Unpublished: The Pension Files: Unveiling the Humanity of the Civil War Soldier

ECW welcomes back guest author Douglas Ullman, Jr.

As the North reeled from McClellan’s reverse in the Seven Days’ battles in July 1862, the United States Congress signed into a law an act that would have far reaching impacts for both the soldiers and sailors in the armed forces of the United States and the generations of historians and genealogists who remain fascinated with the conflict today. That act, the pension act of July 14, 1862, created a trove of research material which remains one of the best repositories of unpublished primary sources available for students of the Civil War.

In the pension act of July 14, 1862, Congress provided financial benefits to disabled military personnel who had enrolled in the army or navy after March 4, 1861. These benefits expanded and evolved over time to include eligibility for widows of veterans who died of wounds or disease contracted during service, children under the age of 16, and dependent adults such as aging parents who could demonstrate their financial dependency on the service-member son. That the government provided veterans pensions was nothing new; veterans of the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 had also been compensated for their service. However, the sheer scale of the Civil War led to a massive expansion of the pension office. By the war’s end, nearly three million men had served during the war in some capacity. As a result, the annual budget for the pension office grew from roughly $1 million in 1860 to approximately $36 million by 1885.

The resulting mountain of paperwork may have been a headache for the employees of the pension office, but it is a gold mine for historians. Surviving veterans had to submit documentation of their wounds or disabilities in the form of standardized medical examination forms. These returns describe the nature of wounds, often with diagrams illustrating the location of the wound with entrance and exit points. Further documentation describes in detail the long-term effects of hard campaigning on veterans of the war. As veterans aged, many of them applied for increases in their pension. Each additional application required additional exams and forms, thus providing us a window not only into the nature of a soldier’s initial wound, but also into how that individual recovered (or didn’t) from their wartime ailment. As a result, a single veteran who survived the war might submit multiple applications over the rest of his lifetime, allowing us the opportunity to track the long-term repercussions of fighting for the Union.

In addition to medical forms, applicants—particularly widows and dependent parents—often had to prove their financial dependency. As a result, pension files often contain soldier letters, revealing the human side of the conflict that is not usually found in the Official Records. Consider the case of Michael Walsh of the 102nd New York, whose pension file contains several letters from his time in service. Walsh’s letters detail the frustrations of being without pay, the scarcity of stamps, and the uncertainty felt by the soldier in the ranks. Two letters, dated August 14 and 16, 1862, are of particular interest. In them, Michael gives his wife an unvarnished account of his regiment’s baptism by fire at the battle of Cedar Mountain, in which “Every man Faut Like tigers.” But more than that, Michael’s letters reveal something of who he was as a man and a husband.

In the first place, we learn that Michael was an atrocious speller with only a casual relationship with punctuation. In this phonetic style we can even get a sense of how he spoke. For example, when writing the word “through,” the h is often dropped, implying that Michael (like a real New Yorker) said “troo” when he meant “through.” This may not seem like a major discovery—it certainly doesn’t unravel any salient issue of military strategy or historical memory—but it helps us see the man inside the uniform.

In writing to his wife, Johana, Michael often called her “Josey,” a name not printed on any official document, but clearly a part of their everyday life. We see that he wrestled with the consequences of his being away from home and with what it meant to be a provider and caretaker at so long a distance when he writes letters such as: “Dear Wife its a Hard Feeling For me to think that you have to Live out For a Living all t[h]rough my Faulth.” Several times he asked Josey to move in with her brother, both for her well-being in the event something should happen to him and, perhaps, even as a means to save money. It’s one thing to know that soldiers went without pay for long periods of time; it’s another to see how these hardships affected a marriage.

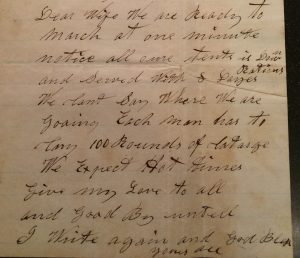

In this way, Walsh’s pension file exposes how he struggled with his role as both soldier and husband, these letters unveil his humanity. On April 14, 1863, Michael wrote to Josey that the 102nd New York was “ready to march at one minute notice.” The tents had been taken down, the men issued three days rations and 100 rounds of ammunition. “We Expect Hot times,” he wrote. “Give my Love to all and Good By untell I Write again.” That may very well have been the last letter Michael Walsh ever wrote his wife. He was mortally wounded on May 3, 1863, at the Battle of Chancellorsville.

Pension files also serve as a stark reminder that the war touched many lives not only beyond the battlefield but for many years after. This is painfully apparent in the pension records of Henry Elberson of the 11th New Jersey. He and Elizabeth Elberson had been married less than four years when he mustered in on August 15, 1862. The couple had two children together, William, born 1859, and Hope, born 1861. In March of 1863, Elizabeth gave birth to a third child, Elmer. It’s unlikely Henry had the opportunity to meet his youngest child. When the 11th New Jersey suffered severe losses in its stand at Gettysburg’s Klingel Farm on July 2, 1863, Henry was mortally wounded and died three days later. Unfortunately, Henry’s death was only the beginning of the Elbersons’ grief. Young Elmer died three months shy of his second birthday. His bereaved mother was apparently in very poor health and “had been for some time an invalid” in the Burlington County Poor House, when she died on March 17, 1865.

Pension files also serve as a stark reminder that the war touched many lives not only beyond the battlefield but for many years after. This is painfully apparent in the pension records of Henry Elberson of the 11th New Jersey. He and Elizabeth Elberson had been married less than four years when he mustered in on August 15, 1862. The couple had two children together, William, born 1859, and Hope, born 1861. In March of 1863, Elizabeth gave birth to a third child, Elmer. It’s unlikely Henry had the opportunity to meet his youngest child. When the 11th New Jersey suffered severe losses in its stand at Gettysburg’s Klingel Farm on July 2, 1863, Henry was mortally wounded and died three days later. Unfortunately, Henry’s death was only the beginning of the Elbersons’ grief. Young Elmer died three months shy of his second birthday. His bereaved mother was apparently in very poor health and “had been for some time an invalid” in the Burlington County Poor House, when she died on March 17, 1865.

While it is impossible to definitively connect Elizabeth’s death to the battlefield, one can’t help but wonder to what extent her health was impacted by having to fend for herself. Her death made William and Hope orphans before the ages of five and three. They were left in the care of one A.J. Allen, whose connection to the family is unclear. But, whoever he was, Allen completed the application for an orphans’ pension for the surviving Elberson children, who received the money owed to them by the government. By the time William and Hope had aged out of their pension benefit, they had lived more than two-thirds of their lives without either parent. Henry Elberson is buried in the Soldiers’ National Cemetery in Gettysburg, where his simple stone grave marker points not only to a life lost in defense of the Union but to the lives whose trajectories were forever altered by his sacrifice.

We often remember soldiers on battlefields. And, while we try to do otherwise, it is easy to let the individual soldiers disappear into blocks of blue and red moving across the landscape. The pension records defy that impulse. In reading the pension files we learn about marriages torn asunder by distance, families destroyed by war, and bodies whose youth and vigor were forever marred by the trials of hard campaigning and exposure to the elements. Other primary sources may offer some of this information for one man or a small set of Civil War participants, but few can offer so much information for so many in one single location.

The possibilities for research are so varied and rich that the pension files ought not to be overlooked by students of the war. Fortunately, much of this material is available online at Fold3.com. While it costs nothing to create an account, the ability to view and download documents is restricted to paying members. (A basic subscription is currently $7.95/month) This is a great option for those who wish to access the widows’ pension files digitized by the National Archives from the comfort of their home. One can also view pension records in person by visiting the National Archives in Washington, DC. However, researchers can only pull four records at a time and records are only pulled at certain times of the day. Be sure to plan ahead and visit nara.gov for the most up-to-date information. No matter how one accesses this treasure trove of primary sources, the pension files have something for everyone, regardless of their area of interest or focus.

Doug Ullman, Jr. has written numerous pieces for America Battlefield Trust and frequently contributed to their Civil War in4 and War Department series. He is a graduate of New York University’s Steinhardt School.

Excellent!

You nailed the value of discovering these letters with the statement, “… it certainly doesn’t unravel any salient issue of military strategy or historical memory—but it helps us see the man inside the uniform.” How true.

A bit of caution regarding Fold3. Where available, the information on Fold3 is quite helpful. However, I found some files a bit skimpy and navigating the site also has its frustrations – particularly with the promotions to add Ancestry for additional information.

Thanks for bringing to life stories of the soldiers and their families.

Pension files from the National Archives ($75) were a good source of information for substantiating the events of my 82d Ohio Civil War ancestor and for telling his story google Hiram’s Honor