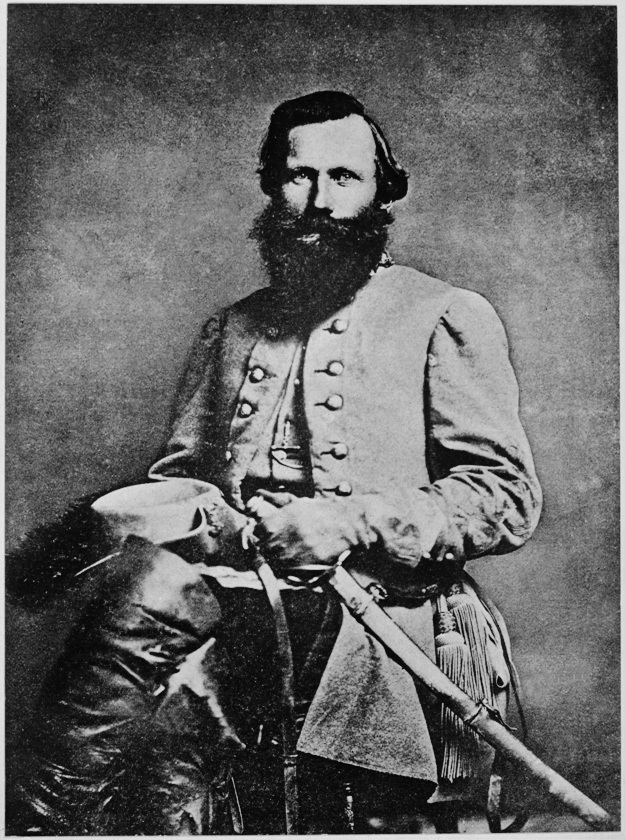

Stuart’s Big Capture and the Cost of Doing Business

Jeb Stuart, cut off from the Army of Northern Virginia’s infantry during the last days of June 1863, later tried to excuse his position by making much ado about his exploits. In particular, he crowed about a Federal wagon train his men captured on June 28 in Rockville, Maryland. The capture of such a wagon train was usually worth celebrating for the resource-hungry ANV, and Stuart’s report—written to help cover his own butt—self-servingly inflates the importance of the capture.

But the Federal reaction to that capture is fascinating to me.

Soon after taking possession of Rockville, Stuart reported, “a long train of wagons approached from the direction of Washington, apparently but slightly guarded.”[1] In his estimation, the train stretched eight miles long, with its tail end being only three or four miles from Washington.

Someone from the wagon train noticed the Confederate horsemen and raised the alarm. “[T]hey attempted to turn the wagons, and at full speed to escape . . .” Stuart said. “Not one escaped, though many were set and broken, so as to require their being burned.” The net gain for Stuart were 125 of the “best United States model wagons and splendid teams,” which were “secured and driven off” along with the mules and harnesses of the broken wagons.[2]

The captured wagons ultimately slowed Stuart even further in his attempt to reunite with Lee. The movie Gettysburg famously imagines the eventual meeting between Stuart and Lee on the evening of July 2, with Stuart proudly presenting his booty and Lee admonishing him for letting that booty turn into a hindrance.

We don’t know what words really passed between the men during that exchange, but in his official report, written August, Stuart very much tried to play up the significance of his foray:

This move of my command between the enemy’s seat of government and the army charged with its defense involved serious loss to the enemy and material (over 1,000 prisoners having been captured), and spread terror and consternation to the very gates of the capital. . . .

Sincere or exaggerated, Stuart placed far more importance on the episode than the Federal army did. Brig. Gen. Montgomery C. Miegs, quartermaster general of the army, fired off an annoyed dispatch to Brig. Gen. Rufus Ingalls, quartermaster for the Army of the Potomac. The AoP was supposed to be recipient of the supplies Stuart captured. “Last fall I gave orders to prevent the sending of wagon trains from this place to Frederick without escort,” Miegs wrote from D.C. “The situation repeats itself, and gross carelessness and inattention to military rule has this morning cost us 150 wagons and 900 mules, captured by cavalry between this and Rockville.”[3]

The army was “now insulted by burning wagons” three miles outside of the national capital, and to add injury, all of Ingalls communications were in Confederate hands.

What was a major coup to Stuart was, at worse, an annoying insult to Miegs.

But even more interesting was the reaction of newly appointed AoP commander Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade. He had more pressing matters on his mind. “My main point being to find and fight the enemy, I shall have to submit to the cavalry raid around me I some measure.”[4]

In other words, to Meade, raids like Stuart’s were just the cost of doing business.

Think about that for a moment: Federal forces existed in such a state of perpetual plenty that Meade could shrug off the loss of 150 wagons and 900 mules (not to mention the 1,000 prisoners Stuart claimed for the raid). That’s not to say the AoP was wallowing in unlimited supplies—in fact, one of Meade’s top concerns on Day One in command was trying to get his men resupplied. Shoes were in particularly short supply.[5]

This illustrates in a nutshell one of Lee’s main reasons for striking north. Federals had more of everything, and the longer the war dragged out, the less the South would have even as the North would continue to exert the pressure of plenty.

————

————

[1] Stuart, OR XXVII, pt. 2, 694.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Miegs to Ingalls, 28 June 1863, O.R. XXVII, pt. 3, 378.

[4] Meade to Halleck, 29 June 1863, O.R. XXVII, pt. 1, 67.

[5] Ironic that the story of Gettysburg so often brings up the myth of a Confederate shoe shortage when, in fact, the Federals were the ones in serious need of them. On June 28, Meigs sent the army 20,000 pairs of boots, with socks to go with them.

Wow!

Lee advanced into Pennsylvania blind and deaf. And I will admit, he mis-used the cavalry he had with him.

I rarely agree with my NY friend ( I’m from Jersey, it’s in the blood) but he nailed it.

Great essay … Stuart was no dummy … so, it’s not surprising that, for the record, he played up the “look at all the wagons i captured and havoc i caused’ angle … and once he find the ANV, it’s likely he knew he was in hot water with the boss — losing contact with the ANV main body for days in enemy territory, not moving quickly because he was dragging captured wagons, and providing zero intel to Lee … to make matters worse, the cavalry brigades he left with the ANV — Jones’ and Robertson’s — were neither his best troopers or his best brigade commanders.