A Newly Uncovered Letter in the Most Ungentlemanly Porter-Miller Exchange

Anyone who has read their fair share of Civil War correspondence knows it is often very cordial, even when notes are exchanged between officers on opposing sides. However, occasionally it devolves into arguments akin to modern-day social media rants, especially when officers are discussing who is at fault in a decision.

One such example is the Porter-Miller exchange of letters. They are not widely reported. You will not find them in the Official Records, but the exchange was documented in newspapers in the weeks after they were written. Several secondary books note the exchange, including my own Defending the Arteries of Rebellion. Just recently while diving into archives in the never-ending research cycle, I found a new letter which escalates the tension even further.

The notes were exchanged between Commander William D. Porter, USN, and Mississippi River captain Marshall J. Miller. Porter had significant naval heritage, as the son of Captain David Porter, brother of Admiral David Dixon Porter, and stepbrother of Admiral David Farragut. At the start of the war Porter took command of the river steamer-turned-casemate ironclad Essex, part of the US Army’s Western Gunboat Flotilla.

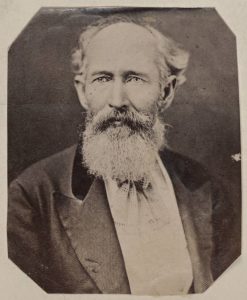

Marsh Miller also came from nautical stock. He learned everything from his father, one of the Mississippi’s first steam captains. When the Civil War began the Memphis-based Miller volunteered to support the Confederacy, arming the sidewheel river steamer Grampus with a pair of 12-pounder Napoleons and a crew of soldiers.

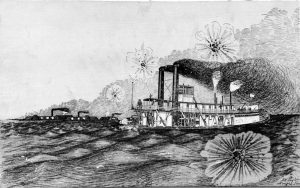

The two captains began their feud because of the January 11, 1862 battle of Lucas Bend. This was the last in a series of skirmishes between November 1861 and January 1862 involving several hastily converted and outfitted warships on both sides that mostly involved one side advancing toward the other, withdrawing once they came under fire from enemy land-based fortifications.

The battle of Lucas Bend was much the same, where Grampus, CSS General Polk, the floating battery New Orleans, and possibly CSS Jackson steamed upriver from Columbus. The Federal ironclads Essex and St. Louis responded. Commander Porter observed one of the Confederate ships sounding “her whistle the moment we were seen” and an artillery exchange commenced, “filling the whole surrounding country with the roar” of gunfire.[1] The Confederate ships soon withdrew, with Porter giving chase all the way to Columbus before his two ironclads also withdrew.

Here the Porter-Miller letters began. Commander Porter and his fellow sailors held a very low opinion of Marsh Miller, calling him “one of the most desperate and at the same time cowardly men in Secesh.”[2] They hated that the lightly-armed Grampus always retreated to the protection of Columbus’ heavy guns instead of fighting it out ship to ship. To challenge Miller to come out and fight, Porter sent downriver “a miniature boat … drifting down” past the floating battery New Orleans with “a mast, from which floated something like a little flag.”[3] On the boat was the first note:

“You damn cowardly rebels, why don’t you come out and show yourselves?

[signed] Com. Porter”[4]

Two days later Captain Miller replied on behalf of the Confederate forces:

“Marine Headquarters

Columbus, KY., Jan. 13, 1862

Commander Porter, on United States Gunboat Essex:

Sir, the iron clad steamer Grampus will meet the Essex at any point and time your Honor may, and show you that the power is in our hands. An early reply will be aggregable to

Your obedient servant, Marsh Miller

Capt. Commanding C.S.I.C. Steamer Grampus.”[5]

Apparently, Porter did not like Miller’s response, and five days later sent another note through the lines:

“United States Gunboat Essex,

Wm. D. Porter, Commanding,

Fort Jefferson, Saturday, Jan 18, 1862.

To the traitor Marsh Miller, commanding a Rebel Gunboat called the Grampus:

Commander Porter has already thrashed your Gunboat Fleet; shelled and silenced your Rebel batteries at the Iron Banks; chased your miserable and cowardly self down behind Columbus; but if you desire to meet the Essex, show yourself any morning in Prentys’ Bend, and you shall then meet with a traitor’s fate – if you have the courage to stand.

God and our Country; ‘Rebels offend both.’

(signed.) Porter”[6]

This is as far as the exchanges, which escalated in temperament with each passing note, are documented. A few days later the military and naval campaigns commenced on the upper Mississippi. Porter’s Essex was heavily involved in the battle of Fort Henry on February 6, receiving a disabling 32-pounder shot that pierced a boiler and scalded 28 men – including Commander Porter himself.

Essex was taken to Cairo, Illinois, to repair damage and so Commander Porter and his sailors could recover. Here is where the newest puzzle piece emerges with another note I just found buried in the National Archives. Apparently, Porter spent the early part of his recovery thinking about Marshall Miller and Grampus, worried he would miss the chance to sink the ship himself. The commander could not resist sending another letter, one which certainly expressed Porter’s growing distaste toward and hatred of the Confederate steamboat captain:

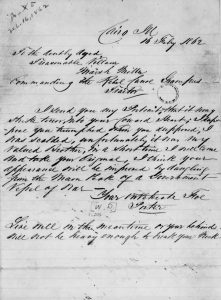

“Cairo, Ill, 16 Feby 1862

To the Roughly Aged, Treasonable Villain Marsh Miller

Commanding the Rebel Canoe Grampus

Traitor

I send you my Portrait; that it may strike terror into your Coward Heart; I suppose you trembled when you supposed I was scalded. Unfortunately it was, my Valued Brother. In a short time I will come and take your Original [Miller’s photograph]. I think your appearance will be improved by dangling from the Main Peak of a Government Vessel of War-

Your Indelecate Foe, Porter

Live well in the meantime or your behind will not be heavy enough to break your neck.”[7]

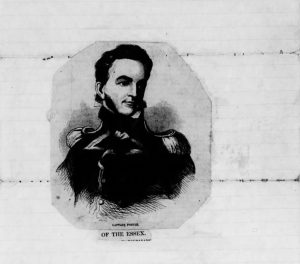

Civil War letters can get pretty crazy, but this seems to beat the rest out. Literally mailing a picture to spark fear in your enemies while simultaneously hoping you could capture him to take his own picture before executing him by hanging for treason takes things to another level. The postscript is particularly telling, where Porter hoped Miller would live extravagantly so he could be fattened up so his neck would snap when he wore a hangman’s noose. Intense does not even describe it. It is worth noting that Porter did not actually send his own image, but that of his father, Captain David Porter, who commanded another USS Essex in the War of 1812.

Despite Commander Porter’s motivation, he and Miller never again met on the river. Porter recovered from his wounds and Essex rejoined the Western Gunboat Flotilla in July 1862 near Vicksburg. In the meantime, Grampus took part in the Island Number Ten campaign. Miller scuttled the improvised steamer when that position fell in April 1862.

Miller survived the war, piloting Mississippi River steamboats into the 1890s. He died in 1906. Commander Porter however did not survive the war. He commanded Essex when it confronted CSS Arkansas at the battle of Baton Rouge in August 1862. After that he was promoted and transferred to New York, where he died on May 1, 1864. Whether Porter took his feud with Marshall Miller to the grave is speculation, but his just recently uncovered letter highlights just how deep rivalries amidst rebellion cut.[8]

Endnotes:

[1] “The Campaign in Kentucky,” New York Times, January 20, 1862; “Western Military Correspondence” New Orleans Daily Crescent, January 16, 1862.

[2] “Capt. Porter on a Whaling Expedition,” New York Times, January 27, 1862.

[3] “Western Military Correspondence” New Orleans Daily Crescent, January 16, 1862.

[4] Ibid; Some papers reported the letter as saying “Come out here you cowardly rebels, and show your gunboats.” See “The Gunboat Challenge on the Mississippi,” New Orleans Daily Delta, February 8, 1862.

[5] “Capt. Porter on a Whaling Expedition,” New York Times, January 27, 1862.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Porter to Miller, February 16, 1862, Area File of the Naval Records Collection, 1775-1910, Confederate Navy – Area 4 and 5, M625, Records Group 45, US National Archives.

[8] “An Old River Pilot Dead,” The Kansas City Times, October 5, 1906; “The Funeral Ceremonies of the Late Commodore Porter,” New York Daily Herald, May 4, 1864.

This was great! hahha

Well, Porter does seem to call Miller “Valued Brother,” anyway.

This was really interesting. I’ll have to look into my family history to see if this Captain Miller was connected to the Miller side of my family. Thanks for the interesting read.