role” (as Farragut reported, “The Army will HOLD what I TAKE.”) There was no issue of standardized orders for the New Orleans Campaign: Farragut received his orders from Secretary of the Navy Welles; Butler received his from General in Chief of the Army McClellan. And Butler received his assignment as Commander of the Gulf from President Lincoln (with the command assignment subsequently reiterated by MGen McClellan.)

As to rank… Captain Farragut was promoted to Flag-Officer in January 1862. But “Flag-Officer” was only equivalent to Brigadier General. So Farragut was given command of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron and received a Command Flag (a “Flag-Officer with a Flag” was equivalent to a Major General.) Benjamin Butler had been promoted to Major General of Volunteers in May 1861, so by rights Butler should have been the senior officer involved with the New Orleans Campaign. But, there appears to have been some other manipulation that resulted in Flag-Officer (with a Flag) Farragut being accorded title of Officer in Charge. [Note: General Orders No.37 allowing the President to install his choice from among like-ranks as commander of an expedition did not become law until April 1862, after Farragut and Butler had departed for the Gulf of Mexico.]

Also, as to rank… Secretary of the Navy Welles was intent on getting “Rear Admiral” authorized by the U.S. Congress as the senior Navy rank. Called by newspapers “the Admiral Bill,” it was finally signed into law (as Navy Grade and Pay Regulation Act of 1862) in July 1862. And Farragut, along with Goldsborough and Du Pont, received promotion to Rear Admiral on the same date in July 1862.

From my research, there is no indication that Farragut and Butler compared their divergent orders: as Senior Officer, Farragut may have assumed HIS orders were superior to Butler’s. And when McClellan was deposed as General- in- Chief in March 1862, the replacement (President Lincoln and SecWar Stanton, acting as Team General- in- Chief) appear never to have reconciled or harmonized Butler’s and Farragut’s orders.

Confusion begets confusion.

It is another great “What If” of the Civil War. I’m convinced the Farragut/Porter/Williams could haven taken Vicksburg (you provide facts that suggest as much, I think), but I’m less convinced they could hold it if they did take it. This early move to get to Vicksburg just wasn’t well planned out or organized, it was kind of done on the fly. There would have been a strong Confederate response from Richmond.

That said, if the Confederates can’t retake Vicksburg from Farragut/Porter/Williams, that changes the war dramatically. Earlier Union victory?

Lyle Smith

Thank you for taking the time to read the recent posts IRT the New Orleans Campaign of 1862. My interest was sparked a few years ago while studying the “adventures” of three of my ancestors captured at Shiloh, who were confined during May/ June 1862 in Montgomery at the Cotton Shed Prison. Numerous letters from prisoners home and diaries mentioned “the panic of Southerners in Montgomery, resulting from U.S. Navy bombardment of Fort Gaines, on or about 7/8 May and the growing fear that those Navy ships might ascend the Alabama River and attack Montgomery. Consideration was given to putting the POWs to work sinking obstructions in the Alabama River.”

First, I had never heard previously of any Union attack on the Mobile Bay forts taking place before 1864. And, second, it turned out that Commander Porter, who conducted that attack, did so without orders, while supporting Farragut’s New Orleans Campaign.

It appears that “History had been overly simplified,” leaving out this inconvenient operation; and mostly ignoring Farragut’s half-hearted May 1862 push to Vicksburg. Yet, in spite of “failing to open the Mississippi River” (which was revealed as the expected outcome of Farragut’s operation) David Farragut was promoted to Rear-Admiral. And with my curiosity aroused, I set out to find out “Why?” And then: “HOW did bad history get accepted as Truth?”

There is much more to this failed 1862 campaign than meets the eye…

We have gone form the loss of NO being a “turning point” to the loss of NO was significant.

The loss would have been more significant if the Rebels had not self-embargoes cotton. Basically they tried to blackmail Great Britain.